Daily Casualties, Long-Term Wounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

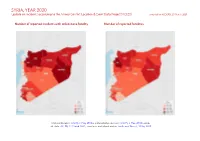

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 6187 930 2751 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 2 Battles 2465 1111 4206 Strategic developments 1517 2 2 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 1389 760 997 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 449 2 4 Riots 55 4 15 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 12062 2809 7975 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Spotlight on Global Jihad (February 27 – March 4, 2020)

( רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ"ל ןיעידומ כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ו רטל ו ר ט ןיעידומ ע ה ר Spotlight on Global Jihad February 27 – March 4, 2020 Highlights of the events This week, high-intensity battles took place in the Idlib region between the Syrian army and the forces supporting it (including the Lebanese Hezbollah) and the Headquarters for the Liberation of Al-Sham and the other rebel organizations. The battles centered on two areas. In the northeastern Idlib region, the rebel organizations managed to retake the city of Saraqeb (the most significant achievement to date). However, three days later, the Syrian army retook the city and the surrounding rural area (relatively easily) and regained control of the M-5 highway (the Damascus-Aleppo highway). At the same time, battles took place in the southern Idlib region. Both sides recorded local successes, but the general trend is to continue “gnawing away” at the areas controlled by the rebel organizations. Against the backdrop of the intensive fighting in the Idlib region, clashes between the Syrian army and the Turkish army escalated this week. On February 27, 2020, 33 Turkish soldiers were killed in a Syrian airstrike. In response, the Turkish army carried out extensive attacks against Syrian targets. Following the killing of the Turkish soldiers, the Turkish defense minister announced the start of Operation Spring Shield, a military operation against the Syrian army. Turkish President Erdoğan stressed that the operation was directed against targets of the Syrian regime and that Turkey was not targeting Russia and Iran. -

Recovery of Survivors of Improvised Explosive Devices and Explosive Remnants of War in Northeast Syria

Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction Volume 22 Issue 2 The Journal of Conventional Weapons Article 4 Destruction Issue 22.2 August 2018 Shattered Lives and Bodies: Recovery of Survivors of Improvised Explosive Devices and Explosive Remnants of War in Northeast Syria Médecins Sans Frontières MSF Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal Part of the Other Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Frontières, Médecins Sans (2018) "Shattered Lives and Bodies: Recovery of Survivors of Improvised Explosive Devices and Explosive Remnants of War in Northeast Syria," Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction: Vol. 22 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal/vol22/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction by an authorized editor of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frontières: Recovery of Survivors of IEDs and ERW in Northeast Syria Shattered Lives and Bodies: Recovery of Survivors of Improvised Explosive Devices and Explosive Remnants of War in Northeast Syria by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) n northeast Syria, fighting, airstrikes, and artillery shell- children were playing when one of them took an object from ing have led to the displacement of hundreds of thousands the ground and threw it. They did not know it was a mine. It Iof civilians from the cities of Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa, as exploded immediately. -

Deir Ezzor … Detention and Extortion of Civilians, and Oil Smuggling

Deir Ezzor … Detention and Extortion of Civilians, and Oil Smuggling Brief Report on Latest Updates in Some Deir Ezzor Areas Justice for Life Organization April 2019 Despite the control of Syrian government forces and Syria Democratic Forces over the entire province of Deir Ezzor after driving ISIS out, yet the civilians are still suffering from multiple problems as these forces are still committing violations against the civilians including detention, torture, and humiliation. The province is divided into two parts in terms of controlling power; the Syria government forces, supporting and affiliated militias along with foreign forces are controlling the cities, towns, and villages that are located in the south of Euphrates River, whereas the Syria Democratic Forces, with support of the US-led international coalition, control the areas located in the north of the river. This present report covers the latest developments in the two parts of Deir Ezzor in terms of the existing military powers, most prominent violations, fears of civilians, returning of IDPs, and the provided services. This report focuses on the cities of Deir Ezzor and Al Mayadin, in the south of the river, along with Al Kasra sub-district, the villages of Gharaneej, Al Kishkia, and Abu Hamam, in the north of the river. First: Syrian Government Forces Held Areas: 1- Deir Ezzor City It became a densely population city following the returning of hundreds of families towards the not destroyed neighborhoods such as Al Joura, Al Qusour, and Harabesh. The major reasons behind their returning to the city were the expensive rents, extortion practiced either by government forces, SDF, or opposition groups, and lack of humanitarian aid provided to them. -

Deir-Ez-Zor: Situation Overview and Sub-District Profiles Syria, June 2018

Deir-ez-Zor: Situation Overview and Sub-district Profiles Syria, June 2018 Background Methodology Since mid-2017, ongoing conflict has led to displacement from and within Overall, 112 locations in Deir-ez-Zor governorate were assessed between 4 and 11 Deir-ez-Zor governorate, totalling an estimated 230,000 persons from July to mid- June 2018 through remote Key Informant (KI) interviews, with a minimum of three December.1 While there had been de-escalation in some parts of the governorate KIs per assessed community and one KI per informal site. Different tools were in early 2018, renewed sustained conflict and related violence between Syrian used to assess communities and informal sites to identify population estimates Democratic Forces (SDF) and the group known as Islamic State of Iraq and the and multi-sectoral needs. Levant (ISIL) as well as sporadic clashes between SDF and Government of Syria Whilst efforts were made to cover as many locations as possible, assessed sites (GoS) are precipitating further displacement and exacerbating already-severe and communities were selected on the basis of their accessibility and should humanitarian conditions. Following previous assessments in February and April not be considered as a fully comprehensive list. Information should only be 2018, REACH recently conducted another rapid needs assessment to address considered as relevant to the time of data collection, given the dynamic situation information gaps and to provide an overview of the location and humanitarian in the governorate. Findings are not statistically representative and should be situation of different population groups. Assessed locations are clustered along considered as indicative only, particularly as they are aggregated across locations three main transects of the Euphrates and Khabour river (see Map 1). -

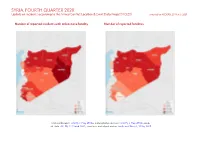

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 1539 195 615 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2018 to December 2020 2 Battles 650 308 1174 Violence against civilians 394 185 218 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 364 1 1 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 158 0 0 Riots 9 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 3114 689 2008 Disclaimer 7 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from December 2018 to December 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

Syria Crisis: Northeast Syria Situation Report No. 17 (1 – 20 October 2017) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices with the contribution of all sectors in the hubs and at the Whole of Syria (WoS) level. It covers the period from 1-20 October 2017. The next report will be issued on or around 15 November. Highlights The overall humanitarian and protection situation for civilians remains of high concern in Ar-Raqqa city, particularly explosive remnants of war (ERW) contamination. ERW mapping and clearance is required to ensure access for humanitarian partners and create a safe environment that is conducive for voluntary returns. While no civilians remain in the central neighborhoods of Ar-Raqqa city, some 2,000-3,000 individuals have returned to the eastern and western periphery of the city. The SDF have announced that no civilian returns will be permitted to the city for a period of three months. Those that attempt to return will be refused entry to facilitate ERW clearance. On 12 October, the Al-Malha screening point was subject to an ISIL suicide attac, highlighting the prevailing security risks and protection gaps at IDP screening sites. The humanitarian community continues to advocate with local authorities for the relocation of screening points to secure areas. Displacements from and within Deir-ez-Zor Governorate continued due to heavy fighting and airstrikes. Large influxes of IDPs from Deir-ez-Zor Governorate are straining existing capacities and services in IDP sites across north-eastern Syria resulting in increased humanitarain and protection needs. The overall protection situation for civilians remains of high concern across north-eastern Syria, with ISIL reportedly actively preventing civilians attempting to flee areas under its control in Deir-ez-Zor governorate. -

1 Week 1, 29 December

Week 1, 29 December – 4 January 2018 General developments & political & security situation 39,000 Killed in Syria in 2017: Around 39,000 people were killed in Syria in 2017, marking a decline from previous years, the SOHR reported. At least 10,507 of the fatalities were civilians, including some 2,109 children and 1,492 women, it said. The SOHR said the 2017 casualty figures were the second lowest annual rate since 2011. They signify a drop from last year’s numbers, which stood at 49,742. The conflict in Syria has killed more than 340,000 people since it started. President Vladimir Putin said on Thursday that Russia was the main force behind the defeat of the so-called Islamic State in Syria. Syrian president Bashar al-Assad issued a decree on Monday replacing his government’s ministers of information, defense and industry. Medical evacuations outside capital completed but fighting continues: Medical workers completed the evacuation of 29 critically ill civilians from the besieged Eastern Ghouta suburbs of the capital. Rebels pinned down in a small enclave southwest of Damascus began to evacuate the area as part of a surrender deal with the Syrian government. Rebels and their families started leaving Beit Jinn after Syrian troops and Iran- backed paramilitaries working alongside Druze militias encircled them. Some 300 insurgents and their families would be sent to Idlib and Daraa (at least 153 people, including 106 fighters, left Beit Jinn for the southern province of Daraa). The area around Beit Jinn is sensitive because of its proximity to the Israel-controlled Golan Heights. -

Health Response to the Situation in Deir-Ez-Zor

Health Response to the Situation in Deir-ez-Zor Report of a WHO assessment SEPTEMBER 2017 CONTENT Executive summary 3 Background 4 Displacement trends 5 Trauma care in northern Syria 6 WHO’s Emergency Medical Teams (EMT) Initiative: 6 Challenges 7 Situation assessment 8 Health care resources in Deir-ez-Zor governorate 8 Recommended actions 11 1. Enhance capacity of Al-Assad hospital 11 2. Organize evacuation pathways for wounded patients in and around Deir-ez-Zor 11 3. Reduce the patient load on Al-Assad hospital and secure advanced treatment 11 4. Establish standby surgical capacity in Abu Kamal or Hajin 11 5. Establish evacuation pathways to Abu Kamal or Hajin 12 6. Identify and organize evacuation pathways for the frontline north of Al Quesra. 12 General considerations 13 List of equipment 14 Annex 15 Health Response to the Situation in Deir-ez-Zor - September 2017 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large swathes of the northern Syrian governorate of Deir-ez-Zor have been under the control of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) since mid-2014. On 5 September 2017, the Government of Syria (GoS) and allied forces broke ISIL’s three-year siege on the government-held parts of the governorate’s capital city, also called Deir-ez- Zor. ISIL is becoming increasingly isolated as the GoS and allied forces advance on several fronts towards ISIL-held territory in the governorate, and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), backed by the US-led coalition, advance from the north. The intensity of clashes and airstrikes continues to result in civilian casualties, large numbers of internally displaced people (IDPs), and damaged or destroyed infrastructures including health care facilities. -

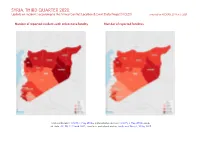

SYRIA, THIRD QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, THIRD QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, THIRD QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 1439 241 633 violence Development of conflict incidents from September 2018 to September Battles 543 232 747 2020 2 Violence against civilians 400 209 262 Strategic developments 394 0 0 Methodology 3 Protests 107 0 0 Conflict incidents per province 4 Riots 12 1 2 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 2895 683 1644 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Disclaimer 7 Development of conflict incidents from September 2018 to September 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, THIRD QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Deir Ezzor … Protests, Proliferation of Crime, and Soaring Prices

Deir Ezzor … Protests, Proliferation of Crime, and Soaring Prices A brief paper on the most prominent events in the province during the first half of the 2020 July 2020 Introduction Many events that have taken place in Deir Ezzor governorate since the beginning of 2020, some of which have had a direct and significant impact on the daily lives of the population, COVID-19 pandemic and the ban imposed on the movement of people, the repercussions of Caesar Act and the decline in the exchange rate of the Syrian pound have led to further decline in living conditions and emergence of demonstrations in different areas. These events prompted the Autonomous Administration to react, economically, raising the wages of employees of its institutions, and as for security, it tightened its security grip to block repeated demonstrations by threatening those participating and organizing demonstrations, while continuing the policy of running ahead and not listening to the demands of the demonstrators. Targeting the Autonomous Administration workers and activists has increased the already existing congestion among a number of villages, and the proliferation of weapons among residents has played a role in increasing fears of new societal explosions. The lack of intervention by the dominant forces to control security prompts local efforts to play a mediating role between the warring parties, as happened in a bloody fighting between two clans in the north of Deir Ezzor. Recent events have affected the activity of civil society organizations, where their activities have been banned for a period and many are reluctant to operate in some unstable areas, from a security perspective. -

Insecurity Grips Deir Ez-Zor

Empty paper for the cover photo www.stj-sy.org Insecurity Grips Deir ez-Zor: Locals Concerned Following a Series of Disturbing Murders In this joint report, Justice for Life (JFL) and Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) provide an extensive account of the murders of Sa’da al- Harmas, Hind al-Khdair, and Aboud Ali al-Mhaimeed. Page | 2 www.stj-sy.org Background The Islamic State (IS), locally known as Daesh, has been ramping up its activities in parts of Deir ez-Zor’s countryside and al-Hasakah’s southern areas, where the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) remain in power. In January and February 2021, assassinations perpetrated by IS sleeper cells increased, targeting civilians, including two local female officials of the Autonomous Administration and a local activist. In this report, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ), in cooperation with Justice for Life (JFL), provides the details and circumstances surrounding the murders of the Joint President of the Tal al-Shayer Town Council, Sa’da al-Harmas, and her deputy Hind al-Khdair. The bodies of the two women were retrieved on 22 January 2021, hours after a raid into their homes in Tal al-Shayer town, administratively affiliated to al-Dashisha district, south of al-Hasakah province. Eyewitnesses and relatives of the victims recounted that the two women were led out of their homes by force, kidnapped, shot, and killed by an IS-affiliated group who presented themselves as SDF intelligence personnel. IS claimed responsibility for the two murders on 24 January 2021, sending shock waves through the ranks of Autonomous Administration workers and the local community.