Collapse of the Ruble Zone and Its Lessons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Číslo Ke Stažení V

Knihovna města Petřvald Foto Monika Molinková 4 MĚSÍČNÍK PRO KNIHOVNY Cena 40 Kč * * OBSAH MĚSÍČNÍK PRO KNIHOVNY 4 2015 ročník 67 FROM THE CONTENTS 123 ..... * TOPIC: National Digital Library – under the lid Luděk Tichý |123 * INTERVIEW with Vlastimil Vondruška, Czech writer and historian: 1 Pod pokličkou Národní digitální knihovny Vydává: “Books are written to please the readers, not the critics…” * Luděk Tichý Středočeská vědecká knihovna v Kladně, Lenka Šimková, Zuzana Mračková |125 příspěvková organizace Středočeského kraje, ..... * Klára’s cookbook or Ten recipes for library workshops: 125 ul. Generála Klapálka 1641, 272 01 Kladno „Knihy se nepíšou proto, aby se líbily literárním Non-fiction in museum sauce Klára Smolíková |129 * REVIEW: How philosopher Horáček came to Paseka publishers kritikům, ale čtenářům…“ Evid. č. časopisu MK ČR E 485 and what came of it Petr Nagy |131 * Lenka Šimková, Zuzana Mračková ISSN 0011-2321 (Print) ISSN 1805-4064 (Online) * INTERVIEW with PhDr. Dana Kalinová, World of Books Director: Šéfredaktorka: Mgr. Lenka Šimková Choosing from the range will be difficult again… Olga Vašková |133 ..... 129 Redaktorka: Bc. Zuzana Mračková * The future of public libraries in the Czech Republic in terms Grafická úprava a sazba: Kateřina Bobková of changes to the pensions system and social dialogue Poučné knížky v muzejní omáčce * Klára Smolíková Renáta Salátová |135 Sídlo redakce (příjem inzerce a objednávky na předplatné): * FROM ABROAD: The road to Latvia or Observations 131 ..... Středočeská vědecká knihovna v Kladně, from the Di-Xl conference Petr Schink |138 Kterak filozof Horáček k nakladatelství Paseka příspěvková organizace, Gen. Klapálka 1641, 272 01 Kladno * The world seen very slowly by Jan Drda Naděžda Čížková |142 přišel a co z toho vzešlo * Petr Nagy Tel.: 312 813 154 (Lenka Šimková) * FROM THE TREASURES… of the West Bohemian Museum Library Tel.: 312 813 138 (Bc. -

Russia's 2020 Strategic Economic Goals and the Role of International

Russia’s 2020 Strategic Economic Goals and the Role of International Integration 1800 K Street NW | Washington, DC 20006 Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org authors Andrew C. Kuchins Amy Beavin Anna Bryndza project codirectors Andrew C. Kuchins Thomas Gomart july 2008 europe, russia, and the united states ISBN 978-0-89206-547-9 finding a new balance Ë|xHSKITCy065479zv*:+:!:+:! CENTER FOR STRATEGIC & CSIS INTERNATIONAL STUDIES Russia’s 2020 Strategic Economic Goals and the Role of International Integration authors Andrew C. Kuchins Amy Beavin Anna Bryndza project codirectors Andrew C. Kuchins Thomas Gomart july 2008 About CSIS In an era of ever-changing global opportunities and challenges, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) provides strategic insights and practical policy solutions to decisionmakers. CSIS conducts research and analysis and develops policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke at the height of the Cold War, CSIS was dedicated to the simple but urgent goal of finding ways for America to survive as a nation and prosper as a people. Since 1962, CSIS has grown to become one of the world’s preeminent public policy institutions. Today, CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, DC. More than 220 full- time staff and a large network of affiliated scholars focus their expertise on defense and security; on the world’s regions and the unique challenges inherent to them; and on the issues that know no boundary in an increasingly connected world. -

United Nations/Russian Federation Workshop on the Applications of Global Navigation Satellite Systems

United Nations/Russian Federation Workshop on the Applications of Global Navigation Satellite Systems Organized jointly by the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs and the Russian Federal Space Agency (ROSCOSMOS) Co-organized by the International Committee on Global Navigation Satellite Systems Hosted by the Reshetven Information Satellite Systems (ISS) Joint Stock Company Krasnoyarsk, Russian Federation 18 - 22 May 2015 1. Venue of the Workshop The Workshop will be held at: Hotel Siberia International Exhibition Business Centre (IEBC) Address: Aviatorov Street 19, 660077 Business Centre Krasnoyarsk, Russia Telephone: +391 298 90 50 Fax: +391 298 90 51 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.centersiberia.ru/ 2. Local Organizing Committee in Krasnoyarsk The Workshop is hosted by the Reshetnev ISS Joint Stock Company in Krasnoyarsk, Russian Federation. The contact person is Mr. Vassili ZVONAR, Head of Department Navigation & Geodesy, Space Systems and Satellites Design. Address: 52 Lenin St. Zheleznogorsk, Krasnoyarsky Region, 662972, Russia Tel.: +(3919)76 42 99 Fax: +(3919)75 61 46 / 75 20 32 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.iss-reshetnev.com Page 1 of 4 3. Arriving to Krasnoyarsk Yemelyanovo international airport is the main airport of the city of Krasnoyarsk. The airport is located 27 kilometers west of the city, and 10 kilometers from the federal highway М-53. Information about the airport could be found at http://www.yemelyanovo.ru/en/. Workshop participants will be met at the airport by a representative of the Local Organizing Committe. All participants will be provided a shuttle service from the airport to Hotel IEBC. -

Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section___Focus Question

Name ______________________ Date ___________ Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section__________ Focus Question: What were Reaganʼs foreign policies and how did they contribute to the fall of communism in Europe? President Reagan believed that Peace would come through strength rather than the policy of détente. He also believed that the US had to challenge communism to weaken it. How would he do this? 1. Build up military-new nuclear weapons 2. Support and aid anti-communists around the world A. Reagan builds up the military. 1. largest peacetime military build up 2. Billions of dollars to development and productions of new weapons, B1, B-2 bombers, MX missile system 3. Reagan knew the economy of Soviet Union could not support massive military build up 4. Strategic Defense Initiative/Star Wars—land and space lasers would destroy any missile aimed at US before it hit its target B. Reagan aids and supports anti-communists around the world 1. Afghanistan --- 1979 Soviet Union invades Afghanistan US funded and trained the Mujahadeen (guerilla forces on holy mission for Allah). Soviets begin to pull out 1988 2. Grenada --- small island nation in Caribbean Government taken over by radicals aided by Cuba US invades to keep Granada from becoming Communist outpost and to help Medical students there. 3. El Salvador --- US supports a right wing (less government control of people) government. Congress said the government there “rotten” and US should not aid. Decided aid dependent on government making progress with human rights 4. Nicaragua --- New Government, Sandanistas in control, socialist form of govt. -

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation J. MICHAEL WALLER "They write I'm the mafia's godfather. It was Vladimir Ilich Lenin who was the real organizer of the mafia and who set up the criminal state." -Otari Kvantrishvili, Moscow organized crime leader.l "Criminals Nave already conquered the heights of the state-with the chief of the KGB as head of a mafia group." -Former KGB Maj. Gen. Oleg Kalugin.2 Introduction As the United States and Russia launch a Great Crusade against organized crime, questions emerge not only about the nature of joint cooperation, but about the nature of organized crime itself. In addition to narcotics trafficking, financial fraud and racketecring, Russian organized crime poses an even greater danger: the theft and t:rafficking of weapons of mass destruction. To date, most of the discussion of organized crime based in Russia and other former Soviet republics has emphasized the need to combat conven- tional-style gangsters and high-tech terrorists. These forms of criminals are a pressing danger in and of themselves, but the problem is far more profound. Organized crime-and the rarnpant corruption that helps it flourish-presents a threat not only to the security of reforms in Russia, but to the United States as well. The need for cooperation is real. The question is, Who is there in Russia that the United States can find as an effective partner? "Superpower of Crime" One of the greatest mistakes the West can make in working with former Soviet republics to fight organized crime is to fall into the trap of mirror- imaging. -

Yeltsin's Winning Campaigns

7 Yeltsin’s Winning Campaigns Down with Privileges and Out of the USSR, 1989–91 The heresthetical maneuver that launched Yeltsin to the apex of power in Russia is a classic representation of Riker’s argument. Yeltsin reformulated Russia’s central problem, offered a radically new solution through a unique combination of issues, and engaged in an uncompro- mising, negative campaign against his political opponents. This allowed Yeltsin to form an unusual coalition of different stripes and ideologies that resulted in his election as Russia’s ‹rst president. His rise to power, while certainly facilitated by favorable timing, should also be credited to his own political skill and strategic choices. In addition to the institutional reforms introduced at the June party conference, the summer of 1988 was marked by two other signi‹cant developments in Soviet politics. In August, Gorbachev presented a draft plan for the radical reorganization of the Secretariat, which was to be replaced by six commissions, each dealing with a speci‹c policy area. The Politburo’s adoption of this plan in September was a major politi- cal blow for Ligachev, who had used the Secretariat as his principal power base. Once viewed as the second most powerful man in the party, Ligachev now found himself chairman of the CC commission on agriculture, a position with little real in›uence.1 His ideological portfo- lio was transferred to Gorbachev’s ally, Vadim Medvedev, who 225 226 The Strategy of Campaigning belonged to the new group of soft-line reformers. His colleague Alexan- der Yakovlev assumed responsibility for foreign policy. -

Soviet Ruble, Gold Ruble, Tchernovetz and Ruble-Merchandise Mimeograph

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt258032tg No online items Overview of the Soviet ruble, gold ruble, tchernovetz and ruble-merchandise mimeograph Processed by Hoover Institution Archives Staff. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2009 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Overview of the Soviet ruble, YY497 1 gold ruble, tchernovetz and ruble-merchandise mimeograph Overview of the Soviet ruble, gold ruble, tchernovetz and ruble-merchandise mimeograph Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Hoover Institution Archives Staff Date Completed: 2009 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from MARC record by David Sun. © 2009 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Soviet ruble, gold ruble, tchernovetz and ruble-merchandise mimeograph Dates: 1923 Collection Number: YY497 Collection Size: 1 item (1 folder) (0.1 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Relates to the circulation of currency in the Soviet Union. Original article published in Agence économique et financière, 1923 July 18. Translated by S. Uget. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: English Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all audiovisual material is immediately accessible. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. -

Russian America and the USSR: Striking Parallels by Andrei V

Russian America and the USSR: Striking Parallels by Andrei V. Grinëv Translated by Richard L. Bland Abstract. The article is devoted to a comparative analysis of the socioeconomic systems that have formed in the Russian colonies in Alaska and in the USSR. The author shows how these systems evolved and names the main reason for their similarity: the nature of the predominant type of property. In both systems, supreme state property dominated and in this way they can be designated as politaristic. Politariasm (from the Greek πολιτεία—the power of the majority, that is, in a broad sense, the state, the political system) is formation founded on the state’s supreme ownership of the basic means of production and the work force. Economic relations of politarism generated the corresponding social structure, administrative management, ideological culture, and even similar psychological features in Russian America and the USSR. Key words: Russian America, USSR, Alaska, Russian-American Company, politarism, comparative historical research. The selected theme might seem at first glance paradoxical. And in fact, what is common between the few Russian colonies in Alaska, which existed from the end of the 18th century to 1867, and the huge USSR of the 20th century? Nevertheless, analysis of this topic demonstrates the indisputable similarity between the development of such, it would seem, different-scaled and diachronic socioeconomic systems. It might seem surprising that many phenomena of the economic and social sphere of Russian America subsequently had clear analogies in Soviet society. One can hardly speak of simple coincidences and accidents of history. Therefore, the selected topic is of undoubted scholarly interest. -

Economy of Uzbekistan

Economy of Uzbekistan Since gaining independence, the has stated that it is committed to a gradual transition to a market-based economy. The progress with economic Economy of Uzbekistan policy reforms has been a cautious one, but cumulatively Uzbekistan has shown respectable achievements. The government is yet to eliminate the gap between the black market and official exchange rates by successfully introducing convertibility of the national currency. Its restrictive trade regime and generally interventionist policies continue to have a negative effect on the economy. Substantial structural reform is needed, particularly in these areas: improving the investment climate for foreign investors, strengthening the banking system, and freeing the agricultural sector from state control. Remaining restrictions on currency conversion capacity and other government measures to control economic activity, including the implementation of severe import restrictions and sporadic closures of Uzbekistan's borders with neighboring Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan have led international lending organizations to suspend or scale back credits. Working closely with the IMF, the government has made considerable progress in reducing inflation and the budget deficit. The national currency was made convertible in 2003 as part of the IMF-engineered stabilization program, although some administrative restrictions remain. The Commercial buildings in Tashkent [3] agriculture and manufacturing industries contribute equally to the economy, each accounting for about one-quarter of the GDP. Uzbekistan is a Fixed 1 soʻm (UZS) = major producer and exporter of cotton, although the importance of this commodity has declined significantly since the country achieved exchange rates 100 tiyin independence.[4] Uzbekistan is also a big producer of gold, with the largest open-pit gold mine in the world. -

Maximum Monthly Stipend Rates For

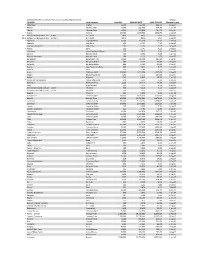

MAXIMUM MONTHLY STIPEND RATES FOR FELLOWS AND SCHOLARS Jul 2020 COUNTRY Local Currency Local DSA MAX RES RATE MAX TRV RATE Effective % date * Afghanistan Afghani 12,600 132,300 198,450 1-Aug-07 * Albania Albania Lek(e) 14,000 220,500 330,750 1-Jan-05 Algeria Algerian Dinar 31,600 331,800 497,700 1-Aug-07 * Angola Kwanza 133,000 1,396,500 2,094,750 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Apr. - 30 Nov.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Dec. - 31 Mar.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 * Argentina Argentine Peso 18,600 153,450 230,175 1-Jan-05 Australia AUL Dollar 453 4,757 7,135 1-Aug-07 Australia - Academic AUL Dollar 453 1,200 7,135 1-Aug-07 * Austria Euro 261 2,741 4,111 1-Aug-07 * Azerbaijan (new)Azerbaijan Manat 239 1,613 2,420 1-Jan-05 Bahrain Bahraini Dinar 106 2,226 3,180 1-Jan-05 Bahrain - Academic Bahraini Dinar 106 1,113 1,670 1-Aug-07 Bangladesh Bangladesh Taka 12,400 130,200 195,300 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 * Belarus New Belarusian Ruble 600 5,850 8,775 1-Jan-06 Belgium Euro 338 3,549 5,324 1-Aug-07 Benin CFA Franc(XOF) 123,000 1,291,500 1,937,250 1-Aug-07 Bhutan Bhutan Ngultrum 7,290 76,545 114,818 1-Aug-07 * Bolivia Boliviano 1,200 10,800 16,200 1-Jan-07 * Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Mark 279 3,557 5,336 1-Jan-05 Botswana Botswana Pula 2,220 23,310 34,965 1-Aug-07 Brazil Brazilian Real 530 4,373 6,559 1-Jan-05 British Virgin Islands (16 Apr. -

The Monetary Legacy of the Soviet Union / Patrick Conway

ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE are published by the International Finance Section of the Department of Economics of Princeton University. The Section sponsors this series of publications, but the opinions expressed are those of the authors. The Section welcomes the submission of manuscripts for publication in this and its other series. Please see the Notice to Contributors at the back of this Essay. The author of this Essay, Patrick Conway, is Professor of Economics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has written extensively on the subject of structural adjustment in developing and transitional economies, beginning with Economic Shocks and Structural Adjustment: Turkey after 1973 (1987) and continuing, most recently, with “An Atheoretic Evaluation of Success in Structural Adjustment” (1994a). Professor Conway has considerable experience with the economies of the former Soviet Union and has made research visits to each of the republics discussed in this Essay. PETER B. KENEN, Director International Finance Section INTERNATIONAL FINANCE SECTION EDITORIAL STAFF Peter B. Kenen, Director Margaret B. Riccardi, Editor Lillian Spais, Editorial Aide Lalitha H. Chandra, Subscriptions and Orders Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conway, Patrick J. Currency proliferation: the monetary legacy of the Soviet Union / Patrick Conway. p. cm. — (Essays in international finance, ISSN 0071-142X ; no. 197) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-88165-104-4 (pbk.) : $8.00 1. Currency question—Former Soviet republics. 2. Monetary policy—Former Soviet republics. 3. Finance—Former Soviet republics. I. Title. II. Series. HG136.P7 no. 197 [HG1075] 332′.042 s—dc20 [332.4′947] 95-18713 CIP Copyright © 1995 by International Finance Section, Department of Economics, Princeton University. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic