The Mongolian Horse and Horseman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Genetic Analysis of the Estonian Native Horse Suggests Diverse and Distinct Genetics, Ancient Origin and Contribution from Unique Patrilines

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Population Genetic Analysis of the Estonian Native Horse Suggests Diverse and Distinct Genetics, Ancient Origin and Contribution from Unique Patrilines Caitlin Castaneda 1 , Rytis Juras 1, Anas Khanshour 2, Ingrid Randlaht 3, Barbara Wallner 4, Doris Rigler 4, Gabriella Lindgren 5,6 , Terje Raudsepp 1,* and E. Gus Cothran 1,* 1 College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 2 Sarah M. and Charles E. Seay Center for Musculoskeletal Research, Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children, Dallas, TX 75219, USA 3 Estonian Native Horse Conservation Society, 93814 Kuressaare, Saaremaa, Estonia 4 Institute of Animal Breeding and Genetics, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria 5 Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 75007 Uppsala, Sweden 6 Livestock Genetics, Department of Biosystems, KU Leuven, B-3001 Leuven, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected] (T.R.); [email protected] (E.G.C.) Received: 9 August 2019; Accepted: 13 August 2019; Published: 20 August 2019 Abstract: The Estonian Native Horse (ENH) is a medium-size pony found mainly in the western islands of Estonia and is well-adapted to the harsh northern climate and poor pastures. The ancestry of the ENH is debated, including alleged claims about direct descendance from the extinct Tarpan. Here we conducted a detailed analysis of the genetic makeup and relationships of the ENH based on the genotypes of 15 autosomal short tandem repeats (STRs), 18 Y chromosomal single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), mitochondrial D-loop sequence and lateral gait allele in DMRT3. -

Harvard Polo Asia by Abigail Trafford

Horsing Around IN THE HIGHWAYS AND BYWAYS OF POLO IN ASIA We all meet up during the six-hour stopover in the Beijing Airport. The invitation comes from the Genghis Khan Polo Club to play in Mongolia and then to head back to China for a university tournament at the Metropolitan Polo Club in Tianjin. Say, what? Yes, polo! Both countries are resurrecting the ancient sport—a tale of two cultures—and the Harvard players are to be emissaries to help generate a new ballgame in Asia. In a cavernous airport restaurant, I survey the Harvard Polo Team: Jane is captain of the women’s team; Shawn, captain of the men’s team; George, the quiet one, is a physicist; Danielle, a senior is a German major; Sarah, a biology major; Aemilia writes for the Harvard Crimson. Marina, a mathematician, will join us later. Neil and Johann are incoming freshmen; Merrall, still in high school, is a protégé of the actor Tommy Lee Jones—the godfather of Harvard polo. And where are the grownups? Moon Lai, a friend of Neil’s parents, is the photographer from Minnesota. Crocker Snow, Harvard alum and head of the Edward R. Murrow Center at Tufts, is tour director and coach. I am along as cheer leader and chronicler. We stagger onto the late-night plane to Ulan Bator (UB), the capital of Mongolia, pile into a van and drive into the darkness—always in the constant traffic of trucks. Our first camp of log cabins is near an official site of Naadam—Mongolia’s traditional summer festival of horse racing, wrestling and archery. -

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

Division F – Jr. Fair Equine

EFFECTIVE JAN. 1, 2019 Junior Fair Rules, Regulations, and Livestock Sections Division F – Jr. Fair Equine Key Leader: Samantha Seidenstricker Senior Fair Board: Junior Fair Board: Dates: Mandatory Equine Meeting* Saturday July 10, 2021 12:00pm English Classes Monday July 12, 2021 10am Western Riding & Contesting Classes Tuesday July 13, 202110am Donkey Show (First Half) Wednesday July 14, 2021 10pm Horse/Donkey Freestyle Riding** Wednesday July 14, 2021 5pm Donkey Show (Second Half) Thursday July 15, 2021 10am Trail Classes Thursday July 15, 2021 following Donkey Show Dressage Event Friday July 16, 2021 10am Versatility Friday, July 16, 2021 following Dressage Equine Fun Show*** Saturday July 17, 2021 10am *Equine meeting will be held at the Horse Area Announcer Stand. Exhibitor and one parent/guardian are required to sign-in. Club assignments will be handed out at that time. **Registration and Music CD is due to Key Leader by Saturday July 6, 2019. Songs can be no more than 3 minutes in length and cannot contain any explicit language or innuendo. Complete rules are available at the extension office. Divisions: Monday 10am English Classes 601Easy-Gaited/Standardbred Showmanship E/W Horse/Pony 14-18▼ 602 Easy-Gaited/Standardbred Showmanship – E/W Horse/Pony 8-13 ▼ 603 Saddleseat Showmanship – Horse/Pony 14- 18 ● 604 Saddleseat Showmanship– Horse/Pony 8-13 ● 605 Saddleseat Showmanship – Horse/Pony W/T 606 Saddle Type Halter - Horse/Pony 14-18 ● 609 Saddle Type Halter - Horse/Pony 8-13 ● 610 Hunter In Hand Showmanship – Horse/Pony 14-18 ■ 611 Hunter In Hand Showmanship – Horse/Pony 8-13 ■ MADISON COUNTY FAIR 42 EFFECTIVE JAN. -

Supplement 1999-11.Pdf

Ìàòåðèàëû VI Ìåæäóíàðîäíîãî ñèìïîçèóìà, Êèåâ-Àñêàíèÿ Íîâà, 1999 ã. 7 UDC 591 POSSIBLE USE OF PRZEWALSKI HORSE IN RESTORATION AND MANAGEMENT OF AN ECOSYSTEM OF UKRAINIAN STEPPE – A POTENTIAL PROGRAM UNDER LARGE HERBIVORE INITIATIVE WWF EUROPE Akimov I.1, Kozak I.2, Perzanowski K.3 1Institute of Zoology, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 2Institute of the Ecology of the Carpathians, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 3International Centre of Ecology, Polish Academy of Sciences Âîçìîæíîå èñïîëüçîâàíèå ëîøàäè Ïðæåâàëüñêîãî â âîññòàíîâëåíèè è â óïðàâëåíèè ýêîñèñòåìîé óê- ðàèíñêèõ ñòåïåé êàê ïîòåíöèàëüíàÿ ïðîãðàììà â èíèöèàòèâå WWE Åâðîïà “êðóïíûå òðàâîÿäíûå”. Àêèìîâ È., Êîçàê È., Ïåðæàíîâñêèé Ê. –  ñâÿçè ñ êëþ÷åâîé ðîëüþ âèäîâ êðóïíûõ òðàâîÿäíûõ æèâîòíûõ â ãàðìîíèçàöèè ýêîñèñòåì ïðåäëàãàåòñÿ øèðå èñïîëüçîâàòü åäèíñòâåííûé âèä äèêîé ëîøàäè — ëîøàäü Ïðæåâàëüñêîãî – â ïðîãðàìíîé èíèöèàòèâå Âñåìèðíîãî ôîíäà äèêîé ïðèðîäû â Åâðîïå (LHF WWF). Êîíöåïöèÿ èñïîëüçîâàíèÿ ýòîãî âèäà êàê èíñòðóìåíòà âîññòàíîâëåíèÿ è óïðàâëåíèÿ â ñòåïíûõ ýêîñèñòåìàõ â Óêðàèíå õîðîøî ñîîòâåòñòâóåò îñíîâíîé íàïðàâëåííîñòè LHJ WWF: à) ñîõðàíåíèè ëàíäøàôòîâ è ýêîñèñòåì êàê ìåñò îáèòàíèÿ êðóïíûõ òðàâîÿäíûõ á) ñî- õðàíåíèå âñåõ êðóïíûõ òðàâîÿäíûõ â âèäå æèçíåñïðîñîáíûõ è øèðîêîðàñïðîñòðàíåííûõ ïîïóëÿ- öèé â) ðàñïðîñòðàíåíèå çíàíèé î êðóïíûõ òðàâîÿäíûõ ñ öåëüþ óñèëåíèÿ áëàãîïðèÿòíîãî îòíîøå- íèÿ ê íèì ñî ñòîðîíû íàñåëåíèÿ. Íàìå÷åíû òåððèòîðèè ïîòåíöèàëüíî ïðèãîäíûå äëÿ èíòðîäóê- öèè ýòîãî âèäà. The large part of Eurasia is undergoing now considerable economic and land use changes, which brings a threat to some endangered populations or even species, but on the other hand creates new opportunities for ecological restoration of former wilderness areas. Large herbivores are key species for numerous ecosystems being the link between producers (vegetation), and secondary consumers (predators), including people. -

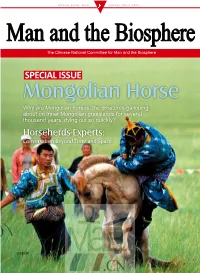

Mongolian Horse Why Are Mongolian Horses, the Creatures Galloping About on Inner Mongolian Grasslands for Several Thousand Years, Dying out So Quickly?

SPECIAL ISSUE 2010 SPECIAL ISSUE 2010 Man and the Biosphere Man and the Biosphere The Chinese National Committee for Man and the Biosphere SPECIAL ISSUE Mongolian Horse Why are Mongolian horses, the creatures galloping about on Inner Mongolian grasslands for several thousand years, dying out so quickly? Horseherds-Experts: Conversation Beyond Time and Space A home on the grassland. Photo: Ayin SPECIAL SPECIAL ISSUE 2010 Postal Distribution Code:82-253 Issue No.:ISSN 1009-1661 CN11-4408/Q US$5.00 The Silingol Grassland. Photo: He Ping Photo: The Silingol Grassland. This oil painting dates from 1986. The boy is called Chog and he is about 14 or 15 years old. This is about the time when livestock were starting to be distributed among individual households, just before the privatization of pasturelands. Now, 20 years later, the situation on the grasslands is very worrying. Desertification is largely caused by over-development and over-grazing. In the old days, the traditional nomadic way of life did no harm to the grasslands, now it has been replaced with privatized farms, the grassland is degenerating. Text and photo: Chen Jiqun (an artist specializing in oil painting and depicting grassland scenes. He lived in Juun Ujumucin, Silin ghol aimag (league), for 13 years from 1967) The Mongolian Horse – Taking us on a Long Journey Our editing team There are, perhaps, only a few animals in the world that are as deeply embedded into a culture as is the Mongolian Horse. This is an animal whose fate is so closely tied to a people that its situation is an indicator of both the health of the external environment and the culture upon which it relies. -

Montana 4-H / Open Ranch Horse RULES for Competitions 1

Montana 4-H / Open Ranch Horse RULES for Competitions 1. Project Overview The Montana 4-H Working Ranch Horse Project is a heritage based, activity rich program designed to pass on to today’s youth traditional practices of safe livestock handling from horseback. This is not a rodeo project, but instead a practical and exciting opportunity for youth to use horses for handling, sorting and moving cattle. This project also teaches mounted roping skills as a humane and useful livestock handling tool as well as branding techniques, housing and care of cattle and horses. Like all 4-H projects, Working Ranch Horse members will develop the qualities of leadership and responsibility that come with being engaged in 4-H. In today’s world, managing cattle from horseback is a disappearing tradition. Ranches are increasingly automated, using four-wheelers and other machines instead of horses. Many of the skills once learned for necessity are being lost. The 4-H Working Ranch Horse Program is designed to teach and preserve the age-old skills and traditions. 2. General Event Rules a. The intent of the competitions is to display your ability to perform ranch work type tasks while working horseback and showing CONTROL and SAFETY at all times. For example: Control is shown in horsemanship through responsiveness to rider cues. In cow work the intent is to work the cow in a calm manner as you would on a ranch (only as much pressure as needed to gain control of the cow). A trail class is an opportunity to display the ability for a person to work safely around and on-top a horse. -

The Caspian Horse of Iran

THE CASPIAN HORSE OF IRAN by Louise Firouz PREFACE Several years ago word spread that a new breed of horse, like a miniature Arabian. had been found on the shores of the Caspian in Iran. In 1965 five Caspian ponies were brought to Louise Firouz in Tehran for riding by her children. Louise Firouz was born in Washington, graduated at Cornell where she studied animal husbandry. classics, and English. In ) '157 she married Narcy Firouz and moved to Tehran where she is occupied in farming and raising horses. Following the arrival of the five Caspians, a three-year survey was begun to search for more of these horses. She covered part of an area from Astara to Pahlevi-Dej located east of the Caspian. About :0 ponies are estimated to live between Babol and Amol (Map 1). Six mares and five stallions were brought to the breeding farm at Norouzabad near Tehran. In 1966 a stud book was established to encourage purity 'Of the strain. Dr. Hosseinion, Tehran Veterinary College, regularly inspects foals and adults. The similarity between the Caspian and the horses pulling the chariot of Darius and the ponies on a bas-relief at Persepolis is significant. The above has been summarized from the illustrated article by Louise Firouz in Animals, June, 1970 (see Bibliography). My interest in horses ancient and modem stems from the Equidtze excavated at Kish, eight miles east of Babylon, by the Field Museum-Oxford University Joint Expedition to Iraq, 1923-34. In 1928 I was one of the Staff members of this Expedition under Field Director Louis Charles Watelin. -

The Stallion's Mane the Next Generation of Horses in Mongolia

The Stallion's Mane The Next Generation of Horses in Mongolia Amanda Hund World Learning- S.I.T. SA – Mongolia Fall Semester 2008 S. Ulziijargal Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the help and enthusiasm of many people, a few of which I would like to thank personally here: I would like to acknowledge Ulziijargal, Ganbagana and Ariunzaya for all their patience, help, and advice, Ulziihishig for his excellent logistical work and well placed connections and Munkhzaya for being a wonderful translator and travel partner and for never getting sick of talking about horses. I would also like to thank the families of Naraa, Sumyabaatar, and Bar, who opened their homes to me and helped me in so many ways, Tungalag for being a helpful advisor, my parents for giving me the background knowledge I needed and for their endless support, as well as all those herders, veterinarians, and horse trainers who were willing to teach me what they know. This research would not have been possible without the open generosity and hospitality of the Mongolian people. 2 Table of Contents Abstract...................................4 Introduction.............................5 Methods...................................8 The Mongolian Horse.............11 Ancestors................................14 Genetic Purity........................15 Mares.....................................16 Reproduction..........................17 Stallions..................................22 Bloodlines...............................25 Passion on the Tradition.........27 -

And Asiatic Wild Asses (Equus Hemionus) Using a Species-Specifi C Restriction Site in the Mitochondrial Cytochrome B Region

Mongolian Journal of Biological Sciences 2006 Vol. 4(2): 57-62 Differentiation of Meat Samples from Domestic Horses (Equus caballus) and Asiatic Wild Asses (Equus hemionus) Using a Species-Specifi c Restriction Site in the Mitochondrial Cytochrome b Region Ralph Kuehn1, Petra Kaczensky2, Davaa Lkhagvasuren3, Stephanie Pietsch1 and Chris Walzer2 1Molecular Zoology, Chair of Zoology, Technische Universität München, Am Hochanger 13, D-85354 Freising, Germany, E-mail: [email protected] 2Research Institute of Wildlife Ecology, University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna Savoyenstrasse 1, A- 1160 Vienna, Austria, E-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] 3Department of Zoology, Faculty of Biology, National University of Mongolia, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Recent studies suggest that Asiatic wild asses (Equus hemionus) are being increasingly poached in a commercial fashion. Part of the meat is believed to reach the meat markets in the capital Ulaanbaatar. To test this hypothesis, we collected 500 meat samples between February and May 2006. To differentiate between domestic horse (Equus caballus) and wild ass meat, we developed a restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assay based on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). We amplifi ed and sequenced a cytochrome b fragment (335 bp) and carried out a multialignment of the generated sequences for the domestic horse, the Asiatic wild ass, the domestic donkey (Equus asinus) and the Przewalski’s horse (Equus ferus przewalskii). We detected a species-specifi c restriction site (AatII) for the Asiatic wild ass, resulting in a specifi c restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) band pattern. This RFLP assay represents a rapid and cost-effective method to detect wild ass meat. -

Recreational Riding COURTESY TIMOTHY BRATTEN COURTESY Contents

American Paint Horse Association’s Guide to Recreational Riding COURTESY TIMOTHY BRATTEN COURTESY Contents Introducton .............................................................. 1 What do I need to know to get started? .....................2 Scenarios you may encounter on the trail ................. 3 What type of tack and gear do I need? ...................... 4 Is special attire required? .......................................... 4 Recreational riding safety and etiquette .................... 5 How do I organize a successful trail ride? ................. 6 Rules for your ride .................................................... 8 Guidelines for APHA club-sponsored rides ............... 9 APHA trail rides and Ride America® ......................... 9 Planning and organization aids for recreational riding .................................................. 10 Recreational riding checklists ................................. 10 Trail Ride Rules ...................................................... 11 Trail Ride Registration Form ................................... 11 Trail Ride Assumption of Risk and Release.............. 12 Trail Ride Participant Health Form ......................... 13 For more information on the American Paint Horse Association and what it can offer you, call (817) 834-2742. Visit APHA’s official Web site atapha.com he sun shines warmly on your back. Only a few feathery clouds drift across the sky. TA cool breeze blows lightly, rumpling your horse’s mane as you amble along the trail. Right now, the troubles of the world seem far behind you. On this perfect day, it’s just you, your Paint Horse and the great outdoors. Recreational riding is one of the most popular activities Recreational riding provides time to reflect on the day’s enjoyed by horse owners around the world. Whether you’re activities and plan for tomorrow. It allows you to relax your breaking ground over an unbeaten path, trekking across an mind and body and escape from the hassles of day-to-day life. -

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state.