How Age Friendly Is Bristol? Draft Baseline Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land at Cribbs Causeway

1. Welcome January 2014 Today’s Exhibition The Joint Venture This exhibition displays the latest proposals for a mixed-use Land at Cribbs Causeway is a joint venture development on Land at Cribbs Causeway which will be between Skanska & Deeley Freed set up in About Skanska submitted as an outline planning application in February. The 2010. The partnership utilises the strong Skanska is one of the world’s leading proposed development, which forms part of the wider Cribbs / local knowledge and relationships of both construction groups. We carry out all Patchway New Neighbourhood, will include a range of organisations as well as drawing upon the aspects of the construction, development housing, a new primary school, retail and community facilities, significant resources Skanska are investing into and infrastructure process - from financing new public open spaces and woodland planting. Bristol and the South West. projects, through design and construction right through to facilities management, operation Last November stakeholders, near neighbours and the The responsibility of the partnership is to and maintenance. We are currently delivering wider public gave feedback on the emerging proposals. The work with local communities, stakeholders schools and infrastructure projects in the South following boards show how feedback and results of further and partners to maximise the potential of the West, and have three offices in Bristol. site studies have informed the latest draft masterplan. Key site. This will include providing much needed issues raised included concerns around transport, traffic and housing, sporting facilities and recreational access especially in the context of the number of new homes areas, commercial opportunities and public being proposed on this site and coming forward within the infrastructure such as schools and community wider area. -

Urban Issues and Challenges

PAPER 2: HUMAN GEOGRAPHY Section A: Urban Issues and Challenges (Parts 1-5) Case study of a major city in a LIC or NEE: Rio de Janeiro An example of how urban planning improves the quality of life for the urban poor: Favela Bairro Project Case study of a major city in the UK: Bristol An example of an urban regeneration project: Temple Quarter Section B: The Changing Economic World (Parts 1-6) An example of how tourism can reduce the development gap: Jamaica A case study of an LIC or NEE: Nigeria A case study of an HIC: the UK An example of how modern industries can be environmentally sustainable: Torr Quarry Section C: The Challenge of Resource Management (27-29) Example of a large scale water management scheme: Lesotho Example of a local scheme in an LIC to increase water sustainability: The Wakel river basin project Section A: Urban Issues and Challenges (Parts 1-5) Case study of a major city in a LIC or NEE: Rio de Janeiro An example of how urban planning improves the quality of life for the urban poor: Favela Bairro Project Case study of a major city in the UK: Bristol An example of an urban regeneration project: Temple Quarter 2 Y10 – The Geography Knowledge – URBAN ISSUES AND CHALLENGES (part 1) 17 Urbanisation is….. The increase in people living in towns and cities More specifically….. In 1950 33% of the world’s population lived in urban areas, whereas in 2015 55% of the world’s population lived in urban areas. By 2050…. -

Bristol Arena Island Proposals, Temple Quarter, Bristol

TRANSPORT ASSESSMENT Bristol Arena Island Proposals, Temple Quarter, Bristol Prepared for Bristol City Council November 2015 1, The Square Temple Quay Bristol BS1 6DG Contents Section Page Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................................ vii Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Report Purpose ........................................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 BCC Scoping Discussions .............................................................................................. 1-1 1.4 Arena Operator Discussions ......................................................................................... 1-2 1.5 Report Structure.......................................................................................................... 1-2 Transport Policy Review...................................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 2-1 2.2 Local Policy .................................................................................................................. 2-1 2.2.1 The Development -

Bristol City Centre Retail Study: Stages 1 & 2

www.dtz.com Bristol City Centre Retail Study: Stages 1 & 2 Bristol City Council June 2013 DTZ, a UGL company One Curzon Street London W1J 5HD Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Contextual Review ......................................................................................................................... 5 3 Retail and Leisure Functions of Bristol City Centre’s 7 Retail Areas ............................................ 14 4 Basis of the Retail Capacity Forecasts .......................................................................................... 31 5 Quantitative Capacity for New Retail Development ................................................................... 43 6 Qualitative Retail Needs Assessment .......................................................................................... 50 7 Retailer Demand Assessment ...................................................................................................... 74 8 Commercial Leisure Needs Assessment ...................................................................................... 78 9 Review of Potential Development Opportunities ........................................................................ 87 10 Review of Retail Area and Frontage Designations .................................................................... 104 11 Conclusions and Implications for Strategy .............................................................................. -

Agenda Item 11 Bristol City

AGENDA ITEM 11 BRISTOL CITY COUNCIL CABINET 4 October 2012 REPORT TITLE: Governance Options Appraisal, Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives Ward(s) affected by this report: Citywide Strategic Director: Graham Sims, Interim Chief Executive Rick Palmer, Interim Strategic Director Neighbourhoods and City Development Report author: Julie Finch, Head of Museums, Galleries & Archives Contact telephone no. 0117 9224804 & e-mail address: [email protected] Report signed off by Simon Cook executive member: Leader Purpose of the report: This report outlines the governance option proposed for the Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives Services (BMGA). This report is led by the recommendations of the Select Committee Report that gained all party support in November 2009. The report identifies the most suitable model of governance for BMGA to support an improvement strategy and optimise enterprise activity creating a more sustainable future for the service and meet demand. RECOMMENDATION for Cabinet approval: 1. To agree in principle to the transfer of the BMGA to an independent trust at the existing funding levels of £3.7m subject to an agreed business case. 2. To adopt the governance model that will be a single independent museums trust, closely bound into the BCC family through specified interfaces and trustee compositions. Staff would become employees of the new organisation. The major assets will remain the property of the Council. 3. To agree to the implementation of phased approach to a change in governance 1 whereby Bristol City Council (BCC) delivers BMGA activities through a company limited by guarantee with charitable status. 4. To develop the business plan that will frame the transfer and all associated interfaces, service level agreements and entrustment agreements. -

Culture Leisure and Tourism Topic Paper Final Version

North Somerset Council Local Development Framework Core Strategy Topic paper Culture, leisure and tourism September 2007 Culture, Leisure and Tourism and Topic Paper This is part of a series of topic papers summarising the evidence base for the North Somerset Core Strategy document. Other topic papers available in this series: � Demography, health, social inclusion and deprivation � Housing � Economy � Retail � Settlement function and hierarchy � Resources (including minerals, waste, recycling, energy consumption) � Natural environment (including climate change, biodiversity, green infrastructure, countryside, natural environment and flooding) � Transport and communications � Sustainable construction / design quality including heritage � Summing up / spatial portrait For further information on this topic paper please contact: Planning Policy Team Development and Environment North Somerset Council Somerset House Oxford Street WestonsuperMare BS23 1TG Tel: 01275 888545 Fax: 01275 888569 localplan@nsomerset.gov.uk 1. Introduction 1.1 The scope of this topic paper is wide ranging covering those aspects of society which enrich our lives. This is everything from the most fundamental of community services and facilities such as the provision of schools and health services to ways of spending our leisure time whether it be as residents of North Somerset or as tourists. With regards to tourism there are obvious overlaps between this and the economic topic paper and the work which is underway on the Area Action Plans for Westonsuper Mare Town Centre and the Regeneration Area. No attempt has been made to cover every aspect of Culture, Leisure and Tourism. The intention has been to highlight those areas which may have the clearest implications for spatial/land use planning and especially the Core Strategy. -

Youth Culture and Nightlife in Bristol

Youth culture and nightlife in Bristol A report by: Meg Aubrey Paul Chatterton Robert Hollands Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies and Department of Sociology and Social Policy University of Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, UK In 1982 there were pubs and a smattering of (God help us) cocktail bars. The middle-aged middle classes drank in wine bars. By 1992 there were theme pubs and theme bars, many of them dumping their old traditional names in favour of ‘humorous’ names like The Slug and Lettuce, The Spaceman and Chips or the Pestilence and Sausages (actually we’ve made the last two up). In 2001 we have a fair few pubs left, but the big news is bars, bright, shiny chic places which are designed to appeal to women rather more than blokes with swelling guts. In 1982 they shut in the afternoons and at 11pm weekdays and 10.30pm Sundays. In 2001 most drinking places open all day and many late into the night as well. In 1982 we had Whiteladies Road and in 2001 we have The Strip (Eugene Byrne, Venue Magazine July, 2001 p23). Bristol has suddenly become this cosmopolitan Paris of the South West. That is the aspiration of the council anyhow. For years it was a very boring provincial city to live in and that’s why the music that’s come out of it is so exciting. Cos it’s the product of people doing it for themselves. That’s a real punk-rock ethic. (Ian, music goer, Bristol). Contents Contents 2 List of Tables 5 Introduction 6 Chapter 1. -

Century Park

Century Park One, two, three and four bedroom homes Lawrence Weston, Bristol Whether you’re looking for your first home, next home or forever Homes home, Curo can help. for Good We build quality, attractive homes designed for modern living, giving you confidence that you’re making a great investment in your family’s future. We believe a home is more than bricks and mortar; we create thoughtfully designed developments with connections, community and our customers at their heart. We’re proud to be a business with social objectives. That’s why, instead of having shareholders, we re-invest all our profits to achieve our purpose – to create Homes for Good. Century Park is a development of one, two, three and four bedroom homes. Situated on the North West edge of Bristol in Lawrence Weston, it offers the ideal location for both first time buyers and young families alike. Located within easy access of Bristol city centre, The Mall Cribbs Causeway, the M5 and beyond, and close to numerous parks and grassland areas, including the beautiful 650 acre Blaise Castle Estate. This image is from an imaginary viewpoint within an open space area. The purpose is to give a feel for the development and not an accurate description of each property. External materials, finishes and landscaping and the positions of garages may vary throughout the development. A selection of 128 new homes all finished to a high specification, surrounded by open green space and enhanced pedestrian and cycle routes. Contemporary design The properties at Century Park are built to the highest standards, benefiting from private gardens and off-street parking. -

Final Copy 2019 01 31 Charl

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Charles, Christopher Title: Psyculture in Bristol Careers, Projects and Strategies in Digital Music-Making General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Psyculture in Bristol: Careers, Projects, and Strategies in Digital Music-Making Christopher Charles A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of Ph. D. -

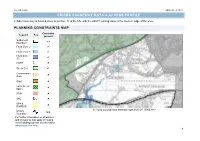

Cribbs Causeway Data & Access Profile

November 2020 Urban Place Profiles CRIBBS CAUSEWAY DATA & ACCESS PROFILE Cribbs Causeway is located close to junction 17 of the M5, with the A4018 running close to the western edge of the area. PLANNING CONSTRAINTS MAP Constraint Legend Key present Settlement N/A Boundary Flood Zone 2 Flood Zone 3 Flood Zone 3B AONB Green Belt Conservation Area SAM Local Green Space SSSI SAC SPA & RAMSAR Unitary © Crown copyright and database right 2020 OS 100023410 N/A Boundary For further information on all policies and constraints that apply (including listed buildings) please see the online adopted policies map. 1 November 2020 Urban Place Profiles KEY DEMOGRAPHIC STATISTICS POPULATION & HOUSEHOLD Population Additional Households dwellings Total 0-4 5-15 16-64 65+ 2011 completed 2011 Census since 590 48 64 398 80 Census 2011* 2018 MYE 838 67 126 555 89 243 148 % change 42% 40% 96% 40% 11% 2011 to 2018 *Based on residential land survey data 2011 CENSUS ECONOMIC ACTIVITY Economically No. Unemployed % Unemployed Active Cribbs Causeway 350 22 6.3% South Gloucestershire 143,198 5,354 3.7% Total 2011 CENSUS COMMUTER FLOWS The following section presents a summary of the commuter flows data for each area. The number of ‘resident workers’ and ‘workplace jobs’ are identified and shown below. Key flows between areas are also identified ‐ generally where flows are in excess of 5% Jobs Workers Job/Worker Ratio 6,477 324 20.0 According to 2011 Census travel to work data there were around 300 ‘working residents’ living in the area. Of these: 29% work within Bristol 10% work within the area with a further 19% working from home or with no fixed workplace (i.e. -

Rail Network Plan Options in the Cribbs Causeway Area

Welcome to your guide to transport X25 Cribbs Causeway- 75 Cribbs Causeway- 614 Thornbury- Rail Network Plan options in the Cribbs Causeway area. Getting around Portishead Hengrove Severn Beach to Worcester, Birmingham and the North This guide provides an overview of all transport options Cribbs Causeway and Cribbs Causeway Cribbs Causeway Thornbury in Cribbs Causeway and the surrounding areas. The Bus freqencies in Bus freqencies in Bus freqencies in Health Centre map overleaf shows all bus services, the train stations minutes minutes minutes surrounding areas Patchway, Gloucester and cycle paths. The bus services are colour coded to The Parade Daytime Evenings Daytime Evenings Daytime Evenings Thornbury to Cardiff and West Wales help you. Mon-Fri 60 2 jnys Mon-Fr 10 30 Filton, Royal Mail Mon-Fr 1 jny* - Rock Street In addition to public transport, the A summary of services is shown in the Bus Frequency Saturday 60 2 jnys Heron Gardens Saturday 10 30 Saturday - - to Stonehouse and Stroud following options are available: Guide below which includes approximate daytime and Filton Church Thornbury, Tesco, Severn Beach Sunday - - Sunday 30 30 Sunday - - Pilning Cam & Dursley evening frequencies for all days of the week. Daytime to Stroud Operated by First City Centre Bristol Four Towns and Vale Link Community Transport means up to 6pm and Evenings from 6pm. Operated by First Operated by Severnside Alveston Down Yate St Andrews Road Patchway Parkway to Didcot, Transport Thornbury and communities to the west of the M5 The numbers shown indicate how often the buses run. Bedminster Clifton Parkway, Passengers wishing to travel Portishead Tockington Shirehampton Down Montpelier Reading and are mainly served by Four Towns and Vale link For example the number 30 would show that a bus runs on this service must telephone Swindon Example Fare: Bishopsworth Filton Abbey Wood London community transport. -

Who Feeds Bristol' Report

Who feeds Bristol? Towards a resilient food plan Production • Processing • Distribution • Communities • Retail • Catering • Waste Research report written by Joy Carey A baseline study of the food system that serves Bristol and the Bristol city region March 2011 Foreword For over a thousand years, the supply and trade of food has been integral to the economic, social and cultural life of Bristol. During my career in public health I have always been aware not just of the paramount importance of food, but also of the contrasts and paradoxes it brings; from desperate shortage in refugee camps and conflict zones, to the plenty and variety in wealthy capital cities, the intense visibility of food in parts of the world like Africa and India, and of course its curious invisibility in the UK now that highly mechanised production, distribution, processing and retail operate beyond our everyday view. Bristol is regaining its awareness of food – for the health of our local economy, for the health of our people, and for the health of the ecosystems upon which our future food production will depend. We read dire predictions of potential global food shortages, and conflicting reports as to whether these problems are real or imagined, and whether the solution lies with more biotechnology or with less. Yet we cannot begin to assess whether our own food system is healthy and robust unless we know more about it. The task of tracking down and making sense of what information is available has not been easy. We are indebted to Joy Carey, who in a short time and with a very modest amount of funding, has pulled together information from numerous sources and pieced it all together into this important research report.