“Don't You Realize It's Just Her Disguise?”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

{Download PDF} Goodbye 20Th Century: a Biography of Sonic

GOODBYE 20TH CENTURY: A BIOGRAPHY OF SONIC YOUTH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Browne | 464 pages | 02 Jun 2009 | The Perseus Books Group | 9780306816031 | English | Cambridge, MA, United States SYR4: Goodbye 20th Century - Wikipedia He was also in the alternative rock band Sonic Youth from until their breakup, mainly on bass but occasionally playing guitar. It was the band's first album following the departure of multi-instrumentalist Jim O'Rourke, who had joined as a fifth member in It also completed Sonic Youth's contract with Geffen, which released the band's previous eight records. The discography of American rock band Sonic Youth comprises 15 studio albums, seven extended plays, three compilation albums, seven video releases, 21 singles, 46 music videos, nine releases in the Sonic Youth Recordings series, eight official bootlegs, and contributions to 16 soundtracks and other compilations. It was released in on DGC. The song was dedicated to the band's friend Joe Cole, who was killed by a gunman in The lyrics were written by Thurston Moore. It featured songs from the album Sister. It was released on vinyl in , with a CD release in Apparently, the actual tape of the live recording was sped up to fit vinyl, but was not slowed down again for the CD release. It was the eighth release in the SYR series. It was released on July 28, The album was recorded on July 1, at the Roskilde Festival. The album title is in Danish and means "Other sides of Sonic Youth". For this album, the band sought to expand upon its trademark alternating guitar arrangements and the layered sound of their previous album Daydream Nation The band's songwriting on Goo is more topical than past works, exploring themes of female empowerment and pop culture. -

SST Defies Industry, Defines New Music

Page 1 The San Diego Union-Tribune October 1, 1995 Sunday SST Defies Industry, Defines New Music By Daniel de Vise KNIGHT-RIDDER NEWSPAPERS DATELINE: LOS ALAMITOS, CALIF. Ten years ago, when SST Records spun at the creative center of rock music, founder Greg Ginn was living with six other people in a one-room rehearsal studio. SST music was whipping like a sonic cyclone through every college campus in the country. SST bands criss-crossed the nation, luring young people away from arenas and corporate rock like no other force since the dawn of punk. But Greg Ginn had no shower and no car. He lived on a few thousand dollars a year, and relied on public transportation. "The reality is not only different, it's extremely, shockingly different than what people imagine," Ginn said. "We basically had one place where we rehearsed and lived and worked." SST, based in the Los Angeles suburb of Los Alamitos, is the quintessential in- dependent record label. For 17 years it has existed squarely outside the corporate rock industry, releasing music and spoken-word performances by artists who are not much interested in making money. When an SST band grows restless for earnings or for broader success, it simply leaves the label. Founded in 1978 in Hermosa Beach, Calif., SST Records has arguably produced more great rock bands than any other label of its era. Black Flag, fast, loud and socially aware, was probably the world's first hardcore punk band. Sonic Youth, a blend of white noise and pop, is a contender for best alternative-rock band ever. -

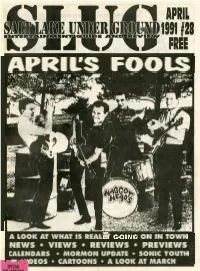

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

ISSUE 1820 AUGUST 17, 1990 BREATHE "Say Aprayer"9-4: - the New Single

ISSUE 1820 AUGUST 17, 1990 BREATHE "say aprayer"9-4: - the new single. Your prayers are answered. Breathe's gold debut album All That Jazz delivered three Top 10 singles, two #1 AC tracks, and songwriters David Glasper and Marcus Lillington jumped onto Billboard's list of Top Songwriters of 1989. "Say A Prayer" is the first single from Breathe's much -anticipated new album Peace Of Mind. Produced by Bob Sargeant and Breathe Mixed by Julian Mendelsohn Additional Production and Remix by Daniel Abraham for White Falcon Productions Management: Jonny Too Bad and Paul King RECORDS I990 A&M Record, loc. All rights reserved_ the GAVIN REPORT GAVIN AT A GLANCE * Indicates Tie MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MICHAEL BOLTON JOHNNY GILL MICHAEL BOLTON MATRACA BERG Georgia On My Mind (Columbia) Fairweather Friend (Motown) Georgia On My Mind (Columbia) The Things You Left Undone (RCA) BREATHE QUINCY JONES featuring SIEDAH M.C. HAMMER MARTY STUART Say A Prayer (A&M) GARRETT Have You Seen Her (Capitol) Western Girls (MCA) LISA STANSFIELD I Don't Go For That ((west/ BASIA HANK WILLIAMS, JR. This Is The Right Time (Arista) Warner Bros.) Until You Come Back To Me (Epic) Man To Man (Warner Bros./Curb) TRACIE SPENCER Save Your Love (Capitol) RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RIGHTEOUS BROTHERS SAMUELLE M.C. HAMMER MARTY STUART Unchained Melody (Verve/Polydor) So You Like What You See (Atlantic) Have You Seen Her (Capitol) Western Girls (MCA) 1IrPHIL COLLINS PEBBLES ePHIL COLLINS goGARTH BROOKS Something Happened 1 -

Pender Humane Society and Their Phone 910-937-1164 Or 910-455-0182

Expanding Families One Pet at a Time July 2017 Priceless TM Celebrating the Bond Between Humans and Animals PawPrints Magazine's Homeless cover Model Summertime is here and that can only mean one thing… it’s Kitten Season! Across the nation, millions of kittens are being born and are waiting for loving homes. My name is Elmer and Photo by: Michael Cline Photography I’m one such kitten. I was once sitting at Brunswick County Animal Control, but Adopt-An-ANGEL found me and took me in. Did you know they have over ONE HUNDRED kittens in their foster care program right now? Kittens just as precious as me, in all colors, sizes and shapes. I’m just 10-weeks-old and simply adorable. I love to play with toys, but I will also curl up happily on your chest and fall fast asleep. If you’d like to give me a loving home, please call my Adopt-An-ANGEL foster mom at 910-471-6909. She can also tell you about the other kittens up for adoption. And don’t forget, your county’s Animal Control is full of kittens too, so please visit and please look through this magazine at all the kittens pictured. There is someone for everyone! I’d now like to thank Michael Cline Photography for capturing my kittenish charm in my fruit-tastic cover photo and in the patriotic photo above. Being a cover model is quite exciting, but I’d much rather be someone’s beloved family member. “IF YOUR DOG IS NOT COMING TO YOU… YOU SHOULD BE COMING TO US!” Classes begin July 31st $10.00 off with this ad (first time students only) Not for profit service organization since 1971 910-392-2040 Visit our website at www.adtc.us Looking for the Hi, my name is Alice perfect house (35608354) and I’m a companion? One Patchwork Siamese who is small and girl. -

The Menstrual Cramps / Kiss Me, Killer

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 279 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2018 “What was it like getting Kate Bush’s approval? One of the best moments ever!” photo: Oli Williams CANDYCANDY SAYSSAYS Brexit, babies and Kate Bush with Oxford’s revitalised pop wonderkids Also in this issue: Introducing DOLLY MAVIES Wheatsheaf re-opens; Cellar fights on; Rock Barn closes plus All your Oxford music news, previews and reviews, and seven pages of local gigs for October NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk host a free afternoon of music in the Wheatsheaf’s downstairs bar, starting at 3.30pm with sets from Adam & Elvis, Mark Atherton & Friends, Twizz Twangle, Zim Grady BEANIE TAPES and ALL WILL BE WELL are among the labels and Emma Hunter. releasing new tapes for Cassette Store Day this month. Both locally- The enduring monthly gig night, based labels will have special cassette-only releases available at Truck run by The Mighty Redox’s Sue Store on Saturday 13th October as a series of events takes place in record Smith and Phil Freizinger, along stores around the UK to celebrate the resurgence of the format. with Ainan Addison, began in Beanie Tapes release an EP by local teenage singer-songwriter Max October 1991 with the aim of Blansjaar, titled `Spit It Out’, as well as `Continuous Play’, a compilation recreating the spirit of free festivals of Oxford acts featuring 19 artists, including Candy Says; Gaz Coombes; in Oxford venues and has proudly Lucy Leave; Premium Leisure and Dolly Mavies (pictured). -

Body in the Lyrics of Tori Amos

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 3-2014 "Purple People": "Sexed" Linguistics, Pleasure, and the "Feminine" Body in the Lyrics of Tori Amos Megim A. Parks California State University - San Bernardino Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Parks, Megim A., ""Purple People": "Sexed" Linguistics, Pleasure, and the "Feminine" Body in the Lyrics of Tori Amos" (2014). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 5. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/5 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “PURPLE PEOPLE”: “SEXED” LINGUISTICS, PLEASURE, AND THE “FEMININE” BODY IN THE LYRICS OF TORI AMOS ______________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino ______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition ______________________ by Megim Alexi Parks March 2014 “PURPLE PEOPLE”: “SEXED” LINGUISTICS, PLEASURE, AND THE “FEMININE” BODY IN THE LYRICS OF TORI AMOS ______________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino ______________________ by Megim Alexi Parks March 2014 ______________________ Approved by: Dr. Jacqueline Rhodes, Committee Chair, English Dr. Caroline Vickers, Committee Member Dr. Mary Boland, Graduate Coordinator © 2014 Megim Alexi Parks ABSTRACT The notion of a “feminine” style has been staunchly resisted by third-wave feminists who argue that to posit a “feminine” style is essentialist. -

Ann Powers YOU BETTER THINK

Ann Powers YOU BETTER THINK: Why Feminist Cultural Criticism Still Matters in a "Post-Feminist," Peer-to-Peer World Tenth Annual USC Women in Higher Education Luncheon Sponsored by the Gender Studies Program and Center for Feminist Research at USC University of Southern California March 10, 2009 2 THE NORMAN LEAR CENTER Ann Powers: YOU BETTER THINK YOU BETTER THINK: Why Feminist Cultural Criticism Still Matters in a "Post-Feminist," Peer-to-Peer World Gender Studies Program . The Norman Lear Center Gender Studies at USC is an interdisciplinary program composed Founded in January 2000, the Norman Center for Feminist Research of faculty, students, and associated Lear Center is a multidisciplinary scholars who work together to research and public policy center For 20 years, CFR has worked, examine the world through the lens exploring implications of the together with the USC Gender Studies of gender. We cross cultures, regions, convergence of entertainment, Program, to provide the University of periods, academic disciplines, and commerce and society. On campus, Southern California's feminist theories in order to study: from its base in the USC Annenberg community with research the meaning of "male" and "female" School for Communication, the Lear opportunities for the study of women, as well as the actions of women and Center builds bridges between schools gender, and feminis. A variety of men. and disciplines whose faculty study seminars, workshops, conferences, social roles and sexual identities in aspects of entertainment, media and and informal gatherings have brought the contexts of race, class, and culture. Beyond campus, it bridges the together a network of faculty, ethnicity. -

5 Letter from the Editors

BURNmagazine Issue 5 Letter from the Editors What is Burn? As new editors resurrecting Burn Magazine from its last publication in 2010, we look to embody our preceding editors’ hopes for Burn, despite moving into the future; that is, compiling a literary magazine that allows its readers to momentarily escape their busy collegiate lives in Boston and immerse themselves in the words, thoughts, and images of their undergraduate colleagues. We chose the following pieces based on both on their unique concepts and varying styles, though we decided against a specific theme for this issue to bind the contributions together aside from the fact that they all were written by undergraduates. Our hope is that because of the wide range of pieces we chose, Burn will appeal to all types of people at Boston University as a way to experience the creativity of those who may be outside of their discipline’s realm—we want this magazine and its contributors’ voices to reach people outside of just family and friends (though we do appreciate these you). We hope you enjoy the pieces we selected from our submissions this semester, and we look forward to the future of Burn Magazine. Best, Jenna Bessemer and Tori Sommerman, Co-Editors Zachary Bos, Advising Editor Founded in 2006 by Catherine Craft, Mary Sullivan, and Chase Quinn. Boston University undergraduates may send submissions to [email protected]. Manuscripts are considered year-round. Burn Magazine is published according to an irregular schedule by the Boston University Literary Society; printed by the Pen & Anvil Press. Front cover photograph by Tori Sommerman, COM 2013. -

Perfect Partner

PERFECT PARTNER A film by Kim Gordon, Tony Oursler and Phil Morrison starring Michael Pitt and Jamie Bochert, with a live soundtrack performed by Kim Gordon, Jim O’Rourke, Ikue Mori, Tim Barnes and DJ Olive As a significant figure of alternative/avant-garde rock and one of the founders of Sonic Youth, Kim Gordon is a truly creative spirit. Enigmatic, iconic, original and multi- faceted, she is increasingly working in the medium of visual arts and diversifying her music projects into more experimental territory. Perfect Partner is a first time collaboration between Kim Gordon, highly renowned artist Tony Oursler and acclaimed filmmaker Phil Morrison. In a response to America’s enchantment with car culture, this surreal psychodrama-cum-road movie starring Michael Pitt (The Dreamers, Hedwig And the Angry Inch, Bully and Gus Van Sant’s upcoming Last Days) and Jamie Bochert unfolds to a thundering free rock live soundtrack. The sound world of Perfect Partner is textural improvised music breaking into occasional songs that interact with the narrative of the film. Kim Gordon is joined on stage by fellow Sonic Youth collaborator, producer extraordinaire, composer and School Of Rock collaborator Jim O’Rourke, percussionist Tim Barnes, laptop virtuoso Ikue Mori and turntablist DJ Olive. Audiences across the UK should fasten their seatbelts for an invigorating trip through live music, video and projection in this one-off cross media adventure. Gordon and Oursler’s shared fascination with the dream lifestyle promised by car manufacturers, and the aspirational language of car advert copy (selling cars as our ‘perfect partner’), provided the inspiration for this hugely inventive project. -

Women Singer-Songwriters As Exemplary Actors: the Music of Rape and Domestic Violence

Women Singer-Songwriters as Exemplary Actors: The Music of Rape and Domestic Violence KATHANNE W. GREENE At the 2016 Oscars, Lady Gaga, joined onstage by fifty rape survivors, performed the song “Til It Happens to You.” The Oscar-nominated song by Lady Gaga and Diane Warren was written for The Hunting Ground, a documentary film about campus sexual assault. Over thirty-one million people viewed the Oscar performance, which brought some in the audience to tears, and the video on Vevo has received over twenty-nine million views with another twenty-eight million views on YouTube. The film, video, and performance are the result of a growing political and social movement by young high school and college women to force schools, universities, and colleges to vigorously respond to rape and sexual harassment on campus. In response to complaints filed by more and more young women, the Obama Administration and the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) in the Department Education began investigating claims that schools, colleges, and universities were not actively and adequately responding to claims of sexual assault and harassment despite passage of the Clery Act of 1990. The Clery Act requires colleges and universities to report data on crime on campus, provide support and accommodations to survivors, and establish written policies and procedures for the handling of campus crime.1 Since 2011, the OCR has expanded its efforts to address sexual assault on campuses as violations of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 that prohibits sex discrimination