Antipsychotics and Seizures: What Are the Risks?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WELLBUTRIN SR Safely and Effectively

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION psychosis, hallucinations, paranoia, delusions, homicidal ideation, These highlights do not include all the information needed to use aggression, hostility, agitation, anxiety, and panic, as well as suicidal WELLBUTRIN SR safely and effectively. See full prescribing ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide. Observe patients information for WELLBUTRIN SR. attempting to quit smoking with bupropion for the occurrence of such symptoms and instruct them to discontinue bupropion and contact a WELLBUTRIN SR (bupropion hydrochloride) sustained-release tablets, healthcare provider if they experience such adverse events. (5.2) for oral use • Initial U.S. Approval: 1985 Seizure risk: The risk is dose-related. Can minimize risk by gradually increasing the dose and limiting daily dose to 400 mg. Discontinue if WARNING: SUICIDAL THOUGHTS AND BEHAVIORS seizure occurs. (4, 5.3, 7.3) See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. • Hypertension: WELLBUTRIN SR can increase blood pressure. Monitor blood pressure before initiating treatment and periodically during • Increased risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in children, treatment. (5.4) adolescents and young adults taking antidepressants. (5.1) • Activation of mania/hypomania: Screen patients for bipolar disorder and • Monitor for worsening and emergence of suicidal thoughts and monitor for these symptoms. (5.5) behaviors. (5.1) • Psychosis and other neuropsychiatric reactions: Instruct patients to contact a healthcare professional if such reactions occur. (5.6) --------------------------- INDICATIONS AND USAGE ---------------------------- • Angle-closure glaucoma: Angle-closure glaucoma has occurred in WELLBUTRIN SR is an aminoketone antidepressant, indicated for the patients with untreated anatomically narrow angles treated with treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). (1) antidepressants. -

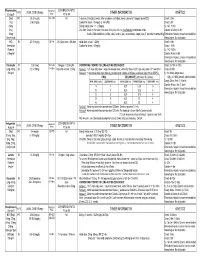

Medication Conversion Chart

Fluphenazine FREQUENCY CONVERSION RATIO ROUTE USUAL DOSE (Range) (Range) OTHER INFORMATION KINETICS Prolixin® PO to IM Oral PO 2.5-20 mg/dy QD - QID NA ↑ dose by 2.5mg/dy Q week. After symptoms controlled, slowly ↓ dose to 1-5mg/dy (dosed QD) Onset: ≤ 1hr 1mg (2-60 mg/dy) Caution for doses > 20mg/dy (↑ risk EPS) Cmax: 0.5hr 2.5mg Elderly: Initial dose = 1 - 2.5mg/dy t½: 14.7-15.3hr 5mg Oral Soln: Dilute in 2oz water, tomato or fruit juice, milk, or uncaffeinated carbonated drinks Duration of Action: 6-8hr 10mg Avoid caffeinated drinks (coffee, cola), tannics (tea), or pectinates (apple juice) 2° possible incompatibilityElimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 5mg/ml soln Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable HCl IM 2.5-10 mg/dy Q6-8 hr 1/3-1/2 po dose = IM dose Initial dose (usual): 1.25mg Onset: ≤ 1hr Immediate Caution for doses > 10mg/dy Cmax: 1.5-2hr Release t½: 14.7-15.3hr 2.5mg/ml Duration Action: 6-8hr Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable Decanoate IM 12.5-50mg Q2-3 wks 10mg po = 12.5mg IM CONVERTING FROM PO TO LONG-ACTING DECANOATE: Onset: 24-72hr (4-72hr) Long-Acting SC (12.5-100mg) (1-4 wks) Round to nearest 12.5mg Method 1: 1.25 X po daily dose = equiv decanoate dose; admin Q2-3wks. Cont ½ po daily dose X 1st few mths Cmax: 48-96hr 25mg/ml Method 2: ↑ decanoate dose over 4wks & ↓ po dose over 4-8wks as follows (accelerate taper for sx of EPS): t½: 6.8-9.6dy (single dose) ORAL DECANOATE (Administer Q 2 weeks) 15dy (14-100dy chronic administration) ORAL DOSE (mg/dy) ↓ DOSE OVER (wks) INITIAL DOSE (mg) TARGET DOSE (mg) DOSE OVER (wks) Steady State: 2mth (1.5-3mth) 5 4 6.25 6.25 0 Duration Action: 2wk (1-6wk) Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 10 4 6.25 12.5 4 Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable 20 8 6.25 12.5 4 30 8 6.25 25 4 40 8 6.25 25 4 Method 3: Admin equivalent decanoate dose Q2-3wks. -

Adjunctive Risperidone Treatment for Antidepressant-Resistant

Supplementary Online Content Krystal JH, Rosenheck RA, Cramer JA, et al. Adjunctive risperidone treatment for antidepressant- resistant symptoms of chronic military service–related PTSD. JAMA. 2011;306(5):493-502. eTable 1. Follow-up Drugs Started After Randomization eTable 2. Baseline Medications eTable 3. Number of Different Drugs From Each Major Class Each Patient Is Taking at Baseline eTable 4. Baseline Medication Combinations eTable 5. Adverse Events eFigure 1. Product-Limit Survival Estimates With Number of Subjects at Risk eFigure 2. Percentage of Veterans at Each CAPS Severity Level at 24 Weeks, by Treatment This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/23/2021 eTable 1. Follow-up Drugs Started After Randomization Placebo Risperidone N= 134 N= 133 Total Patients % Patients % Patients % p-value Drugs started after randomization 46 34.3 59 44.4 105 39.3 0.10 Adrenergic Drugs 4 3.0 5 3.8 9 3.4 0.75 Atenolol 0 0.0 2 1.5 2 0.7 Metoprolol 3 2.2 2 1.5 5 1.9 Propranolol 1 0.7 1 0.8 2 0.7 Opiates 22 16.4 19 14.3 41 15.4 0.73 Codeine 1 0.7 1 0.8 2 0.7 Fentanyl 3 2.2 0 0.0 3 1.1 Hydrocodone (With Or Without 13 9.7 10 7.5 23 8.6 Acetaminophen) Methadone 1 0.7 0 0.0 1 0.4 Morphine 3 2.2 2 1.5 5 1.9 Oxycodone (With Or Without 4 3.0 7 5.3 11 4.1 Acetaminophen) Tramadol 3 2.2 2 1.5 5 1.9 Psycho-Stimulants 0 0.0 2 1.5 2 0.7 0.25 Methylphenidate 0 0.0 2 1.5 2 0.7 Muscle -

Paliperidone Long Acting Injection Patient Information

Paliperidone (pala-pera-done) long acting injection Patient Information - Hillmorton Hospital Pharmacy www.healthinfo.org.nz Why have I been prescribed paliperidone? Paliperidone is used to treat schizophrenia, psychosis and similar conditions. It can also be used to treat mania. A person diagnosed with schizophrenia may hear voices talking to them or about them. They may also become suspicious or paranoid. Some people also have problems with their thinking and feel that other people can read their thoughts. These are called “positive Paliperidone Injection Long Acting symptoms”. Paliperidone can help to relieve these symptoms. Many people with schizophrenia also experience “negative symptoms”. They feel tired and lacking in energy and may become quite inactive and withdrawn. Paliperidone may help relieve these symptoms as well. Paliperidone may also be prescribed for people who have had side effects such as strange movements and shaking, with older types of antipsychotics. Paliperidone is a close relative of the antipsychotic risperidone. It’s side effect profile is similar but has the advantage of being able to be given as a once a month injection. What exactly is paliperidone? Is paliperidone safe for me? It is usually safe to take paliperidone Paliperidone is one of a group of regularly as prescribed by your doctor, but medicines used to treat schizophrenia it doesn’t suit everyone. Let your doctor and similar disorders. These illnesses are know if any of the following apply to you, sometimes referred to as psychoses, as extra care may be needed: hence the name given to this group of medicines, which is the “antipsychotics”. -

Phencyclidine: an Update

Phencyclidine: An Update U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES • Public Health Service • Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration Phencyclidine: An Update Editor: Doris H. Clouet, Ph.D. Division of Preclinical Research National Institute on Drug Abuse and New York State Division of Substance Abuse Services NIDA Research Monograph 64 1986 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administratlon National Institute on Drug Abuse 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, Maryland 20657 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, DC 20402 NIDA Research Monographs are prepared by the research divisions of the National lnstitute on Drug Abuse and published by its Office of Science The primary objective of the series is to provide critical reviews of research problem areas and techniques, the content of state-of-the-art conferences, and integrative research reviews. its dual publication emphasis is rapid and targeted dissemination to the scientific and professional community. Editorial Advisors MARTIN W. ADLER, Ph.D. SIDNEY COHEN, M.D. Temple University School of Medicine Los Angeles, California Philadelphia, Pennsylvania SYDNEY ARCHER, Ph.D. MARY L. JACOBSON Rensselaer Polytechnic lnstitute National Federation of Parents for Troy, New York Drug Free Youth RICHARD E. BELLEVILLE, Ph.D. Omaha, Nebraska NB Associates, Health Sciences Rockville, Maryland REESE T. JONES, M.D. KARST J. BESTEMAN Langley Porter Neuropsychiatric lnstitute Alcohol and Drug Problems Association San Francisco, California of North America Washington, D.C. DENISE KANDEL, Ph.D GILBERT J. BOTV N, Ph.D. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Cornell University Medical College Columbia University New York, New York New York, New York JOSEPH V. -

Alcohol Withdrawal

Alcohol withdrawal TERMINOLOGY CLINICAL CLARIFICATION • Alcohol withdrawal may occur after cessation or reduction of heavy and prolonged alcohol use; manifestations are characterized by autonomic hyperactivity and central nervous system excitation 1, 2 • Severe symptom manifestations (eg, seizures, delirium tremens) may develop in up to 5% of patients 3 CLASSIFICATION • Based on severity ○ Minor alcohol withdrawal syndrome 4, 5 – Manifestations occur early, within the first 48 hours after last drink or decrease in consumption 6 □ Manifestations develop about 6 hours after last drink or decrease in consumption and usually peak about 24 to 36 hours; resolution occurs in 2 to 7 days 7 if withdrawal does not progress to major alcohol withdrawal syndrome 4 – Characterized by mild autonomic hyperactivity (eg, tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, hyperreflexia), mild tremor, anxiety, irritability, sleep disturbances (eg, insomnia, vivid dreams), gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, anorexia, nausea, vomiting), headache, and craving alcohol 4 ○ Major alcohol withdrawal syndrome 5, 4 – Progression and worsening of withdrawal manifestations, usually after about 24 hours from the onset of initial manifestations 4 □ Manifestations often peak around 50 hours before gradual resolution or may continue to progress to severe (complicated) withdrawal, particularly without treatment 4 – Characterized by moderate to severe autonomic hyperactivity (eg, tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, hyperreflexia, fever); marked tremor; pronounced anxiety, insomnia, -

Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss

Supplemental Material can be found at: /content/suppl/2020/12/18/73.1.202.DC1.html 1521-0081/73/1/202–277$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/pharmrev.120.000056 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 73:202–277, January 2021 Copyright © 2020 by The Author(s) This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC Attribution 4.0 International license. ASSOCIATE EDITOR: MICHAEL NADER Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss Antonio Inserra, Danilo De Gregorio, and Gabriella Gobbi Neurobiological Psychiatry Unit, Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Abstract ...................................................................................205 Significance Statement. ..................................................................205 I. Introduction . ..............................................................................205 A. Review Outline ........................................................................205 B. Psychiatric Disorders and the Need for Novel Pharmacotherapies .......................206 C. Psychedelic Compounds as Novel Therapeutics in Psychiatry: Overview and Comparison with Current Available Treatments . .....................................206 D. Classical or Serotonergic Psychedelics versus Nonclassical Psychedelics: Definition ......208 Downloaded from E. Dissociative Anesthetics................................................................209 F. Empathogens-Entactogens . ............................................................209 -

Second-Generation Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics: a PRACTICAL GUIDE Understanding Each of These Medications’ Unique Properties Can Optimize Patient Care

Second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics: A PRACTICAL GUIDE Understanding each of these medications’ unique properties can optimize patient care Brittany L. Parmentier, PharmD, MPH, here are currently 7 FDA-approved second-generation long-acting BCPS, BCPP 1-7 Clinical Assistant Professor injectable antipsychotics (LAIAs). These LAIAs provide a Department of Pharmacy Practice Tunique dosage form that allows patients to receive an antipsy- The University of Texas at Tyler Fisch College of Pharmacy chotic without taking oral medications every day, or multiple times per Tyler, Texas day. This may be an appealing option for patients and clinicians, but Disclosure The author reports no financial relationships with any because there are several types of LAIAs available, it may be difficult to companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with determine which LAIA characteristics are best for a given patient. manufacturers of competing products. Since the FDA approved the first second-generation LAIA, risperidone long-acting injectable (LAI),1 in 2003, 6 additional second-generation LAIAs have been approved: • aripiprazole LAI • aripiprazole lauroxil LAI • olanzapine pamoate LAI • paliperidone palmitate monthly injection • paliperidone palmitate 3-month LAI • risperidone LAI for subcutaneous (SQ) injection. When discussing medication options with patients, clinicians need to consider factors that are unique to each LAIA. In this article, I describe the similarities and differences among the second-generation LAIAs, and address common questions about these medications. A major potential benefit: Increased adherence One potential benefit of all LAIAs is increased medication adherence com- pared with oral antipsychotics. One meta-analysis of 21 randomized con- trolled trials (RCTs) that compared LAIAs with oral antipsychotics and Current Psychiatry GEORGE MATTEI/SCIENCE SOURCE GEORGE MATTEI/SCIENCE Vol. -

INVEGA SUSTENNA® (Paliperidone Palmitate)

INVEGA SUSTENNA® INVEGA SUSTENNA® (paliperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable suspension, for intramuscular use (paliperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable suspension, for intramuscular use --------------------------- DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS --------------------------- HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION Extended-release injectable suspension: 39 mg/0.25 mL, 78 mg/0.5 mL, 117 mg/0.75 mL, These highlights do not include all the information needed to use 156 mg/mL, or 234 mg/1.5 mL (3) INVEGA SUSTENNA® safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for INVEGA SUSTENNA®. ----------------------------------- CONTRAINDICATIONS ----------------------------------- INVEGA SUSTENNA® (paliperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable Known hypersensitivity to paliperidone, risperidone, or to any excipients in suspension, for intramuscular use INVEGA SUSTENNA®. (4) Initial U.S. Approval: 2006 -----------------------------WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ----------------------------- WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS • Cerebrovascular Adverse Reactions, Including Stroke, in Elderly Patients with WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS Dementia-Related Psychosis: Increased incidence of cerebrovascular adverse See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. reactions (e.g. stroke, transient ischemic attack). (5.2) • Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome: Manage with immediate discontinuation of Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drug and close monitoring. (5.3) drugs are -

Treatment of Adult Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Tool

Section: A B C D E F G Resources References Treatment of Adult Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Tool This tool is designed to support primary care providers in the treatment of adult patients (≥ 18 years) who have major depressive disorder (MDD). MDD is the most prevalent depressive disorder, and approximately 7% of Canadians meet the diagnostic criteria every year.1,2 The treatment of MDD involves psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy. Providers should work with patients to create a treatment plan together using providers’ clinical expertise and keeping in mind the patient’s preferences, as well as the practicality, feasibility, availability and affordability of treatment. TABLE OF CONTENTS pg. 1 Section A: Overview of MDD pathway pg. 6 Section E: Complementary and alternative medicine pg. 2 Section B: Assessing suicidality and managing pg. 7 Section F: Follow-up and monitoring suicide-related behaviour pg. 9 Section G: Special patient populations pg. 3 Section C: Psychotherapy options pg. 10 Resources pg.3 Section D: Pharmacotherapy management SECTION A: Overview of MDD pathway Patient has suspected depression Talking Points It is important to provide your patient with non-judgmental care (e.g. “Being Consider unexpected life events (e.g. death in the family, diagnosed with depression is nothing to be ashamed of, it is very common and change in family status, financial crisis). Consider special many adults are diagnosed with it every year”) patient populations. • Don’t use clinical/psychiatric language (e.g. “mental health,” “psychiatric,” and/or “maladaptive”) unless the patient uses these terms first • Use understandable language for cognitive distortions (e.g. -

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (Also Belong to Psychiatric Medication Category) • Codeine (In 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • codeine (in 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No. 1/2/3/4, Fiorinal® C, Benzodiazepines Codeine Contin, etc.) • heroin • alprazolam (Xanax®) • hydrocodone (Hycodan®, etc.) • chlordiazepoxide (Librium®) • hydromorphone (Dilaudid®) • clonazepam (Rivotril®) • methadone • diazepam (Valium®) • morphine (MS Contin®, M-Eslon®, Kadian®, Statex®, etc.) • flurazepam (Dalmane®) • oxycodone (in Oxycocet®, Percocet®, Percodan®, OxyContin®, etc.) • lorazepam (Ativan®) • pentazocine (Talwin®) • nitrazepam (Mogadon®) • oxazepam ( Serax®) Alcohol • temazepam (Restoril®) Inhalants Barbiturates • gases (e.g. nitrous oxide, “laughing gas”, chloroform, halothane, • butalbital (in Fiorinal®) ether) • secobarbital (Seconal®) • volatile solvents (benzene, toluene, xylene, acetone, naptha and hexane) Buspirone (Buspar®) • nitrites (amyl nitrite, butyl nitrite and cyclohexyl nitrite – also known as “poppers”) Non-Benzodiazepine Hypnotics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • chloral hydrate • zopiclone (Imovane®) Other • GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate) • Rohypnol (flunitrazepam) CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM STIMULANTS Amphetamines Caffeine • dextroamphetamine (Dexadrine®) Methelynedioxyamphetamine (MDA) • methamphetamine (“Crystal meth”) (also has hallucinogenic actions) • methylphenidate (Biphentin®, Concerta®, Ritalin®) • mixed amphetamine salts (Adderall XR®) 3,4-Methelynedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy) (also has hallucinogenic actions) Cocaine/Crack -

Review of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacogenetics in Atypical Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics

pharmaceutics Review Review of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacogenetics in Atypical Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics Francisco José Toja-Camba 1,2,† , Nerea Gesto-Antelo 3,†, Olalla Maroñas 3,†, Eduardo Echarri Arrieta 4, Irene Zarra-Ferro 2,4, Miguel González-Barcia 2,4 , Enrique Bandín-Vilar 2,4 , Victor Mangas Sanjuan 2,5,6 , Fernando Facal 7,8 , Manuel Arrojo Romero 7, Angel Carracedo 3,9,10,* , Cristina Mondelo-García 2,4,* and Anxo Fernández-Ferreiro 2,4,* 1 Pharmacy Department, University Clinical Hospital of Ourense (SERGAS), Ramón Puga 52, 32005 Ourense, Spain; [email protected] 2 Clinical Pharmacology Group, Institute of Health Research (IDIS), Travesía da Choupana s/n, 15706 Santiago de Compostela, Spain; [email protected] (I.Z.-F.); [email protected] (M.G.-B.); [email protected] (E.B.-V.); [email protected] (V.M.S.) 3 Genomic Medicine Group, CIMUS, University of Santiago de Compostela, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Spain; [email protected] (N.G.-A.); [email protected] (O.M.) 4 Pharmacy Department, University Clinical Hospital of Santiago de Compostela (SERGAS), Citation: Toja-Camba, F.J.; 15706 Santiago de Compostela, Spain; [email protected] Gesto-Antelo, N.; Maroñas, O.; 5 Department of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Technology and Parasitology, University of Valencia, Echarri Arrieta, E.; Zarra-Ferro, I.; 46100 Valencia, Spain González-Barcia, M.; Bandín-Vilar, E.; 6 Interuniversity Research Institute for Molecular Recognition and Technological Development,