Harvard Polo Asia by Abigail Trafford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians

138th IPU ASSEMBLY AND RELATED MEETINGS Geneva, 24 – 28.03.2018 Governing Council CL/202/11(b)-R.2 Item 11(b) Geneva, 28 March 2018 Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians Report on the mission to Mongolia 11 - 13 September 2017 MNG01 - Zorig Sanjasuuren Table of contents A. Origin and conduct of the mission ................................................................ 4 B. Outline of the case and the IPU follow up action ........................................... 5 C. Information gathered during the mission ...................................................... 7 D. Findings and recommendations further to the mission ................................ 15 E. Recent developments ................................................................................... 16 F. Observations provided by the authorities ..................................................... 17 G. Observations provided the complainant ....................................................... 26 H. Open letter of one of the persons sentenced for the murder of Zorig, recently published in the Mongolian media ................................................................ 27 * * * #IPU138 Mongolia © Zorig Foundation Executive Summary From 11 to 13 September 2017, a delegation of the Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians (hereinafter “the Committee”) conducted a mission to Mongolia to obtain further information on the recently concluded judicial proceedings that led to the final conviction of the three accused for the 1998 assassination of Mr. Zorig -

Population Genetic Analysis of the Estonian Native Horse Suggests Diverse and Distinct Genetics, Ancient Origin and Contribution from Unique Patrilines

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Population Genetic Analysis of the Estonian Native Horse Suggests Diverse and Distinct Genetics, Ancient Origin and Contribution from Unique Patrilines Caitlin Castaneda 1 , Rytis Juras 1, Anas Khanshour 2, Ingrid Randlaht 3, Barbara Wallner 4, Doris Rigler 4, Gabriella Lindgren 5,6 , Terje Raudsepp 1,* and E. Gus Cothran 1,* 1 College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 2 Sarah M. and Charles E. Seay Center for Musculoskeletal Research, Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children, Dallas, TX 75219, USA 3 Estonian Native Horse Conservation Society, 93814 Kuressaare, Saaremaa, Estonia 4 Institute of Animal Breeding and Genetics, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria 5 Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 75007 Uppsala, Sweden 6 Livestock Genetics, Department of Biosystems, KU Leuven, B-3001 Leuven, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected] (T.R.); [email protected] (E.G.C.) Received: 9 August 2019; Accepted: 13 August 2019; Published: 20 August 2019 Abstract: The Estonian Native Horse (ENH) is a medium-size pony found mainly in the western islands of Estonia and is well-adapted to the harsh northern climate and poor pastures. The ancestry of the ENH is debated, including alleged claims about direct descendance from the extinct Tarpan. Here we conducted a detailed analysis of the genetic makeup and relationships of the ENH based on the genotypes of 15 autosomal short tandem repeats (STRs), 18 Y chromosomal single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), mitochondrial D-loop sequence and lateral gait allele in DMRT3. -

2021 Illinois Racing and Stakes Guide

State of Illinois JB Pritzker, Governor Department of Agriculture Jerry Costello II, Acting Director 2021 Illinois Racing and Stakes Guide RACING SCHEDULES PARI-MUTUELS STATE FAIRS COUNTY FAIRS COLT ASSOCIATIONS Illinois Department of Agriculture Horse Racing Programs P. O. Box 19281 - Illinois State Fairgrounds Springfield, IL 62794-9281 (217) 782-4231 - Fax (217) 524-6194 - TTY (866) 287-2999 This guide has been developed as a courtesy by the Illinois Department of Agriculture. It may contain errors or omissions and, therefore, may not be raised in opposition to the schedule of Illinois racetracks. Please request a Stakes Booklet from the racetrack or confer with individual fair management as the only authority. The Illinois Department of Agriculture requires that all Standardbred foals be duly certified with the Bureau of Horse Racing to participate in the Illinois Standardbred Breeders Fund program. A certificate is issued to the owner of the foal at the time of Illinois registration and is passed on from owner to owner; this certificate must be transferred into the new owner’s name as soon as possible after purchase. For further information on the Illinois Conceived and Foaled (ICF) program, contact: Illinois Department of Agriculture P. O. Box 19281 Illinois State Fairgrounds Springfield, Illinois 62794-9281 Phone: (217)782-4231 FAX: (217)524-6194 TTY: (217)524-6858 ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE 2021 ILLINOIS RACING AND STAKES GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PARI-MUTUEL RACING Page ICF PARI-MUTUEL RACING SCHEDULES Hawthorne Race Track ..................................................................................................... 2 Illinois State Fair................................................................................................................. 5 Du Quoin State Fair ........................................................................................................... 8 STAKE PAYMENT SCHEDULES Hawthorne Night of Champions ................................................................................... -

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

Naadam Festival Both in Ulaanbaatar and Karakorum Mongolia Special Tour (July 5-July 13)

Naadam Festival Both in Ulaanbaatar and Karakorum Mongolia Special Tour (July 5-July 13) Key Information: Trip Length: 9 days/8 nights. Trip Type: Easy to Moderate. Tour Code: SMT-NF-9D Specialty Categories: Adventure Expedition, Cultural Event Journey, Local Culture, Nature & Wildlife, and Sports. Meeting/Departure Points: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (excluding flights). Land Nadaam Festival Group Size: 2-9 adults or more participants. Free Tour: If you have 16 persons (15 paying persons + 1 free, based on twin standard room: 8). Whenever you sign up a group of 16 people or more to Samar Magic Tours, you will enjoy a free trip to yourself, travelling as the group leader with the group. Excluding the flights, and the single room at hotels. Hot Season in Mongolia: July 5th - July 13th! Total Distance: about + 1500kms/932miles. Airfare Included: No. Tour Customizable: Yes Book by December 15th and save: 100 USD or 85 €! Tour Highlights: Upon your arrival in Ulaanbaatar, meet Samar Magic Tours team. Naadam is a traditional type of Festival in Mongolia. The festival is also locally termed 'the three games of men'. The games are Mongolian wrestling, horse racing and archery and are held throughout the country. The three games of wrestling, horse racing, and archery had been recorded in the 13rd century book The Secret History of the Mongols. It formally commemorates the 1921 Revolution, when Mongolia declared itself independent of China. Women have started participating in the archery and girls in the horse-racing games, but not in Mongolian wrestling. The biggest festival is held in the Mongolian capital Ulaanbaatar, during the National Holiday from July 11th - July 13th, in the National Sports Stadium. -

Horse Racing

Horse Racing From the publisher of: EQUUS Dressage Today Horse & Rider Practical Horseman Arabian Horse World Search Home :: Classifieds :: Shopping :: Forums/Chat :: Subscribe :: News & Results :: Giveaway Winners Newsletter Sign-Up Racing Win It! Weekly tips and articles Sponsor this topic! Win Reichert on horse care, training Celebration VIP Passes! and more >> Speed is of the essence in this sport that pits the fastest equines against each Growing Up With Horses other. Here, find stories on Thoroughbreds, Standardbreds and other racing Kids' Essay Contest TOPICS breeds. Enter JPC Equestrian's Home $10,000 Giveaway On the 30th Anniversary of About EquiSearch Win an Irish Riding Trip Art & Graphics Ruffian's Last Race & More! Associations Lyn Lifshin reflects on the life of the super racehorse Ruffian who died Breeds during a match race against Foolish Where To Shop! Horse Care Pleasure on July 6, 1975. Columnists Equestrian Collections Community The Superstore for Horse Equine Education and Rider EquiWire News/Results The Equine Collection Farm and Stable Horse books and DVDs Kentucky Horse Park Glossary Horsey Humor Horse Racing News & Results Gift Shop Junior Horse Lovers Gifts and Collectibles Find A Tack Shop Lifestyle More Racing Articles Magazines Shoemaker Remembered Beginning Adult Rider Buyers' Guides October 16, 2003 -- Bill Shoemaker died October 12 at Quiz the age of 72. His fellow jockeys share their memories. Insurance Rescue/Welfare Tack & Apparel Seabiscuit Trailers Shopping More Buyers' Guides Horse Sports Endurance Seabiscuit: An American Legend. Steeplechase News, photos, quotes and more on the Depression-era racing star and his Olympics connections. To visit EquiSearch's special section on Seabiscuit click here. -

OLYMPIA SPORTING HOUSE 1, Nirmal Chandra Street, Bowbazar, Calcutta – 700 012 Phone: 033- 2212-2366 (O) & 2212-0311 (O), 2433-8384 (Resi

OLYMPIA SPORTING HOUSE 1, Nirmal Chandra Street, Bowbazar, Calcutta – 700 012 Phone: 033- 2212-2366 (O) & 2212-0311 (O), 2433-8384 (Resi. on Emergency Only) Email : [email protected] & [email protected] Website: www.olympiasportinghouse.com & www.olympiakolkata.com CST No. 19530975221, VAT. No. 19530975027 IEC No. 0207026441 Bankers :Canara Bank, ( CNRB 0000152 )Bowbazar Br., Kolkata-12. A/C No. 0152201010213 (Olympia Established in 1896, the Starting Year of Modern Olympics in Athens ) SECTION - G ANIMAL SPORTS SECTION UNIT 1 HORSE POLO, HORSE RIDING , EQUESTRIAN &HORSE RACING O001 HORSE POLO STICK ( MALLET ) Step-1 : Practice Quality , Assam Cane, Size 51” , 48”, 45” PRICE , 42” ASK FOR O002 HORSE POLO STICK Step-2 : Professional Quality, Ridden ( Manau ) Cane, Rubber Wrapped Grip With Cotton / Leather Thong ( Thumb Sling ), Cedar Wood or Bamboo Head ( Cigar ) of 9”- 9 ½” Length & 160 to 240 gm Weight , Size 54” to 45”, Cigar is Color or Polish as per Demand With a Carry Bag O003 HORSE POLO STICK Step-3 : Export Quality, Ridden Cane, Fiber Film Wrapping Super Mallet & Cigar for Long Life , Size 54” to 45”, With Carry Bag O004 POLO STICK HEAD : Made With Imported Resinous CEDAR Wood. 9” Length O005 POLO MALLET FOOT CIGAR: Different Sizes & Diameter . As per Demand, 9” – 10” , Export Qul. O006 HORSE POLO BALL ( OUT DOOR ) Step-1 : Made With Bamboo Root or Wood , 3 ¼”-3 ½” Diameter O007 HORSE POLO BALL Step -2 : Bamboo Root or Willow / Pine Root , 8.3 cm ( 3 ¼” ) Dia Wt.100-115g O108 POLO BALL WOODEN FIBER LAMINATED : Made in Calcutta ,Wooden Core, Polyester Laminated, Practice O109 HORSE POLO GOAL POST : Set of 4 No. -

Golden Eagle Luxury Trains VOYAGES of a LIFETIME by PRIVATE TRAIN TM

golden eagle luxury trains VOYAGES OF A LIFETIME BY PRIVATE TRAIN TM trans-mongolian express golden eagle trans-mongolian express featuring the naadam festival moscow - kazan - yekaterinburg - novosibirsk - irkutsk lake baikal - ulan ude - ulaan baatar For a fuller insight into Mongolia, why not experience our Naadam Festival Trans-Mongolian departure in July - a journey across Russia onboard the Golden Eagle combined with a visit to the Mongolian national festival. Naadam is the one and only Big Event in Mongolia - a spectacularly colourful national festival, held every year. Naadam literally means ‘three manly games’. Known as the world’s second oldest Olympics, it celebrates what defined civilisation in the Steppes eight centuries ago: archery, wrestling and horse riding. For a preview of the festival, our new video is available to view on our website: www.goldeneagleluxurytrains.com www.goldeneagleluxurytrains.com To Book Call +44 (0)161 928 9410 or Call Your Travel Agent golden eagle trans-mongolian express what’s included moscow Kazan RUSSIA Yekaterinburg Novosibirsk CASPIAN SEA Lake Baikal KAZAKHSTAN Irkutsk Ulan Ude ulaan baatar MONGOLIA CHINA IRAN JAPAN finest rail off-train excursions golden eagle tour schedules daily tour itineraries accommodation programme difference EASTBOUND 2015 WESTBOUND 2015 EASTBOUND WESTBOUND Private en-suite accommodation Full guided off-train excursions programme Experienced Tour Manager July 1 – July 13 July 10 – July 22 Day 1 Arrive Ulaan Baatar Day 1 Arrive Moscow 24-hour cabin attendant service -

Supplement 1999-11.Pdf

Ìàòåðèàëû VI Ìåæäóíàðîäíîãî ñèìïîçèóìà, Êèåâ-Àñêàíèÿ Íîâà, 1999 ã. 7 UDC 591 POSSIBLE USE OF PRZEWALSKI HORSE IN RESTORATION AND MANAGEMENT OF AN ECOSYSTEM OF UKRAINIAN STEPPE – A POTENTIAL PROGRAM UNDER LARGE HERBIVORE INITIATIVE WWF EUROPE Akimov I.1, Kozak I.2, Perzanowski K.3 1Institute of Zoology, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 2Institute of the Ecology of the Carpathians, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 3International Centre of Ecology, Polish Academy of Sciences Âîçìîæíîå èñïîëüçîâàíèå ëîøàäè Ïðæåâàëüñêîãî â âîññòàíîâëåíèè è â óïðàâëåíèè ýêîñèñòåìîé óê- ðàèíñêèõ ñòåïåé êàê ïîòåíöèàëüíàÿ ïðîãðàììà â èíèöèàòèâå WWE Åâðîïà “êðóïíûå òðàâîÿäíûå”. Àêèìîâ È., Êîçàê È., Ïåðæàíîâñêèé Ê. –  ñâÿçè ñ êëþ÷åâîé ðîëüþ âèäîâ êðóïíûõ òðàâîÿäíûõ æèâîòíûõ â ãàðìîíèçàöèè ýêîñèñòåì ïðåäëàãàåòñÿ øèðå èñïîëüçîâàòü åäèíñòâåííûé âèä äèêîé ëîøàäè — ëîøàäü Ïðæåâàëüñêîãî – â ïðîãðàìíîé èíèöèàòèâå Âñåìèðíîãî ôîíäà äèêîé ïðèðîäû â Åâðîïå (LHF WWF). Êîíöåïöèÿ èñïîëüçîâàíèÿ ýòîãî âèäà êàê èíñòðóìåíòà âîññòàíîâëåíèÿ è óïðàâëåíèÿ â ñòåïíûõ ýêîñèñòåìàõ â Óêðàèíå õîðîøî ñîîòâåòñòâóåò îñíîâíîé íàïðàâëåííîñòè LHJ WWF: à) ñîõðàíåíèè ëàíäøàôòîâ è ýêîñèñòåì êàê ìåñò îáèòàíèÿ êðóïíûõ òðàâîÿäíûõ á) ñî- õðàíåíèå âñåõ êðóïíûõ òðàâîÿäíûõ â âèäå æèçíåñïðîñîáíûõ è øèðîêîðàñïðîñòðàíåííûõ ïîïóëÿ- öèé â) ðàñïðîñòðàíåíèå çíàíèé î êðóïíûõ òðàâîÿäíûõ ñ öåëüþ óñèëåíèÿ áëàãîïðèÿòíîãî îòíîøå- íèÿ ê íèì ñî ñòîðîíû íàñåëåíèÿ. Íàìå÷åíû òåððèòîðèè ïîòåíöèàëüíî ïðèãîäíûå äëÿ èíòðîäóê- öèè ýòîãî âèäà. The large part of Eurasia is undergoing now considerable economic and land use changes, which brings a threat to some endangered populations or even species, but on the other hand creates new opportunities for ecological restoration of former wilderness areas. Large herbivores are key species for numerous ecosystems being the link between producers (vegetation), and secondary consumers (predators), including people. -

Horse Race Or Steeplechase a Board Game That People of All Ages Have

Horse Race or Steeplechase A board game that people of all ages have enjoyed for many years is Steeplechase or “Horse Race.” The name Steeplechase came from the real horse races run in Europe where the cross-country race course went over many natural and man- made obstacles, such as fences, stone walls, and water-filled ditches. The rider’s goal at the end of the race was near a church with a steeple that could be seen from miles away. Game boards for Steeplechase can be found in European museums. The Old Steeplechase Game Board Walter Kuse Had as a Child Walter Kuse had a printed horse race game board when he was a small boy, but that game was worn out and broken by younger children. Walter remembered the fun he had with the game as a child and also the exciting horse races that were held then at the Taylor County Fair. New Horse Race Game Board Walter Kuse painted this game board in the 1930’s. He painted it on the back of recycled advertising cardboard for his daughter Hildegard. The family and visitors had fun playing it and remembering stories about horses they had known. Game Rules Use buttons or other markers. Throw a die to see how many spaces to move. Toss the die to tell who will go first. The person with the lowest number begins. Take turns in a clockwise direction. Follow the directions if any are written on the space where you land. If you stop on a rail fence or a stone fence, you must toss a six to get off. -

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

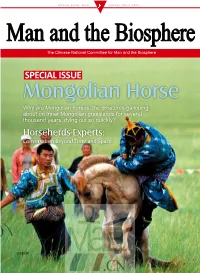

Mongolian Horse Why Are Mongolian Horses, the Creatures Galloping About on Inner Mongolian Grasslands for Several Thousand Years, Dying out So Quickly?

SPECIAL ISSUE 2010 SPECIAL ISSUE 2010 Man and the Biosphere Man and the Biosphere The Chinese National Committee for Man and the Biosphere SPECIAL ISSUE Mongolian Horse Why are Mongolian horses, the creatures galloping about on Inner Mongolian grasslands for several thousand years, dying out so quickly? Horseherds-Experts: Conversation Beyond Time and Space A home on the grassland. Photo: Ayin SPECIAL SPECIAL ISSUE 2010 Postal Distribution Code:82-253 Issue No.:ISSN 1009-1661 CN11-4408/Q US$5.00 The Silingol Grassland. Photo: He Ping Photo: The Silingol Grassland. This oil painting dates from 1986. The boy is called Chog and he is about 14 or 15 years old. This is about the time when livestock were starting to be distributed among individual households, just before the privatization of pasturelands. Now, 20 years later, the situation on the grasslands is very worrying. Desertification is largely caused by over-development and over-grazing. In the old days, the traditional nomadic way of life did no harm to the grasslands, now it has been replaced with privatized farms, the grassland is degenerating. Text and photo: Chen Jiqun (an artist specializing in oil painting and depicting grassland scenes. He lived in Juun Ujumucin, Silin ghol aimag (league), for 13 years from 1967) The Mongolian Horse – Taking us on a Long Journey Our editing team There are, perhaps, only a few animals in the world that are as deeply embedded into a culture as is the Mongolian Horse. This is an animal whose fate is so closely tied to a people that its situation is an indicator of both the health of the external environment and the culture upon which it relies.