THE JEWS of BATH Malcolm Brown and Judith Samuel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arquitectos Del Engaño

Arquitectos del Engaño Version original en Ingles CONTENIDO Explicaciones introductorias 4 1. Trance de consenso 6 Los mitos como base de poder 8 Gagarin nunca estuvo en el espacio 12 2. La oscura historia de los Caballeros Templarios 15 El origen de los Caballeros Templarios 17 La gran influencia de los Caballeros Templarios 18 Felipe IV contraataca 19 La maldición del gran maestre 22 El descubrimiento de Rennes-le-Chateau 23 3. El ascenso de la masonería 25 Comienza la infiltración 28 Las sociedades secretas se apoderan de los gremios de artesanos 31 El desarrollo del sistema masónico 35 Los grados mas altos 40 Otros ritos masónicos 42 Los símbolos 45 Magia masónica 54 Ideología masónica 62 4. El potente ámbito financiero 65 El interés como arma 67 Esclavitud económica 74 5. El poder global de la francmasonería 77 La francmasonería y la política 77 Los Illuminati 80 Estamos gobernados por los masones 85 Estados Unidos - La base executiva masónica 88 Harry Shippe Truman 95 El caso de Kissinger 99 Planos siniestros 101 La expansión de la masonería 104 P2 - La secta masónica mas infame 105 El Club 45 o "La logia roja de Viena" 114 La influencia masónica en Suecia 116 Los Carbonarios 117 La resistencia contra la francmasonería 119 El mundo masónico 127 6. La naturaleza roja i sangrante de la masonería 132 Los antecedentes históricos del Gran Oriente 133 La justicia de los masones 137 La corrupción masónica 141 La destrucción de Rusia 142 El soporte sanguinario de los comunistas 148 La aportación masónica en la Rusia Soviética 154 La lucha de Stalin contra la francmasonería 156 Los archivos secretos masónicos 157 La influencia oculta 158 7. -

Masonic Token

L*G*4 fa MASONIC TOKEN. WHEREBY ONE BROTHER MAY KNOW ANOTHER. VoLUME 5. PORTLAND, ME., MAY 15, 1913- No. 24. discharged. He reported that he had caused District Deputy Grand Masters. Published quarterly by Stephen Berry Co., $500 to be sent to the flood sufferers in Ohio. Districts. No. 37 Plum Street, Portland, Maine 1 Harry B. Holmes, Presque Isle. The address was received with applause. Twelve cts. per year in advance. 2 Wheeler C. Hawkes, Eastport. He presented the reports of the District 3 Joseph F. Leighton, Milbridge. Established March, 1867. - - 46th Year. Deputy Grand Masters and other papers, 4 Thomas C. Stanley, Brooklin. 5 Harry A. Fowles, La Grange. which were referred to appropriate com 6 Ralph W. Moore, Hampden. Advertisements $4.00 per inch, or $3.00 for half an incli for one year. mittees. 7 Elihu D. Chase, Unity. The Grand Treasurer and Grand Secre 8 Charles Kneeland, Stockton Springs. No advertisement received unless the advertiser, or some member of the firm, is a Freemason in tary made their annual reports. 9 Charles A. Wilson, Camden. good standing. 10 Wilbur F. Cate, Dresden. Reports of committees were made and ac 11 Charles R. Getchell. Hallowell. cepted. 12 Moses A. Gordon, Mt. Vernon. The Pear Tree. At 11:30 the Grand Lodge called off until 13 Ernest C. Butler, Skowhegan. 14 Edward L. White, Bowdoinham. 2 o’clock in the afternoon. When winter, like some evil dream, 15 John N. Foye, Canton. That cheerful morning puts to flight, 16 Davis G. Lovejoy, Bethel. Gives place to spring’s divine delight, Tuesday Afternoon., May 6th. -

BOARD of DEPUTIES of BRITISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 1944.Pdf

THE LONDON COMMITTEE OF DEPUTIES OF THE BRITISH JEWS (iFOUNDED IN 1760) GENERALLY KNOWN AS THE BOARD OF DEPUTIES OF BRITISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 1944 WOBURN HOUSE UPPER WOBURN PLACE LONDON, W.C.I 1945 .4-2. fd*׳American Jewish Comm LiBKARY FORM OF BEQUEST I bequeath to the LONDON COMMITTEE OF DEPUTIES OF THE BRITISH JEWS (generally known as the Board of Deputies of British Jews) the sum of £ free of duty, to be applied to the general purposes of the said Board and the receipt of the Treasurer for the time being of the said Board shall be a sufficient discharge for the same. Contents List of Officers of the Board .. .. 2 List of Former Presidents .. .. .. 3 List of Congregations and Institutions represented on the Board .. .... .. 4 Committees .. .. .. .. .. ..10 Annual Report—Introduction .. .. 13 Administrative . .. .. 14 Executive Committee .. .. .. ..15 Aliens Committee .. .. .. .. 18 Education Committee . .. .. 20 Finance Committee . .. 21 Jewish Defence Committee . .. 21 Law, Parliamentary and General Purposes Committee . 24 Palestine Committee .. .. .. 28 Foreign Affairs Committee . .. .. ... 30 Accounts 42 C . 4 a פ) 3 ' P, . (OffuiTS 01 tt!t iBaarft President: PROFESSOR S. BRODETSKY Vice-Presidents : DR. ISRAEL FELDMAN PROFESSOR SAMSON WRIGHT Treasurer : M. GORDON LIVERMAN, J,P. Hon. Auditors : JOSEPH MELLER, O.B.E. THE RT. HON. LORD SWAYTHLING Solicitor : CHARLES H. L. EMANUEL, M.A. Auditors : MESSRS. JOHN DIAMOND & Co. Secretary : A. G. BROTMAN, B.SC. All communications should be addressed to THE SECRETARY at:— Woburn House, Upper Woburn Place, London, W.C.I Telephone : EUSton 3952-3 Telegraphic Address : Deputies, Kincross, London Cables : Deputies, London 2 Past $xmbmt% 0f tht Uoati 1760 BENJAMIN MENDES DA COSTA 1766 JOSEPH SALVADOR 1778 JOSEPH SALVADOR 1789 MOSES ISAAC LEVY 1800-1812 . -

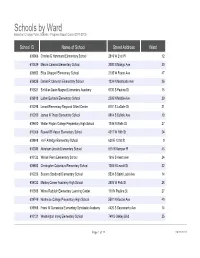

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

January 2021

ESTMINSTER Volume XII No.1 UARTERLY January 2021 A Jewish society wedding c.1892 Anglo-Jewish High Society The Philippines and the Holocaust The Children Smuggler ‘The Little Doctor’ From the Rabbi ‘Woe is me, perhaps because I have have identified; they suggest that, as the sinned, the world around me is being Festival itself marks increased darkness, darkened and returning to its state of let the candles reflect this reality too. chaos and confusion; this then is the Remove one each day, starting with the kind of death to which I have been eighth. The view of the School of Hillel sentenced from Heaven!’ So he began may also acknowledge that the world is keeping an eight-day fast. getting darker, but the ritual response is the opposite. When the world gets darker But as he observed the winter solstice we bring more light. and noted the day getting increasingly longer, he said, ‘This is the world’s So let us pay respect to both views. course’, and he set forth to keep an eight- Together we have the strength in our day festival. community to acknowledge the darkness in the world, and also to bring more light. (Adapted from the Babylonian Talmud, Many of us in the last year have stepped tractate Avodah Zara, page 8a.) up to contact and care for other members of our community, and we have benefited Together we have the from the resulting conversations and How do we respond to increased relations. We have found new creativity darkness? In Franz Kafka’s short story, strength in our to ensure our togetherness, building Before the Law, a man spends his whole community to special High Holy Days. -

The Position of the Moroccan Jewish Community Within the Anglo- Moroccan Diplomatic Relations from 1480 to 1886

The Position of the Moroccan Jewish community within the Anglo- Moroccan Diplomatic Relations from 1480 to 1886 A presentation made by Mohammed Belmahi, KCFO, former Moroccan Ambassador to London (1999-2009), upon the invitation of the Rotary Club of London, on Monday 11th. May 2015, at the Chesterfield hotel, 35 Charles Street, Mayfair. [email protected] The Kingdom of Morocco has always considered its Jewish community as an integral part of its social, cultural, economic and political fabric. The Moroccan Constitution of 17 June 2011 states in its Preamble the following: "[The Kingdom of Morocco's] unity is forged by the convergence of its Arab-Islamic, Berber and Saharan-Hassanic components, nourished and enriched by its African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean influences." Both at home and abroad, this community has enjoyed the trust, protection and support from the Kingdom's sovereigns. The Jews have in return contributed in the making of a multicultural and religiously diversified Moroccan society. Their craftsmanship, intellectual skills and international trading networks have helped boost the Moroccan economy. Therefore, Moroccan rulers have, throughout history, kept appointing prominent Moroccan Jews to high government positions such as political advisors, ministers, ambassadors, envoys, official trade representatives, or customs-duty and tax collectors. We choose to review this historical reality and examine it from the specific angle of the Anglo-Moroccan diplomatic relations going 800 years back in time. Such a long history permits us to make a deeper appraisal of the Moroccan Jews' position within these relations. Furthermore, our historical investigations are faced with no dearth of source- material, even when looking for data from as far back as the Sixteenth Century, when a continuous diplomatic relationship began between Morocco and England.(1) We will try to appraise this positioning by analysing a set of events and cases depicting Moroccan Jews during four centuries of Anglo-Moroccan relations, from 1480 to 1886. -

Anglo-Jewry's Experience of Secondary Education

Anglo-Jewry’s Experience of Secondary Education from the 1830s until 1920 Emma Tanya Harris A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements For award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies University College London London 2007 1 UMI Number: U592088 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592088 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract of Thesis This thesis examines the birth of secondary education for Jews in England, focusing on the middle classes as defined in the text. This study explores various types of secondary education that are categorised under one of two generic terms - Jewish secondary education or secondary education for Jews. The former describes institutions, offered by individual Jews, which provided a blend of religious and/or secular education. The latter focuses on non-Jewish schools which accepted Jews (and some which did not but were, nevertheless, attended by Jews). Whilst this work emphasises London and its environs, other areas of Jewish residence, both major and minor, are also investigated. -

SCOTT HOUSE SCOTT HOUSE 147 Church Road, Combe Down, Bath, Somerset, BA2 5JN

SCOTT HOUSE SCOTT HOUSE 147 Church Road, Combe Down, Bath, Somerset, BA2 5JN A MAGNIFICENT DETACHED REGENCY HOUSE SITUATED IN A HIGHLY SOUGHT AFTER LOCATION. ACCOMMODATION Reception hall, drawing room, dining room, basement, kitchen / breakfast room, family room, study, utility room, sitting / ground floor guest bedroom, shower room. First floor, principal bedroom, 5 further bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, laundry. OUTSIDE Driveway, double carport, landscaped front and rear gardens. Grade II listed DESCRIPTION Scott House is an imposing detached Regency house, with a handsome façade. Constructed of mellow Bath stone elevations under a tiled roof, the property is listed Grade II as being of architectural or historical interest. Scott House is a fine family house and has well proportioned accommodation arranged over two floors. The property has been very well maintained over the years and has been significantly enhanced in recent times. The entire property is presented in excellent decorative order. Fine architectural details typical of the period sit very well alongside contemporary fixtures and furnishings. Upon entering there is a well proportioned and inviting reception hall with open fire place. To the left is a dual aspect drawing room, also with fireplace and cornicing. Of particular note is the spectacular dining room measuring over 29 feet in length, with wooden floors and a fireplace. The basement is accessed from the dining room. Double doors lead into a well-appointed kitchen / breakfast room. There is a further sitting room overlooking the gardens which can also provide guest bedroom accommodation. In addition there is a shower room, study, a tv / family room and utility room at ground floor level. -

ARCHAEOLOGY. Villa at Combe Down, Near Bath, in the Middle Of

3Dt)ition0 to tbe Museum* From January 1st to October 12th (Council Day), 1917. I. ARCHAEOLOGY. (1). Stone Implements. FLINT scraper of Neolithic type and another flint imple- ment, from near the Vimy Ridge, Artois (2 miles behind the firing-line before the advance of the Canadians in April, 1917).—Deposited by Mr. Claude W. Gray. (2). Other Archaeological Remains. Small cross of bronze, perforated at the end of the upper arm and broken off at the other end rudely engraved on ; both faces height ins. Probably XIV-XV Century. ; 3tV Found about 1912 in the foundation of a now demolished cottage, in Langport Road, Somerton.—Presented by Mr. J. Lock. Angel-corbel, carved in oak, probably from Somerton Church.—Presented by Mr. J. C. M. Hall-Stephenson. Glazed tile, 5§ins. by Ifins., from the Bishop's Palace, Wells, 1880 ; XIII Century.—Presented by Mrs. Valentine. A few small bronze objects, including bosses, a nail-cleaner and a finger-ring ; one or two fragments of iron ; a bead of fused glass fragments of Samian pottery, of ; two pieces painted plaster, and a few tesserae. Found at the Roman Villa at Combe Down, near Bath, in the middle of last cen- tury. 1—Presented by Mr. G. E. Cruickshank. " 1. See Scarth's Aquae Solis," pp. 115-118. Most of the Combe Down " finds " are exhibited in the Bath Museum. The coins from Combe Down, presented by Mr. Cruickshank, will be recorded in the Proceedings, vol. lxiv, 1918. — Additions to the Museum. xxxvii Chimney-piece, or over-mantel, of Ham Hill stone, length 8ft. -

JBG Cottage History and Occupants 2

The Co'age: History and Occupants Descripon The co'age is situated to the right of the entrance gates, in the south west corner of the Jewish Burial Ground, forming part of the boundary with Greendown Place. It is a single storey, one room rectangular structure approximately 3.7m by 2.9m constructed of ooliDc limestone walls and a pitched roof covered with panDles. The co'age is entered through a plank door on the north gable end and there is a two/two sash window on the western wall fronDng Greendown Place. Internally, a plain stone surround to the fireplace remains on the eastern wall, to the right of a blocked up doorway/window. It is structurally stable but a shell. The footprint of the co'age has changed over the last two hundred years as evidence by historic maps (see below). Date On 8th April 1812, a thousand year lease on a narrow strip of “ground and demise” that was part of an adjacent Quarry, was agreed between a local Quarry owner and four members of the Bath Jewish community. The lease is preserved in the Bath Record Office and has been examined and transcribed by the Friends of the Burial Ground. It contains several references to the “land and demise”. This is evidence the co'age predates the Burial Ground and it is possible that the “de- mise” was already rented to a Quarryman. Func8on Religious FuncDon It has been assumed that the co'age had a Jewish religious funcDon. The Historic England LisDng comments that “The cemetery is notable for the survival of its Ohel (chapel)”. -

Combe Down Tunnel Midford Castle Dundas Aqueduct Canal Path

A Cross the River Avon onto Fieldings Lane. H Passing (or stopping at) the potential Please walk your bike across the bridge lunch spot at Brassknocker Basin and give way to pedestrians. café & campsite, Angelfish Restaurant, the Somerset Coal Canal (now used for B Opposite the Roman man artwork is the moorings) and Bath and Dundas Canal entrance to Bloomfield Road Open Space, Company (where you can hire canoes) from here you can pop into The Bear, great you will then cross over the canal beside if you fancy a coffee and cake stop. Dundas Aqueduct. *1 mile to the Odd Down Cycle Circuit (up steep hill – Bloomfield Road) DUNDAS AQUEDUCT Visit bathnes.gov.uk/gobybike An impressive grade 1 listed structure built C The ex-railway Devonshire Tunnel is ¼ from Bath stone in 1800, it carries the Kennet mile (408m) long and named after one & Avon Canal over the River Avon. The main of the roads that it lies beneath. arch has Doric pilasters and balustrades at each end. This was the first canal structure Two Tunnels D The second, longer Victorian tunnel is to be designated as a Scheduled Ancient Combe Down, which at 1.03 miles (1672m) Monument in 1951. is the longest cycling tunnel in the UK. I In front of The George at Bathampton On exiting the tunnels continue over E is a beautiful spot for a picnic, or grab the reservoir – look up hill to the right Greenway some family-friendly food at the pub. to see Midford Castle. Sometimes there is a barge selling ice MIDFORD CASTLE cream. -

Heredom, Volumes 1–26, 1992–2018 Prepared by S

Combined Index Heredom, Volumes 1–26, 1992–2018 Prepared by S. Brent Morris, 33°, G\C\ Numbers 29°. See Kt of St Andrew Sprengseysen (1788) 9:259 1°. See Entered Apprentice Degree 30°. See Kt Kadosh Abi, Abif, Abiff. See Hiram Abif. 2°. See Fellow Craft Degree 31°. See Inspector Inquisitor Abiathar, priest of Israel 25:448, 450, 3°. See Master Mason Degree 32°. See Master of the Royal Secret 456 4°. See Secret Master Degree 33°. See Inspector General, 33° Abiram (Abhiram, Abyram), password, 5°. See Perfect Master Degree (Sacred 43°, Sup Coun. See Forty-third Degree, Elect of Pérignan 2:93 Fire, NMJ) Sup Coun Abiram (Abhiram, Abyram, Akirop), 6°. See Confidential Secretary Degree assassin of Hiram Abif 1:69; (Master of the Brazen Serpent, A 72–74; 2:90, 92, 95n5; 3:38, 43, 45; NMJ) A and G, letters, interlaced 3:29, 33, 36; 4:113, 118; 6:153, 164; 25:492; 26:230, 7°. See Provost and Judge Degree 26:251 232. See also “Masonic Assassina- 8°. See Intendant of the Building Degree “A’ The Airts The Wind Can Blaw, Of,” tion of Akirop” (David and Solomon, NMJ) R. Burns 26:62 assassination of by Joabert 12:58, 60 9°. See Élu of the Nine Degree (Master Aachen Cathedral, Eye of Providence killed in cave under burning bush of the Temple, NMJ) 20:187 3:40 10,000 Famous Freemasons, W. Denslow AAONMS. See Shriners meaning and variations of name (1957) 23:115 Aaron (brother of Moses) 1:79n; 2:95n5; 3:46; 4:119 10°.