Crystal Structure of the Targeting Endonuclease of the Human LINE-1 Retrotransposon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restriction Endonucleases

Molecular Biology Problem Solver: A Laboratory Guide. Edited by Alan S. Gerstein Copyright © 2001 by Wiley-Liss, Inc. ISBNs: 0-471-37972-7 (Paper); 0-471-22390-5 (Electronic) 9 Restriction Endonucleases Derek Robinson, Paul R. Walsh, and Joseph A. Bonventre Background Information . 226 Which Restriction Enzymes Are Commercially Available? . 226 Why Are Some Enzymes More Expensive Than Others? . 227 What Can You Do to Reduce the Cost of Working with Restriction Enzymes? . 228 If You Could Select among Several Restriction Enzymes for Your Application, What Criteria Should You Consider to Make the Most Appropriate Choice? . 229 What Are the General Properties of Restriction Endonucleases? . 232 What Insight Is Provided by a Restriction Enzyme’s Quality Control Data? . 233 How Stable Are Restriction Enzymes? . 236 How Stable Are Diluted Restriction Enzymes? . 236 Simple Digests . 236 How Should You Set up a Simple Restriction Digest? . 236 Is It Wise to Modify the Suggested Reaction Conditions? . 237 Complex Restriction Digestions . 239 How Can a Substrate Affect the Restriction Digest? . 239 Should You Alter the Reaction Volume and DNA Concentration? . 241 Double Digests: Simultaneous or Sequential? . 242 225 Genomic Digests . 244 When Preparing Genomic DNA for Southern Blotting, How Can You Determine If Complete Digestion Has Been Obtained? . 244 What Are Your Options If You Must Create Additional Rare or Unique Restriction Sites? . 247 Troubleshooting . 255 What Can Cause a Simple Restriction Digest to Fail? . 255 The Volume of Enzyme in the Vial Appears Very Low. Did Leakage Occur during Shipment? . 259 The Enzyme Shipment Sat on the Shipping Dock for Two Days. -

Phosphate Steering by Flap Endonuclease 1 Promotes 50-flap Specificity and Incision to Prevent Genome Instability

ARTICLE Received 18 Jan 2017 | Accepted 5 May 2017 | Published 27 Jun 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms15855 OPEN Phosphate steering by Flap Endonuclease 1 promotes 50-flap specificity and incision to prevent genome instability Susan E. Tsutakawa1,*, Mark J. Thompson2,*, Andrew S. Arvai3,*, Alexander J. Neil4,*, Steven J. Shaw2, Sana I. Algasaier2, Jane C. Kim4, L. David Finger2, Emma Jardine2, Victoria J.B. Gotham2, Altaf H. Sarker5, Mai Z. Her1, Fahad Rashid6, Samir M. Hamdan6, Sergei M. Mirkin4, Jane A. Grasby2 & John A. Tainer1,7 DNA replication and repair enzyme Flap Endonuclease 1 (FEN1) is vital for genome integrity, and FEN1 mutations arise in multiple cancers. FEN1 precisely cleaves single-stranded (ss) 50-flaps one nucleotide into duplex (ds) DNA. Yet, how FEN1 selects for but does not incise the ss 50-flap was enigmatic. Here we combine crystallographic, biochemical and genetic analyses to show that two dsDNA binding sites set the 50polarity and to reveal unexpected control of the DNA phosphodiester backbone by electrostatic interactions. Via ‘phosphate steering’, basic residues energetically steer an inverted ss 50-flap through a gateway over FEN1’s active site and shift dsDNA for catalysis. Mutations of these residues cause an 18,000-fold reduction in catalytic rate in vitro and large-scale trinucleotide (GAA)n repeat expansions in vivo, implying failed phosphate-steering promotes an unanticipated lagging-strand template-switch mechanism during replication. Thus, phosphate steering is an unappreciated FEN1 function that enforces 50-flap specificity and catalysis, preventing genomic instability. 1 Molecular Biophysics and Integrated Bioimaging, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California 94720, USA. -

Structure and Function of Nucleases in DNA Repair: Shape, Grip and Blade of the DNA Scissors

Oncogene (2002) 21, 9022 – 9032 ª 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950 – 9232/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/onc Structure and function of nucleases in DNA repair: shape, grip and blade of the DNA scissors Tatsuya Nishino1 and Kosuke Morikawa*,1 1Department of Structural Biology, Biomolecular Engineering Research Institute (BERI), 6-2-3 Furuedai, Suita, Osaka 565-0874, Japan DNA nucleases catalyze the cleavage of phosphodiester mismatched nucleotides. They also recognize the bonds. These enzymes play crucial roles in various DNA replication or recombination intermediates to facilitate repair processes, which involve DNA replication, base the following reaction steps through the cleavage of excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, mismatch DNA strands (Table 1). repair, and double strand break repair. In recent years, Nucleases can be regarded as molecular scissors, new nucleases involved in various DNA repair processes which cleave phosphodiester bonds between the sugars have been reported, including the Mus81 : Mms4 (Eme1) and the phosphate moieties of DNA. They contain complex, which functions during the meiotic phase and conserved minimal motifs, which usually consist of the Artemis : DNA-PK complex, which processes a V(D)J acidic and basic residues forming the active site. recombination intermediate. Defects of these nucleases These active site residues coordinate catalytically cause genetic instability or severe immunodeficiency. essential divalent cations, such as magnesium, Thus, structural biology on various nuclease actions is calcium, manganese or zinc, as a cofactor. However, essential for the elucidation of the molecular mechanism the requirements for actual cleavage, such as the types of complex DNA repair machinery. Three-dimensional and the numbers of metals, are very complicated, but structural information of nucleases is also rapidly are not common among the nucleases. -

Endonuclease VIII

Product Specifications Y9080L Rev E Product Information Product Description: E.coli Endonuclease VIII functions as both an N-glycosylase (by excising oxidative base lesions) Endonuclease VIII and an AP lyase (by subsequently cleaving the phosphodiester backbone), leaving terminal phosphates at Part Number Y9080L the 5′ and 3′ ends. (1) Damaged bases removed by Endonuclease VIII include: urea, 5, 6- dihydroxythymine, Concentration 10,000 U/mL thymine glycol, 5-hydroxy-5- methylhydanton, uracil glycol, Unit Size 10,000 U 6-hydroxy-5, 6-dihydrothymine and methyltartronylurea (2,3). Storage Temperature -25⁰C to -15⁰C Product Specifications Y9080 Specific SS E. coli DNA Assay SDS Purity DS Exonuclease Activity Exonuclease Contamination Units Tested n/a n/a 10 100 100 >99% 770,513 <1.0% <1.0% <10 copies Specification Released Released Source of Protein: An E. coli strain which carries the cloned Endonuclease VIII gene. Unit Definition: 1 unit is defined as the amount of enzyme required to cleave 1 pmol of an oligonucleotide duplex containing a single AP site in 1 hour at 37°C. Molecular weight: 29,845 Daltons Quality Control Analysis: Unit Activity is measured using a 2-fold serial dilution method. Dilutions of enzyme were prepared in Endo VIII glycerol storage solution and added to 10 µL reactions containing a FAM-labeled, 35-base, duplex oligonucleotide, containing a single Uracil. [Note: substrate was pre-treated for 2 minutes with UDG to create an abasic site] Reactions were incubated 60 minutes at 37ºC, plunged on ice, denatured with N-N-dimethylformamide and analyzed by running and exposing to short-wave UV a 15% TBE-Urea acrylamide gel. -

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information (a) (b) Figure S1. Resistant (a) and sensitive (b) gene scores plotted against subsystems involved in cell regulation. The small circles represent the individual hits and the large circles represent the mean of each subsystem. Each individual score signifies the mean of 12 trials – three biological and four technical. The p-value was calculated as a two-tailed t-test and significance was determined using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure; false discovery rate was selected to be 0.1. Plots constructed using Pathway Tools, Omics Dashboard. Figure S2. Connectivity map displaying the predicted functional associations between the silver-resistant gene hits; disconnected gene hits not shown. The thicknesses of the lines indicate the degree of confidence prediction for the given interaction, based on fusion, co-occurrence, experimental and co-expression data. Figure produced using STRING (version 10.5) and a medium confidence score (approximate probability) of 0.4. Figure S3. Connectivity map displaying the predicted functional associations between the silver-sensitive gene hits; disconnected gene hits not shown. The thicknesses of the lines indicate the degree of confidence prediction for the given interaction, based on fusion, co-occurrence, experimental and co-expression data. Figure produced using STRING (version 10.5) and a medium confidence score (approximate probability) of 0.4. Figure S4. Metabolic overview of the pathways in Escherichia coli. The pathways involved in silver-resistance are coloured according to respective normalized score. Each individual score represents the mean of 12 trials – three biological and four technical. Amino acid – upward pointing triangle, carbohydrate – square, proteins – diamond, purines – vertical ellipse, cofactor – downward pointing triangle, tRNA – tee, and other – circle. -

Q 297 Suppl USE

The following supplement accompanies the article Atlantic salmon raised with diets low in long-chain polyunsaturated n-3 fatty acids in freshwater have a Mycoplasma dominated gut microbiota at sea Yang Jin, Inga Leena Angell, Simen Rød Sandve, Lars Gustav Snipen, Yngvar Olsen, Knut Rudi* *Corresponding author: [email protected] Aquaculture Environment Interactions 11: 31–39 (2019) Table S1. Composition of high- and low LC-PUFA diets. Stage Fresh water Sea water Feed type High LC-PUFA Low LC-PUFA Fish oil Initial fish weight (g) 0.2 0.4 1 5 15 30 50 0.2 0.4 1 5 15 30 50 80 200 Feed size (mm) 0.6 0.9 1.3 1.7 2.2 2.8 3.5 0.6 0.9 1.3 1.7 2.2 2.8 3.5 3.5 4.9 North Atlantic fishmeal (%) 41 40 40 40 40 30 30 41 40 40 40 40 30 30 35 25 Plant meals (%) 46 45 45 42 40 49 48 46 45 45 42 40 49 48 39 46 Additives (%) 3.3 3.2 3.2 3.5 3.3 3.4 3.9 3.3 3.2 3.2 3.5 3.3 3.4 3.9 2.6 3.3 North Atlantic fish oil (%) 9.9 12 12 15 16 17 18 0 0 0 0 0 1.2 1.2 23 26 Linseed oil (%) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6.8 8.1 8.1 9.7 11 10 11 0 0 Palm oil (%) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3.2 3.8 3.8 5.4 5.9 5.8 5.9 0 0 Protein (%) 56 55 55 51 49 47 47 56 55 55 51 49 47 47 44 41 Fat (%) 16 18 18 21 22 22 22 16 18 18 21 22 22 22 28 31 EPA+DHA (% diet) 2.2 2.4 2.4 2.9 3.1 3.1 3.1 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 4 4.2 Table S2. -

Restriction Endonuclease Map Variation and Gene

Heredity (1984) 52 (1), 103—112 1984. The Genetical Society of Great Britain RESTRICTIONENDONUCLEASE MAP VARIATION AND GENE ACTIVITY IN THE ADH REGION IN A POPULATION OF DROSOPHILA MELANOGASTER A. J. BIRLEY Department of Genetics, University of Birmingham, P.O. Box 363. Birmingham B 15217, England Received21.vii.83 SUMMARY Variation within a 12 kb region containing the Adh gene was studied in 16 highly inbred lines of independent extraction from a population of Drosophila melanogaster, "Texas". Out of a selection of 8 hexanucleotide specific restriction endonucleases, four restriction site and five DNA insertion/deletion variations were observed and the heterozygosity per nucleotide was 0004. Linkage dis- equilibrium between two restriction sites, considerably removed from and on either side of the Adh transcriptional unit, identified two major classes of chromosome or haplotype in the population. These two haplotypes were strongly associated with the capacity of lines to respond to the environment (genotype- environment interaction) in ADH activity. It was concluded that a control or regulatory polymorphism was present in the population in association with the Adh transcriptional unit. 1. INTRODUCTION The cloning of eukaryote DNA which contains the coding sequences of known genes potentially permits both a molecular analysis of the mechanism of gene expression as well as an assessment of the relationship, if any, between variations in coding and non-coding DNA of the different individuals in a population. The mapping of variations in nucleotide sequen- ces in cloned genomic or mitochondrial DNA with restriction endonucleases has now been used in a number of evolutionary studies of variation within populations and between species. -

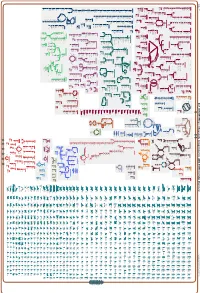

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

Authors: Pallavi Subhraveti Ron Caspi Peter Midford Peter D Karp An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Ingrid Keseler Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. Gcf_003855395Cyc: Shewanella livingstonensis LMG 19866 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. -

Biology of DNA Restriction THOMAS A

MICROBIOLOGICAL REVIEWS, June 1993, p. 434-450 Vol. 57, No. 2 0146-0749/93/020434-17$02.00/0 Copyright © 1993, American Society for Microbiology Biology of DNA Restriction THOMAS A. BICKLE'* AND DETLEV H. KRUGER2 Department ofMicrobiology, Biozentrum, Basel University, Klingelbergstrasse 70, CH-4056 Basel, Switzerland, 1 and Institute of Virology, Charite School ofMedicine, Humboldt University, D-0-1040 Berlin, Gernany2 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 434 TYPE I R-M SYSTEMS ........................................................................ 434 Type I Systems Form Families of Related Enzymes ...................................................................435 Structure of hsd Genes ........................................................................ 435 Evolution of DNA Sequence Recognition by Recombination between hsdS Genes .........................***436 Mutations Affecting Modification Activity........................................................................ 437 TYPE II R-M SYSTEMS........................................................................ 437 Evolutionary Aspects ........................................................................ 437 Control of Expression of Type II RM Genes .....................................................438 Cytosine Can Be Methylated on Either C-5 Or NA: Consequences for Mutagenesis...............438 Type II Restriction Endonucleases That Require Two Recognition Sites for Cleavage.439 What Is the Function of Type IIS Enzymes.440 -

Materials and Methods for the Alteration of Enzyme and Acetyl Coa Levels in Plants Basil J

Iowa State University Patents Iowa State University Research Foundation, Inc. 4-28-2009 Materials and methods for the alteration of enzyme and acetyl CoA levels in plants Basil J. Nikolau Iowa State University, [email protected] Eve S. Wurtele Iowa State University, [email protected] David J. Oliver Iowa State University, [email protected] Patrick S. Schnable Iowa State University, [email protected] Tsui-Jung Wen Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/patents Part of the Agriculture Commons, Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons, Biochemistry Commons, Botany Commons, Developmental Biology Commons, and the Molecular Biology Commons Recommended Citation Nikolau, Basil J.; Wurtele, Eve S.; Oliver, David J.; Schnable, Patrick S.; and Wen, Tsui-Jung, "Materials and methods for the alteration of enzyme and acetyl CoA levels in plants" (2009). Iowa State University Patents. 30. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/patents/30 This Patent is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Research Foundation, Inc. at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Iowa State University Patents by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Materials and methods for the alteration of enzyme and acetyl CoA levels in plants Abstract The present invention provides nucleic acid and amino acid sequences of acetyl CoA synthetase (ACS), plastidic pyruvate dehydrogenase (pPDH), ATP -

Table S1A. Enterococcus Faecium Phage 9181 Genome Organization and Features

Table S1A. Enterococcus faecium phage 9181 genome organization and features Phage 9181 genome annotation Feature Gene Gene Length Strand blastp Best-Hit cut-off Best-Hit % % % E-value Predicted Function ID Start Stop (0.001) Number Accession Gaps Identities Positives ORF1 15 959 945 + N-acetylmuramoyl-L- OJG47739 6 53 66 7.88E-98 N-acetylmuramoyl-L- alanine amidase alanine amidase Enterococcus hirae ORF2 1362 1601 240 + hypothetical protein ORF3 1605 1853 249 + hypothetical protein ORF4 1866 2048 183 + hypothetical protein ORF5 2045 2185 141 + hypothetical protein ORF6 2199 2483 285 + hypothetical protein ORF7 2496 2906 411 + hypothetical protein APU00246 0 45 68 2.70E-31 hypothetical protein EFP29_60 Enterococcus phage EF-P29 ORF8 3020 3178 159 + hypothetical protein WP_010749468 0 43 61 5.02E-04 hypothetical protein Enterococcus casseliflavus ORF9 3193 4158 966 + hypothetical protein YP_009036396 10 47 64 6.70E-70 hypothetical protein X878_0035 Enterococcus phage VD13 ORF10 4191 4730 540 + hypothetical protein ORF11 4727 5146 420 + hypothetical protein ORF12 5148 5348 201 + Enterococcus phage YP_009603964 3 58 70 8.41E-15 hypothetical protein IMEEF1 ORF13 6777 6971 195 + hypothetical protein ORF14 6976 7929 954 + hypothetical protein QBZ69248 1 50 70 7.56E-109 DNA primase Enterococcus phage vB_EfaS_Ef2.2 ORF15 7990 8268 279 + hypothetical protein ORF16 8268 9251 984 + hypothetical protein WP_088271390 10 36 53 1.69E-51 Rnl2 family RNA ligase Enterococcus wangshanyuanii ORF17 9253 9459 207 + hypothetical protein WP_002324739 0 65 76 6.90E-08 -

Mechanism of Action of Ribonuclease H Isolated from Avian Myeloblastosis Virus and Escherichia Coli* (RNA-Dependent DNA Polymerase/Processive Exonuclease/E

Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 70, No. 2, pp. 466-470, February 1973 Mechanism of Action of Ribonuclease H Isolated from Avian Myeloblastosis Virus and Escherichia coli* (RNA-dependent DNA polymerase/processive exonuclease/E. coli endonuclease) JONATHAN P. LEIS, IRA BERKOWER, AND JERARD HURWITZ Department of Developmental Biology and Cancer, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York 10461 Communicated by Leon A. Heppel, November 16, 1972 ABSTRACT Purified preparations of RNA-dependent nucleotide kinase (13) were prepared by Drs. R. Silber and DNA polymerase isolated from avian myeloblastosis virus V. G. Malathi. [,y-32P]ATP was purchased from New En- contain RNase H activity. Labeled ribohomopolymers are degraded in the presence of their complementary deoxyri- gland Nuclear; labeled polynucleotides and other nucleotides bopolymer, except [3HJpoly(U).poly(dA). The degradation were from Schwarz/Mann Research or Miles Laboratories, products formed from [3Hpoly(A) . poly(dT) were identified Inc. N-cyclohexyl-N'-3(4-methylmorpholinium)ethyl carbo- as oligonucleotides containing 3'-hydroxyl and 5'-phos- diimide p-toluene sulfonate was from Aldrich Chemical Co. pbate termini, while AMP was not detected. The nuclease has been characterized as a processive exonuclease that All other reagents were described (14). requires ends of poly(A) chains for activity. Exonucleolytic Assay for RNase H. Reaction mixtures (0.05 ml) containing attack occurs in both 5' to 3' and 3' to 5' directions. RNase H has also been purified from E. coli. This nu- 1 4mol of Tris - HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5 umol of MgC12, 0.3 jumol of clease degrades all homoribopolymers tested in the pres- dithioerythritol, 2 ,ug of albumin, 0.52 nmol of poly(dT), ence of their complementary deoxyribopolymers to yield 0.56 nmol of [3H]poly(A), and enzyme were incubated for 30 oligonucleotides with 5'-phosphate and 3'-hydroxyl ter- min at 380.