Falling Mythologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

Northridge Review

Northridge Review Spring 2013 Acknowledgements The Northridge Review gratefully acknowledges the Associated Students of CSUN and the English Department faculty and staff,Frank De La Santo, Marjie Seagoe, Tonie Mangum, and Marleene Cooksey for all their help. Submission Information The N orthridge Review accepts submissions of fiction, creative nonfiction, poetry, drama, and art throughout the year. The Northridge Review has recently changed the submission process. Manuscripts can be uploaded to the following page: http://thenorthridgereview.submittable.com/submit Submissions should be accompanied by a cover page that includes the writer's name, address, email, and phone number, as well as the titles of the works submitted. The writer's name should not appear on the manu script itself. Printed manuscripts and all other correspondence can still be delivered to the following address: Northridge Review Department of English California State University Northridge 18111 NordhoffSt. Northridge, CA 91330-8248 Staff Chief Editor Faculty Advisor Karlee Johnson Mona Houghton Poetry Editors Fiction Editor ltiola "Stephanie"Jones Olvard Smith Nicole Socala Fiction Board Poetry Board Aliou Amravanti Kashka Mandela Anna Austin Brown-Burke Jasmine Adame Alexandra Johnson KyleLifton Karlee Johnson Marcus Landon Saman Kangarloo Khiem N gu.yen Kristina Kolesnyk Evon Magana Business Manager Rich McGinis Meaghan Gallagher Candice Montgomery Emily Robles Business Board Alexandra Johnson Layout and Design Editor Karlee Johnson A[iou Amravanti Kashka Mandela ltiola "Stephanie" Jones Brown-Burke Saman Kangarloo Layout and Design Board Desktop Publishing Editors Jasmine Adame Marcus Landon Anna Austin Emily Robles Kyle Lifton Evon Magana Desktop Publishing Board Khiem Nguyen KristinaKolesrryk O[vard Smith Rich McGinis Nicole Socala Candice Montgomery Awards The Northridge Review Fiction Award, given annually, recognizes excel lent fiction by a CSUN student published in the Northridge Review. -

Thomas Mann and Franz Kafka

The Magician9sModem Avatars: A Study of the Artist Figure in the Works of Marcel Proust, Thomas Mann and Franz Kafka Ramona M. Uritescu Graduate Program in Comparative Literature Submitted in partial fidf3ment of the requîrernents for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Graduate Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario August 1998 O Ramona M. Untescu 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale (Sfl of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KtA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, districbute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de rnicrofiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retaîns ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be prînted or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent êeimprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son pexmïssion. autorisation. ABSTRACT Adapting the figure of the Renaissance magician, 1 argue that it is a fitting metaphor for the modem artist/writer. Both the magus and the writer perform an act of mediation between two ontological levels and constitute, as a result, unique gates of access to "the beyond." That is why they cm both be associated with the kind of deception specitic to charlatanism and why they represent a different kind of morality that renders acts of voyeurism and profanation necessary. -

Women Singer-Songwriters As Exemplary Actors: the Music of Rape and Domestic Violence

Women Singer-Songwriters as Exemplary Actors: The Music of Rape and Domestic Violence KATHANNE W. GREENE At the 2016 Oscars, Lady Gaga, joined onstage by fifty rape survivors, performed the song “Til It Happens to You.” The Oscar-nominated song by Lady Gaga and Diane Warren was written for The Hunting Ground, a documentary film about campus sexual assault. Over thirty-one million people viewed the Oscar performance, which brought some in the audience to tears, and the video on Vevo has received over twenty-nine million views with another twenty-eight million views on YouTube. The film, video, and performance are the result of a growing political and social movement by young high school and college women to force schools, universities, and colleges to vigorously respond to rape and sexual harassment on campus. In response to complaints filed by more and more young women, the Obama Administration and the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) in the Department Education began investigating claims that schools, colleges, and universities were not actively and adequately responding to claims of sexual assault and harassment despite passage of the Clery Act of 1990. The Clery Act requires colleges and universities to report data on crime on campus, provide support and accommodations to survivors, and establish written policies and procedures for the handling of campus crime.1 Since 2011, the OCR has expanded its efforts to address sexual assault on campuses as violations of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 that prohibits sex discrimination -

La Lorraine Artiste: Nature, Industry, and the Nation in the Work of Émile Gallé and the École De Nancy

La Lorraine Artiste: Nature, Industry, and the Nation in the Work of Émile Gallé and the École de Nancy By Jessica Marie Dandona A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Chair Professor Anne Wagner Professor Andrew Shanken Spring 2010 Copyright © 2010 by Jessica Marie Dandona All rights reserved Abstract La Lorraine Artiste: Nature, Industry, and the Nation in the Work of Émile Gallé and the École de Nancy by Jessica Marie Dandona Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Chair My dissertation explores the intersection of art and politics in the career of 19th-century French designer Émile Gallé. It is commonly recognized that in fin-de-siècle France, works such as commemorative statues and large-scale history paintings played a central role in the creation of a national mythology. What has been overlooked, however, is the vital role that 19th-century arts reformers attributed to material culture in the process of forming national subjects. By educating the public’s taste and promoting Republican values, many believed that the decorative arts could serve as a powerful tool with which to forge the bonds of nationhood. Gallé’s works in glass and wood are the product of the artist’s lifelong struggle to conceptualize just such a public role for his art. By studying decorative art objects and contemporary art criticism, then, I examine the ways in which Gallé’s works actively participated in contemporary efforts to define a unified national identity and a modern artistic style for France. -

Go Home Seth Price

Go Home Seth Price To execute the piece: 1. Print out these pages. 2. Using tape, arrange them on the wall such that they form a road that appears to lead away from the viewer. 1. Central African Republic By Ed p. 2 2. Saudi Arabia By Cristy 6 3. Nepal By Mike 34 4. Iraq By Julie 36 5. Israel, the West Bank and Gaza- By JFED students 40 6. Indonesia By Andrea and Dale 46 7. Haiti By Dan 54 8. Algeria By Patrice 98 9. Libya By Geoff and John 103 10. Colombia By Rick 110 11. Afghanistan By Christine 131 12. Cote d’Ivoire By Kristin 136 13. Pakistan By Erik 140 14. Democratic Republic of the Congo By rschuh23 158 15. Zimbabwe By Jason 159 16. Liberia By Marcy 162 17. Nigeria By Louise 164 18. Lebanon By anonymous 168 19. Sudan By Sally 181 20. Bosnia By Josh 185 21. Somalia By adam911 201 22. Angola By Sue and Jeri 202 23. Kenya By labonnecuisine 208 24. Yemen By Tim 210 25. Burundi By Jonathan 217 26. Iran By Patrick 226 http://www.balloonlife.com/publications/balloon_life/9605/breakfas.htm Breakfast On The Verandah - African Style by Ed Heltshe ------------------------------------------------------------------------ The monkeys took our bananas... The British took our beer... African pilot Jim Seton-Rodgers took first place. Balloon racing in Zimbabwe confirmed for me the south central African republic’s self proclaimed status as "Africa’s Paradise." Together with fellow pilots, Susan and Peter Stamats of Cedar Rapids, Iowa in a Flamboyant Balloons 105 generously provided by the legendary Terry Adams of Johannesburg South Africa, I had the opportunity to really experience both the geographical wonders of Zimbabwe and the equally remarkable hospitality of the local inhabitants. -

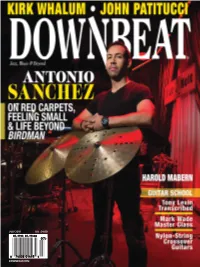

Downbeat.Com July 2015 U.K. £4.00

JULY 2015 2015 JULY U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT ANTONIO SANCHEZ • KIRK WHALUM • JOHN PATITUCCI • HAROLD MABERN JULY 2015 JULY 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Music Volume 1 of 2 Phono-somatics: gender, embodiment and voice in the recorded music of Tori Amos, Björk and PJ Harvey by Sarah Boak Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2015 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Music Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy PHONO-SOMATICS: GENDER, EMBODIMENT AND VOICE IN THE RECORDED MUSIC OF TORI AMOS, BJÖRK AND PJ HARVEY Sarah Boak This thesis is a feminist enquiry into the relationship between gender, embodiment and voice in recorded popular music post-1990. In particular, the study focuses on the term ‘embodiment’ and defines this term in a way that moves forward from a simple understanding of representing the body in music. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

American Romanticism

PART –-----–– Individualism and Nature Kindred Spirits, 1849. Asher Durand. Oil on canvas. The New York Public Library. “We see the world piece by piece, as the sun, the moon, the animal, the tree; but the whole, of which these are the shining parts, is the soul.” —Emerson, “The Over-Soul” 177 Francis G. Mayer/CORBIS 0177 U2P1-845481.indd 177 4/11/06 3:46:04 PM BEFORE YOU READ from Nature, from Self-Reliance, and Concord Hymn MEET RALPH WALDO EMERSON alph Waldo Emerson was the central figure of American Romanticism. His ideas about Rthe individual, claims about the divine, and attacks on society were revolutionary. Emerson’s father was a Unitarian minister and his mother a devout Anglican. When Emerson was only eight years old, his father died, and Mrs. Emerson was forced to open a boarding- house. At the age of 14, Emerson entered Harvard College. After graduation, he studied at Harvard Divinity School. By 1829, Emerson had been ordained a Unitarian minister and was preaching in Boston’s Second Church. Challenges to Optimism Emerson’s own opti- In 1831 Ellen Tucker, Emerson’s wife, died sud- mism was challenged when his son Waldo died of denly. Emerson had already been questioning his scarlet fever in 1842. Two years later, Emerson’s religious convictions, and after Ellen’s death, he essay “The Tragic” appeared in The Dial, a tran- experienced intense grief that further eroded his scendentalist magazine he had co-founded. In this faith. Eventually, Emerson left the church to essay, Emerson claimed that the arts and the intel- embark on a career as a writer. -

Roland 2016 HHTFIN.Pdf

Mighty Oaks from Little Acorns Grow: The Role of the Vanderbilt Aid Society in the Establishment and Development of Vanderbilt University, 1894-1930. By Charlotte Roland Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of History of Vanderbilt University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For Honors in History April 2016 On the basis of this thesis defended by the candidate on ______________________________ we, the undersigned, recommend that the candidate be awarded_______________________ in History. __________________________________ Director of Honors – Samira Sheikh ___________________________________ Faculty Adviser – Christopher Loss ___________________________________ Third Reader – Paul Kramer Table of Contents Introduction: “Let us be in a position to furnish aid”: An 1-17 Introduction to the Vanderbilt Aid Society Chapter One: “The true function of student aid is to aid”: The 18-39 Vanderbilt Aid Society in Aid of Vanderbilt University’s Educational Mission Chapter Two: “How shall a man get his education when he cannot 40-60 pay for it from his own means?”: The Vanderbilt Aid Society as a Progressive Society Chapter Three: “A club is an assembly of good fellows meeting 61-82 under certain conditions”: The Vanderbilt Aid Society as a Women’s Aid Society Conclusion: “Bearing fruit many fold”: A Conclusion to the Aid 83-88 Society Bibliography 89-98 “Let us be in a position to furnish aid” An Introduction to the Vanderbilt Aid Society In 2009, Morel Enoch Harvey, then president of the Vanderbilt Aid Society, led the group of women in one final vote: the vote to disband.1 Founded in 1894, the nineteenth-century group felt itself growing out of place within the twenty-first century goals of Vanderbilt University. -

“Don't You Realize It's Just Her Disguise?”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives “Don’t you realize it’s Just Her Disguise?” Performances of femininity by Kim Gordon, Tori Amos and Gillian Welch Tonje Håkensen Master Thesis Institute of Musicology University of Oslo February 2007 Preface Both popular music and femininity is something I deal with everyday, yet it has been quite challenging to write about it. I have been able to do so because of the following people: My tutor, Stan Hawkins: Your commentary is always inspiring, helpful and very interesting. It’s been so much fun working with you. I am deeply grateful. My wonderful and supportive family; Solvor Sperati Karlsen, Terje “8-timers-dagen” Håkensen, Daniel Håkensen, Michelle Schachtler and Marit Håkensen. My equally wonderful and supportive friends, I can’t mention any names because I’m afraid I’ll leave somebody out. My dear Bjørnar Sund, I’m looking forward to discussing this thesis with you. All fellow students at IMV, especially the “class of 2002” and those I have worked with in Fagutvalget/Programutvalget, thank you for collaboration and fun. Guro Flinterud and Ingvil Urdal, this thesis is for you. Oslo, January 2007 Tonje Håkensen. Contents Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….. i Chapter 1: Introduction …………………………………………………………………1 Choice of Objects………………………………………………………………………… 2 Structure…………………………………………………………………………………...3 Meaning and Dialogue…………………………………………………………………….4 My position on Popular Musicology………………………………………………………5 Femininity and Music……………………………………………………………………...6 Gender and Musicology………………………………………………………………….. 10 Performance……………………………………………………………………………….14 Performance and Authorship……………………………………………………………...15 Authorship, Authenticity and Gender …………………………………………………….18 Situation…………………………………………………………………………………...20 Chapter 2: Smartest Girl on the Strip ………………………………………………….