Fire As a Selective Agent for Both Serotiny and Nonserotiny Over Space and Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Plants Used by Carnaby's Black Cockatoo

Plants Used by Carnaby's Black Cockatoo List prepared by Christine Groom, Department of Environment and Conservation 15 April 2011 For more information on plant selection or references used to produce this list please visit the Plants for Carnaby's Search Tool webpage at www.dec.wa.gov.au/plantsforcarnabys Used for Soil type Soil drainage Priority for planting Sun Species Growth form Flower colour Origin for exposure Carnaby's Feeding Nesting Roosting Clayey Gravelly Loamy Sandy drained Well drained Poorly Waterlogged affected Salt Acacia baileyana (Cootamundra wattle)* Low Tree Yellow Australian native Acacia pentadenia (Karri Wattle) Low Tree Cream WA native Acacia saligna (Orange Wattle) Low Tree Yellow WA native Agonis flexuosa (Peppermint Tree) Low Tree White WA native Araucaria heterophylla (Norfolk Island Pine) Low Tree Green Exotic to Australia Banksia ashbyi (Ashby's Banksia) Medium Tree or Tall shrub Yellow, Orange WA native Banksia attenuata (Slender Banksia) High Tree Yellow WA native Banksia baxteri (Baxter's Banksia) Medium Tall shrub Yellow WA native Banksia carlinoides (Pink Dryandra) Medium Medium or small shrub White, cream, pink WA native Banksia coccinea (Scarlet Banksia) Medium Tree Red WA native Banksia dallanneyi (Couch Honeypot Dryandra) Low Medium or small shrub Orange, brown WA native Banksia ericifolia (Heath-leaved Banksia) Medium Tall shrub Orange Australian native Banksia fraseri (Dryandra) Medium Medium or small shrub Orange WA native Banksia gardneri (Prostrate Banksia) Low Medium -

Method to Estimate Dry-Kiln Schedules and Species Groupings: Tropical and Temperate Hardwoods

United States Department of Agriculture Method to Estimate Forest Service Forest Dry-Kiln Schedules Products Laboratory Research and Species Groupings Paper FPL–RP–548 Tropical and Temperate Hardwoods William T. Simpson Abstract Contents Dry-kiln schedules have been developed for many wood Page species. However, one problem is that many, especially tropical species, have no recommended schedule. Another Introduction................................................................1 problem in drying tropical species is the lack of a way to Estimation of Kiln Schedules.........................................1 group them when it is impractical to fill a kiln with a single Background .............................................................1 species. This report investigates the possibility of estimating kiln schedules and grouping species for drying using basic Related Research...................................................1 specific gravity as the primary variable for prediction and grouping. In this study, kiln schedules were estimated by Current Kiln Schedules ..........................................1 establishing least squares relationships between schedule Method of Schedule Estimation...................................2 parameters and basic specific gravity. These relationships were then applied to estimate schedules for 3,237 species Estimation of Initial Conditions ..............................2 from Africa, Asia and Oceana, and Latin America. Nine drying groups were established, based on intervals of specific Estimation -

Irrigation of Amenity Horticulture with Recycled

Acknowledgements The Smart Water Fund encourages innovation in water recycling, water conservation and biosolid management to help secure Victoria’s water supplies now and in the future. Smart Water Fund The delivery of these research and development outcomes, from the Australian Coordinator for Recycled Water use in Horticulture project, to the horticultural industry is made possible by the Commonwealth Government’s 50% investment in all Horticulture Australia’s research and development initiatives supported by Horticulture Australia Limited. Publisher s Arris Pty Ltd, Melbourne, 646a Bridge Road, Richmond, Victoria 3121. rri www.arris.com.au ISBN: 0 9750134 9 1 a Reviewers Wayne Kratisis, Melton Council. Dr Anne-Maree Boland, RMCG, Camberwell. Peter Symes, Royal Botanical Gardens, Melbourne. Guy Hoffensetz, Netafim Australia. Alison Anderson, Arris Pty Ltd, Sydney. Disclaimer The information contained in this publication is intended for general use, to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the sustainable management of land, water and vegetation. It includes general statements based on scientific research. Readers are advised and need to be aware that this information may be incomplete or unsuitable for use in specific situations. Before taking any action or decision based on the information in this publication, readers should seek expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, Arris Pty Ltd (including its employees and consultants), the authors, and the Smart Water Fund and its partners do not assume liability of any kind whatsoever resulting from any person’s use or reliance upon the content of this publication. Copyright © 2008: Copyright of this publication, and all information it contains is invested in Arris Pty Ltd and the Authors. -

Extinction, Transoceanic Dispersal, Adaptation and Rediversification

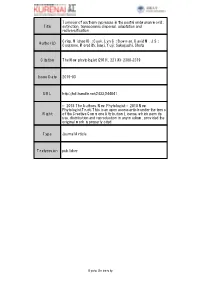

Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: Title extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Crisp, Michael D.; Cook, Lyn G.; Bowman, David M. J. S.; Author(s) Cosgrove, Meredith; Isagi, Yuji; Sakaguchi, Shota Citation The New phytologist (2019), 221(4): 2308-2319 Issue Date 2019-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/244041 © 2018 The Authors. New Phytologist © 2018 New Phytologist Trust; This is an open access article under the terms Right of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Research Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Michael D. Crisp1 , Lyn G. Cook2 , David M. J. S. Bowman3 , Meredith Cosgrove1, Yuji Isagi4 and Shota Sakaguchi5 1Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, RN Robertson Building, 46 Sullivans Creek Road, Acton (Canberra), ACT 2601, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072, Australia; 3School of Natural Sciences, The University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart, Tas 7001, Australia; 4Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan; 5Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan Summary Author for correspondence: Cupressaceae subfamily Callitroideae has been an important exemplar for vicariance bio- Michael D. Crisp geography, but its history is more than just disjunctions resulting from continental drift. We Tel: +61 2 6125 2882 combine fossil and molecular data to better assess its extinction and, sometimes, rediversifica- Email: [email protected] tion after past global change. -

Proteaceae), with a Key to the Species of Phaeophleospora

Fungal Diversity Phaeophleospora faureae comb. novo associated with leaf spots on Faurea saligna (Proteaceae), with a key to the species of Phaeophleospora Joanne E. Taylor* and Pedro W. Crous Department of Plant Pathology, University of Stellenbosch, Private Bag Xl, Stellenbosch 7602, South Africa; * e-mail: [email protected] Taylor, J.E. and erous, P.W. (1999). Phaeophleosporafaureae comb. novo associated with leaf spots on Faurea saligna (Proteaceae), with a key to the species of Phaeophleospora. Fungal Diversity 3: 153-158. During studies of the fungal pathogens occurring on Proteaceae in South Africa, the type specimen of Stilbospora faureae was examined. This fungus was found to be a species of Phaeophleospora, and is transferred to this genus in the present paper. A key to the species in Phaeophleospora is also given. Key words: pathogen, Phaeophleospora, Proteaceae, Stilbospora Introduction Phaeophleospora was considered to be a nomen dubium (Sutton, 1977), until Crous et al. (1997) resurrected it as an earlier name for the coelomycete genus Kirramyces 1. Walker, B. Sutton and 1. Pascoe. There are currently 11 species in Phaeophleospora (Walker et al., 1992; Sutton, 1993; Palm, 1996; Wingfield et al., 1996; Wu et al., 1996; Crous et al., 1997; Crous, 1998; Crous and Palm, 1999) and three of these occur on Proteaceae hosts. Phaeophleospora is associated with leaf spots and is characterised by sub• epidermal, dark-walled pycnidia, which become open and cup-shaped at maturity (Crous et al., 1997). Under conditions of high humidity, these conidiomata exude masses of conidia in a long, brown to black cirrus (Crous et al., 1997). -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Inventory of Taxa for the Fitzgerald River National Park

Flora Survey of the Coastal Catchments and Ranges of the Fitzgerald River National Park 2013 Damien Rathbone Department of Environment and Conservation, South Coast Region, 120 Albany Hwy, Albany, 6330. USE OF THIS REPORT Information used in this report may be copied or reproduced for study, research or educational purposed, subject to inclusion of acknowledgement of the source. DISCLAIMER The author has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information used. However, the author and participating bodies take no responsibiliy for how this informrion is used subsequently by other and accepts no liability for a third parties use or reliance upon this report. CITATION Rathbone, DA. (2013) Flora Survey of the Coastal Catchments and Ranges of the Fitzgerald River National Park. Unpublished report. Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank many people that provided valable assistance and input into the project. Sarah Barrett, Anita Barnett, Karen Rusten, Deon Utber, Sarah Comer, Charlotte Mueller, Jason Peters, Roger Cunningham, Chris Rathbone, Carol Ebbett and Janet Newell provided assisstance with fieldwork. Carol Wilkins, Rachel Meissner, Juliet Wege, Barbara Rye, Mike Hislop, Cate Tauss, Rob Davis, Greg Keighery, Nathan McQuoid and Marco Rossetto assissted with plant identification. Coralie Hortin, Karin Baker and many other members of the Albany Wildflower society helped with vouchering of plant specimens. 2 Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. -

7008 Australian Native Plants Society Australia Hakea

FEBRUARY 20 10 ISSN0727 - 7008 AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS SOCIETY AUSTRALIA HAKEA STUDY GROUP NEWSLETTER NUMBER 42 Leader: Paul Kennedy PO Box 220 Strathmerton,Vic. 3 64 1 e mail: hakeaholic@,mpt.net.au Dear members. The last week of February is drawing to a close here at Strathrnerton and for once the summer season has been wetter and not so hot. We have had one very hot spell where the temperature reached the low forties in January but otherwise the maximum daily temperature has been around 35 degrees C. The good news is that we had 25mm of rain on new years day and a further 60mm early in February which has transformed the dry native grasses into a sea of green. The native plants have responded to the moisture by shedding that appearance of drooping lack lustre leaves to one of bright shiny leaves and even new growth in some cases. Many inland parts of Queensland and NSW have received flooding rains and hopefully this is the signal that the long drought is finally coming to an end. To see the Darling River in flood and the billabongs full of water will enable regeneration of plants, and enable birds and fish to multiply. Unfortunately the upper reaches of the Murray and Murrurnbidgee river systems have missed out on these flooding rains. Cliff Wallis from Merimbula has sent me an updated report on the progress of his Hakea collection and was complaining about the dry conditions. Recently they had about 250mm over a couple of days, so I hope the species from dryer areas are not sitting in waterlogged soil. -

Rates of Molecular Evolution and Diversification in Plants: Chloroplast

Duchene and Bromham BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:65 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/65 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Rates of molecular evolution and diversification in plants: chloroplast substitution rates correlate with species-richness in the Proteaceae David Duchene* and Lindell Bromham Abstract Background: Many factors have been identified as correlates of the rate of molecular evolution, such as body size and generation length. Analysis of many molecular phylogenies has also revealed correlations between substitution rates and clade size, suggesting a link between rates of molecular evolution and the process of diversification. However, it is not known whether this relationship applies to all lineages and all sequences. Here, in order to investigate how widespread this phenomenon is, we investigate patterns of substitution in chloroplast genomes of the diverse angiosperm family Proteaceae. We used DNA sequences from six chloroplast genes (6278bp alignment with 62 taxa) to test for a correlation between diversification and the rate of substitutions. Results: Using phylogenetically-independent sister pairs, we show that species-rich lineages of Proteaceae tend to have significantly higher chloroplast substitution rates, for both synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions. Conclusions: We show that the rate of molecular evolution in chloroplast genomes is correlated with net diversification rates in this large plant family. We discuss the possible causes of this relationship, including molecular evolution driving diversification, speciation increasing the rate of substitutions, or a third factor causing an indirect link between molecular and diversification rates. The link between the synonymous substitution rate and clade size is consistent with a role for the mutation rate of chloroplasts driving the speed of reproductive isolation. -

Evolutionary History of Floral Key Innovations in Angiosperms Elisabeth Reyes

Evolutionary history of floral key innovations in angiosperms Elisabeth Reyes To cite this version: Elisabeth Reyes. Evolutionary history of floral key innovations in angiosperms. Botanics. Université Paris Saclay (COmUE), 2016. English. NNT : 2016SACLS489. tel-01443353 HAL Id: tel-01443353 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01443353 Submitted on 23 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. NNT : 2016SACLS489 THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE PARIS-SACLAY, préparée à l’Université Paris-Sud ÉCOLE DOCTORALE N° 567 Sciences du Végétal : du Gène à l’Ecosystème Spécialité de Doctorat : Biologie Par Mme Elisabeth Reyes Evolutionary history of floral key innovations in angiosperms Thèse présentée et soutenue à Orsay, le 13 décembre 2016 : Composition du Jury : M. Ronse de Craene, Louis Directeur de recherche aux Jardins Rapporteur Botaniques Royaux d’Édimbourg M. Forest, Félix Directeur de recherche aux Jardins Rapporteur Botaniques Royaux de Kew Mme. Damerval, Catherine Directrice de recherche au Moulon Président du jury M. Lowry, Porter Curateur en chef aux Jardins Examinateur Botaniques du Missouri M. Haevermans, Thomas Maître de conférences au MNHN Examinateur Mme. Nadot, Sophie Professeur à l’Université Paris-Sud Directeur de thèse M. -

Bindaring Park Bassendean - Fauna Assessment

Bindaring Park Bassendean - Fauna Assessment Wetland habitat within Bindaring Park study area (Rob Browne-Cooper) Prepared for: Coterra Environment Level 3, 25 Prowse Street, WEST PERTH, WA 6005 Prepared by: Robert Browne-Cooper and Mike Bamford M.J. & A.R. Bamford Consulting Ecologists 23 Plover Way KINGSLEY WA 6026 6th April 2017 Bindaring Park - Fauna Assessment Summary Bamford Consulting Ecologists was commissioned by Coterra Environment to conduct a Level 1 fauna assessment (desktop review and site inspection) of Bindaring Park in Bassendean (the study area). The fauna survey is required to provide information on the ecological values for the Town of Bassendean’s Stage 2 Bindaring Wetland Concept Plan Development. This plan include developing design options (within wetland area) to enhance ecological values and habitat. The purpose of this report is to provide information on the fauna values of the habitat, particularly for significant species, and an overview of the ecological function of the site within the local and regional context. This assessment focuses on vertebrate fauna associated with the wetland and surrounding parkland vegetation within the study area, with consideration for connectivity with the Swan River. An emphasis is placed on locally-occurring conservation significant species and their habitat. Relevant species include Carnaby’s Black-Cockatoo, Forest Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo, and other local native species such as the Water Rat or Rakali. The fauna investigations were based on a desktop assessment and a field survey conducted in February 2017. The desktop study identified 180 vertebrate fauna species as potentially occurring in the Bindaring Park study area (see Table 3 and Appendix 5): five fish, 6 frogs, 20 reptiles, 134 birds, 8 native and 7 introduced mammals. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Mao et al. 10.1073/pnas.1114319109 SI Text BEAST Analyses. In addition to a BEAST analysis that used uniform Selection of Fossil Taxa and Their Phylogenetic Positions. The in- prior distributions for all calibrations (run 1; 144-taxon dataset, tegration of fossil calibrations is the most critical step in molecular calibrations as in Table S4), we performed eight additional dating (1, 2). We only used the fossil taxa with ovulate cones that analyses to explore factors affecting estimates of divergence could be assigned unambiguously to the extant groups (Table S4). time (Fig. S3). The exact phylogenetic position of fossils used to calibrate the First, to test the effect of calibration point P, which is close to molecular clocks was determined using the total-evidence analy- the root node and is the only functional hard maximum constraint ses (following refs. 3−5). Cordaixylon iowensis was not included in in BEAST runs using uniform priors, we carried out three runs the analyses because its assignment to the crown Acrogymno- with calibrations A through O (Table S4), and calibration P set to spermae already is supported by previous cladistic analyses (also [306.2, 351.7] (run 2), [306.2, 336.5] (run 3), and [306.2, 321.4] using the total-evidence approach) (6). Two data matrices were (run 4). The age estimates obtained in runs 2, 3, and 4 largely compiled. Matrix A comprised Ginkgo biloba, 12 living repre- overlapped with those from run 1 (Fig. S3). Second, we carried out two runs with different subsets of sentatives from each conifer family, and three fossils taxa related fi to Pinaceae and Araucariaceae (16 taxa in total; Fig.