NVS 11-2-5 DM-Pho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory Pictures in a Time of Defeat: Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory pictures in a time of defeat: depicting war in the print and visual culture of late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18449 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. VICTORY PICTURES IN A TIME OF DEFEAT Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884-1901 Yin Hwang Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

Whose History and by Whom: an Analysis of the History of Taiwan In

WHOSE HISTORY AND BY WHOM: AN ANALYSIS OF THE HISTORY OF TAIWAN IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE PUBLISHED IN THE POSTWAR ERA by LIN-MIAO LU (Under the Direction of Joel Taxel) ABSTRACT Guided by the tenet of sociology of school knowledge, this study examines 38 Taiwanese children’s trade books that share an overarching theme of the history of Taiwan published after World War II to uncover whether the seemingly innocent texts for children convey particular messages, perspectives, and ideologies selected, preserved, and perpetuated by particular groups of people at specific historical time periods. By adopting the concept of selective tradition and theories of ideology and hegemony along with the analytic strategies of constant comparative analysis and iconography, the written texts and visual images of the children’s literature are relationally analyzed to determine what aspects of the history and whose ideologies and perspectives were selected (or neglected) and distributed in the literary format. Central to this analysis is the investigation and analysis of the interrelations between literary content and the issue of power. Closely related to the discussion of ideological peculiarities, historians’ research on the development of Taiwanese historiography also is considered in order to examine and analyze whether the literary products fall into two paradigms: the Chinese-centric paradigm (Chinese-centricism) and the Taiwanese-centric paradigm (Taiwanese-centricism). Analysis suggests a power-and-knowledge nexus that reflects contemporary ruling groups’ control in the domain of children’s narratives in which subordinate groups’ perspectives are minimalized, whereas powerful groups’ assumptions and beliefs prevail and are perpetuated as legitimized knowledge in society. -

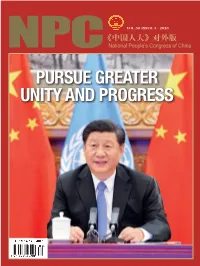

Pursue Greater Unity and Progress News Brief

VOL.50 ISSUE 3 · 2020 《中国人大》对外版 NPC National People’s Congress of China PURSUE GREATER UNITY AND pROGRESS NEWS BRIEF President Xi Jinping attends a video conference with United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres from Beijing on September 23. Liu Weibing 2 NATIONAL PEOPle’s CoNGRESS OF CHINA ISSUE 3 · 2020 3 6 Pursue greater unity and progress Contents UN’s 75th Anniversary CIFTIS: Global Services, Shared Prosperity National Medals and Honorary Titles 6 18 26 Pursue greater unity Global services, shared prosperity President Xi presents medals and progress to COVID-19 fighters 22 9 Shared progress and mutually Special Reports Make the world a better place beneficial cooperation for everyone 24 30 12 Accelerated development of trade in Work together to defeat COVID-19 Xi Jinping meets with UN services benefits the global economy and build a community with a shared Secretary-General António future for mankind Guterres 32 14 Promote peace and development China’s commitment to through parliamentary diplomacy multilateralism illustrated 4 NATIONAL PEOPle’s CoNGRESS OF CHINA 42 The final stretch Accelerated development of trade in 24 services benefits the global economy 36 Top legislator stresses soil protection ISSUE 3 · 2020 Fcous 38 Stop food waste with legislation, 34 crack down on eating shows Top legislature resolves HKSAR Leg- VOL.50 ISSUE 3 September 2020 Co vacancy concern Administrated by General Office of the Standing Poverty Alleviation Committee of National People’s Congress 36 Top legislator stresses soil protection Chief Editor: Wang Yang General Editorial 42 Office Address: 23 Xijiaominxiang, The final stretch Xicheng District, Beijing 37 100805, P.R.China Full implementation wildlife protection Tel: (86-10)5560-4181 law stressed (86-10)6309-8540 E-mail: [email protected] COVER: President Xi Jinping ad- ISSN 1674-3008 dresses a high-level meeting to CN 11-5683/D commemorate the 75th anniversary Price: RMB 35 of the United Nations via video link Edited by The People’s Congresses Journal on September 21. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement October 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 44 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 48 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 49 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 56 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 60 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

![军jūn Army / Military / Arms / CL:個/ |个/ [Ge4] Results Beginning with 军](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3960/j%C5%ABn-army-military-arms-cl-ge4-results-beginning-with-1103960.webp)

军jūn Army / Military / Arms / CL:個/ |个/ [Ge4] Results Beginning with 军

军 jūn army / military / arms / CL:個 / |个 / [ge4] Results beginning with 军 军 事 jūn shì military affairs / military matters / military 军队 jūn duì army / troops / CL:支 / [zhi1],個 / |个 / [ge4] 军 团 jūn tuán corps / legion 军 人 jūn rén serviceman / soldier / military personnel 军 官 jūn guān officer (military) 军 方 jūn fāng military 军 区 jūn qū geographical area of command / (PLA) military district 军 用 jūn yòng (for) military use / military application 军营 jūn yíng barracks / army camp 军 训 jūn xùn military practice, esp. for reservists or new recruits / military training as a (sometimes compulsory) subject in schools and colleges / drill 军 医 jūn yī military doctor 军 师 jūn shī (old) military counselor / (coll.) trusted adviser 军 委 jūn wěi Military Commission of the Communist Party Central Committee 军 校 jūn xiào military school / military academy 军舰 jūn jiàn warship / military naval vessel / CL:艘 / [sou1] 军 民 jūn mín army-civilian / military-masses / military-civilian 军衔 jūn xián army rank / military rank 军 士 jūn shì sergeant 军 工 jūn gōng [FR] industrie de guerre ; projet de travaux militaires 军 装 jūn zhuāng military uniform 军 火 jūn huǒ weapons and ammunition / munitions / arms 军 刀 jūn dāo military knife / saber 军 力 jūn lì military power 军 长 jūn zhǎng [FR] Corps d'armée 军阀 jūn fá military clique / junta / warlord 军 政 jūn zhèng army and government 军 演 jūn yǎn military exercises 军 服 jūn fú [FR] uniforme militaire 军 情 jūn qíng military intelligence 军 旅 jūn lu:3 army 军费 jūn fèi military expenditure 军 心 jūn xīn [FR] moral 军 备 jūn bèi (military) arms / armaments -

20180613113049 4678.Pdf

CHINA FOUNDATION FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION ANNUAL REPORT Focus on the Extreme Poor Assist to Realize National Strategy ABOUT US China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation, established in 1989, is a national public foundation registered with the Ministry of Civil Affairs. It was awarded with the National 5A Foundation by the Ministry of Civil Affairs in 2007 and 2013. It was first identi ed by the Ministry of Civil A airs as a charitable organization with public fund- raising quali cation in September 2016. OUR VISION Be the best trusted, the best expected and the best respected international philanthropy platform OUR MISSION Disseminate good and reduce poverty, help others to achieve their aims, and make the good more powerful OUR VALUES Service, Innovation, Transparency, Tenacity On December 4, The 4th World Internet Conference “Shared Dividends: Targeted Poverty Alleviation through the Internet” hosted by China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation was held in Wuzhen. Liu Yongfu, Director of the State Council Leading Group Offi ce of Poverty Alleviation and Development, attended the forum and made an important speech. CHINA FOUNDATION FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION ANNUAL REPORT By the end of 2017 CFPA had accumulatively raised poverty alleviation funds and materials of RMB 34.09 billion yuan Number of benefi ciaries in the impoverished condition and the disaster areas reached 33,280,700 person-time Zheng Wenkai, President of China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation The year of 2017 was a milestone year for the development of the socialism with Chinese characteristics. The 19th National Party Congress was successfully held and China has entered a new era and embarked on a new journey with a new attitude. -

Bandits and the State Unresolved Disputes in Southeast Asia

The Newsletter | No.78 | Autumn 2017 24 | The Review Bandits and the State If clothes make the man then we can say that the clothes of bandits came in all shapes and sizes. There was no such thing as the typical bandit, no one size fits all. Some bandits neatly fit Eric Hobsbawm’s formula for social bandits who robbed the rich and gave to the poor and who lived among and protected peasant communities. Others, and probably most, simply looked out for themselves, plundering both rich and poor. Some bandits were career professionals, but most were simply amateurs who took up banditry as a part-time job to supplement meagre legitimate earnings. While some bandits formed large permanent gangs, even armies numbering into the thousands, other gangs were ad hoc and small, usually only numbering in the tens or twenties. Most small gangs disbanded after a few heists. Many of the larger, more permanent gangs tended to operate in remote areas far away from the seats of government, but some gangs, usually the smaller impermanent ones, also operated in densely populated core areas. Although some bandits had political ambitions and received recognition and legitimacy from the state, most simply remained thugs and criminals throughout their careers. None of these categories, however, were mutually exclusive, as roles – like clothes – often changed according to circumstances. Reviewer: Robert Antony, Guangzhou University Reviewed title: who hailed from south China’s Qinzhou area in what is never became imperial bandits, but instead remained Bradley Camp Davis. 2017 now Guangxi province. A charismatic figure and skilful outlaws and wanted criminals. -

Bigger Brics, Larger Role

ISSUE 3 · 2017 《中国人大》对外版 National People’s Congress of China BIGGER BRICS, LARGER ROLE IN ITs sEcOND DEcADE, BRICS Is READY FOR A GREATER sHARE IN GLObAL GOVERNANcE President Xi Jinping (C) and other leaders of BRICS countries pose for a group photo during the 2017 President Xi Jinping presides over the BRICS Summit in Xiamen, south- Ninth BRICS Summit in Xiamen, Fujian east China’s Fujian Province, on Province, September 4. South African September 4. Zhang Duo President Jacob Zuma, Brazilian President Michel Temer, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Xiamen International Conference Modi attended the summit. Xie Huanchi and Exhibition Center VCG President Xi Jinping meets the press at the end of the Ninth BRICS Summit in Xiamen, Fujian Province, September 5. Hou Yu SPECIAL REPORT 6 Bigger BRICS, larger role Contents BRICS Summit Special Report 6 22 Bigger BRICS, larger role Zhang Dejiang visits Portugal, Poland and Serbia HK’s 20th Return Anniversary 26 Time-honored friendship 12 heralds future-oriented partnership President Xi Jinping’s speech at Focus the meeting celebrating the 20th anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to the motherland and the inau- 30 gural ceremony of the fifth-term China’s comprehensive moves HKSAR government in advancing rule of law 16 32 The tale of a city Laudable progress in advancing rule of law 4 NATIONAL PEOPLE’S CONGRESS OF CHINA NPC The tale of a city 16 43 China’s comprehensive moves On the wings of modernization 30 in advancing rule of law ISSUE 3 · 2017 Supervision Nationality -

Taiwán: De Provincia China a Colonia

Revista mexicana de estudios sobre la Cuenca del Pacífico Tercera Época • Volumen3 • Número 5 • Enero / Junio 200 9 • Colima, México Revista mexicana de estudios sobre la Cuenca del Pacífico Tercera Época • Volumen3 • Número5 • Enero/ Juniode 200 9 • Colima, México Dr. Fernando Alfonso Rivas Mira Comité editorial nacional Coordinador de la revista Dra . Mayrén Polanco Gaytán / Universidad de Colima, Lic. Ihovan Pineda Lara Facultad de Economía Asistente de coordinación de la revista Mt or. Alfredo Romero Castilla / UNAM, Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales Comité editorial internacional Dr. Juan González García / Universidad de Colima, CUEICP Dr. José Ernesto Rangel Delgado / Universidad de Colima Dr. Hadi Soesastro ( ) Dr. Pablo Wong González / Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, CIAD Sonora Center for Strategic and International Studies, Dr. Clemente Ruiz Durán / UNAM-Facultad de Economía Indonesia Dr. León Bendesky Bronstein / ERI Dr. Víctor López Villafañe / ITESM-Relaciones Dr. Pablo Bustelo Gómez Internacionales, Monterrey Universidad Complutense de Madrid, España Dr. Carlos Uscanga Prieto / UNAM-Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales Dr. Kim Won ho Profr. Omar Martínez Legorreta / Colegio Mexiquense Universidad Hankuk, Corea del Sur Dr. Ernesto Henry Turner Barragán / UAM-Azcapotzalco Departamento de Economía Dr. Mitsuhiro Kagami Dra. Marisela Connelly / El Colegio de México-Centro de Instituto de Economías en Desarrollo, Japón Estudios de Asia y África Universidad de Colima Cuerpo de árbitros Dra. Genevieve Marchini W. / Universidad de Guadalajara- MC Miguel Ángel Aguayo López Departamento de Estudios Internacionales. Especializada en Rector Economía Financiera en la región del Asia Pacífico Mtro. Alfonso Mercado García / El Colegio de México y El Dr. Ramón Cedillo Nakay Colegio de la Frontera Norte. -

Section 3 – Constitutionalism and the Wars with China and Russia

Section 3 – Constitutionalism and the wars with China and Russia Topic 58 – The struggle to revise the unequal treaties What strategies did Japan employ in order to renegotiate the unequal treaties signed with | 226 the Western powers during the final years of the shogunate? The problem of the unequal treaties The treaties that the shogunate signed with the Western powers in its final years were humiliating to the Japanese people due to the unequal terms they forced upon Japan. Firstly, any foreign national who committed a crime against a Japanese person was tried, not in a Japanese court, but in a consular court set up by the nation of the accused criminal.1 Secondly, Japan lost the right, just as many other Asian countries had, to set its own import tariffs. The Japanese people of the Meiji period yearned to end this legal discrimination imposed by the Western powers, and revision of the unequal treaties became Japan's foremost diplomatic priority. *1=The exclusive right held by foreign countries to try their own citizens in consular courts for crimes committed against Japanese people was referred to as the right of consular jurisdiction, which was a form of extraterritoriality. In 1872 (Meiji 5), the Iwakura Mission attempted to discuss the revision of the unequal treaties with the United States, but was rebuffed on the grounds that Japan had not reformed its legal system, particularly its criminal law. For this reason, Japan set aside the issue of consular jurisdiction and made recovery of its tariff autonomy the focal point of its bid to revise the unequal treaties. -

TAI 1 Leiden University Asian Studies (Research), Humanities

TAI 1 Leiden University Asian Studies (Research), Humanities REINTERPRETING THE PAST FOR THE FUTURE: STUDY ON THE HISTORICAL WRITINGS OF PHAN BỘI CHÂU AND HOÀNG CAO KHẢI RAN TAI Supervisor: Dr. Kiri Paramore TAI 2 Abstract This thesis compares the texts of Vietnamese national history written in the colonial period by two competing reformist intellectuals Phan Bội Châu and Hoàng Cao Khải. Exposed to the currents of thought such as Social Darwinism and the theory of evolution in early twentieth century Asia, both of them realised the backwardness of Vietnam and stressed the necessity of reform. However, Phan decided to fight against the French while Hoàng chose to collaborate with them. As will be shown in this thesis, both Phan and Hoàng, despite the difference of their political stances, endeavoured to justify their respective propositions by constructing the historic past of Vietnam. As two reformist intellectuals, Phan Bội Châu and Hoàng Cao Khải regarded the introduction of Western civilisation in late nineteenth century Asia as a key moment for the Vietnamese people to get rid of their backward conditions and evolve into a civilised nation. However, they shared different opinions about the nature of this transition of Vietnam. Phan Bội Châu was inclined to view the French invasion as a “Messianic” moment which marked the “rupture” between the past and present in Vietnamese history. In his historiography, Vietnamese society in the past centuries was inherently barbarous, and this barbarousness led to the current backwardness of the country. Meanwhile, Phan Bội Châu, as an anti-French activist, emphasised that the salvation of the Vietnamese nation should never rely upon the assistance of France. -

Is This Pa Chay Vue? a Study in Three Frames

Is This Pa Chay Vue? A Study in Three Frames JEAN MICHAUD Abstract Three archival photographs recently made public by the French National Library depict men associated with an event taking place in colonial Laos around . However, upon examination of the pictures and textual sources, combined with contemporaneous documents, it turns out that the pictures are actually from Tonkin (colonial northern Vietnam) and may depict Batchai (Pa Chay Vue) a celebrated Hmong messiah in when he met with colonial authorities in an ultimate negotiation attempt before launching a four- year rebellion. Batchai famously led a violent revolt against Tai and French power in Tonkin and Laos between and , which has been documented in French military reports. No photograph has ever been found of the rebel leader and his supporters and this find in itself would be of significance, espec- ially for the Hmong diaspora in the West for whom Pa Chay Vue has achieved near-mythical status as a major folk hero. This article examines whether or not this is him; but beyond the simple task of identifi- cation, it proposes interpretations for the events that suggest a more complex affair than French military archives have ever been willing to tell, including the hypothesis of an administrative cover up. Keywords: critical use of archives; Batchai (Pa Chay Vue); rebellion in colonial Vietnam While the profiles of a significant number of Vietnamese historical figures have been sketched by researchers through mining European colonial archives, the number of profiles generated for similar figures belonging to peripheral non-Kinh ethnicities has remained comparatively low.