[PDF] a Sand County Almanac

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

• Aldo Leopold, “The Land Ethic” (1948) • J. Baird Callicott, “Animal Liberation and Environmental Ethics: a Triangular Affair” (1980)

Lecture 10: Ecocentrism and Animal Liberation • Aldo Leopold, “The Land Ethic” (1948) • J. Baird Callicott, “Animal Liberation and Environmental Ethics: A Triangular Affair” (1980) Friday, October 11, 2013 Themes • “A triangular affair?” • Holism and individualism • Three differences between ecocentrism and animal liberation • Three arguments against animal liberation • Critique of ecocentrism Friday, October 11, 2013 Ecocentrism and Animal Liberation • Rift between ecocentrism (of Leopold) and animal liberation (of Singer) Friday, October 11, 2013 Ecocentrism and Animal Liberation • “A vegetarian human population is therefore probably ecologically catastrophic.” • “[Domestic animals] have been bred to docility, tractability, stupidity, and dependency. It is literally meaningless to suggest that they be liberated.” • “An imagined society in which all animals capable of sensibility received equal consideration or held rights to equal consideration would be so ludicrous that it might be more appropriately and effectively treated in satire than in philosophical discussion.” • “…the human population has become so disproportionate from the biological point of view that if one had to choose between a specimen of Homo sapiens and a specimen of a rare even if unattractive species, the choice would be moot.” Friday, October 11, 2013 Ecocentrism and Animal Liberation • Mountains, streams, and plants have as much ‘biotic right’ to exist as animals • Leopold never considers factory farming to be an urgent moral issue; exhibits apparent ‘indifference’ -

Envisioning Democracy Through Aldo Leopold's Land Ethic Stacey L

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2013 The eD mocratic Landscape: Envisioning Democracy Through Aldo Leopold's Land Ethic Stacey L. Matrazzo [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Matrazzo, Stacey L., "The eD mocratic Landscape: Envisioning Democracy Through Aldo Leopold's Land Ethic" (2013). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 45. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/45 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Democratic Landscape: Envisioning Democracy Through Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Stacey L. Matrazzo May, 2013 Mentor: Dr. R. Bruce Stephenson Reader: Dr. Leslie K. Poole Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida Table of Contents Introduction..........................................................................................................................2 The Land Ethic’s Role in Democracy..................................................................................5 The Evolution of the Land Ethic........................................................................................17 -

Spirited Away Picture Book Free Ebook

FREESPIRITED AWAY PICTURE BOOK EBOOK Hayao Miyazaki | 170 pages | 01 Sep 2008 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781569317969 | English | San Francisco, United States VIZ | See Spirited Away Picture Book Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. This illustrated book tells the story of the animated feature film Spirited Away. Driving to their new home, Mom, Dad, and their daughter Chihiro take a wrong turn. In a strange abandoned amusement park, while Chihiro wanders away, her parents Spirited Away Picture Book into pigs. She must then find her way in a world inhabited by ghosts, demons, and strange gods. Get A Copy. Hardcoverpages. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Spirited Away Spirited Away Picture Book Bookplease sign up. Be the first to ask a question about Spirited Away Picture Book. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. Sort order. Start your review of Spirited Away Picture Book. I bought this picture book a long time ago. I was looking for some in depth books or manga on my favorite movie of all time, Spirited Away by Hayao Miyazaki. I will be adding several gifs of the movie toward the end but they are in no kind of order. -

Developing a Sustainable Land Ethic in 21St Century Cities

Eco-Architecture IV 139 Developing a sustainable land ethic in 21st century cities G. E. Kirsch Department of English and Media Studies, Bentley University, USA Abstract As more and more of the world’s population lives in urban environments, we are faced with questions of quality of life, urban regeneration, sustainability and living in harmony with nature. Drawing on the work of Aldo Leopold, one of the most renowned figures in conservation, wildlife ecology, and environmental ethics, I argue that we need to develop an urban land ethic, one that pays attention to how access to land and water fronts, to parks and playgrounds is intimately tied to health, safety, recreation, and the ability of families to raise children in an urban environment. I use a specific local example from Boston, Massachusetts (USA) to illustrate my argument: I examine the Boston Esplanade Association’s 2020 Vision Study that articulates the importance of parklands, recreation, ecology, and nature for city residents. Keywords: urban land ethic, Aldo Leopold, quality of life, families in cities, parklands and green spaces, sustainable cities, Esplanade 2020 Vision, Boston USA. 1 Introduction Developing an urban land ethic will become critical to the success and survival of future cities. UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon, in his commentary on the second Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, argues, “At Rio, governments should call for smarter use of resources. Our oceans much be protected. So must our water, air and forests. Our cities must be made more liveable – places we inhabit in greater harmony with nature” [1]. As more and more of the world’s population lives in urban environments, we are faced with questions of quality of life, urban regeneration, sustainability and living in harmony with nature. -

The-Odyssey-Greek-Translation.Pdf

05_273-611_Homer 2/Aesop 7/10/00 1:25 PM Page 273 HOMER / The Odyssey, Book One 273 THE ODYSSEY Translated by Robert Fitzgerald The ten-year war waged by the Greeks against Troy, culminating in the overthrow of the city, is now itself ten years in the past. Helen, whose flight to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris had prompted the Greek expedition to seek revenge and reclaim her, is now home in Sparta, living harmoniously once more with her husband Meneláos (Menelaus). His brother Agamémnon, commander in chief of the Greek forces, was murdered on his return from the war by his wife and her paramour. Of the Greek chieftains who have survived both the war and the perilous homeward voyage, all have returned except Odysseus, the crafty and astute ruler of Ithaka (Ithaca), an island in the Ionian Sea off western Greece. Since he is presumed dead, suitors from Ithaka and other regions have overrun his house, paying court to his attractive wife Penélopê, endangering the position of his son, Telémakhos (Telemachus), corrupting many of the servants, and literally eating up Odysseus’ estate. Penélopê has stalled for time but is finding it increasingly difficult to deny the suitors’ demands that she marry one of them; Telémakhos, who is just approaching young manhood, is becom- ing actively resentful of the indignities suffered by his household. Many persons and places in the Odyssey are best known to readers by their Latinized names, such as Telemachus. The present translator has used forms (Telémakhos) closer to the Greek spelling and pronunciation. -

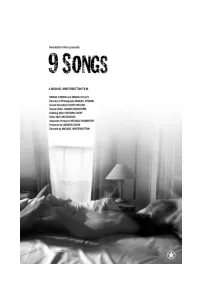

9 SONGS-B+W-TOR

9 SONGS AFILMBYMICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM One summer, two people, eight bands, 9 Songs. Featuring exclusive live footage of Black Rebel Motorcycle Club The Von Bondies Elbow Primal Scream The Dandy Warhols Super Furry Animals Franz Ferdinand Michael Nyman “9 Songs” takes place in London in the autumn of 2003. Lisa, an American student in London for a year, meets Matt at a Black Rebel Motorcycle Club concert in Brixton. They fall in love. Explicit and intimate, 9 SONGS follows the course of their intense, passionate, highly sexual affair, as they make love, talk, go to concerts. And then part forever, when Lisa leaves to return to America. CAST Margo STILLEY AS LISA Kieran O’BRIEN AS MATT CREW DIRECTOR Michael WINTERBOTTOM DP Marcel ZYSKIND SOUND Stuart WILSON EDITORS Mat WHITECROSS / Michael WINTERBOTTOM SOUND EDITOR Joakim SUNDSTROM PRODUCERS Andrew EATON / Michael WINTERBOTTOM EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Andrew EATON ASSOCIATE PRODUCER Melissa PARMENTER PRODUCTION REVOLUTION FILMS ABOUT THE PRODUCTION IDEAS AND INSPIRATION Michael Winterbottom was initially inspired by acclaimed and controversial French author Michel Houellebecq’s sexually explicit novel “Platform” – “It’s a great book, full of explicit sex, and again I was thinking, how come books can do this but film, which is far better disposed to it, can’t?” The film is told in flashback. Matt, who is fascinated by Antarctica, is visiting the white continent and recalling his love affair with Lisa. In voice-over, he compares being in Antarctica to being ‘two people in a bed - claustrophobia and agoraphobia in the same place’. Images of ice and the never-ending Antarctic landscape are effectively cut in to shots of the crowded concerts. -

'Slut I Hate You': a Critical Discourse Analysis of Gendered Conflict On

1 ‘Slut I hate you’: A Critical Discourse Analysis of gendered conflict on YouTube Sagredos Christos, Nikolova Evelin Abstract Research on gendered conflict, including language aggression against women has tended to focus on the analysis of discourses that sustain violence against women, disregarding counter-discourses on this phenomenon. Adopting a Critical Discourse Analysis perspective, this paper draws on the Discourse Historical Approach to examine the linguistic and discursive strategies involved in the online conflict that emerges from the polarisation of discourses on violence against women. An analysis of 2,304 consecutive YouTube comments posted in response to the sexist Greek song Καριόλα σε μισώ ‘Slut I hate you’ revealed that conflict revolves around five main topics: (a) gendered aggression, (b) the song, (c) the singer, (d) other users’ reactions to the song and (e) contemporary socio-political concerns. Findings also suggest that commenters favouring patriarchal gender ideologies differ in the lexicogrammatical choices and discursive strategies they employ from those who challenge them. Keywords: violence against women, language aggression, conflicting discourses, conflict on YouTube 2 1. Introduction The proliferation of online public spaces through social media can among others be seen as some kind of opening the “access to prestigious discourse types” and, therefore, as offering a greater or lesser potential for “democratisation of public discourse” (Fairclough 1992, 201). However, there is little consensus about the democratic potential afforded by such new technologies. While some focus on the plurality of voices that are allowed to be heard and the diverse identities that may gain visibility, others highlight that anonymity in digitally mediated communication may foster a feeling of unaccountability, thus reinforcing online incivility and polarisation of ideas (Garcés-Conejos Blitvich 2010; Papacharissi 2009; van Zoonen et al. -

Boys and Girls by Alice Munro

Boys and Girls by Alice Munro My father was a fox farmer. That is, he raised silver foxes, in pens; and in the fall and early winter, when their fur was prime, he killed them and skinned them and sold their pelts to the Hudson's Bay Company or the Montreal Fur Traders. These companies supplied us with heroic calendars to hang, one on each side of the kitchen door. Against a background of cold blue sky and black pine forests and treacherous northern rivers, plumed adventures planted the flags of England and or of France; magnificent savages bent their backs to the portage. For several weeks before Christmas, my father worked after supper in the cellar of our house. The cellar was whitewashed, and lit by a hundred-watt bulb over the worktable. My brother Laird and I sat on the top step and watched. My father removed the pelt inside-out from the body of the fox, which looked surprisingly small, mean, and rat-like, deprived of its arrogant weight of fur. The naked, slippery bodies were collected in a sack and buried in the dump. One time the hired man, Henry Bailey, had taken a swipe at me with this sack, saying, "Christmas present!" My mother thought that was not funny. In fact she disliked the whole pelting operation--that was what the killing, skinning, and preparation of the furs was called – and wished it did not have to take place in the house. There was the smell. After the pelt had been stretched inside-out on a long board my father scraped away delicately, removing the little clotted webs of blood vessels, the bubbles of fat; the smell of blood and animal fat, with the strong primitive odour of the fox itself, penetrated all parts of the house. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Books to Feed the Mind & Soul

Books to Feed the Mind & Soul Audubon Rockies staff and Colorado Chapter leaders were asked to share some of their favorite books. Listed below are a mix of nature-oriented, conservation-minded, humorous, and engaging reads. As we continue to find ourselves practicing social distancing, especially in these colder months, chapter leaders are welcome to use this list for their personal enjoyment or pull from it to share with chapter members in newsletter articles. Or perhaps for a book club or a reading list for your local library? The following books are provided in no particular order. Additional information listed for some books are a mix of details gleaned from online searches as well as those graciously provided by the original contributor. The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century by Kirk Wallace Johnson - A nonfiction tale of the British Museum of Natural History, home to one of the largest ornithological collections in the world, and obsession, nature, and man's unrelenting desire to lay claim to its beauty. Vulture: The Private Life of an Unloved Bird by Katie Fallon Signature of All Things by Elizabeth Gilbert A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration by Kenn Kaufman The Genius of Birds and The Bird Way by Jennifer Ackerman The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man's Love Affair with Nature by J. Drew Lanham - From these fertile soils—of love, land, identity, family, and race—emerges The Home Place, a big-hearted, unforgettable memoir by ornithologist J. Drew Lanham. A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds by Scott Weidensaul Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology by David Abram The Big Year: A Tale of Man, Nature, and Fowl Obsession by Mark Obmascik - Journalist Mark Obmascik creates a dazzling, fun narrative of the 275,000-mile odyssey of these three obsessives as they fight to win the greatest— or maybe worst—birding contest of all time. -

Relationship Between Foreign Film Exposure And

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FOREIGN FILM EXPOSURE AND ETHNOCENTRISM LINGLI YING Bachelor of Arts in English Literature Zhejiang University, China July, 2003 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirement for the degree MASTER OF APPLIED COMMUNICATION THEORY AND METHODOLOGY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY MAY, 2009 1 THESIS APPROVAL SCHOOL OF COMMUNICATION This thesis has been approved for the School of Communication And the College of Graduates Studies by: Kimberly A. Neuendorf Thesis Committee Chairman School of Communication 5/13/09 (Date) Evan Lieberman Committee Member School of Communication 5/13/09 (Date) George B. Ray Committee Member School of Communication 5/13/09 (Date) 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my special thanks to my advisor, Dr. Kimberly Neuendorf, who provided me with detailed and insightful feedback for every draft, who spent an enormous amount of time reading and editing my thesis, and more importantly, who set an example for me to be a rigorous scholar. I also want to thank her for her encouragement and assistance throughout the entire graduate program. I would also like to thank Dr. Evan Lieberman for his assistance and suggestions in helping me to better understand the world cinema and the cinema culture. Also, I want to thank him for his great encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. I want to offer a tremendous thank you to Dr. Gorge Ray. I learned so much about American people and culture from him and also in his class. I will remember his patience and assistance in helping me finish this program. I am also grateful for all the support I received from my friends and my officemates. -

ADJS Top 200 Song Lists.Xlsx

The Top 200 Australian Songs Rank Title Artist 1 Need You Tonight INXS 2 Beds Are Burning Midnight Oil 3 Khe Sanh Cold Chisel 4 Holy Grail Hunter & Collectors 5 Down Under Men at Work 6 These Days Powderfinger 7 Come Said The Boy Mondo Rock 8 You're The Voice John Farnham 9 Eagle Rock Daddy Cool 10 Friday On My Mind The Easybeats 11 Living In The 70's Skyhooks 12 Dumb Things Paul Kelly 13 Sounds of Then (This Is Australia) GANGgajang 14 Baby I Got You On My Mind Powderfinger 15 I Honestly Love You Olivia Newton-John 16 Reckless Australian Crawl 17 Where the Wild Roses Grow (Feat. Kylie Minogue) Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds 18 Great Southern Land Icehouse 19 Heavy Heart You Am I 20 Throw Your Arms Around Me Hunters & Collectors 21 Are You Gonna Be My Girl JET 22 My Happiness Powderfinger 23 Straight Lines Silverchair 24 Black Fingernails, Red Wine Eskimo Joe 25 4ever The Veronicas 26 Can't Get You Out Of My Head Kylie Minogue 27 Walking On A Dream Empire Of The Sun 28 Sweet Disposition The Temper Trap 29 Somebody That I Used To Know Gotye 30 Zebra John Butler Trio 31 Born To Try Delta Goodrem 32 So Beautiful Pete Murray 33 Love At First Sight Kylie Minogue 34 Never Tear Us Apart INXS 35 Big Jet Plane Angus & Julia Stone 36 All I Want Sarah Blasko 37 Amazing Alex Lloyd 38 Ana's Song (Open Fire) Silverchair 39 Great Wall Boom Crash Opera 40 Woman Wolfmother 41 Black Betty Spiderbait 42 Chemical Heart Grinspoon 43 By My Side INXS 44 One Said To The Other The Living End 45 Plastic Loveless Letters Magic Dirt 46 What's My Scene The Hoodoo Gurus