Xfashion on the Move

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4H Horse Rules Show Book

Colorado 4-H Horse Show Rule Book LA1500K 2021 309997-HorseShowRuleBk-combo.indd 1 3/1/2021 10:16:08 AM ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The following members of the Colorado 4-H State Horse Advisory Rules Subcommittee assisted in the revision of the current Colorado 4-H Horse Show Rulebook: Angela Mannick (Elbert) Jodie Martin-Witt (Larimer) Tiffany Mead (Jefferson) Carmen Porter (Boulder) Tom Sharpe (Mesa) Jonathan Vrabec (El Paso) Lindsay Wadhams (Colorado State Fair) PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE PUBLICATION Requests for permission to reproduce any parts or all of this Colorado 4-H Youth-Development publication should be directed to: 4-H Publications Liaison State 4-H Office Colorado State University Cooperative Extension 4040 Campus Delivery Fort Collins, CO 80523-4040 Extension programs are available to all without discrimina- tion. To simplify technical terminology, trade names of products and equipment occasionally will be used. No endorsement of products named is intended nor is criticism implied of products not mentioned. Members are referred to the Colorado State Fair website for rules regarding entries for the state 4-H Horse Show held at the Colorado State Fair. 2020/2021 309997-HorseShowRuleBk-combo.indd 2 3/1/2021 10:16:08 AM TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................................................inside front cover Colorado State 4-H Horse Show Rules .................................................2 Use of the Name and Emblem of 4-H Club Work ...............................2 Horse Humane Policy Statement .........................................................2 -

Lolita PETRULION TRANSLATION of CULTURE-SPECIFIC ITEMS

VYTAUTAS MAGNUS UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF THE LITHUANIAN LANGUAGE Lolita PETRULION TRANSLATION OF CULTURE-SPECIFIC ITEMS FROM ENGLISH INTO LITHUANIAN AND RUSSIAN: THE CASE OF JOANNE HARRIS’ GOURMET NOVELS Doctoral Dissertation Humanities, Philology (04 H) Kaunas, 2015 UDK 81'25 Pe-254 This doctoral dissertation was written at Vytautas Magnus University in 2010-2014 Research supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ingrida Egl Žindžiuvien (Vytautas Magnus University, Humanities, Philology 04 H) ISBN 978-609-467-124-1 2 VYTAUTO DIDŽIOJO UNIVERSITETAS LIETUVI KALBOS INSTITUTAS Lolita PETRULION KULTROS ELEMENT VERTIMAS IŠ ANGL LIETUVI IR RUS KALBAS PAGAL JOANNE HARRIS GURMANIŠKUOSIUS ROMANUS Daktaro disertacija, Humanitariniai mokslai, filologija (04 H) Kaunas, 2015 3 Disertacija rengta 2010-2014 metais Vytauto Didžiojo universitete Mokslin vadov: prof. dr. Ingrida Egl Žindžiuvien (Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas, humanitariniai mokslai, filologija 04 H) 4 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my research supervisor Prof. Dr. Ingrida Egl Žindžiuvien for her excellent guidance and invaluable advices. I would like to thank her for being patient, tolerant and encouraging. It has been an honour and privilege to be her first PhD student. I would also like to thank the whole staff of Vytautas Magnus University, particularly the Department of English Philology, for both their professionalism and flexibility in providing high-quality PhD studies and managing the relevant procedures. Additional thanks go to the reviewers at the Department, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Irena Ragaišien and Prof. Dr. Habil. Milda Julija Danyt, for their valuable comments which enabled me to recognize the weaknesses in my thesis and make the necessary improvements. I would like to extend my sincere thanks to my home institution, Šiauliai University, especially to the Department of Foreign Languages Studies, who believed in my academic and scholarly qualities and motivated me in so many ways. -

1. Bareback Steer Riding 8. Barrel Racing 2. Boys Goat Tying 9

Saturday, November 7, 2015 6pm (Start of 2nd Rodeo) ORDER OF EVENTS 1. Bareback Steer Riding 8. Barrel Racing 2. Boys Goat Tying 9. Ribbon Roping 3. Girls Goat Tying 10. Saddle Bronc Steer Riding 4. Tie Down 11. Team Roping 5. Boys Breakaway 12. Pole Bending 6. Girls Breakaway 13. Bull Riding 7. Chute Doggin' BAREBACK STEER RIDING GIRLS GOAT TYING GIRLS BREAKAWAY 1 Ty Johnson 1 Anna Harris 1 Abi Greene 2 Ethan Lombardo 2 Sage Dunlap 2 Josie Hussey 3 Garrett Alliston 3 Kayla Earnhardt 3 Della Bird 4 Nace Boswell 4 Joanna Hammett 4 Brighton Bauman 5 Riley Kittle 5 Maggie Hodges 5 Daylee Buckner 6 Mason Hodge 6 Coty Baker 6 Makayla Back 7 Marcus Morse 7 Brighton Bauman 7 Makayla Osborne 8 Courtney Stalvey 8 Reagan Humphries 9 Olivia Wilks 9 Lynnsey Toole BOYS GOAT TYING 10 MaKayla Osborne 10 Grace Bryant 1 Seth Bennett 11 Brooklyn Hilliard 2 Tyler Lovering 12 Jessie McGaha 3 Jacob Crigger CHUTE DOGGIN' 4 Ty Hamilton 1 JC Bryan 5 Frog Bass TIE DOWN 2 Hunter White 6 Jerry Easler 1 Christopher Martin 3 Mason Hodge 7 Eli Covard 2 Cash Goble 4 Clayton Culligan 8 Garrett Manley 3 Riley Kittle 5 Jordan Hendrix 9 Wyatt Allen 4 Jerry Easler 6 Cody Vina 10 Drew Cluckey 5 Grant Henning 7 Briar Mabry 11 Briar Mabry 6 Lane Grubbs 8 Jacob Crigger 12 Hunter White 9 Lane Grubbs 10 Paul Shockley BOYS BREAKAWAY 1 Hagen Meeks 2 Colton Allen 3 Joey Denney 4 Hunter White 5 Jacob Crigger 6 Cooper Malone 7 Garrett Manley 8 Colby Dodson 9 Luke Lemaster Saturday, November 7, 2015 6pm (Start of 2nd Rodeo) BARREL RACING RIBBON ROPING / ROPER RIBBON ROPING / RUNNER -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

78Th Annual Comanche Rodeo Kicks Off June 7 and 8

www.thecomanchechief.com The Comanche Chief Thursday, June 6, 2019 Page 1C 778th8th AAnnualnnual CComancheomanche RRodeoodeo Comanche Rodeo in town this weekend Sponsored The 78th Annual Comanche Rodeo kicks off June 7 and 8. The rodeo is a UPRA and CPRA sanctioned event By and is being sponsored by TexasBank and the Comanche Roping Club Both nights the gates open at 6:00 p.m. with the mutton bustin’ for the youth beginning at 7:00 p.m. Tickets are $10 for adults and $5 for ages 6 to 12. Under 5 is free. Tickets may be purchased a online at PayPal.Me/ ComancheRopingClub, in the memo box specify your ticket purchase and they will check you at the gate. Tickets will be available at the gate as well. Friday and Saturday their will be a special performance at 8:00 p.m. by the Ladies Ranch Bronc Tour provided by the Texas Bronc Riders Association. After the rodeo on both nights a dance will be featured starting at 10:00 p.m. with live music. On Friday the Clint Allen Janisch Band will be performing and on Saturday the live music will be provided by Creed Fisher. On Saturday at 10:30 a.m. a rodeo parade will be held in downtown Comanche. After the parade stick around in downtown Comanche for ice cream, roping, stick horse races, vendor booths and food trucks. The parade and events following the parade are sponsored by the Comanche Chamber of Commerce. Look for the decorated windows and bunting around town. There is window decorating contest all over town that the businesses are participating in. -

Copa America a Chance for Brazil to Make Good

Australia recover to beat Brazil despite Marta’s landmark goal FRIDAY, JUNE 14, 2019 PAGE 12 India, Kiwis remain unbeaten at World Cup CRICKET WORLD CUP as rain rules in Trent Bridge PAGE 13 ENGLAND VS WEST INDIES Qatar, Australia Copa America a chance for Copa 2020 for Brazil to make good DPA BERLIN After falling short at 2014 World Cup, the hosts have opportunity in front of their own fans INJURED Neymar is miss- ing for hosts Brazil but Li- onel Messi leads Argentina in their quest for a first title in 26 years as South America’s Copa America tournament kicks off on Friday. Expectations are not only high for five-time world cham- President of the South American pions Brazil to be in the final in football’s governing body the Maracana on July 7 or for CONMEBOL, Paraguayan Alejandro Messi to end his title drought Dominguez, at a press conference in with the national team. Sao Paulo, Brazil on Thursday. (AFP) Reigning champions Chile are seeking to become the first AFP team in 72 years to win the SAO PAULO tournament for the third con- secutive year, while teams like AUSTRALIA have accepted Uruguay and Colombia will be an invitation to take part in hoping to make an impression. next year’s Copa America After 12 years without a alongside Asian champi- title, much is at stake for Bra- ons Qatar, who make their zil’s Selecao in front of their debut in the South American own fans. tournament this weekend, Full-back Filipe Luis said: CONMEBOL announced on “We never thought about be- Thursday. -

Sociology of Fashion: Order and Change

SO39CH09-Aspers ARI 24 June 2013 14:3 Sociology of Fashion: Order and Change Patrik Aspers1,2 and Fred´ eric´ Godart3 1Department of Sociology, Uppsala University, SE-751 26 Uppsala, Sweden 2Swedish School of Textiles, University of Bora˚s, SE-501 90 Bora˚s, Sweden; email: [email protected] 3Organisational Behaviour Department, INSEAD, 77305 Fontainebleau, France; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2013. 39:171–92 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on diffusion, distinction, identity, imitation, structure May 22, 2013 The Annual Review of Sociology is online at Abstract http://soc.annualreviews.org In this article, we synthesize and analyze sociological understanding Access provided by Emory University on 10/05/16. For personal use only. This article’s doi: Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2013.39:171-192. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org of fashion, with the main part of the review devoted to classical and 10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145526 recent sociological work. To further the development of this largely Copyright c 2013 by Annual Reviews. interdisciplinary field, we also highlight the key points of research in All rights reserved other disciplines. We define fashion as an unplanned process of re- current change against a backdrop of order in the public realm. We clarify this definition after tracing fashion’s origins and history. As a social phenomenon, fashion has been culturally and economically sig- nificant since the dawn of Modernity and has increased in importance with the emergence of mass markets, in terms of both production and consumption. Most research on this topic is concerned with dress, but we argue that there are no domain restrictions that should constrain fashion theories. -

Ancient and New Arabic Loans in Chadic Sergio Saldi

u L p A Ancient and University of New Arabic Loans Leipzig Papers on in Chadic Afrlca ! Languages and Literatures Sergio Saldi No.07 1999 University of Leipzig Papers on Africa Languages and Literatures Series No. 07 Ancient and New Arabic Loans in Chadic by Sergio Baldi Leipzig, 1999 ISBN: 3-932632-35-4 Orders should be addressed to: / Bestellungen an: Institut für Afrikanistik, Universität Leipzig Augustusplatz 9 D - 04109 Leipzig Phone: (0049)-(0)341-9737037 Fax: (0049)-(0)341-9737048 Em@il: [email protected] Internet: http://www. uni-leipzig.derifa/ulpa.htm University of Leipzie- Papers on Afrlca Languages and Literatures Serles Editor: H. Ekkehard Wolff Layout and Graphics: Toralf Richter Ancient and New Arabic Loans in Chadic Sergio Baldi Baldi, Ancient and New Arabic Loans in Chadic l Introduction1 Chadic languages have been influenced by Arabic at differents levels. Apart from Hausa which is a special case considering its diffusion on a very !arge area where sometimes it is spoken as a lingua franca, other Chadic languages have been in linguistic contact with Arabic, too. This paper illustrates the diffusion of Arabic loans among those Chadic languages for which it was possible to collect material through dictionaries and other sources listed at the end in References. As far as I know this is the first survey in Chadic languages on this topic, besides Hausa. Tue difficulty to do such work relates to the scarcity and sometimes inaccessability2) even ofpublished data. Also, works of only the last few decades are reliable. Tue languages taken into consideration are: Bidiya, Kotoko, Lame, Mafa, Mokilko, Musgu, Pero, Tangale and Tumak. -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

A Study of Stambeli in Digital Media

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 A Study of Stambeli in Digital Media Nneka Mogbo Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, African Studies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, Religion Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons A Study of Stambeli in Digital Media Nneka Mogbo Mounir Khélifa, Academic Director Dr. Raja Labadi, Advisor Wofford College Intercultural Studies Major Sidi Bou Saïd, Tunisia Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Tunisia and Italy: Politics and Religious Integration in the Mediterranean, SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 Abstract This research paper explores stambeli, a traditional spiritual music in Tunisia, by understanding its musical and spiritual components then identifying ways it is presented in digital media. Stambeli is shaped by pre-Islamic West African animist beliefs, spiritual healing and trances. The genre arrived in Tunisia when sub-Saharan Africans arrived in the north through slavery, migration or trade from present-day countries like Mauritania, Mali and Chad. Today, it is a geographic and cultural intersection of sub-Saharan, North and West African influences. Mogbo 2 Acknowledgements This paper would not be possible without the support of my advisor, Dr. Raja Labadi and the Spring 2019 SIT Tunisia academic staff: Mounir Khélifa, Alia Lamããne Ben Cheikh and Amina Brik. I am grateful to my host family for their hospitality and support throughout my academic semester and research period in Tunisia. I am especially grateful for my host sister, Rym Bouderbala, who helped me navigate translations. -

The Language of Fashion TITLES in the Bloomsbury Revelations Series

The Language of Fashion TITLES IN THE BLOOMSBURY REVELATIONS SERIES Aesthetic Theory, Theodor W. Adorno Being and Event, Alain Badiou On Religion, Karl Barth The Language of Fashion, Roland Barthes The Intelligence of Evil, Jean Baudrillard I and Thou, Martin Buber Never Give In!, Winston Churchill The Boer War, Winston Churchill The Second World War, Winston Churchill In Defence of Politics, Bernard Crick Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy, Manuel DeLanda A Thousand Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari Anti-Oedipus, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari Cinema I, Gilles Deleuze Cinema II, Gilles Deleuze Taking Rights Seriously, Ronald Dworkin Discourse on Free Will, Desiderius Erasmus and Martin Luther Education for Critical Consciousness, Paulo Freire Marx’s Concept of Man, Erich Fromm and Karl Marx To Have or To Be?, Erich Fromm Truth and Method, Hans Georg Gadamer All Men Are Brothers, Mohandas K. Gandhi Violence and the Sacred, Rene Girard The Essence of Truth, Martin Heidegger The Eclipse of Reason, Max Horkheimer The Language of the Third Reich, Victor Klemperer Rhythmanalysis, Henri Lefebvre After Virtue, Alasdair MacIntyre Time for Revolution, Antonio Negri Politics of Aesthetics, Jacques Ranciere Course in General Linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure An Actor Prepares, Constantin Stanislavski Building A Character, Constantin Stanislavski Creating A Role, Constantin Stanislavski Interrogating the Real, Slavoj Žižek Some titles are not available in North America. iv The Language of Fashion Roland Barthes Translated by Andy -

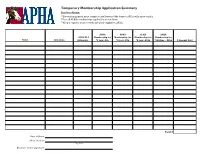

Temporary Membership Application Summary Instructions: **Show Management Must Complete and Forward This Form to APHA with Show Results

Temporary Membership Application Summary Instructions: **Show management must complete and forward this form to APHA with show results. **List all APHA memberships applied for at the show. **Keep a copy for your records and send original to APHA. APHA APHA APHA APHA APHA ID # Membership fee Membership fee Membership fee Membership fee Name City, State (if known) *1 year--$40 *3 year--$90 *5 year--$150 *Lifetime -- $500 $ Amount Paid Total $ Date of show: Show location City, State Show secretary signature: Horse Show Office Use Only: APHA Temporary Membership Application Show #: _____________________ Date: ________________________ Location: _____________________ American Paint Horse Association City, State P.O. Box 961023 u Fort Worth, Texas 76161-0023 (817) 834-APHA (2742) u Fax (817) 222-8489 COMPLETE APPLICATION IN FULL www.apha.com Omitting information will delay processing All exhibitors must be current APHA/AjPHA individual members in order to the eligible to show. For an AjPHA membership, please fill out a Temporary Youth Application. Proof of individual membership is required at time of showing. Membership Name: _____________________________________ Birth Date (Required for Youth 18 & Under): _____________________ Were you a member in the past? o Yes o No If yes, what was your member ID#: __________________________________ Address: ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ City: _______________________________________________________ State: ____________ Zip: _________________________ Phone: _____________________________________________________ Email: __________________________________________ Method of Payment: o Cash o Check/Money Order o VISA o MasterCard o American Express o $40 – Annual Membership o $90 – 3-year o $150 – 5-year o $500 – Lifetime Return to the show secretary with appropriate fees payable to APHA. All payments must be made in U.S.