7. Sue Sylvester, Coach Beiste, Santana Lopez, and Unique Adams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M-Ad Shines in Toronto

Volume 44, Issue 3 SUMMER 2013 A BULLETIN FOR EVERY BARBERSHOPPER IN THE MID-ATLANTIC DISTRICT M-AD SHINES IN TORONTO ALEXANDRIA MEDALS! DA CAPO maKES THE TOP 10 GImmE FOUR & THE GOOD OLD DAYS EARN TOP 10 COLLEGIATE BROTHERS IN HARMONY, VOICES OF GOTHam amONG TOP 10 IN THE WORLD WESTCHESTER WOWS CROWD WITH MIC-TEST ROUTINE ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT, FRANK THE DOG HIT TOP 20 UP ALL NIGHT KEEPS CROWD IN STITCHES CHORUS OF THE CHESAPEAKE, BLACK TIE AFFAIR GIVE STRONG PERFORmaNCES INSIDE: 2-6 OUR INTERNATIONAL COMPETITORS 7 YOU BE THE JUDGE 8-9 HARMONY COLLEGE EAST 10 YOUTH CamP ROCKS! 11 MONEY MATTERS 12-15 LOOKING BACK 16-19 DIVISION NEWS 20 CONTEST & JUDGING YOUTH IN HARMONY 21 TRUE NORTH GUIDING PRINCIPLES 23 CHORUS DIRECTOR DEVELOPMENT 24-26 YOUTH IN HARMONY 27-29 AROUND THE DISTRICT . AND MUCH, MUCH MORE! PHOTO CREDIT: Lorin May ANYTHING GOES! 3RD PLACE BRONZE MEDALIST ALEXANDRIA HARMONIZERS PULL OUT ALL THE STOPS ON STAGE IN TORONTO. INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION 2013: QUARTET CONTEST ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT, T.J. Carollo, Jeff Glemboski, Larry Bomback and Wayne Grimmer placed 12th. All photos courtesy of Dan Wright. To view more photos, go to www. flickr.com/photosbydanwright UP ALL NIGHT, John Ward, Cecil Brown, Dan Rowland and Joe Hunter placed 28th. DA CAPO, Ryan Griffith, Anthony Colosimo, Wayne FRANK THE Adams and Joe DOG, Tim Sawyer placed Knapp, Steve 10th. Kirsch, Tom Halley and Ross Trube placed 20th. MID’L ANTICS SUMMER 2013 pa g e 2 INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION 2013: COLLEGIATE QUARTETS THE GOOD OLD DAYS, Fernando Collado, Doug Carnes, Anthony Arpino, Edd Duran placed 10th. -

Glee Reboot COLD OPEN – SCENE ONE FADE IN

glee reboot COLD OPEN – SCENE ONE FADE IN: INT. NETWORK NEWS DESK – ELECTION NIGHT GRAPHIC – “NOVEMBER 3, 2020- 6PM EST” (GERALDO RIVERA & KATIE COUIC ARE AT THE ANCHOR DESK) GERALDO I’m Geraldo Rivera along with Katie Couric. Tonight America decides who will run our country for the next 4 years! KATIE Will it be President Sue Sylvester (GRAPHIC – “SUE SYLVESTER PHOTO”) for the Republicans or will it Joe Biden (GRAPHIC – “JOE BIDEN PHOTO”) for the Democrats GERALDO America, this is how each candidate received their party’s nomination. KATIE (VO) (STOCK FOOTAGE OF JOE BIDEN AT THE DEMOCRATIC CONVENTION) After a rough start in the Primaries, former Vice President Biden easily coasted to victory after the first Super Tuesday. GERALDO While President Sue Sylvester took a non-traditional path for her rise to power. COLD OPEN – SCENE TWO INT. JOINT SESSION OF CONGRESS – JULY 4, 2020 (GRAPHIC - “JULY 4, 2020” (SUE WEARING HER VICE-PRESIDENT ATHLETIC JACKET STANDS AT THE PODIUM BEFORE A JOINT SESSION OF CONGRESS. THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE AND PRESIDENT PRO-TEM OF THE SENATE ARE BEHIND SUE) SUE SYLVESTER I stand before this joint session of Congress with a heavy weight on my shoulders. Like the time I had to carry an injured Chris Christie two miles after he was shot by Dick Cheney. I do have full support of the Cabinet and I implore Congress to invoke Amendment 25 – Section 4 of the United States Constitution. COLD OPEN – SCENE THREE INT. WHITE HOUSE - OVAL OFFICE – APRIL 5, 2020 (GRAPHIC – “APRIL 5, 2020) (SUE IS TALKING TO THE PRESIDENT) SUE SYLVESTER Mr. -

We Will Rock You”

“We Will Rock You” By Queen and Ben Elton At the Hippodrome Theatre through October 20 By Princess Appau WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS When one walks into the Hippodrome Theatre to view “We Will Rock You,” the common expectation is a compilation of classic rock and roll music held together by a simple plot. This jukebox musical, however, surpasses those expectations by entwining a powerful plot with clever updating of the original 2002 musical by Queen and Ben Elton. The playwright Elton has surrounded Queen’s songs with a plot that highlights the familiar conflict of our era: youths being sycophants to technology. This comic method is not only the key to the show’s success but also the antidote to any fear that the future could become this. The futuristic storyline is connected to many of Queen’s lyrics that foreshadow the youthful infatuation with technology and the monotonous lifestyle that results. This approach is emphasized by the use of a projector displaying programmed visuals of a futuristic setting throughout the show. The opening scene transitions into the Queen song “Radio Gaga,” which further affirms this theme. The scene includes a large projection of hundreds of youth, clones to the cast performing on stage. The human cast and virtual cast are clothed alike in identical white tops and shorts or skirts; they sing and dance in sublime unison, defining the setting of the show and foreshadowing the plot. Unlike most jukebox musicals the plot is not a biographical story of the performers whose music is featured. “We Will Rock You” is set 300 years in the future on the iPlanet when individuality and creativity are shunned and conformity reigns. -

Auction Journal Supplement

AUCTION JOURNAL SUPPLEMENT APRIL 29, 2011 HYATT REGENCY CENTURY PLAZA TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 2 Welcome to The Race to Erase MS Silent Auction! Our amazing items are displayed in the California Showroom on the California Level, two floors below the lobby of the Hyatt Regency Century Plaza. Page Item Live Auction 3 13 Travel 4 145-147 Fashion 5 250-253 That’s Entertainment 6 447-461 Jewels 8 543-547 Cuisine 9 637-643 Children’s Menagerie 10 717-718 Luxury 11 862-866 Art and Home Décor 12 925-929 Silent Auction Friday, April 29, 2011 6:30-8:30 pm Hyatt Regency Century Plaza Los Angeles, California The Silent Auction and our very special Live Auction include a unique collection of rare and extraordinary treasures. Countless volunteers have contributed their skill to develop this showcase with its vast array of gifts from generous donors throughout the world. Funds raised through the Auction will further critical research to find the cause and ultimate cure for the disease of multiple sclerosis. Therefore, we thank you from the bottom of our hearts for bidding generously and for helping all of those afflicted with MS enjoy a better today as well as strengthen their belief in a better tomorrow. LIVE Page 3 13. VIP Grammy Experience This ultimate VIP Grammy get-a-way experience includes 2 “Platinum” tickets for the 54th Annual Grammy Awards telecast at Staples Center in February 2012. Platinum level tickets are reserved for celebrities, sponsors and VIP guests – the only better seats in the house are those of the nominees and presenters themselves. -

2010 16Th Annual SAG AWARDS

CATEGORIA CINEMA Melhor ator JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) Melhor atriz SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) Melhor ator coadjuvante MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey – “UM OLHAR NO PARAÍSO” ("THE LOVELY BONES") (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) Melhor atriz coadjuvante PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) Melhor elenco AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. -

Spring 2017 • May 7, 2017 • 12 P.M

THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY 415TH COMMENCEMENT SPRING 2017 • MAY 7, 2017 • 12 P.M. • OHIO STADIUM Presiding Officer Commencement Address Conferring of Degrees in Course Michael V. Drake Abigail S. Wexner Colleges presented by President Bruce A. McPheron Student Speaker Executive Vice President and Provost Prelude—11:30 a.m. Gerard C. Basalla to 12 p.m. Class of 2017 Welcome to New Alumni The Ohio State University James E. Smith Wind Symphony Conferring of Senior Vice President of Alumni Relations Russel C. Mikkelson, Conductor Honorary Degrees President and CEO Recipients presented by The Ohio State University Alumni Association, Inc. Welcome Alex Shumate, Chair Javaune Adams-Gaston Board of Trustees Senior Vice President for Student Life Alma Mater—Carmen Ohio Charles F. Bolden Jr. Graduates and guests led by Doctor of Public Administration Processional Daina A. Robinson Abigail S. Wexner Oh! Come let’s sing Ohio’s praise, Doctor of Public Service National Anthem And songs to Alma Mater raise; Graduates and guests led by While our hearts rebounding thrill, Daina A. Robinson Conferring of Distinguished Class of 2017 Service Awards With joy which death alone can still. Recipients presented by Summer’s heat or winter’s cold, Invocation Alex Shumate The seasons pass, the years will roll; Imani Jones Lucy Shelton Caswell Time and change will surely show Manager How firm thy friendship—O-hi-o! Department of Chaplaincy and Clinical Richard S. Stoddard Pastoral Education Awarding of Diplomas Wexner Medical Center Excerpts from the commencement ceremony will be broadcast on WOSU-TV, Channel 34, on Monday, May 8, at 5:30 p.m. -

Glee: Uma Transmedia Storytelling E a Construção De Identidades Plurais

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA INSTITUTO DE HUMANIDADES, ARTES E CIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA MULTIDISCIPLINAR DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CULTURA E SOCIEDADE ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Salvador 2012 ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Dissertação apresentada ao Programa Multidisciplinar de Pós-graduação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de mestre em Cultura e Sociedade, área de concentração: Cultura e Identidade. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Djalma Thürler Salvador 2012 Sistema de Bibliotecas - UFBA Lima, Roberto Carlos Santana. Glee : uma Transmedia storytelling e a construção de identidades plurais / Roberto Carlos Santana Lima. - 2013. 107 f. Inclui anexos. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Djalma Thürler. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal da Bahia, Faculdade de Comunicação, Salvador, 2012. 1. Glee (Programa de televisão). 2. Televisão - Seriados - Estados Unidos. 3. Pluralismo cultural. 4. Identidade social. 5. Identidade de gênero. I. Thürler, Djalma. II. Universidade Federal da Bahia. Faculdade de Comunicação. III. Título. CDD - 791.4572 CDU - 791.233 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Dissertação aprovada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Cultura e Sociedade, Universidade Federal da Bahia, pela seguinte banca examinadora: Djalma Thürler – Orientador ------------------------------------------------------------- -

As Heard on TV

Hugvísindasvið As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Janúar 2013 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Kt.: 080288-3369 Leiðbeinandi: Pétur Knútsson Janúar 2013 3 Abstract In this paper I research four grammar variables by watching three seasons of American television programs, aired during the winter of 2010-2011: How I Met Your Mother, Glee, and Grey’s Anatomy. For background on the history of prescriptive grammar, I discuss the grammarian Robert Lowth and his views on the English language in the 18th century in relation to the status of the language today. Some of the rules he described have become obsolete or were even considered more of a stylistic choice during the writing and editing of his book, A Short Introduction to English Grammar, so reviewing and revising prescriptive grammar is something that should be done regularly. The goal of this paper is to discover the status of the variables ―to lay‖ versus ―to lie,‖ ―who‖ versus ―whom,‖ ―X and I‖ versus ―X and me,‖ and ―may‖ versus ―might‖ in contemporary popular media, and thereby discern the validity of the prescriptive rules in everyday language. Every instance of each variable in the three programs was documented and attempted to be determined as correct or incorrect based on various rules. Based on the numbers gathered, the usage of three of the variables still conforms to prescriptive rules for the most part, while the word ―whom‖ has almost entirely yielded to ―who‖ when the objective is called for. -

The Glee News

Inside:The Times of Glee Fox to end ‘Glee’? Kurt Hummel recieves great reviews on his The co-creator of Fox’s great acting, sining, and “Glee” has revealed dancing in his debut “Funny Girl” star Rachel Berry is photographed on the streets of New York plans to end the series, role of “Peter Pan”. walking five dogs. She will soon drop the news about her dog adoption Us Weekly reports. Ryan event. Murphy told reporters Wednesday in L.A. that the musical series will New meaning to “dog eats end its run next year after six seasons. The end of the show ap- dog” business pears to be linked to the Rising actors Berry and Hummel host Brod- death of Cory Monteith, one of its stars. Chris Colfer expands way themed dog show In the streets of New York, happy to be giving back. “After the emotional his talent from simple the three-legged dog to the Rachel uncertainly leads mother and her son. The three friends share a memorial episode for an actor and musician a dozen dogs on leads group hug, happily. Monteith and his char- to a screenplay wiriter through the street. Blaine Sam suggests to Mercedes acter Finn Hudson aired and Artie have positioned that they give McCo- “Old Dog New Tricks” is as well. last week, Murphy said themselves among some naughey to someone at the written by Chris Colfer, who it’s been very difficult to event, but Mercedes tells lunching papparazi, and claims his “two favorite move on with the show,” him to not bother - they’re loudly announce her arriv- cording things in life are animals the story reports. -

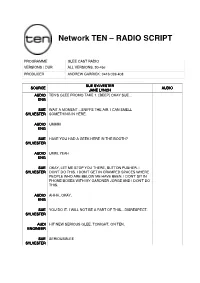

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT PROGRAMME GLEE CAST RADIO VERSIONS / DUR ALL VERSIONS. 30-45s PRODUCER ANDREW GARRICK: 0416 026 408 SUE SYLVESTER SOURCE AUDIO JANE LYNCH AUDIO TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] OKAY SUE… ENG SUE WAIT A MOMENT…SNIFFS THE AIR. I CAN SMELL SYLVESTER SOMETHING IN HERE. AUDIO UMMM ENG SUE HAVE YOU HAD A GEEK HERE IN THE BOOTH? SYLVESTER AUDIO UMM, YEAH ENG SUE OKAY, LET ME STOP YOU THERE, BUTTON PUSHER. I SYLVESTER DON'T DO THIS. I DON'T GET IN CRAMPED SPACES WHERE PEOPLE WHO ARE BELOW ME HAVE BEEN. I DON'T SIT IN PHONE BOXES WITH MY GARDNER JORGE AND I DON'T DO THIS. AUDIO AHHH..OKAY. ENG SUE YOU DO IT. I WILL NOT BE A PART OF THIS…DISRESPECT. SYLVESTER AUDI HIT NEW SERIOUS GLEE. TONIGHT, ON TEN. ENGINEER SUE SERIOUSGLEE SYLVESTER Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT FINN HUDSON SOURCE AUDIO CORY MONTEITH FEMALE TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. THANKS. HI AUSTRALIA, IT'S FINN HUSON HERE, HUDSON FROM TEN'S NEW SHOW GLEE. FEMALE IT'S REALLY GREAT, AND I CAN ONLY TELL YOU THAT IT'S FINN COOL TO BE A GLEEK. I'M A GLEEK, YOU SHOULD BE TOO. HUDSON FEMALE OKAY, THAT'S PRETTY GOOD FINN. CAN YOU MAYBE DO IT AUDIO WITH YOUR SHIRT OFF? ENG FINN WHAT? HUDSON FEMALE NOTHING. AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY… HUDSON FEMALE MAYBE JUST THE LAST LINE AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. UMM. GLEE – 730 TONIGHT, ON TEN. SERIOUSGLEE HUDSON FINN OKAY. -

{Download PDF} the Stars Are Right Ebook Free Download

THE STARS ARE RIGHT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Chaosium RPG Team | 180 pages | 14 May 2008 | CHAOSIUM INC | 9781568821771 | English | Hayward, United States The Stars are Right PDF Book Photo Courtesy: P! Natalie Dormer and Gene Tierney With HBO's massively successful fantasy series Game of Thrones finally over and a whole slew of spinoff series coming down the pipeline soon enough , many fans of the show are left wondering what star Natalie Dormer will do next. For instance, they've starred in the Ocean's film series and Burn After Reading. Here's What to Expect for the Super Bowl. It can't be denied that everyone knows her name. It can sometimes feel like society has hit a new level of boy craziness sometimes. Lea Michele and Naya Rivera The cast of Glee was riddled with as much in-house drama as a real-life glee club. When Lea Michele started gaining a massive fanbase, other characters started receiving fewer lines and less-important storylines. If more than one person in your household wants to vote, each person will need to create a personal ABC account. More than one person can use the same computer or device to vote, but each person needs to log out after voting. The achievement or service doesn't involve participation in aerial flight, and it can occur during engagement against a U. As such, it must be said that both these two stars deserve far more praise than they typically receive. As it turns out, the coffee business didn't quite work out. -

(PUGC), Princeton's Oldest and Most

FACTSHEET December 2012 The Princeton University Glee Club (PUGC), Princeton's oldest and most prestigious choir, was founded in 1874 by Andrew Fleming West '74, the first Dean of the Graduate College and continues to be the premier vocal ensemble at Princeton University. WHY IS IT CALLED A 'GLEE CLUB'? The name 'Glee Club' comes from 18th Century England – specifically from Harrow School (where the Glee Club's current director was educated!). The term referred then to a small group of men singing parlour songs, folk songs and other ditties in close harmony, normally without accompaniment. The early American Glee Clubs were based on this model but have since exploded in to the large ensembles we now find at many Ivy League schools. At Princeton we keep the name 'Glee Club' out of reverence for this tradition. WHO IS THE DIRECTOR? Gabriel Crouch has been the director of musical and choral performance at Princeton University and the director of the Princeton University Glee Club since 2010. Before his current post, Mr. Crouch was a member of the world renowned British vocal ensemble, the King’s Singers. In 2005, Mr. Crouch left the King’s Singers to accept the position as head of the choral program at DePauw University until joining the faculty at Princeton. Mr. Crouch holds a degree from the University of Cambridge where he completed a choral scholarship at Trinity College. HOW LARGE IS THE GLEE CLUB? The precise number of the Glee Club fluctuates from anywhere between 60 and 80 members. Currently, there are around 80 students who are current members of Glee Club as well as a piano accompanist who is also a student.