Indians in Britain!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bristol: a City Divided? Ethnic Minority Disadvantage in Education and Employment

Intelligence for a multi-ethnic Britain January 2017 Bristol: a city divided? Ethnic Minority disadvantage in Education and Employment Summary This Briefing draws on data from the 2001 and 2011 Figure 1. Population 2001 and 2011. Censuses and workshop discussions of academic researchers, community representatives and service providers, to identify 2011 patterns and drivers of ethnic inequalities in Bristol, and potential solutions. The main findings are: 2001 • Ethnic minorities in Bristol experience greater disadvantage than in England and Wales as a whole in 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% education and employment and this is particularly so for White British Indian Black African Black African people. White Irish Pakistani Black Caribbean Gypsy or Irish Traveller Bangladeshi Other Black • There was a decrease in the proportion of young people White other Chinese Arab with no educational qualifications in Bristol, for all ethnic Mixed Other Asian Any other groups, between 2001 and 2011. • Black African young people are persistently disadvantaged Source: Census 2001 & 2011 in education compared to their White peers. • Addressing educational inequalities requires attention Ethnic minorities in Bristol experience greater disadvantage to: the unrepresentativeness of the curriculum, lack of than the national average in education and employment, diversity in teaching staff and school leadership and poor as shown in Tables 1 and 2. In Education, ethnic minorities engagement with parents. in England and Wales on average have higher proportions • Bristol was ranked 55th for employment inequality with qualifications than White British people but this is between White British and ethnic minorities. not the case in Bristol, and inequality for the Black African • People from Black African (19%), Other (15%) and Black Caribbean (12.7%) groups had persistently high levels of Measuring Local Ethnic Inequalities unemployment. -

New Forecasts for the Uk's Ethnic Groups

THE FUTURE IS DIVERSITY: NEW FORECASTS FOR THE UK’S ETHNIC GROUPS Philip Rees1, Pia Wohland2, Stephen Clark1, Nik Lomax1, and Paul Norman1 1School of Geography, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK 2 Hull York Medical School, University of Hull, Hull, HU6 7RX, UK Contact: [email protected] Paper for the European Population Conference, 31 August to 3 September, 2016, Mainz, Germany Abstract Developed countries with below replacement fertility face population ageing. This is slowed by a net inflow of international migrants. The influx leads to a population of increasing ethnic diversity. Most researchers focus on a historical understanding of the ethnic transition process. We use this understanding to forecast the population of the United Kingdom, projecting the ethnic transition forward for 50 years. This chapter describes the context, model, estimates and assumptions for projections of ethnic group populations in England at local authority scale, and in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Demographic component rates for ethnic populations are estimated using 2001 and 2011 Census data and vital statistics. A bi-regional cohort-component model is used with assumptions are aligned to recent official projections. We pay special attention to international migration assumptions because of the prospects of a new relationship between the UK and the rest of the European Union, consequent on UK electors voting in the referendum of 23 June 2016 to leave the European Union. Official assumptions and project assumptions about UK international migration are compared for their direct effect on the UK population between 2011 and 2061. There are also indirect effects through the higher natural increase for younger groups, which we illustrate for one set of assumptions. -

Who Identifies As Welsh? National

November 2014 DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Who identifies asWelsh? National identities and ethnicity in Wales Summary • In Wales, 1.8 million people identify only as Welsh (58% of • People born in Wales are more likely to report only a Welsh the population) and 218,000 identify as Welsh and British national identity (76%). People born in Oceania and North (7% of the population). America and the Caribbean are more likely to report only a Welsh national identity (14% and 10% respectively) than • Mixed ethnic groups are more likely to identify with only people born in England (8%). a Welsh national identity than all other ethnic minority groups, with the highest proportion being amongst the White and Black Caribbean (59%) group. Introduction Since devolution, the Welsh Government has sought to • Mixed groups are more likely to identify only as Welsh support a common Welsh national identity through the ‘One (47%) than mixed groups in England (46%) and Scotland Wales’ strategy. This has included, for example, strengthening (37%) identify as English or Scottish only. the place of ‘Wales in the World’ and continued support for 1 • The ethnic groups in Wales most likely to identify only as the Welsh language. The inclusion of a question on national British are Bangladeshi (64%), Pakistani (56%) and Black identity in the 2011 Census provides us with an opportunity Caribbean (41%). to examine how people living in Wales describe themselves. The Census shows that 58% of people living in Wales identify • Welsh only national identity is reported more for younger only as Welsh and a further 7% identify as Welsh and British.2 people aged 0 to 17 than those aged 18 or older. -

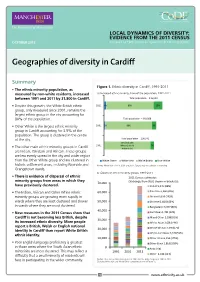

Geographies of Diversity in Cardiff

LOCAL DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS OCTOBER 2013 Prepared by ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Geographies of diversity in Cardiff Summary Figure 1. Ethnic diversity in Cardiff, 1991-2011 • The ethnic minority population, as measured by non-white residents, increased a) Increased ethnic minority share of the population, 1991-2011 between 1991 and 2011 by 31,800 in Cardiff. Total population – 346,090 • Despite this growth, the White British ethnic 2011 4% 80% 15% group, only measured since 2001, remains the largest ethnic group in the city accounting for 80% of the population. Total population – 310,088 • Other White is the largest ethnic minority 2001 2% 88% 9% group in Cardiff accounting for 3.5% of the population. The group is clustered in the centre of the city. Total population – 296,941 93% (includes 1991 White Other & 7% • The other main ethnic minority groups in Cardiff White Irish) are Indian, Pakistani and African. These groups are less evenly spread in the city and wider region than the Other White group and are clustered in White Other White Irish White British Non-White historic settlement areas, including Riverside and Notes: White Irish <1% in 2001 and 2011. Figures may not add due to rounding. Grangetown wards. b) Growth of ethnic minority groups, 1991-2011 • There is evidence of dispersal of ethnic 2011 Census estimates minority groups from areas in which they 70,000 (% change from 2001 shown in brackets): have previously clustered. Indian 9,435 (88%) • The Indian, African and Other White ethnic 60,000 Pakistani 6,960 (40%) minority groups are growing more rapidly in African 6,639 (162%) wards where they are least clustered and slower 50,000 Chinese 6,182 (105%) in wards where they are most clustered. -

Final Copy 2019 05 07 Awad

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Awad, Will Title: ‘I’m a professional businessman not a professional Pakistani’ Media Representation of South Asian Businessmen in Thatcherite Britain, 1979-1990. General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. ‘I’m a professional businessman not a professional Pakistani’: Media Representation of South Asian Businessmen in Thatcherite Britain, 1979-1990. William Alexander Awad A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts, December 2018. -

North West Leicestershire District Council

Coalville (Ward) Demographics – Population Age structure Ethnic group Marital status Country of birth Religion Housing – Average House Price Number of Houses Housing tenure Housing Type Council tax band Page 1 of 14 Crime – Burglary, Assault Criminal damage, Theft (vehicle) Fires attended Other – Occupation groups Economically active / inactive General Health Qualifications and students Indices of deprivation Sources - Page 2 of 14 Demographics – Population Total population (2001) North West Great Coalville Leicestershire Britain All People 4494 85503 57103923 Males 2182 42240 27758419 Females 2312 43263 29345504 % of District population 5.2% Coalville Ward makes up 5.2% of the population for North West Leicestershire. Age structure Coalville No of People People aged 0 - 4 284 People aged 5 - 7 171 People aged 8 - 9 118 People aged 10 - 14 291 People aged 15 57 People aged 16 - 17 109 People aged 18 - 19 103 People aged 20 - 24 242 People aged 25 - 29 349 People aged 30 - 44 1036 People aged 45 - 59 743 People aged 60 - 64 201 People aged 65 - 74 374 People aged 75 - 84 267 People aged 85 - 89 93 People aged 90 & over 58 The table above shows the break down of the population in Coalville by age groups. Page 3 of 14 Age structure – The graph below looks at the age structure as a % and compares Coalville with that of North West Leicestershire. 25 23.04 23.02 21.21 20 Coalville Nortn West Leicestershire 16.53 15 10 8.39 8.32 7.76 6.47 6.42 6.32 5.99 5.89 5.94 5.84 5.38 5.06 4.77 5 4.47 3.8 3.6 2.62 2.59 2.42 2.29 2.29 2.07 1.95 1.27 1.29 1.24 1.22 0.51 0 0 - 4 5 - 7 8 - 9 10 - 14 15 16 - 17 18 - 19 20 - 24 25 - 29 30 - 44 45 - 59 60 - 64 65 - 74 75 - 84 85 - 89 90 & over The graph shows which age groups are most predominant. -

White Flight: the Emerging Story

When connected to the BHPS, the survey is • information can be linked to ward-level one of the few in the western world making it census data possible to track both the demographic • unlike national surveys, this allows for the backgrounds and attitudes of large numbers of analysis of how attitudes change at local Contact with individuals over time. level, how moving is connected to attitudes, immigrants and and how the local affects the national. minorities is not Rich data on mixed marriages, mixed-race individuals, friendships and households will Policy implications – what White flight: as important enable researchers to explore whether these the research says as some believe factors are associated with less white British Contact with immigrants and minorities in changing people leaving an area, lower levels of anti- is not as important as some believe in the emerging story attitudes. immigration sentiment and right-wing voting. changing attitudes because diverse areas are Pioneering research – a case study Diverse areas also transient, and transience affects white Other features of Understanding Society that attitudes more than diversity. are transient make the research possible include: – this affects • the large sample size permits analysis of Greater opposition in local authority areas white attitudes people living in ethnically diverse wards compared with smaller wards can be more than (segregated or integrated) and relatively explained by the idea that people with few white wards adjoining diverse ones face-to-face contacts with immigrants and diversity. • Wave 1 of the survey captured information minorities can be threatened by an awareness from 200 BNP and 200 UKIP supporters, of ethnic change in their wider area, but this Institute for Social and Economic sufficient to test a range of interesting sense of threat is reduced by contact with Research (ISER) variables minorities and immigrants who live close by. -

Bristol Demographic Information Pack

Health and Social Care Bristol Demographic Information Pack V 1.0 June 2011 Contents Page Content Page Overview and Introduction 3 Community Engagement map 5 Population Profile 6 Equalities 6 Population by Gender 7 Population by Faith 7 Population by Ethnicity 7 Demographic Context 8 JSNA Key Findings 10 Key Health Indicators 12 Quality of Life Survey 12 Quality of Life for the Older Population of Bristol 17 Needs Groups 17 Dementia 17 Learning Disability 17 Adults with a Physical Disability 18 Sensory Impairment 18 Adults with Mental health problems 18 Carers 18 Falls in the over 65's 19 Health and Social Care provided Services 19 Residential and Nursing Care 19 Residential and Nursing Placements 20 Community Care Packages 21 Health and Social Care Budget 23 Page 2 of 24 HSC Community Engagement Information Pack Overview and Introduction Across the country, the provision of health and social care for adults (people aged 18 years and over) is going through major change. This is because of a number of pressures that affect us all in one way or another:- • there will be a rise in the number of older people and fewer younger people in the workforce to support the cost of public services • people expect more of modern social care services and rightly demand higher quality • the Government is demanding change and across the country, councils are working hard to provide good, high quality services within a reducing budget These things mean that the way we currently do things is neither sustainable nor desirable for the future. Like other councils, Bristol is looking at the way social care support is provided for adults who need it. -

Service User Data Report: Ethnicity and Sexual Orientation (Sept 2014)

Service User Data report: Ethnicity and Sexual Orientation (Sept 2014) 1.0 Intoduction: The Equality Act (2010) imposes a duty on all public bodies carrying out public functions to promote equality and eliminate discrimination. There are nine protected characteristics covered by the duty: age, sex, race including nationality and ethnicity, gender reassignment, sexual orientation, religion or belief, disability, marriage and civil partnership and pregnancy and maternity. Specific duties that need to be undertaken: . Annually publish relevant, proportionate information demonstrating compliance with the equality duty. The information must be published by on 31 January each year and in an easily accessible format. Consideration needs to be given to the following: • Eliminate unlawful discrimination, harassment and victimisation and other conduct prohibited by the Equality Act 2010 • Advance equality of opportunity between people from different groups; and • Foster good relations between people from different groups . A year on year snapshot comparison of trust service referral caseload by age, gender, ethnicity, religion, marital status, sexual orientation, pregnancy & maternity, gender re-assignment and disability. 2.0 Methodology: As agreed with the Equality & Human Rights Steering Group, there will be quarterly reports which focus on 2-3 of the 9 characteristics at a time. This first report will focus on Ethnicity and Sexual Orientation and will be broken down by Directorate and Borough. • Data will be a snapshot of the Trust’s referral caseload as at 31st March each year. Wherever necessary low numbers have been replaced with the < value, for the purpose of preserving anonymity . Comparisons, where made, are against ONS (Office of National Statistics) census 2011 3.0 Ethinicity: We have used the short list for Ethnicity categories as used by ONS. -

The Ageing of the Ethnic Minority Populations of England and Wales: Findings from the 2011 Census

The ageing of the ethnic minority populations of England and Wales: findings from the 2011 census A briefing paper from the Centre for Policy on Ageing June 2013 The Centre for Policy on Ageing was set up by the Nuffield Foundation in 1947 and, in 2012, celebrated 65 years of policy analysis and information provision on older age issues during which it has produced over 150 reports and reviews. CPA is an independent charity promoting the interests of older people through research, policy analysis and the dissemination of information. The Centre aims to raise awareness of issues around ageing, influence the development of policies to enable older people to live their lives as they choose, and to support good practice. CPA’s overarching focus since its inception has been on empowering older people to shape their own lives and the services they receive. The fundamental touchstone of its approach is to discover and advocate what older people themselves want and need. CPA is currently working in partnership with the Joseph Rowntree Foundation to support their Ageing Society programme which aims to respond positively to the opportunities and challenges of an ageing society. The purpose of this briefing is to examine the ageing of the ethnic minority populations of England and Wales as revealed by the 2011 census. It complements the 2010 CPA/Runnymede report, The future ageing of the ethnic minority population of England and Wales which, using the 2001 census as a base, projected ethnic minority ageing for England and Wales to 2051. The ageing characteristics of individual ethnic groups are examined and compared through key statistics and the ‘population pyramids’ for each group. -

London's Changing Ethnic Landscape, 2001Œ2011

London’s Changing Ethnic Landscape, 2001–2011: A Cartographic Exploration Ron Johnston, Michael Poulsen, and James Forrest Abstract London’s population became increasing more diverse ethnically over the decade 2001–2011, a period when the White population declined, with many commentators suggesting that there has been ‘White flight’ from some districts in the face of ‘invasion’ by members of ethnic minority groups. To examine how extensively the city’s ethnic landscape changed during that period – and whether suggestions of the operation of ‘invasion and succession processes’ are valid – this article reports on statistical mapping of small area data for the two censuses. The results identify clearly-defined, substantial blocks of territory within the urban residential fabric where members of each of the main census respondent self-identified ethnic groups are concentrated. These have expanded outwards, into areas from which the White population has clearly withdrawn, though in most cases the rate of cluster areal expansion has been less than the groups’ numerical growth. Publication of the results of the 2011 Census of England and Wales in early 2013 stimulated considerable media debate regarding the country’s changing ethnic composition, with commentators focusing their attention on the substantial changes to London’s ethnic mix.1 Some emphasised the geography of those changes, in particular the expansion of parts of London – as well as other cities – where Whites were now in a minority. How extensive have the changes in London’s residential landscape been? We use a recently- developed method of identifying the areas where different ethnic groups are concentrated to portray the city’s changing ethnic geography. -

Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (Bame) Women, Mental

population. Men appear to be more susceptible to BLACK, ASIAN AND the virus than women. So, whether it is BAME MINORITY ETHNIC women themselves or their fathers, sons, brothers or partners, there is likely to be a disproportionate (BAME) WOMEN, impact on ethnic minorities. MENTAL HEALTH Black/Black British Women’s Mental Health AND COVID-19 The RDU reported that in 2014, 29% of Black/Black British women experienced a common mental Introduction disorder in the past week, 28.7% of women from a Women make up over half (50.8%) of the resident Mixed Other background reported the same. That’s population of England and Wales and at the last a higher rate than for White British women or Other Census, 13.9% or 3.9 million of these women were White women – 21% and 16% respectively. With no from a Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) campaign to improve the mental health of BAME background. Data from the latest Annual Population women in recent memory, there is no reason to Survey (Jan – Dec 2019) shows that BAME women believe that there has been any improvement since currently make up 16% of the female working age the data was collected in 2014. In fact, these population of England and Wales. White women percentages have probably increased with the make up the remaining 84%. It is worth noting that additional stressors created by the current crisis. BAME men currently make up 15% of the male working age population. 6.1% of NHS workers are It is well documented that many women from the Black/Black British despite Windrush generation came to the UK in the 1950’s making up only 3.4% of the and 1960’s to work in the NHS, and that BAME women are overrepresented in health and social- working age population.