The Case of Windhoek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUIDE to CIVIL SOCIETY in NAMIBIA 3Rd Edition

GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA GUIDE TO 3Rd Edition 3Rd Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono and Naita Marowa PJ Rejoice Compiled by GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA 3rd Edition AN OVERVIEW OF THE MANDATE AND ACTIVITIES OF CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS IN NAMIBIA Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA COMPILED BY: Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono PUBLISHED BY: Namibia Institute for Democracy FUNDED BY: Hanns Seidel Foundation Namibia COPYRIGHT: 2018 Namibia Institute for Democracy. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means electronical or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission of the publisher. DESIGN AND LAYOUT: K22 Communications/Afterschool PRINTED BY : John Meinert Printing ISBN: 978-99916-865-5-4 PHYSICAL ADDRESS House of Democracy 70-72 Dr. Frans Indongo Street Windhoek West P.O. Box 11956, Klein Windhoek Windhoek, Namibia EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.nid.org.na You may forward the completed questionnaire at the end of this guide to NID or contact NID for inclusion in possible future editions of this guide Foreword A vibrant civil society is the cornerstone of educated, safe, clean, involved and spiritually each community and of our Democracy. uplifted. Namibia’s constitution gives us, the citizens and inhabitants, the freedom and mandate CSOs spearheaded Namibia’s Independence to get involved in our governing process. process. As watchdogs we hold our elected The 3rd Edition of the Guide to Civil Society representatives accountable. -

Deconstructing Windhoek: the Urban Morphology of a Post-Apartheid City

No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 Working Paper No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Contents PREFACE 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 2. WINDHOEK CONTEXTUALISED ....................................................................... 2 2.1 Colonising the City ......................................................................................... 3 2.2 The Apartheid Legacy in an Independent Windhoek ..................................... 7 2.2.1 "People There Don't Even Know What Poverty Is" .............................. 8 2.2.2 "They Have a Different Culture and Lifestyle" ...................................... 10 3. ON SEGREGATION AND EXCLUSION: A WINDHOEK PROBLEMATIC ........ 11 3.1 Re-Segregating Windhoek ............................................................................. 12 3.2 Race vs. Socio-Economics: Two Sides of the Segragation Coin ................... 13 3.3 Problematising De/Segregation ...................................................................... 16 3.3.1 Segregation and the Excluders ............................................................. 16 3.3.2 Segregation and the Excluded: Beyond Desegregation ....................... 17 4. SUBURBANISING WINDHOEK: TOWARDS GREATER INTEGRATION? ....... 19 4.1 The Municipality's -

Assessing Adherence to Antihypertensive Therapy in Primary Health Care in Namibia: Findings and Implications

Cardiovasc Drugs Ther DOI 10.1007/s10557-017-6756-8 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Assessing Adherence to Antihypertensive Therapy in Primary Health Care in Namibia: Findings and Implications M. M. Nashilongo1 & B. Singu1 & F. Kalemeera1 & M. Mubita1 & E. Naikaku1 & A. Baker2 & A. Ferrario3 & B. Godman2,4,5 & L. Achieng6 & D. Kibuule1 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract variance. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.695. None of the 120 Introduction Namibia has the highest burden and incidence of patients had perfect adherence to antihypertensive therapy, hypertension in sub-Sahara Africa. Though non-adherence to and less than half had acceptable levels of adherence antihypertensive therapy is an important cardiovascular risk (≥ 80%). The mean adherence level was 76.7 ± 8.1%. factor, little is known about potential ways to improve adher- Three quarters of patients ever missed their scheduled ence in Namibia following universal access. The objective of clinic appointment. Having a family support system this study is to validate the Hill-Bone compliance scale and (OR = 5.4, 95% CI 1.687–27.6, p = 0.045) and attendance determine the level and predictors of adherence to antihyper- of follow-up visits (OR = 3.1, 95% CI 1.1–8.7, p =0.03) tensive treatment in primary health care settings in sub-urban were significant predictors of adherence. Having HIV/ townships of Windhoek, Namibia. AIDs did not lower adherence. Methods Reliability was determined by Cronbach’s alpha. Conclusions The modified Namibian version of the Hill- Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to assess con- Bone scale is reliable and valid for assessing adherence to struct validity. -

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE of the REPUBLIC of NAMIBIA No

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA No. 1820 N$2.12 WINDHOEK - 20 March 1998 Advertisements 7. No liability is accepted for any delay in the publication of advertisements/notices, or for the publication of such or any date other than that stipulated by the advertiser. Similarly no liability is accepted in respect of any editing, revision, PROCEDURE FOR ADVERTISING IN THE omission, typographical errors or errors resulting from faint GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC or indistinct copy. OF NAMIBIA 8. The advertiser will be held liable for all compensation and costs arising from any action which may be instituted 1. The Government Gazette (Estates) containing against the Government of Namibia as a result of the advertisements, is published on every Friday. If a Friday falls publication of a notice with or without any omission, errors, on a Public Holiday, this Government Gazette is published on lack of clarity or in any form whatsoever. the preceding Thursday. 9. The subscription for the Government Gazette is 2. Advertisements for publication in thc Government N$474,24 plus GST per annum, obtainable from Central Gazette (Estates) must be addressed to the Government Gazette Bureau Services (Pty) Ltd., Shop 3, Frans Indongo Gardens, Office, P.B. 13302, Windhoek, or be delivered at Cohen P.O. Box 1155, Windhoek. Postage must be prepaid by all Building, Ground Floor, Casino Street entrance, Windhoek, subscribers. Single copies of the Government Gazette are not later than 15:00 on the ninth working day before the date obtainable from Central Bureau Services (Pty) Ltd., Shop 3, of publication of this Government Gazette in which the Frans Indongo Gardens, P.O.Box 1155,Windhoek, at the price advertisement is to be inserted. -

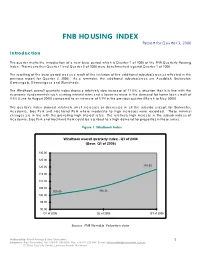

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006 Introduction This quarter marks the introduction of a new base period which is Quarter 1 of 2006 of the FNB Quarterly Housing Index. This means that Quarter 2 and Quarter 3 of 2006 were benchmarked against Quarter 1 of 2006. The resetting of the base period was as a result of the inclusion of five additional suburbs/areas as reflected in the previous report for Quarter 2, 2006. As a reminder, the additional suburbs/areas are Auasblick, Brakwater, Goreangab, Okuryangava and Wanaheda. The Windhoek overall quarterly index shows a relatively slow increase of 11.6%, a situation that is in line with the economic fundamentals such as rising interest rates and a lower increase in the demand for home loan credit of 3.6% (June to August 2006) compared to an increase of 5.9% in the previous quarter (March to May 2006). This quarter’s index showed relatively small increases or decreases in all the suburbs except for Brakwater, Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park where moderate to high increases were recorded. These minimal changes are in line with the prevailing high interest rates. The relatively high increase in the suburb indices of Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park could be ascribed to a high demand for properties in these areas. Figure 1: Windhoek Index Windhoek overall quarterly index - Q3 of 2006 (Base: Q1 of 2006) 130.00 125.00 120.00 118.55 115.00 110.00 105.00 100.00 106.22 100.00 95.00 90.00 Q1 of 2006 Q2 of 2006 Q3 of 2006 Source: FNB Namibia Valuation data Authored by: Martin Mwinga & Alex Shimuafeni 1 Enquiries: Alex Shimuafeni, Tel: +264 61 2992890, Fax: +264 61 225 994, E-mail: [email protected] 5th Floor, First City Centre, Levinson Arcade, Windhoek Brakwater recorded an extraordinary high quarterly increase of 72% from Quarter 2. -

Touring Katutura! : Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism In

Universität Potsdam Malte Steinbrink | Michael Buning | Martin Legant | Berenike Schauwinhold | Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA ! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Potsdamer Geographische Praxis Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Malte Steinbrink|Michael Buning|Martin Legant| Berenike Schauwinhold |Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de/ abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2016 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: -2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Die Schriftenreihe Potsdamer Geographische Praxis wird herausgegeben vom Institut für Geographie der Universität Potsdam. ISSN (print) 2194-1599 ISSN (online) 2194-1602 Das Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Gestaltung: André Kadanik, Berlin Satz: Ute Dolezal Titelfoto: Roman Behrens Druck: docupoint GmbH Magdeburg ISBN 978-3-86956-384-8 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam: URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 11 1.1 Background of the study: -

The State of Food Insecurity in Windhoek, Namibia

THE STATE OF FOOD INSECURITY IN WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA Wade Pendleton, Ndeyapo Nickanor and Akiser Pomuti Pendleton, W., Nickanor, N., & Pomuti, A. (2012). The State of Food Insecurity in Windhoek, Namibia. AFSUN Food Security Series, (14). AFRICAN FOOD SECURITY URBAN NETWORK (AFSUN) AFRICAN FOOD SECURITY URBAN NETWORK (AFSUN) THE STATE OF FOOD INSECURITY IN WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA URBAN FOOD SECURITY SERIES NO. 14 AFRICAN FOOD SECURITY URBAN NETWORK (AFSUN) THE STATE OF FOOD INSECURITY IN WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA WADE PENDLETON, NDEYAPO NICKANOR AND AKISER POMUTI SERIES EDITOR: PROF. JONATHAN CRUSH URBAN FOOD SECURITY SERIES NO. 14 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The financial support of the Canadian International Development Agency for AFSUN and this publication is acknowledged. Cover Photograph: Aaron Price, http://namibiaafricawwf.blogspot.com Published by African Food Security Urban Network (AFSUN) © AFSUN 2012 ISBN 978-1-920597-01-6 First published 2012 Production by Bronwen Müller, Cape Town All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans- mitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the publisher. Authors Wade Pendleton is a Research Associate of the African Food Security Urban Network. Ndeyapo Nickanor is a Lecturer at the University of Namibia. Akiser Pomuti is Director of the University Central Consultancy Bureau at the University of Namibia. Previous Publications in the AFSUN Series No 1 The Invisible Crisis: Urban Food Security in Southern Africa No 2 The State of Urban Food Insecurity in Southern Africa No -

Final Project Report for 2016 START Grants for Global Change Research in Africa

Final Project Report for 2016 START Grants for Global Change Research in Africa Project Title Water Security in Windhoek: governance, water demand and supply, and livelihoods in the context of urbanization and climate change Abstract Governance In the study, UJAMS Waste Water Treatment Plant (UWWTP) served as a case study to investigate governance and policy analysis in relation to water security in the city of Windhoek. The study revealed that there are different actors that were involved in discussion and decision making to address the issue of water supply to industries, pollution from industrial effluent and the need to find diverse alternatives to the water insecurity problem that ultimately led to establishment and operation of the (UWWTP) Analysis of Water Management Plan for City of Windhoek 2017 and Transformational Strategic Plan (2017-2022) for City of Windhoek policies revealed that despite being developed recently after the Namibia Climate Change Policy, Strategy and Action Plan had been enacted, very little climate change related issues are mainstreamed and used in these policies despite Windhoek. Water demand and supply In central Namibia, where the Capital Windhoek is hosted, water is very scarce. To cope with the effect of drought, water is transferred from Kombat Karst Aquifer and Von Bach and Swakoppoort dam on the Swakop River. The effect of drought on the Swakop River is not well known. To understand the effect of drought, streamflow, and rainfall data from 1969 to 2016 were collected and analyzed using drought indices such as Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) and Streamflow Drought Index (SDI). It was found that, drought periods were not continuous and a wet period was always followed. -

Critical Geopolitics of Foreign Involvement in Namibia: a Mixed Methods Approach

CRITICAL GEOPOLITICS OF FOREIGN INVOLVEMENT IN NAMIBIA: A MIXED METHODS APPROACH by MEREDITH JOY DEBOOM B.A., University of Iowa, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Geography 2013 This thesis entitled: Critical Geopolitics of Foreign Involvement in Namibia: A Mixed Methods Approach written by Meredith Joy DeBoom has been approved for the Department of Geography John O’Loughlin, Chair Joe Bryan, Committee Member Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Abstract DeBoom, Meredith Joy (M.A., Geography) Critical Geopolitics of Foreign Involvement in Namibia: A Mixed Methods Approach Thesis directed by Professor John O’Loughlin In May 2011, Namibia’s Minister of Mines and Energy issued a controversial new policy requiring that all future extraction licenses for “strategic” minerals be issued only to state-owned companies. The public debate over this policy reflects rising concerns in southern Africa over who should benefit from globally-significant resources. The goal of this thesis is to apply a critical geopolitics approach to create space for the consideration of Namibian perspectives on this topic, rather than relying on Western geopolitical and political discourses. Using a mixed methods approach, I analyze Namibians’ opinions on foreign involvement, particularly involvement in natural resource extraction, from three sources: China, South Africa, and the United States. -

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location Henning Melber1 Abstract The Windhoek Old Location refers to what had been the South West African capital’s Main Lo- cation for the majority of black and so-called Colored people from the early 20th century until 1960. Their forced removal to the newly established township Katutura, initiated during the late 1950s, provoked resistance, popular demonstrations and escalated into violent clashes between the residents and the police. These resulted in the killing and wounding of many people on 10 December 1959. The Old Location since became a synonym for African unity in the face of the divisions imposed by apartheid. Based on hitherto unpublished archival documents, this article contributes to a not yet exist- ing social history of the Old Location during the 1950s. It reconstructs aspects of the daily life among the residents in at that time the biggest urban settlement among the colonized majority in South West Africa. It revisits and portraits a community, which among former residents evokes positive memories compared with the imposed new life in Katutura and thereby also contributed to a post-colonial heroic narrative, which integrates the resistance in the Old Location into the patriotic history of the anti-colonial liberation movement in government since Independence. O Lord, help us who roam about. Help us who have been placed in Africa and have no dwelling place of our own. Give us back a dwelling place.2 The Old Location was the Main Location for most of the so-called non-white residents of Wind- hoek from the early 20th century until 1960, while a much smaller location also existed until 1961 in Klein Windhoek. -

Public Notice Electoral Commission of Namibia

The Electoral Commission of Namibia herewith publishes the names of the Political Party lists of Candidates for the National Assembly elections which will be gazzetted on 7th November 2019. If any person’s name appears on a list without their consent, they can approach the Commission in writing in terms of Section 78 (2) of the Electoral Act, No. 5 of 2014. In such cases the Electoral Act of 2014 empowers the Commission to make withdrawals or removals of candidates after gazetting by publishing an amended notice. NATIONAL ASSEMBY ELECTIONS POLITICAL PARTIES CANDIDATE LIST 2019 PUBLIC NOTICE ELECTORAL COMMISSION OF NAMIBIA NOTIFICATION OF REGISTERED POLITICAL PARTIES AND LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR REGISTERED POLITICAL PARTIES: GENERAL ELECTION FOR ELECTION OF MEMBERS OF NATIONAL ASSEMBLY: ELECTORAL ACT, 2014 In terms of section 78(1) of the Electoral Act, 2014 (Act no. 5 of 2014), the public is herewith notified that for the purpose of the general election for the election of members of the National Assembly on 27 November 2019 – (a) The names of all registered political parties partaking in the general election for the election of the members of the National Assembly are set out in Schedule 1; (b) The list of candidates of each political party referred to in paragraph (a), as drawn up by the political parties and submitted in terms of section 77 of that Act for the election concerned is set out in Schedule 2; and (c) The persons whose names appear on that list referred to in paragraph (b) have been duly nominated as candidates of the political party concerned for the election. -

The Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Nurses Regarding the Provision of Services on Cervical Cancer at Healthcare Facilities in Windhoek District, Namibia

THE KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDE AND PRACTICES OF NURSES REGARDING THE PROVISION OF SERVICES ON CERVICAL CANCER AT HEALTHCARE FACILITIES IN WINDHOEK DISTRICT, NAMIBIA NDAHAFA A SHIWEDA NOVEMBER 2019 i THE KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDE AND PRACTICES OF NURSES REGARDING THE PROVISION OF SERVICES ON CERVICAL CANCER AT HEALTHCARE FACILITIES IN WINDHOEK DISTRICT, NAMIBIA A RESEARCH THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE MASTERS DEGREE OF NURSING SCIENCE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAMIBIA BY NDAHAFA A SHIWEDA 201304589 NOVEMBER 2019 MAIN SUPERVISOR: DR HANS J AMUKUGO ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to determine the knowledge, attitudes and practices of nurses regarding the provision of services on cervical cancer at the health facilities in Windhoek district, Namibia. To achieve this aim, four objectives were set: (a) to assess the knowledge of cervical cancer and cervical cancer services among nurses (b) to determine the nurses' attitudes towards the provision of cervical cancer services (c) to assess the practices of nurses towards the provision of services on cervical cancer; and (d) to analyse the association between the key variables with regards to cervical cancer and the provision of its services. A quantitative, descriptive and analytical study, using a self-administered structured questionnaire was completed in 2019. Data on socio-demographic, knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding cervical cancer service provision was collected from nurses that are working at the randomly selected healthcare facilities such as Windhoek Central hospitals, Intermediate Katutura Hospital, Hakahana clinic, Wanaheda clinic, Okuryangava clinic and Katutura Health Centre. A total of eighty (80) participants was sampled with the means of stratified random sampling, proportionate to the size of the population at a certain health facility.