CAISTEAL BHARRAICH, DUN VARRICH and the WIDER TRADITION 8Ugb Cheape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walks and Scrambles in the Highlands

Frontispiece} [Photo by Miss Omtes, SLIGACHAN BRIDGE, SGURR NAN GILLEAN AND THE BHASTEIR GROUP. WALKS AND SCRAMBLES IN THE HIGHLANDS. BY ARTHUR L. BAGLEY. WITH TWELVE ILLUSTRATIONS. Xon&on SKEFFINGTON & SON 34 SOUTHAMPTON STREET, STRAND, W.C. PUBLISHERS TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING I9H Richard Clav & Sons, Limiteu, brunswick street, stamford street s.e., and bungay, suffolk UNiVERi. CONTENTS BEN CRUACHAN ..... II CAIRNGORM AND BEN MUICH DHUI 9 III BRAERIACH AND CAIRN TOUL 18 IV THE LARIG GHRU 26 V A HIGHLAND SUNSET .... 33 VI SLIOCH 39 VII BEN EAY 47 VIII LIATHACH ; AN ABORTIVE ATTEMPT 56 IX GLEN TULACHA 64 X SGURR NAN GILLEAN, BY THE PINNACLES 7i XI BRUACH NA FRITHE .... 79 XII THROUGH GLEN AFFRIC 83 XIII FROM GLEN SHIEL TO BROADFORD, BY KYLE RHEA 92 XIV BEINN NA CAILLEACH . 99 XV FROM BROADFORD TO SOAY . 106 v vi CONTENTS CHAF. PACE XVI GARSBHEINN AND SGURR NAN EAG, FROM SOAY II4 XVII THE BHASTEIR . .122 XVIII CLACH GLAS AND BLAVEN . 1 29 XIX FROM ELGOL TO GLEN BRITTLE OVER THE DUBHS 138 XX SGURR SGUMA1N, SGURR ALASDAIR, SGURR TEARLACH AND SGURR MHIC CHOINNICH . I47 XXI FROM THURSO TO DURNESS . -153 XXII FROM DURNESS TO INCHNADAMPH . 1 66 XXIII BEN MORE OF ASSYNT 1 74 XXIV SUILVEN 180 XXV SGURR DEARG AND SGURR NA BANACHDICH . 1 88 XXVI THE CIOCH 1 96 1 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Toface page SLIGACHAN BRIDGE, SGURR NAN GILLEAN AND THE bhasteir group . Frontispiece BEN CRUACHAN, FROM NEAR DALMALLY . 4 LOCH AN EILEAN ....... 9 AMONG THE CAIRNGORMS ; THE LARIG GHRU IN THE DISTANCE . -31 VIEW OF SKYE, FROM NEAR KYLE OF LOCH ALSH . -

Scottish Highlands Hillwalking

SHHG-3 back cover-Q8__- 15/12/16 9:08 AM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Scottish Highlands Hillwalking 60 DAY-WALKS – INCLUDES 90 DETAILED TRAIL MAPS – INCLUDES 90 DETAILED 60 DAY-WALKS 3 ScottishScottish HighlandsHighlands EDN ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. They are particularly strong on mapping...’ HillwalkingHillwalking THE SUNDAY TIMES Scotland’s Highlands and Islands contain some of the GUIDEGUIDE finest mountain scenery in Europe and by far the best way to experience it is on foot 60 day-walks – includes 90 detailed trail maps o John PLANNING – PLACES TO STAY – PLACES TO EAT 60 day-walks – for all abilities. Graded Stornoway Durness O’Groats for difficulty, terrain and strenuousness. Selected from every corner of the region Kinlochewe JIMJIM MANTHORPEMANTHORPE and ranging from well-known peaks such Portree Inverness Grimsay as Ben Nevis and Cairn Gorm to lesser- Aberdeen Fort known hills such as Suilven and Clisham. William Braemar PitlochryPitlochry o 2-day and 3-day treks – some of the Glencoe Bridge Dundee walks have been linked to form multi-day 0 40km of Orchy 0 25 miles treks such as the Great Traverse. GlasgowGla sgow EDINBURGH o 90 walking maps with unique map- Ayr ping features – walking times, directions, tricky junctions, places to stay, places to 60 day-walks eat, points of interest. These are not gen- for all abilities. eral-purpose maps but fully edited maps Graded for difficulty, drawn by walkers for walkers. terrain and o Detailed public transport information strenuousness o 62 gateway towns and villages 90 walking maps Much more than just a walking guide, this book includes guides to 62 gateway towns 62 guides and villages: what to see, where to eat, to gateway towns where to stay; pubs, hotels, B&Bs, camp- sites, bunkhouses, bothies, hostels. -

Mapping Farmland Wader Distributions and Population Change to Identify Wader Priority Areas for Conservation and Management Action

Mapping farmland wader distributions and population change to identify wader priority areas for conservation and management action Scott Newey1*, Debbie Fielding1, and Mark Wilson2 1. The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen, AB15 8QH 2. The British Trust for Ornithology Scotland, Stirling, FK9 4NF * [email protected] Introduction Many birds have declined across Scotland and the UK as a whole (Balmer et al. 2013, Eaton et al. 2015, Foster et al. 2013, Harris et al. 2017). These include five species of farmland wader; oystercatcher, lapwing, curlew, redshank and snipe. All of these have all been listed as either red or amber species on the UK list of birds of conservation concern (Harris et al. 2017, Eaton et al. 2015). Between 1995 and 2016 both lapwing and curlew declined by more than 40% in the UK (Harris et al. 2017). The UK harbours an estimated 19-27% of the curlew’s global breeding population, and the curlew is arguably the most pressing bird conservation challenge in the UK (Brown et al. 2015). However, the causes of wader declines likely include habitat loss, alteration and homogenisation (associated strongly with agricultural intensification), and predation by generalist predators (Brown et al. 2015, van der Wal & Palmer 2008, Ainsworth et al. 2016). There has been a concerted effort to reverse wader declines through habitat management, wader sensitive farming practices and predator control, all of which are likely to benefit waders at the local scale. However, the extent and severity of wader population declines means that large scale, landscape level, collaborative actions are needed if these trends are to be halted or reversed across much of these species’ current (and former) ranges. -

Welcome to the Tongue Hotel a Hearty Taste of the Highlands…

Welcome to the Tongue Hotel A hearty taste of the Highlands….. Recommended Aperitifs Recommended Scottish Gin of the week: Rock Rose from Dunnet Bay Distillery, a new gin for every season! Served with interesting garnishes, ice and Fever Tree Tonic Starters Soup of the day: choose from £5.50 Leek and sweet potato (V/DF) (GF avail) Lentil, apricot and cumin (V/DF) (GF avail) Kyle of Tongue oysters (5) (GF/DF) £9.50 Red onion vinaigrette, side salad Ullapool landed langoustines (GF/DF avail) Starter £10.50 Garlic butter and leaves (chips with mains course) Main £24.50 Tempura and sesame chicken strips (DF/GF) £6.50 Lime and basil aioli, crispy kale Duck and orange parfait (GF avail) £7.50 Homemade tomato chutney, oatcakes Sweet potato and avocado tartare (Ve/V/DF) (GF avail - no gazpacho) £7.50 Gazpacho, burnt orange segments Main Courses Pan roasted fillet of north coast salmon (GF/DF avail) £19.50 Chargrilled Mediterranean vegetables, dauphinois potato, lemon and caper butter Duo of Highland pork (GF) £19.50 Slow roasted pork belly and tenderloin, parsnip and apple purée, gratin dauphinois, Wilted greens, pan jus Black Isle lamb shank (GF) £18.50 Creamy mashed potato, pak choi, honey glazed carrots, lamb jus Pan fried Scottish chicken supreme (GF) £18.50 Fondant potato, mushroom duxelles, mixed greens, red wine jus Please make allergies known! Note our salad dressing contains mustard seeds Locally Sourced - Produced with Pride 10oz Black Isle sirloin steak (GF) (DF avail) £24.50 Sauté potatoes, roasted tomatoes, onions and mushrooms, -

Summer Sailings

;{': H ® SUMMEE SAILINGS BY AN OLD YACHTSMAN AECHIBALD YOUNG, Advocate LATE H.M. INSPECTOR OF SALMON FISHERIES FOR SCOTLAND AND AUTHOR OF 'TREATISE ON SALMON' IN 'STANFORD'S HISTORY OF BRITISH INDUSTRIES,' PRIZE ESSAY ON HARBOUR ACCOMMODATION FOR FISHING BOATS, 'THE ANGLER AND SKETCHER'S GUIDE TO SUTHERLAND,' ETC. ETC. WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS AFTER WATER- COLOUR DRAWINGS BY THE AUTHOR EDINBUEGH: DAVID DOUGLAS 1898 4 <r PEEFACE The following cruises occupied several summer seasons a good many years ago. They were made in a cutter yacht of thirty-five tons, in which I sailed more than 7000 miles, going twice round Great Britain, visiting the Orkney and Shetland Islands, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, and also parts of Ireland, France, and Norway. An account of one or two of the cruises appeared in well-known magazines. But the whole of them are now pub- lished for the first time in a complete form ; and it is hoped that the numerous illustrations of picturesque localities, all taken from water-colour drawings made by me on the spot in the course of these cruises, will add something to the interest and value of the volume. The black and white illustrations were made from my drawings by Messrs. J. Munro Bell and Co. , Edinburgh ; and vi SUMMER SAILINGS for • the coloured illustrations I am indebted to Messrs. R. S. and W. Forrest, Brandon Street Studio, Edinburgh, who first photographed the drawings, and then coloured them by hand after the original sketches. ARCHIBALD YOUNG. 22 Royal Circus, Edinburgh, January 1898. CASTLE VAKRICH AND BEN LAOGHAL — CONTENTS CHAPTER I North About—Cruise from Forth to Clyde Pleasures and advantages of a yacht cruise in summer to the remote Highlands and Islands of Scotland — Description of the yacht Spray—Town and Bay of Stromness—Loch of Stenness — Druidi- cal circle of Stenness—Ward Hill of Hoy—Three tall Standing Stones of Stenness—Kirkwall the capital of the Orkney Islands—Cathedral of St. -

Island Place-Names

Island Place-names Dr Jacob King The names of Scotland’s islands are a fascinating window into the country’s linguistic landscape; the languages of the Gaels, the Vikings and the Angles have all left their mark across the north-western seaboard. The Earliest names Evidence from historical sources suggest there may have existed an unknown language in Scotland prior to the arrival of the later, historic languages. This language might have been utterly forgotten were it not for a handful of names of rivers, islands and regions. Many theories have been put forward as to the identity of the language from which these names derive and what the names may have originally meant, but the jury is still out on the majority of them. Names such as Mull, Unst and Uist all defy analysis. Likewise, Islay is from Gaelic Ìle, the -s- in the English form was inserted on analogy with words like isle and island, but its original meaning has nonetheless been lost. Lewis appears to be from a Norse word Ljóðhús meaning ‘song house’; this is rather an odd name to be given to an island, maybe the Norse adapted it from an earlier unknown language? Norse Names At least in the north, the first historical people to make their linguistic mark on the Scottish seaboard were the Norse or the Vikings. Being a seafaring people, it is no surprise that most Norse place-names appear round the coast of Northern Britain. In general, island names ending in -aigh, -ey, -ay and -a are of Norse origin, reflecting the Norse word for island, øy. -

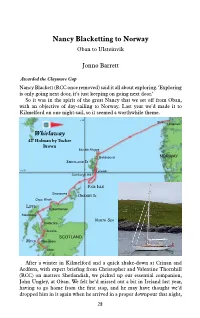

Nancy Blacketting to Norway Oban to Ulsteinvik

Nancy Blacketting to Norway Oban to Ulsteinvik Jonno Barrett Awarded the Claymore Cup Nancy Blackett (RCC once removed) said it all about exploring. ‘Exploring is only going next door, it’s just keeping on going next door.’ So it was in the spirit of the great Nancy that we set off from Oban, with an objective of day-sailing to Norway. Last year we’d made it to Kilmelford on one night-sail, so it seemed a worthwhile theme. 2 W Stad Ulsteinvik Whirlaway 42’ Holman by Tucker Brown Muckle Flugga Baltasound NORWAY SHETLAND IS 60 N Lerwick Sumburgh Hd FAIR ISLE Stromness ORKNEY IS Cape Wrath LEWIS Kinlochbervie Stornaway NORTH SEA Badachro Inverie SCOTLAND MUCK Tobermory Oban After a winter in Kilmelford and a quick shake-down at Crinan and Ardfern, with expert briefing from Christopher and Valentine Thornhill (RCC) on matters Shetlandish, we picked up our essential companion, John Ungley, at Oban. We felt he’d missed out a bit in Ireland last year, having to go home from the first stop, and he may have thought we’d dropped him in it again when he arrived in a proper downpour that night, 28 Nancy Blacketting to Norway and in Tobermory a day or two later; however, a dram is a wonderful waterproof. It cleared by lunch-time and we headed out to the Small Isles, making Bagh a Ghallanaich on Muck after an enjoyable reach, enjoying the first of a few special sunsets, this time over Rhum. Next day dawned fair but flat. More importantly, it was the day of the Brexit referendum, so hiding seemed appropriate. -

Sunderland Local Plan

Sutherland Local Plan Strategic Environmental Assessment Scoping Report April 2006 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The purpose of this Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) scoping report is to set out sufficient information on the Sutherland Local Plan to enable the Consultation Authorities to form a view on the consultation periods and the scope and level of detail that will be appropriate for the environmental report. 1.2 This report has been prepared in accordance with Regulation 17 of the Environmental Assessment of Plans and Programmes (Scotland) Regulations 2004. 1.3 The Highland Council is also preparing Local Plans for the Skye and Lochalsh and Lochaber areas. Separate scoping reports have been prepared for these plans, but it is intended that as far as possible, a consistent approach is taken both to the preparation of the plans and to the methodology and format of the strategic environmental assessment. 1.4 The Highland Council’s approach to carrying out the Strategic Environmental Assessment is based on the methodology developed whilst preparing the retrospective SEA for the Wester Ross Local Plan, in partnership with the Consultation Authorities. In addition to carrying out the SEA, The Council will also carry out a sustainability appraisal of the Local Plan, to balance environmental considerations with social and economic objectives. 1.5 For further information on the Sutherland Local Plan, please contact Brian Mackenzie on 01463 702276 ([email protected]) or Katie Briggs on 01463 702271 ([email protected]). 2. KEY FACTS Sutherland Local Plan 2.1 The Sutherland Local Plan area (see Map) extends over 6,071 square kilometres and is an area of high quality natural environment and diverse historical background. -

ASCOBANS Advisory Committee Meeting AC22/Inf.4.6.F the Hague, Netherlands, 29 September - 1 October 2015 Dist

22nd ASCOBANS Advisory Committee Meeting AC22/Inf.4.6.f The Hague, Netherlands, 29 September - 1 October 2015 Dist. 22 September 2015 Agenda Item 4.6 Review of New Information on Threats to Small Cetaceans Underwater Unexploded Ordnance Document Inf.4.6.f Investigation into the long-finned pilot whale mass stranding event, Kyle of Durness, 22nd July 2011 Action Requested Take note Submitted by CSIP NOTE: DELEGATES ARE KINDLY REMINDED TO BRING THEIR OWN COPIES OF DOCUMENTS TO THE MEETING Investigation into the long-finned pilot whale mass stranding event, Kyle of Durness, 22nd July 2011 Andrew Brownlow1, 9, Johanna Baily3, Mark Dagleish3, Rob Deaville2, Geoff Foster1, Silje-Kirstin Jensen7, Eva Krupp8, Robin Law6, Rod Penrose4, Matt Perkins2, Fiona Read5, Paul Jepson2 (1) SRUC Wildlife Unit, Drummondhill, Inverness, IV24JZ, UK (2) Institute of Zoology, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK; (3) Moredun Research Institute, Pentlands Science Park, Penicuik, Edinburgh EH26 0PZ, UK (4) Marine Environmental Monitoring, Penwalk, Llechryd, Cardigan, SA43 2PS, UK (5) University of Aberdeen, Zoology Department, Aberdeen, AB24 3UE (6 ) CEFAS Lowestoft Laboratory, Pakefield Road, Lowestoft, Suffolk, NR33 0HT, UK (7) Sea Mammal Research Unit, University of St. Andrews, Fife, KY16 8LB, UK (8) University of Aberdeen, Chemistry Department, Meston Walk, Aberdeen, AB24 3UE (9) Email: [email protected] Compiled by Andrew Brownlow, SRUC Wildlife Unit, Inverness 1 | P a g e Table of Contents ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 SECTION 1: STRANDING SUMMARY AND INVESTIGATION OUTLINE ............................................................................... 6 SECTION 2: ECOLOGY OF LONG-FINNED PILOT WHALES (GLOBICEPHALA MELAS) ............................................................. 7 SECTION 3: LONG-FINNED PILOT WHALE STRANDINGS IN SCOTLAND ........................................................................... -

2020 Annual Summary Report on the Results of the Shellfish

The Shellfish official control monitoring programmes for Scotland Summary report for 2020 Authors: Myriam Algoet(1), Lewis Coates(1), Sarah Swan(2), Lesley Bickerstaff(1), Charlotte Ford(1) and Sean Panton(3) (1) Cefas Laboratory, Barrack Road, Weymouth, Dorset, DT4 8UB (2) The Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS), Scottish Marine Institute, Oban, Argyll, PA37 1QA (3) Fera Science Ltd., National Agri-Food Innovation Campus, Sand Hutton, York, YO41 1LZ July 2021 © Crown copyright 2021 This information is licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications www.cefas.co.uk Cefas Document Control Submitted to: Graham Ewen, Food Standards Scotland (FSS) Date submitted: 15 July 2021 Project Manager: Karen Litster Myriam Algoet, based on input from Lewis Coates, Sarah Swan, Report compiled by: Lesley Bickerstaff, Charlotte Ford and Sean Panton Quality control by: Michelle Price-Hayward, 09 July 2021 Approved by and Karen Litster, 15 July 2021 date: Version: Final V1 Classification: Official Algoet, M., Coates L., Swan. S, Bickerstaff L., Ford C., Panton S. Recommended (2021). The Shellfish official control monitoring programmes for citation for this report: Scotland. Summary report for 2020. Cefas Project Report for FSS (Contract C7711/C7712/C7713/C7714/C7715), 38 pp. Version control history Version Author Date Comment Draft V1 M. Algoet, L. Coates, 24/06/2021 Submitted for S. Swan, L. accessibility check Bickerstaff, C. Ford, by Cefas S. Panton Communications team and to GM for QC Draft V2 M. Price-Hayward 09/07/2021 Quality controlled Draft V3 M. -

A New Stratigraphic Framework for the Early Neoproterozoic Successions of Scotland

Accepted Manuscript Journal of the Geological Society A new stratigraphic framework for the early Neoproterozoic successions of Scotland Maarten Krabbendam, Rob Strachan & Tony Prave DOI: https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2021-054 To access the most recent version of this article, please click the DOI URL in the line above. When citing this article please include the above DOI. Received 14 May 2021 Revised 19 August 2021 Accepted 23 August 2021 © 2021 UKRI. The British Geological Survey. Published by The Geological Society of London http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) Manuscript version: Accepted Manuscript This is a PDF of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting and correction before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. Although reasonable efforts have been made to obtain all necessary permissions from third parties to include their copyrighted content within this article, their full citation and copyright line may not be present in this Accepted Manuscript version. Before using any content from this article, please refer to the Version of Record once published for full citation and copyright details, as permissions may be required. Downloaded from http://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/jgs/article-pdf/doi/10.1144/jgs2021-054/5396122/jgs2021-054.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 A new stratigraphic framework for the early Neoproterozoic successions of Scotland Maarten Krabbendam1*, Rob Strachan2, Tony Prave3 1British Geological Survey, Lyell Centre, Research Avenue, Edinburgh EH14 4AP, Scotland, UK 2School of the Environment, Geography and Geosciences, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, PO1 3QL, UK. -

Natural Heritage Zones: a National Assessment of Scotland's

NATURAL HERITAGE ZONES: A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF SCOTLAND’S LANDSCAPES Contents Purpose of document 6 An introduction to landscape 7 The role of SNH 7 Landscape assessment 8 PART 1 OVERVIEW OF SCOTLAND'S LANDSCAPE 9 1 Scotland’s landscape: a descriptive overview 10 Highlands 10 Northern and western coastline 13 Eastern coastline 13 Central lowlands 13 Lowlands 13 2 Nationally significant landscape characteristics 18 Openness 18 Intervisibility 18 Naturalness 19 Natural processes 19 Remoteness 19 Infrastructure 20 3 Forces for change in the landscape 21 Changes in landuse (1950–2000) 21 Current landuse trends 25 Changes in development pattern 1950–2001 25 Changes in perception (1950–2001) 32 Managing landscape change 34 4 Landscape character: threats and opportunities 36 References 40 PART 2 LANDSCAPE PROFILES: A WORKING GUIDE 42 ZONE 1 SHETLAND 43 1 Nature of the landscape resource 43 2 Importance and value of the zone landscape 51 3 Landscape and trends in the zone 51 4 Building a sustainable future 53 ZONE 2 NORTH CAITHNESS AND ORKNEY 54 Page 2 11 January, 2002 1 Nature of the landscape resource 54 2 Importance and value of the zone landscape 72 3 Landscape and trends in the zone 72 4 Building a sustainable future 75 ZONE 3 WESTERN ISLES 76 1 Nature of the landscape resource 76 2 Importance and value of the zone landscape 88 3 Landscape and trends in the zone 89 4 Building a sustainable future 92 ZONE 4 NORTH WEST SEABOARD 93 1 Nature of the landscape resource 93 2 Importance and value of the zone landscape 107 3 Landscape and trends