Keeping up with Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frans Timmermans Cc: Günther Oettinger, Jyrki Katainen, Karmenu Vella and Phil Hogan

Frans Timmermans Cc: Günther Oettinger, Jyrki Katainen, Karmenu Vella and Phil Hogan European Commission Rue de la Loi / Wetstraat 200 1049 Brussels 20th March 2018 Dear First Vice-President Timmermans, We are writing to you as civil society representatives (environmental NGOs, farmers, food movements, and animal welfare groups) regarding the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) reform, following recent details given in Commission presentations to the Council and the Parliament on its substance, in particular the common EU objectives. 1) We would like to recall that for the next CAP to be truly results-oriented, make effective and efficient use of EU taxpayers’ money, and respond to citizens’ demands to better protect our natural resources, ensure the welfare of farmed animals and ensure many and diversified farms, the EU objectives should be specific, measurable and time-bound so that progress towards them can be properly monitored.1 2) Unfortunately we are very concerned that the objectives will be very general and vague, which will make it very easy for Member States to systematically choose the least ambitious measures without facing adequate monitoring or control—as experienced with the last reform’s ‘greening’, which added complexity and completely failed to address the challenges facing the sector. 3) Furthermore, objectives focussed on increasing production—such as ‘food security’—are not only unjustified in the context of overproduction and overconsumption in Europe, especially of animal products, but also risk undermining other objectives on the long-term resilience of the sector, the environment, animal welfare, climate, human health and fair income for the smallest and most sustainable farms. -

Page 1 of 15 Mr Jean-Claude Juncker President European Commission Cc

Mr Jean-Claude Juncker President European Commission cc: Frans Timmermans, First Vice-President, in charge of Better Regulation, Inter-Institutional Relations, the Rule of Law and the Charter of Fundamental Rights Andrus Ansip, Vice-President for the Digital Single Market Jyrki Katainen, Vice-President for Jobs, Growth, Investment and Competitiveness Maroš Šefčovič, Vice-President for the Energy Union Vytenis Andriukaitis, Commissioner for Health and Food Safety Elžbieta Bieńkowska, Commissioner for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs Violeta Bulc, Commissioner for Transport Miguel Arias Cañete, Commissioner for Climate Action and Energy Corina Creţu, Commissioner for Regional Policy Carlos Moedas, Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation Cecilia Malmström, Commissioner for Trade Pierre Moscovici, Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, Taxation and Customs Tibor Navracsics, Commissioner for Education, Culture, Youth and Sport Günther Öttinger, Commissioner for Budget and Human Resources Marianne Thyssen, Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs, Skills and Labour Mobility Karmenu Vella, Commissioner for Environment, Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Margrethe Vestager, Commissioner for Competition Brussels, 16 June 2017 Re: Contribute to economic growth and climate change mitigation through a EU Cycling Strategy Dear President Juncker, With this letter, signed by leaders from businesses, public authorities and civil society, we call upon the European Commission to unlock the potential for creating jobs -

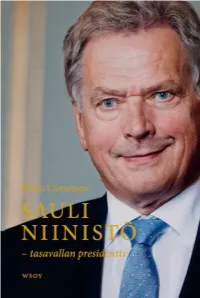

Sauli Niinistö – Tasavallan Presidentti Risto Uimonen Sauli Niinistö – Tasavallan Presidentti

sauli niinistö – tasavallan presidentti Risto Uimonen sauli niinistö – tasavallan presidentti werner söderström osakeyhtiö helsinki © Risto Uimonen ja WSOY 2018 ISBN 978-951-0-43107-8 Painettu EU:ssa Lapsenlapsilleni Lotalle (4 v.) ja Nupulle (3 v.) Sisällys 11 | LUKIJALLE 17 | SISÄÄNAJO UUTEEN TYÖHÖN Valtarakenteet murtuvat 19 Symboliikkaa eduskunnan portailla 24 Suomen vähävaltaisin presidentti 27 Presidentin tulkintaoikeus 35 Valtionpää arvojohtajana 43 Sammon ryöstö 49 55 | ULKOPOLITIIKAN JOHTAJA Idänsuhteiden painoarvo 57 Niinistö paljastaa karvansa 65 Juhannus Pietarissa 74 Kovaa substanssia yllin kyllin 81 Presidentti hakee ja löytää linjan 89 Ikävyyksiä itänaapurin kanssa 95 Tappio Luxemburgille 101 Islannin ilmavalvontakiista 108 Isännän ote lujittuu 117 Kylmä todellisuus vastassa 127 Yllätysmatka Sotshiin ja Kiovaan 137 Niinistöstä kypsyy ulkopoliitikko 142 151 | LISÄTURVAA ULKOMAILTA Poliittista Nato-retoriikkaa 153 Tekoja puheiden takana 164 Avunanto ja vastaanotto 175 Onttoja eurooppalaisia sitoumuksia 182 Suomalais-ruotsalaista veljeilyä 189 201 | VENÄJÄ – KOLMAS PILARI Suoraa puhetta Putinille 203 Puun ja kuoren välissä 215 Merkillinen vuoto itärajalla 223 Presidentit Punkaharjulla 228 235 | PRESIDENTTI JA EDUSKUNTA Tiivistä yhteydenpitoa valiokuntien kanssa 237 Taiten junailtu isäntämaasopimus 247 Puoluejohtajat hienovaraisessa ohjauksessa 258 269 | KOLME HALLITUSTA Pääministerit ulkopolitiikan johtajina 271 Korkean tason moitteita 279 Puheenjohtajan etuotto-oikeus 287 Keskustajohtajasta pääministeri 293 Täs siul on sellane -

THE JUNCKER COMMISSION: an Early Assessment

THE JUNCKER COMMISSION: An Early Assessment John Peterson University of Edinburgh Paper prepared for the 14th Biennial Conference of the EU Studies Association, Boston, 5-7th February 2015 DRAFT: Not for citation without permission Comments welcome [email protected] Abstract This paper offers an early evaluation of the European Commission under the Presidency of Jean-Claude Juncker, following his contested appointment as the so-called Spitzencandidat of the centre-right after the 2014 European Parliament (EP) election. It confronts questions including: What will effect will the manner of Juncker’s appointment have on the perceived legitimacy of the Commission? Will Juncker claim that the strength his mandate gives him license to run a highly Presidential, centralised Commission along the lines of his predecessor, José Manuel Barroso? Will Juncker continue to seek a modest and supportive role for the Commission (as Barroso did), or will his Commission embrace more ambitious new projects or seek to re-energise old ones? What effect will British opposition to Juncker’s appointment have on the United Kingdom’s efforts to renegotiate its status in the EU? The paper draws on a round of interviews with senior Commission officials conducted in early 2015 to try to identify patterns of both continuity and change in the Commission. Its central aim is to assess the meaning of answers to the questions posed above both for the Commission and EU as a whole in the remainder of the decade. What follows is the proverbial ‘thought piece’: an analysis that seeks to provoke debate and pose the right questions about its subject, as opposed to one that offers many answers. -

President High Representative

First Vice-President High Representative Frans Timmermans Federica Mogherini Better Regulation, Inter-Institutional High Representative of the Union Relations, the Rule of Law and the for Foreign Affairs and Security Poli- Charter of Fundamental Rights cy / Vice-President of the PRESIDENT Commission Vice-President JEAN-CLAUDE JUNCKER Vice-President Kristalina Georgieva Andrus Ansip Vice-President Vice-President Budget & Human Resources Digital Single Market Vice-President Alenka Bratušek Valdis Dombrovskis Jyrki Katainen Energy Union Euro & Social Dialogue Jobs, Growth, Investment and Competitiveness Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Vĕra Jourová Günther Oettinger Pierre Moscovici Marianne Thyssen Corina Creţu Johannes Hahn Justice, Consumers and Gender Digital Economy & Society Economic and Financial Affairs, Employment, Social Affairs, Regional Policy European Neighbourhood Policy Equality Taxation and Customs Skills and Labour Mobility & Enlargement Negotiations Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos Vytenis Andriukaitis Jonathan Hill Elżbieta Bieńkowska Miguel Arias Cañete Neven Mimica Financial Stability, Financial Services and Health & Food Safety Migration & Home Affairs Capital Markets Union Internal Market, Industry, Climate Action & Energy International Cooperation Entrepreneurship and SMEs & Development Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Margrethe Vestager Maroš Šefčovič Cecilia Malmström Karmenu Vella Competition Transport & Space Trade Environment, Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Tibor Navracsics Carlos Moedas Phil Hogan Christos Stylianides * The HRVP may ask the Commissioner Education, Culture, Youth and Research, Science Agriculture & Humanitarian Aid & (and other commissioners) to deputise Citizenship and Innovation Rural Development Crisis Management for her in areas related to Commission competence. -

3/2017 Suomalainen Klubi 1876–2017

Helsingin Suomalainen Klubi on kulttuuriklubi Klubilehti 3/2017 SUOMALAINEN KLUBI 1876–2017 Suomalaisen Klubin yhteiskunnallisiin vaikuttajiin on kuulunut mm. neljä presidenttiä Muita vaikuttajia on ikuistettu Pohjolakabinetin maalaukseen Antti Antero J.K. Paasikivi Martti Ahtisaari Waltteri Sipilä Maija Melanen ja Aarne Nopsanen maalaavat alkuperäistä Keskiviikkokerho-maalausta. Rudolf Waldén P.E. Svinhufvud Sauli Niinistö Jyrki Katainen Klubilehdelle: Klubi laajensi Suomen Kansan Marianne Heikkilä: Juncker Sähköistä Muistia Digi tulee, haluaa tehostaa Laaja Itsenäisyys100 oletko valmis päätöksentehoa -sivusto julkaistiin Juhla- sen tuloon s.14 s.24 vuoden kunniaksi s.32 Pääkirjoitus Myös neljän presidentin ja usean pääministerin Klubi n Klubilehti esittelee tässä numerossa Suomen yhteiskunnallisia vaikuttajia, jotka ovat tai ovat olleet myös Klubin jäseniä. Jyrki Vesikansa on kirjoittanut oivan kirjoituksen vahvoista suomalaisista vaikuttajista politiikan, talouden, puolustusvoimien ja journalisminkin alueella. Joukko on vaikuttava. Sen kärjessä on neljä presidenttiä, 2000-luvulta Martti Ahtisaari ja Sauli Niinistö sekä viime vuosituhannelta P. E. Svinhufvud ja J. K. Paasikivi, joista viimemainittu oli klubilainen jo pääministerinä. Muita pääministereitä ovat olleet T.M. Kivimäki, Risto Kuuskoski, Reino T. Lehto ja 1980-luvun lopulla Harri Holkeri. Tämän vuosituhannen kaksi presidentti-jäsentä todistavat elävästi Klubin pystyneen hyvin kantamaan ja kehittämään 140-vuotiaan klubimme alkuperäistä ajatusta toimia keskustelufoorumina. Se -

Seinäjoen Kokoomus • Sata Vuotta • 1919-2019

S E I N Ä J O E N KO KO O M U S SATA VUOTTA • 1919-2019 1919 S E I N Ä J O E N 2019 SEINÄJOEN KOKOOMUS • SATA VUOTTA • 1919-2019 Hyvä ystävä! Seinäjoen Kokoomus ry:llä on vuonna yritteliäisyys antaa mahdollisuudet 2019 tärkeä juhlavuosi: täytämme kehittää hyvinvointiamme. kunniakkaat 100 vuotta. Juhlistamme sitä juhlan ja kädessäsi olevan historiikin Haluan kiittää juhlan hetkellä lämpimästi merkeissä. Sataan vuoteen mahtuu lähes kaikkia Seinäjoen Kokoomuksessa koko itsenäisen Suomen historia ja taival. t o i m i v i a j a t o i m i n e i t a a k t i i v e j a . Vaikeuksien kautta on luotu hyvinvoin- Panoksenne yhteisten asioiden hoidossa tiyhteiskunta, jossa on moni asia hyvin. Se on ollut äärettömän tärkeää. Myöskään on vaatinut paitsi taistelua itsenäisyydestä ilman hyviä yhteistyökumppaneita, kuten myös paljon työtä ja viisaita päätöksiä, Seinäjoen kaupunkia, yhdistys ei voi joita on tehty yhdessä Suomea rakentaen. menestyä – teille myös kiitos. Erityisesti Kokoomus on ollut aina vastuullinen, h a l u a n v i e l ä k i i t t ä ä S e i n ä j o e n yksilöä kunnioittava arvopuolue, joka on Kokoomuksen kunniapuheenjohtajaa ja toiminut koko yhteiskunnan hyväksi niin juhlatoimikunnan puheenjohtaja Matti valtakunnallisesti, alueellisesti kuin Kuvajaa 100-vuotisjuhlamme valmistelun paikallisestikin. koordinoinnista ja historiikin kokoamises- ta. Seinäjoen Kokoomus on jäsenmäärältään suurin Pohjanmaan maakuntien alueella Vastuu alkaa siitä, että välittää. Tämän toimivista Kokoomuksen jäsenyhdistyk- Kokoomuksen taannoisen vaalisloganin sistä. Tänä päivänä jäseniä on noin 130. olen kokenut itselleni läheiseksi. Sen Yhdistys toimii aktiivisesti Kokoomuksen voimin jatketaan kohti satavuotiskautta Seinäjoen kunnallisjärjestössä yhteistyös- sopivasti uudistuen, hyviä perinteitä sä muiden paikallisten kokoomusyhdis- hylkäämättä. -

Forests Communication FE

Communication from the European Commission Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests. 2019, July 24th After last December’s announcement of the EU’s initiative to “step up European Action against Deforestation and Forest Degradation”, the European Commission has published yesterday its Communication “on stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests.” The document was presented by Frans Timmermans (first vice-president of the Commission) and Jyrki Katainen, (vice-president of the Commission and Commissioner for Jobs, Growth, Investment & Competitiveness) and praised both by Karmenu Vella (Commissioner for environment, maritime affairs and fisheries) and Neven Mimica (Commissioner for International Development). The Commission starts with the following assessment: Despite the EU’s recent positive trend in the growth of domestical forest cover, the global level still shows a bleak picture of continuing logging and rapidly disappearing forests, in particular regarding tropical primary forests. Indirectly, through consumption and trade, the EU is causing deforestation too as it represents around 10% of final consumption of products associated with deforestation. These products include palm oil, meat, soy, cocoa, rubber, timber and maize in the form of processed products or services. Thus the Communication expressed that deforestation and forest degradation pose a significant risk and challenge that needs to be tackled globally with more actions ”as despite all the efforts, we currently fall short on the conservation and sustainable use of forests”. Therefore the Commission calls for “a variety of regulatory and non-regulatory actions” and proposes a list of initial actions to reach its two-fold obJective of protecting the existing forests and to restore and increase the coverage worldwide. -

Join Europe's Leading Innovation Community

JOIN EUROPE’S LEADING INNOVATION COMMUNITY We provide decision makers in the worlds of research, industry and policy with new strategies, ideas and contacts to succeed. Academic members Industry partners Aalto University, Finland Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden ESADE Business School, Spain ETH Zurich, Switzerland European University Association Karolinska Institutet, Sweden KU Leuven, Belgium Medical University of Warsaw, Poland Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway Politecnico di Milano, Italy Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Sweden Sorbonne University, France The Association of Commonwealth Universities The Guild Trinity College Dublin, Ireland Public organisations TU Berlin, Germany University College London, UK University of Amsterdam, Netherlands University of Birmingham, UK University of Bologna, Italy University of Eastern Finland, Finland University of Luxembourg, Luxembourg University of Pisa, Italy University of Twente, Netherlands University of Warwick, UK Consortia and EU projects Testimonials Jerzy Buzek, Member and former President of the European Parliament; Chair of the ITRE Committee “Science|Business brings a modern approach towards Policymakers at S|B events: innovation.” Yvon Berland, President, Université Aix-Marseille EC Commissioners: ■ “The Network (…) is the only place where universities and Jyrki Katainen, Carlos Moedas, industries, at that level, can collaborate on both research Tibor Navracsics, Johannes and innovation. (…) No other network allows us to conduct Hahn substantive -

1 Final Manuscript of Chapter 5 in Nils Edling (Ed.): Changing Meanings Of

1 Final manuscript of chapter 5 in Nils Edling (ed.): Changing Meanings of the Welfare State: Histories of a Key Concept in the Nordic Countries. Berghahn Books, Oxford & New York 2019, pp. 225-275. The Conceptual History of the Welfare State in Finland Pauli Kettunen Reinhart Koselleck has taught us that one of the main characteristics of modern political concepts is their being ‘temporalized’. They were shaped as a means of governing the tension between ‘the space experience and the horizon of expectation’ that was constitutive of the modern notions of history and politics. The concepts became ‘instruments for the direction of historical movement’, which was often conceptualized as development or progress.1 From our current historical perspectives, the making of the welfare state easily appears as an important phase and stream of such a ‘historical movement’ in the Nordic countries. However, it was actually quite late that the concept of the welfare state played any significant part in the direction of this movement.2 In Finland, after the era of the expanding welfare state, the notion of the welfare state as a creation of a joint national project has strongly emerged. Such a notion seems to be shared in Finland more widely than in other Nordic countries, especially in Sweden, where a hard struggle opened up between the Social Democrats and the right-wing parties over ownership of the history of the welfare state.3 This may seem paradoxical, as still in the early 1990s Finnish social policy researchers could, with good reason, argue -

European Commission a Testimony by the President

European Commission 2004 – 2014 A Testimony by the President with selected documents JOSÉ MANUEL DURÃO BARROSO European Commission 2004 – 2014 A Testimony by the President with selected documents JOSÉ MANUEL DURÃO BARROSO Content European Commission 2004 – 2014: A testimony by the President ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������11 On Europe - Considerations on the present and the future of the European Union Humboldt University of Berlin, 8 May 2014 ������������������������������������������������������������������������� 63 Speeches Building a Partnership for Europe: Prosperity, Solidarity, Security 3 Vote of Approval, European Parliament Plenary Session Strasbourg, 21 July 2004 �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 91 Messina, 50 years on: turning the crisis to our advantage 50th Anniversary of the Messina Conference Messina, 4 June 2005 ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 99 France and Europe: a shared destiny French National Assembly Paris, 24 January 2006 �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������105 Seeing Through The Hallucinations Third Hugo Young Memorial Lecture London, 16 October 2006 �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������109 A stronger Europe for a successful globalisation -

The European Commission 2014-2019

Alessandro Di Mario September 2014 The European Commission 2014-2019 Practice Group(s): By Ignasi Guardans and Alessandro Di Mario Public Policy and Law I. Overview: A new structure European Regulatory / UK Regulatory President-elect Jean Claude Juncker announced on September 10 the allocation of responsibilities in his team and the way work will be organised in the European Commission once it takes office. The most important change, in terms of internal organization, refers to the new role of the Vice Presidents. In the Juncker Commission, there will be 6 Vice-Presidents in addition to the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy who is at the same time a Vice-President of the Commission. Vice-Presidents will lead project teams, sometimes called clusters (the terminology appears to have been dropped officially for now) steering and coordinating the work of a number of Commissioners. The compositions of these teams are decided for now, but that may change according to need and to possible new projects developing over time. This is supposed to ensure a dynamic interaction among Commissioners, breaking down silos. It remains to be seen if it simplifies or it actually complicates the legislative and decision making process. Vice Presidents have been charge with the role of: • Steering and coordinating work in their area of responsibility. This will involve bringing together several Commissioners and different parts of the Commission to shape coherent policies and deliver results. • Assessing how and whether proposed new initiatives fit with the focus of the Political Guidelines. As a general rule, now new initiative can be included in the Commission Work Programme or place it on the agenda of the College unless this is recommended to Juncker by one of the Vice-Presidents on the basis of sound arguments and a clear narrative that is coherent with the priority projects of the Political Guidelines.