Lecture7 Reading.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home Appliance Cautious Buy

Sector Research | China Home Appliance THIS IS THE TRANSLATION OF A REPORT ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN CHINESE BY GUOSEN SECURITIES CO., LTD ON SEPTEMBER 24, 2012 October 16, 2012 Home Appliance Cautious Buy Cherry pick home-appliance names amid the price corrections Investment highlights Analyst Wang Nianchun We expect home-appliance y-o-y sales volume growth to rebound moderately +755-82130407 in 4Q 2012. Based on our channel checks and data already released for Jul-Aug [email protected] S0980510120027 2012, 3Q sales volume of various sub-sectors was in line with expectations, and the profitability of the TV sub-sector slightly beat expectations. The subsidies for energy efficient home-appliance products introduced in June are unlikely to materially boost sales until three to six months after their launch. We expect the 4Q y-o-y sales Sales Contact volume growth of air conditioners, refrigerators, washing machines and LCD TVs will be 7.5%, 5.8%, 5.0% and 0.8% respectively, representing a modest rebound from the Roger Chiman Managing Director first three quarters. +852 2248 3598 [email protected] Divergence within the sector intensifies, and we suggest waiting for buying Chris Berney opportunities amid price pullbacks. The overall industry sentiment has been tepid Managing Director +852 2248 3568 since the beginning of 2012, but product-mix upgrade and lower material costs could lead [email protected] to an improvement in profitability this year. Based on our estimates, subsidy policies for Andrew Collier energy efficient home-appliance products will have more significant effects in 2013 than Director +852 2248 3528 this year. -

STOXX Greater China 480 Last Updated: 01.04.2015

STOXX Greater China 480 Last Updated: 01.04.2015 Rank Rank (PREVIOUS ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) ) TW0002330008 6889106 2330.TW TW001Q TSMC TW TWD Y 105.1 1 1 KYG875721634 BMMV2K8 0700.HK B01CT3 Tencent Holdings Ltd. CN HKD Y 92.5 2 2 HK0000069689 B4TX8S1 1299.HK HK1013 AIA GROUP HK HKD Y 70.6 3 4 HK0941009539 6073556 0941.HK 607355 China Mobile Ltd. CN HKD Y 64.3 4 3 CNE1000002H1 B0LMTQ3 0939.HK CN0010 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H CN HKD Y 61.8 5 5 CNE1000003G1 B1G1QD8 1398.HK CN0021 ICBC H CN HKD Y 52.5 6 6 CNE1000001Z5 B154564 3988.HK CN0032 BANK OF CHINA 'H' CN HKD Y 40.9 7 7 TW0002317005 6438564 2317.TW TW002R Hon Hai Precision Industry Co TW TWD Y 35.1 8 8 CNE1000002L3 6718976 2628.HK CN0043 China Life Insurance Co 'H' CN HKD Y 30.3 9 9 HK0013000119 6448068 0013.HK 644806 Hutchison Whampoa Ltd. HK HKD Y 26.2 10 10 CNE1000003X6 B01FLR7 2318.HK CN0076 PING AN INSUR GP CO. OF CN 'H' CN HKD Y 25.3 11 19 HK0388045442 6267359 0388.HK 626735 Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing HK HKD Y 25.2 12 12 KYG217651051 BW9P816 0001.HK 619027 CK HUTCHISON HOLDINGS HK HKD Y 25.0 13 11 CNE1000003W8 6226576 0857.HK CN0065 PetroChina Co Ltd 'H' CN HKD Y 21.7 14 13 HK0883013259 B00G0S5 0883.HK 617994 CNOOC Ltd. CN HKD Y 20.9 15 15 HK0016000132 6859927 0016.HK 685992 Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd. -

2016Semi-Annual Report

CHINA CONVERGENCE FUND A Sub-fund of Value Partners Intelligent Funds SEMI-ANNUAL 2016 REPORT For the six months ended 30 June 2016 Value Partners Limited 9th Floor, Nexxus Building 41 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong Tel: (852) 2880 9263 Fax: (852) 2565 7975 Email: [email protected] Website: www.valuepartners-group.com In the event of inconsistency, the English text of this Semi-Annual Report shall prevail over the Chinese text. This report shall not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy shares in any of the funds. Subscriptions are to be made only on the basis of the information contained in the explanatory memorandum, as supplemented by the latest semi-annual and annual reports. CHINA CONVERGENCE FUND A Sub-fund of Value Partners Intelligent Funds (A Cayman Islands unit trust) CONTENTS Pages General information 2-3 Manager’s report 4-9 Statement of financial position (unaudited) 10 Investment portfolio (unaudited) 11-15 Investment portfolio movements (unaudited) 16 SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT 2016 For the six months ended 30 June 2016 1 CHINA CONVERGENCE FUND A Sub-fund of Value Partners Intelligent Funds (A Cayman Islands unit trust) GENERAL INFORMATION Manager Legal Advisors Value Partners Limited With respect to Cayman Islands law 9th Floor, Nexxus Building Maples and Calder 41 Connaught Road Central 53rd Floor, The Center Hong Kong 99 Queen’s Road Central Hong Kong Directors of the Manager Dato’ Seri Cheah Cheng Hye With respect to Hong Kong law Mr. Ho Man Kei, Norman King & Wood Mallesons Mr. So Chun Ki Louis 13th Floor, Gloucester Tower The Landmark Trustee, Registrar, Administrator and 15 Queen’s Road Central Principal Office Hong Kong Bank of Bermuda (Cayman) Limited P.O. -

Phase Exhibitior Section Stand Number 1 SASSIN INTERNATIONAL ELECTRIC SHANGHAI CO.,LTD

VIP Exhibitors of the 114th Session of Canton Fair Phase Exhibitior Section Stand Number 1 SASSIN INTERNATIONAL ELECTRIC SHANGHAI CO.,LTD. Electronic and Electrical Products 5.1A09-22 1 SICHUAN JIUZHOU ELECTRIC GROUP CO., LTD. Consumer Electronics 11.3C35-46 1 Guangzhou Midea Hualing Refrigerator Co., Ltd. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2A77-92 1 GREE ELECTRIC APPLIANCES,INC.OF ZHUHAI Household Electrical Appliances 4.2A51-78 1 MIDEA GROUP CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2A09-60 1 HAIER GROUP Household Electrical Appliances 3.2B01-54 1 GUANGDONG XINBAO APPLIANCES HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 4.2F31-47 1 NO.168 HUANCHENG EAST RD.ZHOUXIANG CIXI,NINGBO P.R.C. Household Electrical Appliances 4.2F19-30 1 NINGBO AUX IMP.& EXP CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 4.2D13-46 1 XINGXING GROUP CO.,LTD Household Electrical Appliances 4.2I07-21 1 TCL CORPORATION Household Electrical Appliances 3.2G41-60 1 GUANGDONG GALANZ ENTERPRISE CO., LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 4.2A06-45 1 Guangzhou Wanbao Group Co.,Ltd. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2E50-67 1 GUANGDONG CHIGO AIR CONDITIONING CO.LTD Household Electrical Appliances 4.2D51-71 1 Homa Appliances Co., Ltd Household Electrical Appliances 3.2C01-12 1 NINGBO KAIBO GROUP CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 2.2D37-42,2.2E07-12 1 NINGBO XINLE HOUSEHOLD APPLIANCES CO., LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2C85-96 1 SICHUAN CHANGHONG ELECTRIC CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2E20-35 1 NINGBO LAMO ELECTRIC APPLIANCE CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2G29-40 1 HEFEI MEILING COMPANY LIMITED Household Electrical Appliances 3.2E36-49 1 CUORI ELECTRICAL APPLICANAES GROUP CO.,LTD. -

Annual Report 2009/10

Skyworth Digital Holdings Limited Annual Report 2009/10 Contents Financial Highlights 2 Letter from Executive Chairman and Chief Executive Officer 4 Management Discussion and Analysis 8 Corporate Governance Report 21 Directors and Senior Management Profiles 33 Corporate Structure 41 Investor Relations 42 Directors’ Report 47 Independent Auditor’s Report 60 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 63 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 65 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 67 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 69 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 71 Summarised Statement of Financial Position of the Company 163 Financial Summary 164 Financial Review 165 Corporate Information 166 1 Skyworth Digital Holdings Limited Annual Report 2009/10 Financial Highlights Amount expressed in HK$ million (except for share data) 2010 2009 Change OPERATING RESULTS FROM CONTINUING OPERATIONS Turnover 22,769 15,329 +48.5% Operating Profit (EBIT) from continuing operations 1,660 700 +137.1% Profit from continuing operations 1,326 460 +188.3% DISCONTINUED OPERATIONS Gain (loss) for the year from discontinued operation – 43 -100.0% Net Profit for the year 1,326 503 +163.6% Profit attributable to owners of the Company 1,251 460 +172.0% FINANCIAL POSITION Net cash (used in) from operating activities (1,987) 794 -350.3% Cash position* 4,585 1,539 -52.8% Bank loans 6,721 1,429 +197.9% Bank loans excluding the financial liabilities arising from discounted bills and foreign exchange arrangements 968 147 +558.5% Equity attributable -

Global Powers of Consumer Products 2015 Connecting

Global Powers of Consumer Products 2015 Connecting with the connected consumer Contents Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited (DTTL) is pleased to present the eighth annual Global Powers of Consumer Welcome 5 Global economic outlook 6 Products. This report identifies the 250 largest consumer Connecting with the connected consumer 11 products companies around the world based on publicly Global Powers of Consumer Products Top 250 17 available data for the fiscal year 2013 (encompassing Top 250 highlights 19 companies’ fiscal years ended through June 2014). Top 10 21 Geographic analysis 22 Product sector analysis 25 The report also provides an outlook on the global Top 250 newcomers 29 economy; an analysis of market capitalization in the Fastest 50 31 industry; a look at merger & acquisition activity in the M&A activity 32 Q ratio analysis 37 consumer products industry; and a discussion on the Study methodology and data sources 40 importance of connecting with the connected consumer. Contacts 41 Global Powers of Consumer Products 2015 2 Global Powers of Consumer Products 2015 3 Global economic outlook Big global issues What can we expect going forward? In the short term, it is likely dollar could be problematic for companies in emerging countries Second, the government has attempted to limit the growth of the housing. Data have bounced around in the past year due to higher Europe that the price of oil will fall further. There is a considerable amount that have dollar-denominated debts. The volume of such debt has shadow banking system. Lending outside traditional banking chan- mortgage interest rates, higher house prices, and the fact that The Eurozone economy has been in very poor shape and prices are Falling oil price of new oil production already in the pipeline in the U.S. -

Company Name(Ecountry Hall No

Company name(ECountry Hall No. Booth No. Email Website Project/ProductE-mail Name(English)Website superpix Micro Tchina 5 ZKY10 [email protected] image sensor chip typical application demonstration project Sanjin group hunchina 9 9S33 hnsanjin@ www.hnsanjin.com SLon Magnetic chinaS 9 9s35 annabelee www.slon.cIndustrialisation of SLon HGMS series Institute of Mic china 5 ZKY11 [email protected] HMotor Controller for Variable Frequency Air Conditioner Tsinghua Universchina 8 8G06 [email protected] [email protected] Tsinghua Universchina 8 8G06 [email protected] Organic [email protected] Tsinghua Universchina 8 8G06 [email protected] [email protected] Tsinghua Universchina 8 8G06 [email protected] Broadband jsong@tsinhttp://riit.tsinghua.edu.cn Jiangxi Gao'an china 9 9s35 sale@htgjledHttp://www.LED [email protected] Hunan Hongyingxchina 9 9S33 36913613 hyxbio.comEnzyme Pre36913613 hyxbio.com china 9 9s35 [email protected] www.707hitech.com china 9 9s35 [email protected] www.707hitech.com JIUJIANG LISHANchina ENTECH9 CO., LTD.9s35 [email protected] JIUJIANG LISHANchina ENTECH9 CO., LTD.9s35 [email protected] JIANGXI CHEN china 9 9S35 [email protected] JIANGXI CHEN china 9 9S35 [email protected] jiangxi Longzhe china 9 9S35 jxlz2008@ http://www “JX-108”Nejxlz2008@ http://www.jxlongzheng.com china 9 9S35 [email protected] [email protected] Jiangxi Academychina 9 9S35 [email protected] The [email protected] Jiangxi Academychina 9 9S35 [email protected] the [email protected] Jiangxi Academychina 9 9S35 [email protected] Hihg-purity [email protected] Jiangxi Academychina 9 9S35 [email protected] Hihg-purity [email protected] Jiangxi Academychina 9 9S35 [email protected] GAP planti [email protected] wuhan universit china 8 8G10 [email protected]. -

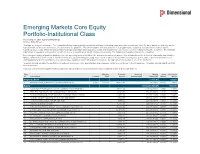

Emerging Markets Core Equity Portfolio-Institutional Class As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings Are Subject to Change

Emerging Markets Core Equity Portfolio-Institutional Class As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings are subject to change. The information below represents the portfolio's holdings (excluding cash and cash equivalents) as of the date indicated, and may not be representative of the current or future investments of the portfolio. The information below should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding any security. This listing of portfolio holdings is for informational purposes only and should not be deemed a recommendation to buy the securities. The holdings information below does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. The holdings information has not been audited. By viewing this listing of portfolio holdings, you are agreeing to not redistribute the information and to not misuse this information to the detriment of portfolio shareholders. Misuse of this information includes, but is not limited to, (i) purchasing or selling any securities listed in the portfolio holdings solely in reliance upon this information; (ii) trading against any of the portfolios or (iii) knowingly engaging in any trading practices that are damaging to Dimensional or one of the portfolios. Investors should consider the portfolio's investment objectives, risks, and charges and expenses, which are contained in the Prospectus. Investors should read it carefully before investing. Your use of this website signifies that you agree to follow and be bound by the terms -

OEM and EMS: a Market and Competitive Analysis - 2016 Edition

OEM and EMS: A Market and Competitive Analysis - 2016 Edition A Unique Report Combining In-Depth Review of 360 OEMs’ Outsourced Electronics Assembly and Market Share Analysis of 48 Product Segments of the 100 Largest EMS Subcontractors Report Highlights Market Share by Product Segment Analysis, 2015 Automotive Communications Computers/Peripherals Consumer Electronics Industrial Medical Aerospace/Defense/Other Transportation OEM and EMS Company-Level Analysis, 2015 360 Electronic OEM Companies 100 Largest EMS Companies Outsourced/In-House Assembly Revenue Assembly Revenue by 48 Product Segments New Venture Research Corp. A Technology Market Research Company 337 Clay St., Suite 101 info@newventureresearch .com Tel: (530) 265-2004 Fax: (530) 265-1998 OEM and EMS: A Market and Competitive Analysis - 2016 Edition Synopsis The worldwide electronics assembly market is An example can be provided for the smart phone substantial, the cost of goods sold (COGS) reached market for Apple. Whereas Apple’s EMS partners approximately $1.3 trillion dollars by 2015. The are well known, most industry participants are less market is growing but changing in terms EMS aware of other OEMs’ subcontractors which include suppliers’ market share. This report establishes the Blackberry, Lenovo, Microsoft, NEC, Sony, Toshiba, market share of the leading 100 EMS suppliers to Xiaomi, and ZTE. This report provides market share over 360 OEMs competing in 48 different markets. information on over 360 OEMs across 48 product It is the first of its kind and utilizes NVR's unique segments served by the leading 100 EMS firms. database of supplier and contractor data showing the market share of the total available EMS market. -

The New Global Challengers

The New Global Challengers How 100 Top Companies from Rapidly Developing Economies Are Changing the World BCG REPORT Since its founding in 1963, The Boston Consulting Group has focused on helping clients achieve competitive advantage. Our firm believes that best practices or benchmarks are rarely enough to create lasting value and that positive change requires new insight into economics, markets, and organizational dynamics. We consider every assignment a unique set of opportunities and constraints for which no standard solution will be adequate. BCG has 61 offices in 36 countries and serves companies in all industries and markets. For further information, please visit our Web site at www.bcg.com. The New Global Challengers How 100 Top Companies from Rapidly Developing Economies Are Changing the World MARCOS AGUIAR ARINDAM BHATTACHARYA THOMAS BRADTKE PASCAL COTTE STEPHAN DERTNIG MICHAEL MEYER DAVID C. MICHAEL HAROLD L. SIRKIN MAY 2006 www.bcg.com © The Boston Consulting Group, Inc. 2006. All rights reserved. For information or permission to reprint, please contact BCG at: E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +1 617 973 1339, attention BCG/Permissions Mail: BCG/Permissions The Boston Consulting Group, Inc. Exchange Place Boston, MA 02109 USA 2 BCG REPORT Table of Contents A Word from the Authors 4 The New Global Challenge 5 Many Companies on the Move 5 RDEs as Platforms for New Types of Global Competitors 6 The RDE 100 Emerging Global Challengers 7 Where They Come From 8 The Industries They Represent 9 Why They Are Going Global 9 Their Huge Economic -

Skyworth Digital Target Price: HKD5.90 Price: HKD4.66 Set for a Strong Recovery Ahead Market Cap: USD1,818M Bloomberg Ticker: 751 HK

Results Review Hong Kong FY17: below expectations 15 June 2017 Technology | Hardware & Equipment Buy (Maintained) Skyworth Digital Target Price: HKD5.90 Price: HKD4.66 Set For a Strong Recovery Ahead Market Cap: USD1,818m Bloomberg Ticker: 751 HK We continue to expect Skyworth to see a solid recovery this year. We Share Data expect its profitability to see meaningful improvement, driven by: Avg Daily Turnover (HKD/USD) 53.8m/6.84m 1. Rebound of its GPM (due to panel price moderating and an increase in 52-wk Price low/high (HKD) 4.17 - 6.35 blended ASP of its core China TV sales); 2. Better operating leverage (due to better revenue growth momentum) Free Float (%) 59 and better cost control. Shares outstanding (m) 2,837 Therefore, maintain BUY, with a lower HKD5.90 TP (from HKD6.40, 27% Estimated Return 27% upside) as we cut our earnings forecasts for FY18F-19F by 7-8% to factor in a more conservative blended ASP growth of its core China TV sales. Shareholders (%) Wong Wai Sen, Stephen 36.1 Skyworth Digital’s (Skyworth) profitability to improve meaningfully this year, driven by: Alliance Bernstein LP 5.0 i. Rebound of GPM. According to data from WitsView Technology Coperation (Witsview), the pricing of major sizes of thin film transistor Share Performance (%) liquid crystal display (TFT LCD) have already shown signs of peaking in recent months. Given that the new capacity is kicking in, IHS Markit (IHS) YTD 1m 3m 6m 12m expects that panel pricing to start dropping in 2H17. Absolute 5.4 7.4 (12.9) 7.1 (5.3) Based on our discussion with management previously, a YoY growth in the Relative (12.1) 4.6 (21.4) (8.0) (32.1) blended ASP of its core China TV sales have risen further to a high single Source: Bloomberg digit in recent months. -

China's Impact on the Semiconductor Industry: 2011 Update MEPTEC

www.pwc.com/technology China’s impact on the semiconductor industry: 2011 update MEPTEC – January 2012 Worldwide semiconductor market by region, 2003-2010 Source: SIA, CCID PwC 2 China's semiconductor market growth, 2000-2010 PwC 3 Comparison of China vs. worldwide semiconductor growth by quarter, 2007-2010 PwC 4 China's IC and O-S-D market growth, 2000-2010 PwC 5 China compared with worldwide semiconductor market by application, 2010 PwC 6 Semiconductor suppliers to the Chinese market, 2009-2010 Rank Revenue in millions of US dollars Market share Company 2009 2010 2009 IC 2010 IC % Change 2009 Semi 2010 Semi % Change Intel 1 1 15,570 19,659 26.3% 15,570 19,659 26.3% 14.9% Samsung 2 2 5,548 8,018 44.5% 5,681 8,175 43.9% 6.2% Hynix 4 3 3,644 5,564 52.7% 3,644 5,564 52.7% 4.2% Toshiba 3 4 3,231 4,138 28.1% 3,904 4,970 27.3% 3.8% TI 7 5 3,127 4,248 35.8% 3,292 4,479 36.1% 3.4% ST 5 6 2,704 3,305 22.2% 3,601 4,449 23.5% 3.4% AMD 6 7 3,415 4,174 22.2% 3,415 4,174 22.2% 3.2% NXP 8 8 2,281 2,965 30.0% 2,891 3,751 29.7% 2.8% Renesas* 12 1,272 1,716 9 2,634 31.0% 3,484 32.6% 2.6% NEC* 18 739 911 Freescale 10 10 2,057 2,788 35.5% 2,436 3,233 32.7% 2.4% Media Tek (MTK) 9 12 2,442 2,453 0.5% 2,442 2,453 0.5% 1.9% Total Top 10 44,019 57,493 30.6% 46,876 61,938 32.1% 46.9% Total Top 10 share of Chinese integrated circuit market 53.0% 52.9% Chinese semiconductor market 46.3% 46.9% Note: Semi equals IC + Discrete (including LED) market.