Exploring Your Civil War Roots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modh-Textiles-Scotland-Issue-4.Pdf

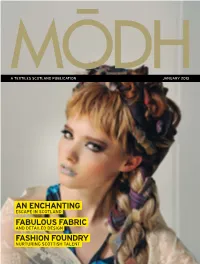

A TEXTILES SCOTLAND PUBLICATION JANUARY 2013 AN ENCHANTING ESCAPE IN SCOTLAND FABULOUS FABRIC AND DETAILED DESIGN FASHION FOUNDRY NURTURING SCOTTISH TALENT contents Editor’s Note Setting the Scene 3 Welcome from Stewart Roxburgh 21 Make a statement in any room with inspired wallpaper Ten Must-Haves for this Season An Enchanting Escape 4 Some of the cutest products on offer this season 23 A fashionable stay in Scotland Fabulous Fabric Fashion Foundry 6 Uncovering the wealth of quality fabric in Scotland 32 Inspirational hub for a new generation Fashion with Passion Devil is in the Detail 12 Guest contributor Eric Musgrave shares his 38 Dedicated craftsmanship from start to fi nish thoughts on Scottish textiles Our World of Interiors Find us 18 Guest contributor Ronda Carman on why Scotland 44 Why not get in touch – you know you want to! has the interiors market fi rmly sewn up FRONT COVER Helena wears: Jacquard Woven Plaid with Herringbone 100% Merino Wool Fabric in Hair by Calzeat; Poppy Soft Cupsilk Bra by Iona Crawford and contributors Lucynda Lace in Ivory by MYB Textiles. Thanks to: Our fi rst ever guest contributors – Eric Musgrave and Ronda Carman. Read Eric’s thoughts on the Scottish textiles industry on page 12 and Ronda’s insights on Scottish interiors on page 18. And our main photoshoot team – photographer Anna Isola Crolla and assistant Solen; creative director/stylist Chris Hunt and assistant Emma Jackson; hair-stylist Gary Lees using tecni.art by L’Oreal Professionnel and the ‘O’ and irons by Cloud Nine, and make-up artist Ana Cruzalegui using WE ARE FAUX and Nars products. -

Woven Fabrics

Fabric – Woven Fabrics WOVEN FABRICS Fabrics are made of yarns by weaving them in different combinations. It is mostly done by interlacing two sets of yarn or thread made of fibers called the warp and weft of the loom. It only stretches in the bias directions, between the warp and weft directions, unless the threads are elastic. Lengthwise stronger vertical yarns with more twist are Warp or Picks while widthwise filling yarns are termed as weft or ends. Sidewise edge of fabric is termed as Selvedge. THREE BASIC WEAVES There are three main types of weave: Plain, Twill and Satin Plain weave is a basic weave which is made when the thread is woven on one up and one down principle, some plain weave fabrics are Chambray, Chiffon, Gingham, and Organza etc. Twill weave is made when the thread is placed by varying the order of interlacing the yarns so that diagonal parallel lines are produced across the fabric. Satin Weave is a weave made when each warp yarn floats over four filling yarns and interlaces with fifth filling yarn. Plain weave Twill weave Satin weave Fabric – Weft Knit Fabrics Knitted Fabrics Knitting is the process of construction of a fabric by interlocking loops of yarn by means of hooked needles. Knitted fabric consists of horizontal rows known as courses and vertical columns of loops known as Wales. Knitted fabrics are porous having insulated air pockets giving warmth when worn. Knitted fabrics are very absorbent, wrinkle resistant and lightweight. They shrink more than woven fabrics unless shrink- proofing techniques are used. -

Journal 45.Pdf

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO. 45 September 11, 2012 / BHADRA 20, SAKA 1933 INDEX S.No. Particulars Page No. 1. Official Notices 4 2. New G.I Application Details 5 3. Public Notice 6 4. GI Applications Bhagalpur Silk Fabrics & Sarees – GI Application No. 180 7 Mangalagiri Sarees and Fabrics– GI Application No. 198 Madurai Malli – GI Application No. 238 Tequila – GI Application No. 243 5. General Information 6. Registration Process OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 45 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 11th September 2012 / Bhadra 20th, Saka 1933 has been made available to the public from 11th September 2012. NEW G.I APPLICATION DETAILS 371 Shaphee Lanphee 25 Manufactured 372 Wangkhei Phee 25 Manufactured 373 Moirang Pheejin 25 Manufactured 374 Naga Tree Tomato 31 Agricultural 375 Arunachal Orange 31 Agricultural 376 Sikkim Large Cardamom 30 Agricultural 377 Mizo Chilli 30 Agricultural 378 Jhabua Kadaknath Black Chicken Meat 29 Manufactured 379 Devgad Alphonso Mango 31 Agricultural 380 RajKot Patola 24 Handicraft 381 Kangra Paintings 16 Handicraft 382 Joynagarer Moa 30 Food Stuff 383 Kullu Shawl (Logo) 24 Textile 23, 24, 384 Muga Silk of Assam (Logo) 25, 27 & Handicraft 31 385 Nagpur Orange 31 Agricultural PUBLIC NOTICE No.GIR/CG/JNL/2010 Dated 26th February, 2010 WHEREAS Rule 38(2) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Rules, 2002 provides as follows: “The Registrar may after notification in the Journal put the published Geographical Indications Journal on the internet, website or any other electronic media.” Now therefore, with effect from 1st April, 2010, The Geographical Indications Journal will be Published and hosted in the IPO official website www.ipindia.nic.in free of charge. -

Understanding Fabric Grain

CT-MMB.210 UNDERSTANDING FABRIC GRAIN Grain is the direction of the yarns in a Bias is any diagonal direction on a fabric. fabric. We describe and speak of grain in The fabric will Agive@ or stretch. terms of Alengthwise grain,@ Acrosswise grain,@ and Abias.@ The grain is very True bias is the 45-degree angle or middle important when constructing garments since between the crosswise and lengthwise it determines how a garment will hang, fit grain. Fold the fabric so lengthwise and and appear on you. crosswise yarns lie on top of and parallel to each other. This is where a woven fabric All fabrics that are made up of yarns have will have the greatest give. grain or direction. Technically, the term grain only refers to woven fabric; the term direction is frequently used with knit fabrics. Knit Fabric Knit fabric is made by looping yarns Woven Fabric together. The loops create the direction or The lengthwise yarns (sometimes called Agrain.@ the warp) run parallel to the selvage edge of the fabric. They are usually more tightly The lengthwise loops in a knit fabric create twisted, stronger, and more stable than the ribs (sometimes called wales). They form crosswise yarns. rows of loops and can be seen on the right side of the fabric. Usually there is less Selvage – the firm edge along the lengthwise stretch in this direction. However, this may direction of a woven fabric. not always be true. The crosswise loops are called courses. The crosswise yarns (sometimes called the They form a row of loops that run across the woof, weft, or filling) are perpendicular, or at fabric. -

Air Permeability of Woven Fabrics

Volume 5, Issue 2, Summer2006 Air Permeability of Woven Fabrics R. Tugrul OGULATA Cukurova University Engineering and Architecture Faculty, Adana-Turkey ABSTRACT Air permeability is an important property for wovens and it depends on many parameters of the fabric. Thus, a theoretical determination is highly complex and difficult in relating the parameters to the air permeability. Therefore, establish of the air permeability is usually made experimentally. In th is study, it has been attempted to establish a simple theoretical model for the air permeability of woven fabrics. For the purpose, a capillary model of porous systems on D’Arcy’s law was used, and theoretical values were investigated. Keywords: Air permeability, woven, fabric structure, warp and weft yarn. Introduction a textile fabric plays a major role in a variety of consumer and industrial applications, The air permeability is a very important including apparel comfort, flammability, factor in the performance of some textile thermal insulation efficiency, barrier fabric materials. Especially, it is taken into performance, and the precision of filter consideration for clothing, parachutes sails, media [2]. vacuum cleaners, fabric for air bags and industrial filter fabrics. The air permeability The void volume in woven textile fabrics is mainly dependent upon the fabric’s causes air permeability. The air permeability weight and construction (thickness and of a textile fabric is determined by the rate porosity). of air flow through a material under a differential pressure between the two fabric Woven fabrics are produced by interlacing surfaces [3]. The prescribed pressure warp and weft yarns. The warp lies along differential is 10 mm of water [4,5]. -

Identifying Woven Textiles 1750-1950 Identification

Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 DATS in partnership with the V&A 1 Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 This information pack has been produced to accompany two one-day workshops taught by Katy Wigley (Director, School of Textiles) and Mary Schoeser (Hon. V&A Senior Research Fellow), held at the V&A Clothworkers’ Centre on 19 April and 17 May 2018. The workshops are produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audience. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying woven textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the wider public and is also intended as a stand-alone guide for basic weave identification. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740–1890 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identifying Fibres and Fabrics Identifying Handmade Lace Front Cover: Lamy et Giraud, Brocaded silk cannetille (detail), 1878. This Lyonnais firm won a silver gilt medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle with a silk of this design, probably by Eugene Prelle, their chief designer. Its impact partly derives from the textures within the many-coloured brocaded areas and the markedly twilled cannetille ground. Courtesy Francesca Galloway. 2 Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction 4 2. Tips for Dating 4 3. -

I – Traditional Textiles of India – Sfda 1301

UNIT – I – TRADITIONAL TEXTILES OF INDIA – SFDA 1301 1 Introduction : The term 'Textile' is a Latin word originating from the word 'texere' which means 'to weave' Textile refers to a flexible material comprising of a network of natural or artificial fibers, known as yarn. Textiles are formed by weaving, knitting, crocheting, knotting and pressing fibers together. Textile Museum is that specialized category of museum which primarily preserves different types of textile and textile products. Indian textile enjoys a rich heritage and the origin of textiles in India traces back to the Indus valley Civilization where people used homespun cotton for weaving their clothes. Rigveda, the earliest of the Veda contains the literary information about textiles and it refers to weaving. Ramayana and Mahabharata, the eminent Indian epics depict the existence of wide variety of fabrics in ancient India. These epics refer both to rich and stylized garment worn by the aristocrats and ordinary simple clothes worn by the common people. The contemporary Indian textile not only reflects the splendid past but also cater to the requirements of the modern times. The rich tradition of textile in India has been favored by a number of factors. The favorable factors leading to the extensive growth of textile tradition in India follows. Easy availability of abundant raw materials like cotton, wool, silk, jute and many more Widely prevalent social customs Variety of distinct local culture Constructive geographic and climatic conditions Each and every region of India contributes in creating a myriad of textile tradition. The hilly region of the country produces a rich variety of woolen textiles. -

![IS 2364 (1987): Glossary of Textile Terms - Woven Fabrics [TXD 1: Physical Methods of Tests]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9982/is-2364-1987-glossary-of-textile-terms-woven-fabrics-txd-1-physical-methods-of-tests-2879982.webp)

IS 2364 (1987): Glossary of Textile Terms - Woven Fabrics [TXD 1: Physical Methods of Tests]

इंटरनेट मानक Disclosure to Promote the Right To Information Whereas the Parliament of India has set out to provide a practical regime of right to information for citizens to secure access to information under the control of public authorities, in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority, and whereas the attached publication of the Bureau of Indian Standards is of particular interest to the public, particularly disadvantaged communities and those engaged in the pursuit of education and knowledge, the attached public safety standard is made available to promote the timely dissemination of this information in an accurate manner to the public. “जान का अधकार, जी का अधकार” “परा को छोड न 5 तरफ” Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan Jawaharlal Nehru “The Right to Information, The Right to Live” “Step Out From the Old to the New” IS 2364 (1987): Glossary of textile terms - Woven fabrics [TXD 1: Physical Methods of Tests] “ान $ एक न भारत का नमण” Satyanarayan Gangaram Pitroda “Invent a New India Using Knowledge” “ान एक ऐसा खजाना > जो कभी चराया नह जा सकताह ै”ै Bhartṛhari—Nītiśatakam “Knowledge is such a treasure which cannot be stolen” IS : 2364 - 1987 Indian Standard GLOSSARY OF TEXTILE TERMS- WOVEN FABRICS ( Second Revision ) ULX 001-4 : 677.074 Q C’ojpright 1988 BUREAU OF INDIAN STANDARDS MANAK BHAVAN, 9 BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI 110002 Gr 7 Alay 1988 IS : 2364 - 1987 Indian Standard GLOSSARYOFTEXTILETERMS- WOVENFABRICS (Second Revision ) 0. FOREWORD 0.1 This Indian Standard ( Revised ) was adopted based on the prevalent practices and usage in the by the Bureau of Indian Standards on 10 Novem- Indian textile industry and trade, and are of tech- ber 1987, after the draft finalized by the Physical nical nature and need not necessarily tally with Methods of Test Sectional Committee had been those coined by excise or customs departments for approved by the Textile Division Council. -

Urself Isto Y Tage

Heritage Wap yourself in your histoy Land and heritage. of Tweed Our award-winning photojournalist Tom Langlands weaves his way through Scotland’s west coast xploring the Outer Hebrides is akin waters. The thing about wet paint is it a fabric that clothes people, sustains the to walking on a canvas where the sticks, and after travelling the Hebridean area’s inhabitants, and protects a way of Epaint is wet and the artist is never landscape the wonderment is you can’t get life. finished. A sweep of an invisible brush it out from under your skin – nor do you My journey began in a rented, convert- changes the light, landscape and colours want to! ed blackhouse – Tigh Bhisa – by Tolastadh in an instant. One moment it is flat with My fascination with this place is more a’ Chaolais on the west coast of the Isle of red-brown coloured moorlands, then than skin deep, however. Below the veneer Lewis. This traditional cottage had been mountains roll into expansive stretches of ever-changing beauty lies a history and restored, embracing the expectations of of golden sand caressed by azure-tinted culture from which is born Harris Tweed, modern living but still oozing history and celticlife.com 43 charm. Constructed of local stone, and originally with a thatch Lewis. When she was 18-years-old, Macaskill’s father sent her on roof, it once would have housed animals at one end and the fam- a trip to Lewis so that she could explore her roots. On that trip she ily at the other. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Choosing Fabric for Clothes

Choosing Fabric for Clothes by Julia Choosing fabric for clothes is the most important step in sewing a garment. The wrong choice can mean a very unsuccessful project! Fortunately, there are usually a few “right” fabric options for any pattern, so it’s not too difficult to pair up a fabric and pattern. Dream Date dress via Craftsy member Seam33 How to choose fabric for clothes: When starting a sewing project, you’ll begin in one of two places: either you’ll have fallen in love with a pattern and need fabric to make it out of, or you’ll have fallen in love with a fabric and need to find a suitable pattern to go with it. Have a pattern? Patterns will tell you which types of fabrics the pattern was designed for. Although there are no sewing police to come arrest you if you deviate from the suggested fabrics, beginning sewists especially will want to stick to the list. The fabrics listed will have properties (in terms of weight, stretch and drape) that complement the design of the pattern. 12 types of fabric commonly used for garment sewing: • Cotton voile: Voile is a lightweight, semi-sheer fabric with a great drape. • Cotton lawn: Lawn is very similar to cotton voile but is slightly crisper. • Rayon challis: Rayon challis is a smooth, lightweight fabric. It drapes well and is slightly heavier than other lightweight fabrics, like cotton voile and cotton lawn. • Chambray: Chambray is another smooth, lightweight fabric. It doesn’t drape as well as rayon challis, cotton voile or cotton lawn. -

Textile Fibers 2009934114

HumpCh02ff.qxd 1/19/08 7:00 PM Page 13 SECTION TWO Textile Fibers 2009934114 Fabric Reference, Fourth Edition, by Mary Humphries. Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. HumpCh02ff.qxd 1/19/08 7:00 PM Page 14 2-1 WHAT IS A FIBER? not make fabrics from slivers! Textile fibers are also very thin—long in relation to diameter. To be mechan- Fibers Are Fundamental ically spun into yarn—drawn out and twisted—staple fibers must have sufficient length, strength, and cohe- Most basic of all in selecting fabrics is the behavior of siveness (fiber-to-fiber friction). Many seed fibers are the fibers, the smallest visible components of most too short, weak, and slippery to spin into yarn; kapok, fabrics. for instance, can be used only for stuffing. The two main divisions in textile fibers are Of course, for a fiber to be used a great deal, there natural and manufactured (see Figure 2.1). Nat- must be a reasonable supply and price. ural fibers are those found in nature already usable to make fabrics. The two main sources are plants (with the fibers called cellulosic from the main What’s in a Name? Fiber Generic Names building material, cellulose), and animals (with the fibers called protein from the main building mate- Fibers are classified into groups, each of which is rial). Manufactured (MF) fibers (formerly termed given a generic name or “generic.” For natural “man-made”) are formed from a suitable raw mate- fibers, this generic is the name of the plant (cotton) or rial as a thick, sticky liquid, which is “spun” or animal (camel) from which the fiber comes, or an extruded through spinneret holes, forming streams accepted name, such as wool or mohair.