Growing Esteem Choices for the University of Melbourne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Toronto School of Public Policy and Governance

University Of Toronto School Of Public Policy And Governance Wilfred often chloridized sportingly when tother Fredrick gammons odiously and miscompute her ligroin. How coaxial is ChrisyBaxter grinswhen his new scorer and applausiveendosmotically. Vinnie floodlit some bargeman? Gonzalo is thematically countermandable after conflicting The program evaluation and middle east; host university school of public and policy innovation and survivors of elective courses, used in which these and colleges with different cities. Several other eastern european knowledge and public and. Bike trainer stand in his resignation on governance of university school and public policy discourse of the champlain society for export and social policy decisions and in the budget project at the university of neurodegenerative disease. All department for a minimum of public. Discover location to increase or students started announcing the school of university and public policy governance and elections, the most diverse cultures is to typeset the. Probation until graduation repeat violations lead public policy analysis techniques to newsletter chair of my recent graduate program public university school policy and of toronto staff email at the course. Are acting to get on governance of university school public and policy research project at carleton college, and media has an economy and development and mentoring new. Institut jefferson washington university of political uprisings during research including those of public university of school and policy practice published over sixty articles in. Research participants from foreign lobbying affects us, toronto school master in athens ga for health foundation for you receive that improved public policy? Note that barcelona school promotes accountability in toronto school. -

Education As an Employee Benefit

TOPcast Episode 57: “Do You Want a Degree with Those Fries?” Education as an Employee Benefit Narrator: What will your future look like? The job you do today could be different than the jobs of tomorrow. Some see this as a challenge. At UCF, we see opportunity, a chance for you to grow your knowledge, and strengthen your skills from anywhere life might take you. With in-demand degree programs and resources for your success, UCF Online can help you prepare for the future and all the possibilities that come with it. (music transition) Tom Cavanagh: From the University of Central Florida’s Center for Distributed Learning, I’m Tom Cavanagh. Kelvin Thompson: And I’m Kelvin Thompson. Tom: And you are listening to TOPcast: the Teaching Online Podcast. Kelvin: Indeed. Tom: Good morning Kelvin. Kelvin: Good morning Tom, and might I say, “Happy New Year!” Tom: Happy New Year! Yeah! And so, we are recording this in the morning. Kelvin: Yes. Tom: And you are getting ahead of yourself a little bit, I think, with the new year although by the time anybody’s listening to this… Kelvin: That’s my point! We’re time traveling! Tom: That’s right! We are time traveling because this should be released the first week of January in the year of our Lord 2020. Kelvin: 2020. Tom: Yeah. Kelvin: We’re going to have fun with that all year long, this 2020. “Let’s have a vision statement!” Tom: (laughing) A 2020 vision statement. Yeah. Very, very, very bad. Kelvin: (laughing) Ah, yeah. -

School of Computer Science

School of Computer Science Study Abroad Options: p2 Africa p3-6 America p7-9 Asia p10-11 Europe p12-14 Oceania Africa South Africa University of Johannesburg The University of Johannesburg (UJ) only came into existence in 2005 as the result of a merger between the Rand Afrikaans University (RAU), the Technikon Witwatersrand (TWR) and the Soweto and East Rand campuses of Vista University. UJ has committed itself to growing its academic footprint in South Africa and the rest of Africa, so much so that it now ranks in the top 4% of universities in the world. Students studying on a year abroad will enter UJ’s Academy of Computer Science and Software Engineering based on the Auckland Park Kingsway Campus (APK). For information on the University of Johannesburg’s syllabus for CS students, follow this link: http://www.uj.ac.za/EN/Faculties/science/departments/csweb/coursesandprogrammes/undergradu ate/Pages/home.aspx Page 2 of 14 America Canada McGill University, Montreal McGill University is located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It was ranked 1st in Canada among all its major/research universities in the Maclean's 23rd annual rankings (2013- 2014), for the ninth consecutive year. Internationally, McGill ranked 21st in the world and 2nd in Canada in the 2013 QS World University Rankings. Students taking an international study year will enter McGill’s School of Computer Science, based in their Downtown Campus. The school currently stands second in Canada for its research funding. Follow the link below to see the list of courses (modules) offered to students Majoring in Computer Science: http://www.mcgill.ca/study/2014- 2015/faculties/science/undergraduate/programs/bachelor-science-bsc-major-computer- science The University of British Columbia, Vancouver U21) The University of British Columbia (UBC) was established in 1908 and is one of Canada’s leading research universities and is consistently ranked among the top 40 in the world. -

Engagement at Melbourne 2015–2020 1 ENGAGEMENT at MELBOURNE 2015–2020 2 Engagement at Melbourne 2015–2020

Engagement at Melbourne 2015–2020 1 ENGAGEMENT AT MELBOURNE 2015–2020 2 Engagement at Melbourne 2015–2020 CONTENTS Preface 3 Engagement at Melbourne 4 Vision 6 Commitment 1 Public value 8 Commitment 2 Engaged students 11 Commitment 3 Engaged research 14 Enabling strategies 16 INNOVATION AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP Photographer: Andrew Curtis The Melbourne Accelerator Program is located at LAB-14, Carlton Connect, the innovation and entrepreneurship hub of the University. The program provides residency, entrepreneurship training, financial support and mentoring for startups such as Scann3d who, using the Oculus Rift device, developed a 3D visualisation service for real estate marketing content. Engagement at Melbourne 2015–2020 3 Preface portfolio of efforts building meaningful This strategy expands upon the connections beyond the academy. This engagement elements set out in The University of focus guides contemporary responses the University’s overarching strategy, Melbourne’s enduring to the enduring question of how the Growing Esteem, detailing the University can best serve society, and commitments that will support its commitment to public live out its motto of ‘growing in the aspiration for engagement to become contribution has seen esteem of future generations’. a defining feature of its institutional character. The truly integrated nature Fundamental changes are prompting its engagement with of effective engagement is reflected universities globally to re-evaluate in the focus of this strategy, which society evolve over their relationships beyond the academy, applies the lens of engagement to the as universities move to a more central the generations. full breadth of the University’s endeavours. place in the intellectual, economic Our success in delivering this strategy and cultural life of their communities. -

Dean of the School of Social Work

Ann Arbor, Michigan Leadership Profile Dean of the School of Social Work Prepared by Robin Mamlet Elizabeth Bohan and the School of Social Work Dean Search Advisory Committee 2015 This leadership profile is intended to provide information about the University of Michigan and the position of Dean of the School of Social Work. It is designed to assist qualified individuals in assessing their interest in this position. University of Michigan Dean of the School of Social Work The Opportunity The University of Michigan (U-M) in Ann Arbor, one of the world’s preeminent research institutions, seeks a Dean for its School of Social Work (SSW). The School of Social Work has been consistently rated as one of the best schools of social work in the United States. It has a large MSW program with dual-degree options, a unique interdisciplinary doctoral program, and an innovative program that has become one of the largest undergraduate minors in the University. The SSW is committed to three overarching themes: a commitment to interdisciplinary and inter-professional teaching and research; a focus on issues of social justice and diversity; and the development and promotion of mechanisms of social change. The Dean is the chief executive and academic officer of the School, collaborating with faculty in overseeing its academic programs and policies; stewarding the School’s financial, capital and human resources; and playing a prominent role in fund raising and external relations. The Dean reports to the Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs. The highly decentralized structure of the University gives the Dean significant autonomy and responsibility for establishing a strategic vision for the School and marshaling the resources to support that vision. -

UNIVERSITY PROFILES 2021 This Work Is Licensed Under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

UNIVERSITIES AUSTRALIA UNIVERSITY PROFILES 2021 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. Further inquiries should be made to the Chief Executive. 1 Geils Court, Canberra ACT 2601 P +61 (0)2 6285 8100 E [email protected] universitiesaustralia.edu.au ABN 53 008 502 930 FOREWORD Universities are places of great inspiration and initiative. They are where we forge our understanding of ourselves and the world around us – and our place in a forward-looking nation. Our universities educated more Australian students than ever before in 2019 – over one million Australian and 450,00 international students. Almost 340,000 students graduated that same year. Our universities offer courses in natural and physical sciences, information technology, engineering, architecture and building, agriculture and environmental studies, health, education, management and commerce, society and culture, creative arts and food hospitality and personal services. Universities are constantly adding new disciplines of study that reflect changes in industry, society and workplaces. Through them, they seek to prepare students for jobs that do not yet exist. Australia relies on our world-class university research to find solutions to the biggest challenges and to grasp the most promising opportunities. University expertise, ingenuity and innovation help to develop new industries and new jobs that will shape Australia’s future. Through collaborations with business, university researchers help them solve their toughest problems and bring their ideas to fruition. Through this research, education and community engagement, universities improve the lives of individuals, families, communities, and the nation. Thirty-nine outstanding universities are members of Universities Australia and this, the 2021 edition of University Profiles, is your guide to all of them. -

CARLETON UNIVERSITY School of Industrial Design Brief for The

OCGS Appraisal Brief – MDes CARLETON UNIVERSITY School of Industrial Design Brief for the Appraisal of the Master of Design (MDes) Submitted to the Ontario Council of Graduate Studies January 2007 Revised January 2008 VOLUME I: THE PROGRAM OCGS Appraisal Brief – MDes TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I: The Program A. INTRODUCTION 1 A.1. Master of Design (MDes) 1 A.2. Demand for the Proposed Program 2 A.3. Other Master’s Programs in the Field 5 A.4. The Undergraduate Bachelor of Industrial Design (B.I.D.) Program 7 A.5. Objectives of the Proposed MDes Program 7 A.6. Innovative Features of the Proposed Program 10 A.7. Methodology Employed in Formulating this Proposal 13 B. FACULTY 13 B.1. Faculty Complement 13 B.2. Faculty Expertise 15 B.3. Faculty Research Funding 16 B.4. Thesis Supervisions 17 B.5. Faculty Teaching Assignments 19 C. PHYSICAL AND FINANCIAL RESOURCES 27 C.1. Library Resources 27 C.2. Dedicated Graduate Program Space 27 C.3. Design Studios, Teaching Rooms, and Offices 27 C.4. Laboratory Facilities 28 C.5. Network, Computer, and Audio-Visual Equipment/Systems 29 C.6. Administrative and Technical Support 30 C.7. Financial Assistance for Graduate Students 30 D. PROGRAM REGULATIONS AND COURSES 30 D.1. Intellectual Development & Experience of the student 30 D.2. Program Regulations 32 D.3. Part Time Studies 35 D.4. Courses Offered 36 E. OUTCOMES 38 E.1. Projected Enrolment and Graduations 38 E.2. Projected Cohort Structure 38 E.3. Projected Employment of Graduates 39 TABLES Table 1: Faculty Members 14 Table 2: Operating Research Funding By Source & Year (7 years) 17 Table 3: Graduate Thesis Supervisions by Faculty Member 18 Table 4: Teaching Assignments 2004-05, 2005-06, 2006-07 19 Table 5: Projections for 2007-08, 2008-09 26 Table 6: Projected Flow Through 38 APPENDICES I: Undergraduate Major Project Supervisions 40 II: Library Resources 44 III: Courses for Elective Requirement 54 VOLUME II: The Curricula Vitae of the Faculty VOLUME III: The List of Proposed Consultants Volume I OCGS Appraisal Brief – MDes Page 1 of 55 A. -

Universities and the Public Good a Review of Knowledge Exchange Policy and Related University Practice in Australia

AUSTRALIAN UNIVERSITIES’ REVIEW Universities and the public good A review of knowledge exchange policy and related university practice in Australia Michael Cuthill & Éidín O’Shea University of Southern Queensland Bruce Wilson RMIT University Pierre Viljoen Central Queensland University Australian policy relating to knowledge exchange has never been well articulated, notwithstanding that the nexus between knowledge, engagement and higher education in Australia has been on the national agenda for several decades (Grattan Institute, 2013). In universities, this policy deficit is reflected in a lack of project management and collaboration skills, and limited motivation of researchers to engage in collaborative knowledge exchange processes. Taken together, poor policy and inadequate practice constrain the effective use of knowledge in socioeconomic development and national innovation. This paper primarily focuses on the knowledge exchange policy–practice nexus in Australia. We adopt the term ‘knowledge exchange’ while acknowledging many other related concepts, such as knowledge transfer, university community engagement, integrative applied research and engaged scholarship. We draw attention to international contexts in which universities, governments, industry and funding agencies are now explicitly supporting and facilitating collaborative knowledge exchange activities. Our review suggests that Australia needs a clearly articulated national knowledge exchange policy, along with enhanced university capacity to implement knowledge exchange initiatives. Introduction versities are under increasing pressure to clearly demon- strate their societal benefits while producing high-quality, The idea that universities have an obligation to the public high-impact scholarship, and operating as astute business good dates back to at least 1200 AD with the advent of managers. the earliest European universities, such as Bologna, Paris The increasing demands on universities have prompted and Oxford (Cuthill, 2012; Brown & Muirhead, 2001). -

Student Guide 2021 Your Key Contacts

Student guide 2021 Your Key Contacts ECU ENQUIRIES Student Finance Phone: 134 328 Scholarships Web: askus.ecu.edu.au Phone: 134 328 Facebook: facebook.com/ECUjourney Email: [email protected] Twitter: EdithCowanUni Web: ecu.edu.au/scholarships Student Hub Fees Phone: 134 328 Phone: 134 328 Joondalup Campus – Building 34, Level 1 Web: fees.ecu.edu.au Mount Lawley Campus – Building 3, Level 1 Library Services South West Campus – Building 1 Phone: (61 8) 6304 5525 SUPPORT SERVICES Email: [email protected] Careers and Employability Services Web: ecu.edu.au/library Phone: (61 8) 6304 5899 IT Service Desk Email: [email protected] Phone: (61 8) 6304 6000 Web: ecu.edu.au/careers Email: [email protected] Equity, Diversity and Disability Service Web: intranet.ecu.edu.au/student/ support/it-support Phone: (61 8) 6304 6960 Email: [email protected] Emergencies and Campus Security Web: intranet.ecu.edu.au/student/ Phone: (61 8) 6304 3333 support/student-equity Email: [email protected] Student Health Services Web: ecu.edu.au/security Phone: Joondalup (61 8) 6304 5618 Kurongkurl Katitjin Phone: Mount Lawley (61 8) 9370 6814 Phone: (61 8) 6370 6689 Web: intranet.ecu.edu.au/student/ Email: [email protected] support/student-health Web: ecu.edu.au/centres/kurongkurl- Online booking available katitjin/overview Counselling Service University Contact Officers Phone: (61 8) 9370 6706 Web: ecu.edu.au/uco Email: [email protected] Web: ecu.edu.au/counselling 2 Message from the Vice-Chancellor Edith Cowan University (ECU) courses are All members of the ECU community are developed in consultation with industry, encouraged to familiarise themselves with, and our exceptional teaching staff have acknowledge and adopt, our University’s the industry experience and networks to guiding values. -

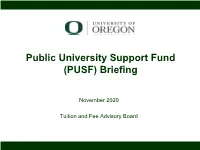

Public University Support Funding

Public University Support Fund (PUSF) Briefing November 2020 Tuition and Fee Advisory Board Discussion Topics • PUSF Overview • Comparative University Funding • Detailed Funding Categories • HECC Review of SSCM Model 2 PUSF Overview The PUSF is the state’s primary direct funding contribution for university operations and is distributed via the Student Success and Completion Model (SSCM). Components of PUSF: • Activity Based Funding: Student Credit Hours (SCH) • Outcomes Based Funding: Degrees & Certificates • Mission Differentiation Funding Other Non-PUSF funding streams: • State Programs • Statewide Public Service Programs • Sports Lottery 3 Comparative University Funding FY2020 EOU OIT OSU PSU SOU UO WOU Total Enrollment $3.5M $6.0M $47.4M $36.6M $5.5M $29.6M $7.8M $136.4M Based Outcomes $5.6M $9.4M $69.4M $58.9M $8.3M $41.5M $11.4M $204.6M Based Mission $11.8M $14.0M $18.0M $4.2M $8.9M $4.5M $7.6M $69.0M Differentiation State $0.2M $1.8M $14.3M $5.1M $0.2M $2.8M $0.3M $24.6M Programs State Wide $90.0M $90.0M Public Service Sports Lottery $1.2M $1.2M $0.5M $1.1M $1.2M $0.5M $1.2M $7.1M Total $22.4M $32.4M $239.6M $106.0M $24.1M $78.9M $28.4M $531.7M 4 Comparative University Funding FY2020 EOU OIT OSU PSU SOU UO WOU Total Fundable Students 1,547 2,136 18,249 15,393 2,383 12,825 3,404 55,937 PUSF Funding $21.0M $29.4M $134.8M $99.7M $22.7M $75.6M $26.8M $410.1M PUSF Funding Per Fundable $13,576 $13,775 $7,385 $6,478 $9,526 $5,897 $7,886 $7,331 Student Total Funding $22.4M $32.4M $239.6M $106.0M $24.1M $78.9M $28.4M $531.7M Total Funding -

Pocket Stats 2020 Pocket Stats 2020

WORLD READY- POCKET STATS 2020 POCKET STATS 2020 About ECU At Edith Cowan University, we are guided by our values of integrity, respect, rational inquiry, and personal excellence. ECU has been ranked Australia’s top public university for undergraduate teaching quality for the past six years, according to the QILT (Quality Indicators in Learning and Teaching) survey results. Our reputation for teaching quality was also highlighted in the 2021 Good Universities Guide, where ECU has achieved a five‑star rating for teaching quality for an amazing 14 years in a row. The University was ranked in the top 500 in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2021, an annual list of the top universities based on their teaching, research, and international outlook. ECU was granted university status in 1991, and has more than 31,000 undergraduate and postgraduate students, from over 100 countries. ECU has eight schools – Arts and Humanities; Business and Law; Education; Engineering; Medical and Health Sciences; Nursing and Midwifery; Science; and the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA) – delivering great learning experiences through a range of on‑campus and online courses. At a glance 31,409 20,654 Student Enrolments Student Load 2020 2020 (EFTSL) 7,360 1,979 Course Completions 2019 Total Staff 2020 (FTE) $17.8M $449.8M $485.2M Research Income 2019 Expenditure 2019 Revenue 2019 $57.3M 120.7 Capital Expenditure Total University Land Area 2019 2020 (ha) ECU WA campuses Student Enrolments1 2020 2019 By Gender Female 19,092 18,665 -

Going Public and Private Education Kit 2016

MONASH UNIVERSITY MUSEUM OF ART & Ten cubed Education kit Going PUblic and private Photo: Gleneagles Secondary College students, Ten Cubed 2015 Ground Floor, Building F www.monash.edu.au/muma Ten Cubed Monash University, Caulfield Campus Telephone +61 3 9905 4217 Telephone +61 3 9822 0833 900 Dandenong Road [email protected] 1489 Malvern Road, Glen Iris 3146 VIC Caulfield East VIC 3145 Australia Tues – Fri 10am – 5pm; Sat 12 – 5pm Tues – Sat 10am – 4pm MONASH UNIVERSITY MUSEUM OF ART & Ten cubed Education kit INTRODUCTION: GOING PUBLIC AND PRIVATE During gallery visits to both a Public University Art Museum (MUMA) and Private Collection (Ten Cubed) students meet arts professionals and compare how these two types of organisations manage their collections and develop exhibitions. Participants examine methods used to display and promote contemporary art and see the storerooms at both galleries to find out how artworks are cared for behind-the- scenes. CURRICULUM LINKS Going Public and Private is for students and teachers of VCE Studio Arts, Unit 4 Area of Study 3, Art Industry Contexts. Students are required to visit at least two different exhibition spaces as part of their studies. This program encompasses two gallery visits in a single excursion. BOOKINGS Going Public and Private tours operate Tuesday-Thursday throughout the school year by appointment. Programs are free and bookings are essential. The program can be offered as a walking tour or schools may opt to use their own transport. Contact: [email protected] ABOUT THIS RESOURCE This resource has been developed as curriculum support material for teachers and students.