Working with Seaweed in North-West Sutherland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

805 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

805 bus time schedule & line map 805 Inshes View In Website Mode The 805 bus line (Inshes) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Inshes: 8:00 AM (2) Leirinmore: 2:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 805 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 805 bus arriving. Direction: Inshes 805 bus Time Schedule 80 stops Inshes Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 8:00 AM Smoo Cave, Leirinmore Tuesday 8:00 AM Hall, Leirinmore Wednesday Not Operational Church, Durness Thursday 8:00 AM Churchend Road, Scotland Friday Not Operational Visitor Centre, Durness Saturday 8:00 AM Post O∆ce, Durness Balnakeil Craft Village, Durness Road End, Keoldale 805 bus Info Direction: Inshes Kinlochbervie Road End, Rhiconich Stops: 80 Trip Duration: 230 min East Road End, Achriesgill Line Summary: Smoo Cave, Leirinmore, Hall, Leirinmore, Church, Durness, Visitor Centre, Durness, Post O∆ce, Durness, Balnakeil Craft Village, Durness, West Road End, Achriesgill Road End, Keoldale, Kinlochbervie Road End, Rhiconich, East Road End, Achriesgill, West Road Rhuvolt Road End, Inshegra End, Achriesgill, Rhuvolt Road End, Inshegra, Post Box, Badcall, Manse Road, Kinlochbervie, Burnside, Post Box, Badcall Kinlochbervie, Ceilidh House, Kinlochbervie, Bervie Road, Kinlochbervie, Harbour, Kinlochbervie, Bervie Manse Road, Kinlochbervie Road, Kinlochbervie, Ceilidh House, Kinlochbervie, Burnside, Kinlochbervie, Manse Road, Kinlochbervie, Burnside, Kinlochbervie Post Box, Badcall, Rhuvolt Road End, Inshegra, West -

Walks and Scrambles in the Highlands

Frontispiece} [Photo by Miss Omtes, SLIGACHAN BRIDGE, SGURR NAN GILLEAN AND THE BHASTEIR GROUP. WALKS AND SCRAMBLES IN THE HIGHLANDS. BY ARTHUR L. BAGLEY. WITH TWELVE ILLUSTRATIONS. Xon&on SKEFFINGTON & SON 34 SOUTHAMPTON STREET, STRAND, W.C. PUBLISHERS TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING I9H Richard Clav & Sons, Limiteu, brunswick street, stamford street s.e., and bungay, suffolk UNiVERi. CONTENTS BEN CRUACHAN ..... II CAIRNGORM AND BEN MUICH DHUI 9 III BRAERIACH AND CAIRN TOUL 18 IV THE LARIG GHRU 26 V A HIGHLAND SUNSET .... 33 VI SLIOCH 39 VII BEN EAY 47 VIII LIATHACH ; AN ABORTIVE ATTEMPT 56 IX GLEN TULACHA 64 X SGURR NAN GILLEAN, BY THE PINNACLES 7i XI BRUACH NA FRITHE .... 79 XII THROUGH GLEN AFFRIC 83 XIII FROM GLEN SHIEL TO BROADFORD, BY KYLE RHEA 92 XIV BEINN NA CAILLEACH . 99 XV FROM BROADFORD TO SOAY . 106 v vi CONTENTS CHAF. PACE XVI GARSBHEINN AND SGURR NAN EAG, FROM SOAY II4 XVII THE BHASTEIR . .122 XVIII CLACH GLAS AND BLAVEN . 1 29 XIX FROM ELGOL TO GLEN BRITTLE OVER THE DUBHS 138 XX SGURR SGUMA1N, SGURR ALASDAIR, SGURR TEARLACH AND SGURR MHIC CHOINNICH . I47 XXI FROM THURSO TO DURNESS . -153 XXII FROM DURNESS TO INCHNADAMPH . 1 66 XXIII BEN MORE OF ASSYNT 1 74 XXIV SUILVEN 180 XXV SGURR DEARG AND SGURR NA BANACHDICH . 1 88 XXVI THE CIOCH 1 96 1 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Toface page SLIGACHAN BRIDGE, SGURR NAN GILLEAN AND THE bhasteir group . Frontispiece BEN CRUACHAN, FROM NEAR DALMALLY . 4 LOCH AN EILEAN ....... 9 AMONG THE CAIRNGORMS ; THE LARIG GHRU IN THE DISTANCE . -31 VIEW OF SKYE, FROM NEAR KYLE OF LOCH ALSH . -

CAISTEAL BHARRAICH, DUN VARRICH and the WIDER TRADITION 8Ugb Cheape

CAISTEAL BHARRAICH, DUN VARRICH AND THE WIDER TRADITION 8ugb Cheape Caisteal Bharraich, anglicised in the past as ·Castle Varrich', is one of the few structures of its type in the north of Scotland, and its site is a conspicuous one. The ruinous building stands on a promontory on the east side and near the head of the Kyle of Tongue (OS Grid Reference NC 581 568). The structure has been a square tower \vith walls ofrandom rubble masonry bedded with a coarse lime mortar, about 1.35m thick on average and standing at least two storeys in height. The ground floor or ·laigh hoose' .. with a door to the outside and narrow window .. is vaulted and has a floor area approximately 4m square. The upper floor, to which there is no stair .. has probably had a fireplace although the detail is not clear. There are sets offour slots on each ofthe north and south walls respectively, presumably for joists or couples on which the upper storeys were carried. Given the dimension, construction and the weight of masonry, the structure may well have had a third storey and even a °loft'. Descriptions of the building tend to limit themselves to these few facts and to topographical impressions ofthe surrounding ground surface (RCAHMS 1911, 183). In any attempt to take the interpretation further we tend to define and categorise in conventional Scottish terms .. claiming for example that the building appears to have been a towerhouse strongly characteristic of Scottish medieval architecture, and it is included in these terms in the standard sources (MacGibbon and Ross 1889, iii, 253-6). -

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide 2 Introduction Scotland is surrounded by coastal water – the North Sea, the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. In addition, there are also numerous bodies of inland water including rivers, burns and about 25,000 lochs. Being safe around water should therefore be a key priority. However, the management of water safety is a major concern for Scotland. Recent research has found a mixed picture of water safety in Scotland with little uniformity or consistency across the country.1 In response to this research, it was suggested that a framework for a water safety policy be made available to local authorities. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) has therefore created this document to assist in the management of water safety. In order to support this document, RoSPA consulted with a number of UK local authorities and organisations to discuss policy and water safety management. Each council was asked questions around their own area’s priorities, objectives and policies. Any policy specific to water safety was then examined and analysed in order to help create a framework based on current practice. It is anticipated that this framework can be localised to each local authority in Scotland which will help provide a strategic and consistent national approach which takes account of geographical areas and issues. Water Safety Policy in Scotland— A Guide 3 Section A: The Problem Table 1: Overall Fatalities 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 Data from National Water Safety Forum, WAID database, July 14 In recent years the number of drownings in Scotland has remained generally constant. -

Sutherland Futures-P22-24

THINGS YOU NEED TO NOTE ALTNAHARRA, OUTLYING TOWNSHIPS INCHNADAMPH, FORSINARD Reinforcing rural townships where development is consistent with the pattern of AND KINBRACE settlement, service capacity and local amenity is encouraged. Central South and East North West Achnahannat Achuan Achlyness Several traditional staging posts within the remote and sparsely populated Achnairn Achavandra Muir Achmelvich interior continue to offer lifeline services in remote, fragile communities. Altass Achrimsdale-East Achnacarin Prospects are dependent on sustained employment in estate/land management, Amat Clyne Achriesgill (east and tourism and interpretive facilities and local enterprise. Development pressures Astle Achue west) are negligible. Given a lack of first-time infrastructure, a flexible development Linside Ardachu Badcall regime needs to balance safeguards for the existing character and environmental Linsidemore Backies Badnaban standards. Migdale Badnellan Balchladich Spinningdale Badninish Blairmore Camore Clachtoll Clashbuidh Clashmore What key sites are most suitable? What key sites North are least suitable? Does the Settlement Clashmore Clashnessie Achininver Crakaig Crofts- Culkein Development Area suitably reflect the limits of Baligill Lothmore Culkein of Drumbeg ?? your community for future development? Blandy/Strathtongue ??? Crofthaugh Droman Braetongue/ Brae Culgower-West Garty Elphin What development or facilities does your Kirkiboll Lodge Foindle Clerkhill community need and where? Culrain Inshegra Coldbackie Dalchalm Inverkirkaig -

Scottish Highlands Hillwalking

SHHG-3 back cover-Q8__- 15/12/16 9:08 AM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Scottish Highlands Hillwalking 60 DAY-WALKS – INCLUDES 90 DETAILED TRAIL MAPS – INCLUDES 90 DETAILED 60 DAY-WALKS 3 ScottishScottish HighlandsHighlands EDN ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. They are particularly strong on mapping...’ HillwalkingHillwalking THE SUNDAY TIMES Scotland’s Highlands and Islands contain some of the GUIDEGUIDE finest mountain scenery in Europe and by far the best way to experience it is on foot 60 day-walks – includes 90 detailed trail maps o John PLANNING – PLACES TO STAY – PLACES TO EAT 60 day-walks – for all abilities. Graded Stornoway Durness O’Groats for difficulty, terrain and strenuousness. Selected from every corner of the region Kinlochewe JIMJIM MANTHORPEMANTHORPE and ranging from well-known peaks such Portree Inverness Grimsay as Ben Nevis and Cairn Gorm to lesser- Aberdeen Fort known hills such as Suilven and Clisham. William Braemar PitlochryPitlochry o 2-day and 3-day treks – some of the Glencoe Bridge Dundee walks have been linked to form multi-day 0 40km of Orchy 0 25 miles treks such as the Great Traverse. GlasgowGla sgow EDINBURGH o 90 walking maps with unique map- Ayr ping features – walking times, directions, tricky junctions, places to stay, places to 60 day-walks eat, points of interest. These are not gen- for all abilities. eral-purpose maps but fully edited maps Graded for difficulty, drawn by walkers for walkers. terrain and o Detailed public transport information strenuousness o 62 gateway towns and villages 90 walking maps Much more than just a walking guide, this book includes guides to 62 gateway towns 62 guides and villages: what to see, where to eat, to gateway towns where to stay; pubs, hotels, B&Bs, camp- sites, bunkhouses, bothies, hostels. -

Beachview, 165 Drumnaguie, Rhiconich, Lairg

Beachview, 165 Drumnaguie, Rhiconich, Lairg Beachview, further double bedrooms, all three benefitting from built-in wardrobes, together with a modern 165 Drumnaguie, family bathroom with corner bath. Rhiconich, Lairg IV27 4RT Outside The property is approached over a gravelled A modern detached home in beautiful driveway providing parking for multiple vehicles. surroundings with stunning far reaching The stock-fenced garden is a continuation of coastal views, within close proximity of the surrounding croftland interspersed with the beach. numerous large rocks, each many millions of years old, and features numerous seating areas and a spacious raised wraparound viewing deck, all ideal for entertaining and al fresco dining and Kinlochbervie 3 miles, Lairg 50 miles, Inverness for enjoying the incredible views across Polin 97 miles Beach to Handa Island beyond. Entrance porch | Hall | Sitting room | Dining room | Kitchen/breakfast room | Utility room Shower room | 4 Bedrooms | Family bathroom Location EPC Rating D The property is located on the north-west coast of Sutherland in the hamlet of Drumnaguie within a very short distance of Polin Beach, a scenic cove with white sand and clear blue The property waters. The fishing and harbour village of Beachview offers attractive light-filled Kinlochbervie, the most northerly port on the accommodation arranged over two floors, and west coast of Scotland, offers a good range as its name implies is designed to maximise of day-to-day amenities including a general the truly stunning views over Polin Beach. store, Post Office, hardware store, café, health The welcoming reception hall leads to a centre, hotel, garage, nursery, primary and spacious sitting room with wooden flooring, secondary schooling, together with a travelling corner fireplace with inset woodburning stove bank and some supermarkets also delivering and patio doors to the garden deck, a well- to the area. -

Volume 150 Celebration Paper

Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 150, 1993, pp. 447-464, 10 figs. Printed in Northern Ireland Volume 150 Celebration Paper Unravelling dates through the ages: geochronology of the Scottish metamorphic complexes G. ROGERS 1 & R.J. PANKHURST 2 l lsotope Geology Unit, Scottish Universities Research and Reactor Centre, East Kilbride, Glasgow G75 OQU, UK 2British Antarctic Survey, c/o NERC Isotope Geosciences Laboratory, Kingsley Dunham Centre, Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG, UK Abstract: The paper by Giletti et al. (1961) is seen as a major landmark in the evolution of dating techniques in polymetamorphic terrains. We consider certain critical issues from each of the main complexes of the Scottish Highlands studied by Giletti et al. to illustrate how subsequent develop- ments in geochronological methodology have influenced our understanding of metamorphic belts. Lewisian examples focus on the formation of Archaean crust, and the age of the main high-grade metamorphism and the Scourie dyke swarm. The antiquity of Moinian sedimentation, its relationship to the Torridonian sandstones, and the timing of Precambrian metamorphism have been controversial issues. The timing and nature of Caledonian orogenesis, most clearly expressed in the Dalradian complex, have been the focal points for the refinement of radiometric investigation. These complexes have been subject to successive developments in methodology, with ever-tighter constraints from Rb-Sr and K-Ar mineral dating, through Rb-Sr and Pb-Pb whole-rock studies, U-Pb dating of bulk zircon fractions, and Sm-Nd whole-rock and mineral investigation, up to the latest technologies of single-grain zircon and ion microprobe analysis. -

Mapping Farmland Wader Distributions and Population Change to Identify Wader Priority Areas for Conservation and Management Action

Mapping farmland wader distributions and population change to identify wader priority areas for conservation and management action Scott Newey1*, Debbie Fielding1, and Mark Wilson2 1. The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen, AB15 8QH 2. The British Trust for Ornithology Scotland, Stirling, FK9 4NF * [email protected] Introduction Many birds have declined across Scotland and the UK as a whole (Balmer et al. 2013, Eaton et al. 2015, Foster et al. 2013, Harris et al. 2017). These include five species of farmland wader; oystercatcher, lapwing, curlew, redshank and snipe. All of these have all been listed as either red or amber species on the UK list of birds of conservation concern (Harris et al. 2017, Eaton et al. 2015). Between 1995 and 2016 both lapwing and curlew declined by more than 40% in the UK (Harris et al. 2017). The UK harbours an estimated 19-27% of the curlew’s global breeding population, and the curlew is arguably the most pressing bird conservation challenge in the UK (Brown et al. 2015). However, the causes of wader declines likely include habitat loss, alteration and homogenisation (associated strongly with agricultural intensification), and predation by generalist predators (Brown et al. 2015, van der Wal & Palmer 2008, Ainsworth et al. 2016). There has been a concerted effort to reverse wader declines through habitat management, wader sensitive farming practices and predator control, all of which are likely to benefit waders at the local scale. However, the extent and severity of wader population declines means that large scale, landscape level, collaborative actions are needed if these trends are to be halted or reversed across much of these species’ current (and former) ranges. -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

NORTHWEST © Lonelyplanetpublications Northwest Northwest 256 and Thedistinctive, Seeminglyinaccessiblepeakstacpollaidh

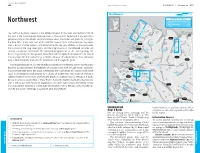

© Lonely Planet Publications 256 www.lonelyplanet.com NORTHWEST •• Information 257 0 10 km Northwest 0 6 miles Northwest – Maps Cape Wrath 1 Sandwood Bay & Cape Wrath p260 Northwest Faraid 2 Ben Loyal p263 Head 3 Eas a' Chùal Aluinn p266 H 4 Quinag p263 Durness C Sandwood Creag Bay S Riabach Keoldale t (485m) To Thurso The north of Scotland, beyond a line joining Ullapool in the west and Dornoch Firth in r Kyle of N a (20mi) t Durness h S the east, is the most sparsely populated part of the country. Sutherland is graced with a h i n Bettyhill I a r y 1 Blairmore A838 Hope of Tongue generous share of the wildest and most remote coast, mountains and glens. At first sight, Loch Eriboll M Kinlochbervie Tongue the bare ‘hills’, more rock than earth, and the maze of lochs and waterways may seem Loch Kyle B801 Cranstackie Hope alien – part of another planet – and unattractive. But the very wildness of the rockscapes, (801m) r Rudha Rhiconich e Ruadh An Caisteal v the isolation of the long, deep glens, and the magnificence of the indented coastline can E (765m) a A838 Foinaven n Laxford (911m) Ben Hope h Loch t exercise a seductive fascination. The outstanding significance of the area’s geology has Bridge (927m) H 2 Loyal a r been recognised by the designation of the North West Highlands Geopark (see the boxed t T Scourie S Loch Ben Stack Stack A836 text on p264 ), the first such reserve in Britain. Intrusive developments are few, and many (721m) long-established paths lead into the mountains and through the glens. -

M A'h.^ I'i.Mi V

M A'H.^ i'i.Mi ■ v-’Vw''. 71 I ■ •M )-W: ScS. ZbS. /I+S SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY . FOURTH SERIES VOLUME 9 Papers on Sutherland Estate Management Volume 2 . PAPERS ON SUTHERLAND ESTATE MANAGEMENT 1802-1816 edited by R. J. Adam, m.a. Volume 2 ★ ★ EDINBURGH printed for the Scottish History Society by T. AND A. CONSTABLE LTD 1972 © Scottish History Society 1972 . SBN 9500260 3 4 (set of two volumes) SBN 9500260 5 o (this volume) Printed in Great Britain A generous contribution from the Leverhulme Trust towards the cost of producing this volume is gratefully acknowledged by the Council of the Society CONTENTS SUTHERLAND ESTATE MANAGEMENT CORRESPONDENCE 1802-1807: The factory of David Campbell 1 1807-1811: The factory of Cosmo Falconer 63 1811-1816: The factory of William Young 138 Index 305 1802-1807 LETTERS RELATING TO THE FACTORY OF DAVID CAMPBELL Colin Mackenzie to Countess of Sutherland Tongue, 14 September 1799 as 1 conclude that Your Ladyship will be desirous to know the result of my journey to Assint which I have now left, I take the opportunity of the first Place from which the Post goes to the South to address these lines to you for your and Lord Gower’s information. The people had been summoned to meet us at the Manse and most of the old men attended; few of the Sons. There was plainly a Combination fostered by the hope that if they adhered together any threats would be frustrated. All we got in two days was 4 Recruits. In these two days however we proceeded regularly to Call on the people of each farm progressively and thus showed them that none of the refractory would be overlooked.