Corporations in the American Colonies Joseph S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4: the Colonies Grow, 1607-1770

The Colonies Grow 1607–1770 Why It Matters Independence was a spirit that became evident early in the history of the American people. The spirit of independence contributed to the birth of a new nation, one with a new government and a culture that was distinct from those of other countries. The Impact Today Americans continue to value independence. For example: • The right to practice one’s own religion freely is safeguarded. • Americans value the right to express themselves freely and to make their own laws. The American Republic to 1877 Video The chapter 4 video, “Middle Passage: Voyages of the Slave Trade,” examines the beginnings of the slave trade, focusing on the Middle Passage. 1676 • Bacon’s Rebellion c. 1570 • Iroquois Confederacy 1651 formed • First Navigation Act regulates colonial trade 1550 1600 1650 1603 1610 1644 • Tokugawa Shogunate • Galileo observes • Qing Dynasty emerges in Japan planets and stars established in with telescope China 98 CHAPTER 4 The Colonies Grow Compare-Contrast Study Foldable Make the following (Venn diagram) foldable to compare and contrast the peoples involved in the French and Indian War. Step 1 Fold a sheet of paper from side to side, leaving a 2-inch tab uncovered along the side. Fold it so the left edge lies 2 inches from the right edge. Step 2 Turn the paper and fold into thirds. Step 3 Unfold and cut along the two inside fold lines. Cut along the two folds on the front flap to make 3 tabs. Step 4 Label the foldable as shown. The French and Indian War French British and Native Both and Americans Colonists The South Side of St. -

Massachusetts Bay Colony

Massachusetts Bay Colony (Edited from Wikipedia) The Massachusetts Bay Colony was an English settlement on the east coast of North America (Massachusetts Bay) in the 17th century. The settlement was located in New England, situated around the present-day cities of Salem and Boston. The territory administered by the colony included much of present-day central New England, including portions of the U.S. states of Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. Territory claimed but never administered by the colonial government extended as far west as the Pacific Ocean. The colony was founded by the owners of the Massachusetts Bay Company, which included investors in the failed Dorchester Company, which had in 1623 established a short-lived settlement on Cape Ann. The Massachusetts Bay Colony, begun in 1628, was the company's second attempt at colonization. The colony was successful, with about 20,000 people migrating to New England in the 1630s. The population was strongly Puritan, and its governance was dominated by a small group of leaders who were strongly influenced by Puritan religious leaders. Although its governors were elected, the electorate were limited to freemen, who had been examined for their religious views and formally admitted to the local church. As a consequence, the colonial leadership exhibited intolerance to other religious views, including Anglican, Quaker, and Baptist theologies. Although the colonists initially had decent relationships with the local native populations, frictions arose over cultural differences, which were further exacerbated by Dutch colonial expansion. These led first to the Pequot War (1636–1638), and then to King Philip's War (1675–1678), after which most of the natives in southern New England had been pacified, killed, or driven away. -

Chapter 2 Critique of Puritan New England

Critique of the American Institution of Education Richard B. Wells © 2013 Chapter 2 Critique of Puritan New England § 1. The Incubation Period of American Civilization What I am calling the incubation period is the nearly one and one-half centuries from the establishment of Jamestown in 1607 until 1750, just after the end of King George's War (1744-8). This is the period in history telling the story of what became the United States of America from the evolution of divers British colonial enterprises into a distinctly different North American civilization. Meaning no disrespect to the people of the also-American nations of Canada and Latin America, I am going to call this 'the' American civilization because I have to call it something and because when "America" is referred to today in most countries what is most often meant by this reference is the USA (judging from my experiences of being called an "American" by people from every continent except central and South America, whose people have tended to call me either a "yanqui" or a "norteamericano," and Australia, whose people have tended to call me a "Yank"; real Yankees, however, laconically inform me I am not one of them). The date 1750 is somewhat arbitrarily chosen. A number of historians have seemed to favor the year 1763 to mark the historical epoch, apparently on the basis of, as Morison and Commager put it, "it was not until 1763 that the Thirteen Colonies began to strain at their imperial leash." In point of fact crisp dates marking historical epochs are rarely justifiable by actual events. -

Pre-Colonial “Summer Stuff” Christopher Columbus (1492

Pre-Colonial “Summer Stuff” Christopher Columbus (1492): • Italian-born navigator who found fame when he landed in the Americas (October 12, 1492) • Left Spain with three ships (Nina, Pinta, Santa Maria) • He sailed west across the Atlantic Ocean to find a water route to Asia (was convinced the Americas were an extension of China) • Returned from his expedition with gold, encouraging future exploration and the Columbian Exchange Amerigo Vespucci (1454-1512): • Italian member of a Portuguese expedition who explored South America • Discovery suggested that the expedition had found a “New World” Treaty of Tordesillas (1493): • Treaty made by the Pope between Spain and Portugal • Created an imaginary Line of Demarcation to divide the New World • East of the line went to Portugal; west of the line went to Spain • The line would later affect colonization in Africa and Asia “New Spain” (1400s and 1500s): • Spain’s tightly controlled empire in the New World • Spaniards developed the encomienda system, using Native Americans as their forced form of labor • With the death of Native Americans, Spaniards began importing African slaves to supply their labor needs St. Augustine, Florida (1598): • French Protestants (Huguenots) went to the New World to freely practice their religion; they formed a colony near modern-day St. Augustine, Florida • Spain, which oversaw Florida, reacted violently to the Huguenots, because they were trespassers and because they were viewed as heretics by the Catholic Church • Spain sent a force to the settlement and massacred -

Register of the Colonial Dames of America 1893

RegisteroftheConnecticutSocietyColonialDamesAmerica,1893-1907 NationalSocietyoftheColonialDamesAmericainStateConnecticut REGISTERF O THE CONNECTICUT SOCIETYF O THE COLONIAL DAMESF O AMERICA Register o f The Society of the Colonial Dames of America F1VE H UNDRED COP1ES PR1NTED SKo.„Z.Z. v-. ^@— - ^__g)> Tfiggi/terqfthe t ' oi?r?ecticut <£ocietvofthe < o/onial* , * ^yH^r-U^Ly / FOUNDERS O f The Connecticut Society of the Colonial Dames of America. *•'?/* - r/..: ..t s& lC®amtfofJ$mert£.a > * §&&* £Mijh<dhythe GomwcHcutefbcieiy Us 2 £>oy./2tko &A3VARD C OLLEGE IIP***< |Y EXCHVNSE PUBLICATION C OMMITTEE Mrs. J ohn M. Holcombe, Chairman Miss M ary K. Talcott Mrs. F ranklin G. Whitmore Miss M ary E. Beach Mrs. C harles A. White Mrs. W nxiSTON Walker Mrs. A rthur Perkins . Mrs. C harles E. Gross MMT^tS, m m. CONTENTS Incorporators, 9 Actf o Incorporation 11 Constitution, 1 3 National O fficers, 19o7 23 Officers a nd Managers of the Connecticut Society of Colonial D ames 25 Former O fficers and Managers, 28 Introduction, 3 3 fRolls o Membership, 41 In M emoriam, 195 Eligibility L ist .198 Ministers o f Parishes, 2oo Preachers o f Election Sermons 2o1 Patentees o f the Charter 2o3 Signatures o f the Members of the General Court of April, 1639 [ From Colonial Records of Connecticut, I, 227], . 2o4 Also S ignatures of Fifteen Members of the General Court of 1 665 2o5 Explanatory N otes 2o8 Quotation f rom Sermon of Rev. Mr. Stoughton of Dor chester, 1668, 2o6 The N aming of New London, 1658, 2o6 Ancestors a nd Descendants, . 2o9 Indexf o Members, 321 LISTF O ILLUSTRATIONS Portraits o f the Founders Frontispiece The W yllys House, 33 Mabel H arlakenden 36 Rev. -

Print › Unit 3-The Early English Settlements, the Colonies, And

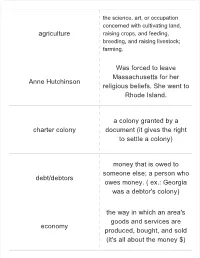

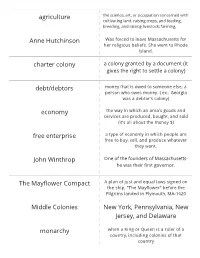

the science, art, or occupation concerned with cultivating land, agriculture raising crops, and feeding, breeding, and raising livestock; farming. Was forced to leave Massachusetts for her Anne Hutchinson religious beliefs. She went to Rhode Island. a colony granted by a charter colony document (it gives the right to settle a colony) money that is owed to someone else; a person who debt/debtors owes money. ( ex.: Georgia was a debtor's colony) the way in which an area's goods and services are economy produced, bought, and sold (it's all about the money $) a type of economy in which people are free to buy, sell, free enterprise and produce whatever they want. One of the founders of John Winthrop Massachusetts-he was their first governor. A plan of just and equal laws signed on the ship, "The The Mayflower Compact Mayflower" before the Pilgrims landed in Plymouth, MA-1620 New York, Pennsylvania, Middle Colonies New Jersey, and Delaware when a King or Queen is a monarchy ruler of a country, including colonies of that country Massachusetts, Rhode New England Colonies Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire a type of democratic government-It's the closest to New England Town the people, it involves the Meetings largest number of people, it's the most open. Came to Plymouth, Massachusetts on "The Mayflower" Pilgrims They were a type of Puritans that wanted to separate from the English Church. Plymouth, Massachusetts A town started by the (Bay Colony) Pilgrims in 1620. privately owned and proprietary colony operated for profit Was founded for religious Providence, Rhode Island freedom by Roger Williams. -

Topic of Discussion – Early Representative Governments

Discussion 3-2 US History ~ Chapter 3 Topic Discussions E Lundberg Topic of Discussion – Early Representative Governments Related Topics Chapter Information ~ Ch 3; 4 sections; 29 pages Great Indian Law of the Iroquois The English Establish 13 Colonies (1585-1732) Section 1 ~ Early Colonies Have Mixed Success Pages 60-65 The Magna Carta Section 2 ~ New England Colonies Pages 66-75 English Colonial Government Section 3 ~ The Southern Colonies Pages 76-81 Section 4 ~ The Middle Colonies Pages 82-85 The Enlightment Key Ideas Key Connections - 10 Major (Common) Themes 1. How cultures change through the blending of different ethnic groups. 2. Taking the land. What influences did the English government have 3. The individual versus the state. 4. The quest for equity - slavery and it’s end, women’s suffrage etc. the colonists form of representative government? 5. Sectionalism. 6. Immigration and Americanization. What influence did the Native Americans have in 7. The change in social class. 8. Technology developments and the environment. the colonists form of representative government? 9. Relations with other nations. 10. Historiography, how we know things. Talking Points I Introduction As defined a colony is a group of people who leave their native country to form a community in a new land. The harsh reality is, there are many realities that need to be worked out prior to people leaving their homeland: A. Shelter B. Food source C. Protection “Who” is going to do “what” in the community? Who is management and who is the work force? So the issue at hand is, how does the community get along? There has to be some set of rules or guidelines to follow. -

Register of the National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New

THE C OLONIAL DAMES OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK NEv. Y ORK PUBLIC LldRARY , A .vm , Lenox jaiid Til9«n Fiiuin|ati*n$. REGISTER O F THE ^COLONIAL DAMES HEOF T STATE OF NEW YORK 1893-1901 ORGANIZED A PRIL 29th, 1893 INCORPORATED APRIL 29th, 1893 PUBLISHED B Y THE AUTHORITY OF THE BOARD OF MANAGERS NEWYORK M CM1 CERTIFICATE O F INCORPORATION CERTIFICATE O F INCORPORATION OFHE T Colonial D ames of the State of New York We, t he undersigned women, citizens of the United States and of the State of New York, all being of full age, do hereby associate and form ourselves into a Society by the name, style and title of: "The C olon1al Dames of the State of New York/' andn i order that the said Society shall be a body corporate and politic under and in pursuance of the Act of the Legislature of the State of New York (Chapter 267), passed May 12, 1875, entitled "An Act for the incorporation of societies or clubs for certain lawful purposes," and of the several Acts of the Legis lature of said State amendatory thereof, we do hereby certify: F1rst. — T hat the name or title by which the said Society shall be known in law, shall be "The Colonial Dames of the State of New York." Second. — T hat the particular business and objects of the said Society shall be patriotic, historical, literary, benevolent and so cial, and for the purposes of perpetuating the memory of those honored men whose sacrifices and labors, in colonial times and until national independence was assured, potentially aided in lay ing the foundations of a great empire ; of collecting and -

The New England Colonies in the 17Th Century

The New England Colonies in the 17th Century Pilgrims arrive in Harvard College founded Plymouth King Philip’s War 1620 1629 1636 1644 1675 1692 Puritans found Rhode Island Salem Witch Massachusetts Bay founded Trials Units 1.3 The New England Colonies Theme #1: Seventeenth-century New England was characterized by a homogeneous society that revolved largely around Puritanism and its stern ideal of perfectionism. The New England colonies contained a healthy population with long life spans, a strong family structure, tightly-knit towns and congregations, and a diversity of economic activities. What political and religious circumstances in England led to the formation and development of New England? I. Protestant Reformation (1517) A. Martin Luther: breaks with Catholic church B. John Calvin: Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536) 1. Elaborated on Luther’s ideas 2. God was all-powerful, all-knowing, all-good 3. Humans were weak and wicked due to original sin 4. Predestination a. “The elect” b. “visible saints”– conversion experience c. Refuted “Good works” philosophy of the Catholic Church C. Church of England 1. King Henry VIII broke with the Roman Catholic Church in 1534 -- Leader of the Church of England (Anglican Church) 2. Puritans: sought to reform the church 3. Separatists (later, Pilgrims) sought to leave the Anglican Church permanently 4. King James I was threatened by the Separatist challenge and persecuted them II. Pilgrims A. First wave of Separatists 1. Separatists left England for Holland -- Led by Rev. John Robinson 2. Separatists later left Holland for America in 1620 3. Mayflower, 1620 4. Plymouth Bay The Rev. -

A New Nation Struggles to Find Its Footing: Power Struggles, 1789-1804

Jamestown settlement The Great Migration, 1620-1640 Settled in 1607 (modern day Virginia) Early Colonial America With the European religious/political climate The first successful English settlement in America Settlement to 1764 (page 1 of 2) so hostile and threatening, many of Calvinist, Financed and coordinated by the Virginia Puritan and of nonconformist beliefs left. Company of London. Some of the migration was from expatriate Georgia Colony Why? The company expected to make money English communities in the Netherlands of James Oglethorpe, an 18th century British member in this investment; settlers were supposed to nonconformists and Separatists who had set of Parliament, established Georgia as a common repay the company with interest over 7 years. up churches there since the 1590s solution for two problems: 1630-1640, about 20,000 came to colonies. Tension between Spain and Great Britain was “Lost Colony” at Roanoke Island The Great Migration is not so named because high, and the British feared that Spanish Florida Settled in 1585 (modern day North Carolina), by of sheer numbers, which were much less than would threaten the British Carolinas. 1587 all 90 settlers had disappeared. the number of English citizens who emigrated He established a colony in the contested border First birth to European parents on American soil: elsewhere during this time. The distinction region of Georgia and populated it with debtors Virginia Dare, born 18th August 1587 drawn is that the movement of colonists to who would otherwise have been imprisoned New England was not predominantly male, according to standard British practice. New Amsterdam settlement was a Dutch colony but of families with some education, leading This plan would both rid Great Britain of its settled in 1609 (it is now New York City) relatively prosperous lives. -

Transcript of Lecture Delivered by Richard S. Dunn, Ph D. on September 12, 1998 John Winthrop, Jr., of Connecticut, the First Govenor of the East End

Transcript of Lecture Delivered By Richard S. Dunn, Ph D. on September 12, 1998 John Winthrop, Jr., of Connecticut, The First Govenor of the East End If the man I’m going to tell you about this afternoon had had his way 325 years ago, East Hampton would now be a town in the state of Connecticut rather than in New York. Whether that would have been a good thing or a bad thing, I leave to you. But John Winthrop, Jr’s repeated efforts to annex the East End of Long Island to Connecticut are well worth examining. Obviously he failed. But the East Enders in the1650s, 1660s, and 1670s wanted him to succeed. And the struggle that he led for about twenty years for control of eastern Long Island reveals a lot about the political situation in English America at that time. John Winthrop, Jr. was one of the most attractive, intelligent, and interesting men in seventeenth-century New England. He has always been overshadowed by his famous father, John Winthrop (who was governor of Massachusetts from 1630 to 1649), and indeed the father was a more creative and influential leader than the son. But John Winthrop, Jr. was a highly creative and influential leader in his own right. He was born in England in 1606, came to America one year after his father in 1631, and had a strikingly diversified career until he died in 1676. Winthrop was good at many different things. He was the premier scientist in early America, and a founding member of the Royal Society in England. -

Quizlet Flashcards Unit 3.Pdf

agriculture the science, art, or occupation concerned with cultivating land, raising crops, and feeding, breeding, and raising livestock; farming. Anne Hutchinson Was forced to leave Massachusetts for her religious beliefs. She went to Rhode Island. charter colony a colony granted by a document (it gives the right to settle a colony) debt/debtors money that is owed to someone else; a person who owes money. ( ex.: Georgia was a debtor's colony) economy the way in which an area's goods and services are produced, bought, and sold (it's all about the money $) free enterprise a type of economy in which people are free to buy, sell, and produce whatever they want. John Winthrop One of the founders of Massachusetts- he was their first governor. The Mayflower Compact A plan of just and equal laws signed on the ship, "The Mayflower" before the Pilgrims landed in Plymouth, MA-1620 Middle Colonies New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware monarchy when a King or Queen is a ruler of a country, including colonies of that country New England Colonies Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire New England Town Meetings a type of democratic government-It's the closest to the people, it involves the largest number of people, it's the most open. Came to Plymouth, Massachusetts on "The Pilgrims Mayflower" They were a type of Puritans that wanted to separate from the English Church. Plymouth, Massachusetts A town started by the (Bay Colony) Pilgrims in 1620. proprietary colony privately owned and operated for profit Providence, Rhode Island Was founded for religious freedom by Roger Williams.