History from Police Archives Two Teaching Packagesfrom the Open University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

90203NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. I." :-:')'," , ~c">"'" ill' .. "J! . l' 0, • ~l ! 1 o ,~ ..~ . .;I' ,.}/" 'v {f. REPORT OF THE CHIEF CONSTABLE OF THE '\ WEST MIDLANDS POLICE ,j FOR THE J I YEAR 1982 U.S. Department of Justice 90203 National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or orgamzation originating It. Pomts of vIew or opimons stated in this document are tho..le of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official posltJon or polIcies of the National Institute of JustIce. Chief Constable's Office PermIssion to reproduce this COPYrighted material has been Lloyd House granted by Colmore Circus Queensway --tio...r:J:humhria .-l?o...l.J..ce-__ ~. __ Birmingham 84 6NQ He adquar_t e r S ___ 'h._____ _ to the National Criminal Justice Reference SelVice (NCJRS). Further reproduction outSide of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the cOPYright owner. r WEST MIDLANDS POLICE I. MEMBERS OF THE POLICE AUTHORITY Chairman: Councillor E T Shore (Birmingham, SaZtley) I ; Vice-Chairman: ·Co~ncillor T J Savage (Birmingham, Erdington) Local Authority Representatives Magistrate Members Ward Councillor D M Ablett (Dudley, No. 6) J D Baker Esq JP FCA Councillor D Benny JP (Birmingham, Sandwell) K H Barker Esq Councillor E I Bentley (MerideiYl, No.1) OBE DL JP FRIeS Councillor D Fysh (Wolverhampton. No.4) Captain. J E Heydon Councillor J Hunte (Birmingbam, Handsworth) ERD JP Councillor K RIson (Stourbridge, No.1) S B Jackson EsqJP FCA Councillor -

Eli Whalley's Donkey Stones

71 June 2013 Issue THE NEWSLETTER OF THE SOCIAL HISTORY CURATORS GROUP Experimental Re-interpretation & Display Community Engagement at Birmingham Eli Whalley’s Donkey Stones Medical Objects Part II Join SHCG? If you’re reading this and you’re Welcome to Issue 71 not a member of SHCG but would like to join please contact: At the end of June Laura Briggs a new permanent Membership Secretary exhibition opens at Email: [email protected] Newcastle’s Theatre Royal, in which the history of Write an article for theatre is charted SHCG News? from its origins in You can write an article for the News Ancient Greece to on any subject that you feel would be the present day. An interesting to the museum community. important part of Project write ups, book reviews, object the narrative studies, papers given and so on. We focuses on the welcome a wide variety of articles medieval mystery Model of Noah's ark relating to social history and museums. plays, in which Image courtesy of Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums DEADLINE FOR NEXT ISSUE: stories from the 18 October 2013 Bible were acted out. Among the best known of the mystery plays was the story of Noah and SHCG NEWS will encourage the Flood. To help illustrate this in the Theatre Royal exhibition a model ark and publish a wide range of views from was sought, and Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums were happy to help as those connected with history and we have, would you believe, not one but two models of Noah’s handiwork. museums. -

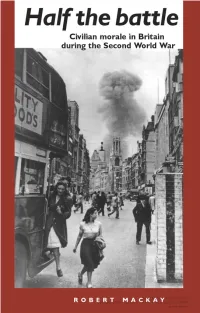

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM Via Free Access HALF the BATTLE

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access HALF THE BATTLE Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 1 16/09/02, 09:21 Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 2 16/09/02, 09:21 HALF THE BATTLE Civilian morale in Britain during the Second World War ROBERT MACKAY Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 3 16/09/02, 09:21 Copyright © Robert Mackay 2002 The right of Robert Mackay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 5893 7 hardback 0 7190 5894 5 paperback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs. -

BIOLOGY 639 SCIENCE ONLINE the Unexpected Brains Behind Blood Vessel Growth 641 THIS WEEK in SCIENCE 668 U.K

4 February 2005 Vol. 307 No. 5710 Pages 629–796 $10 07%.'+%#%+& 2416'+0(70%6+10 37#06+6#6+8' 51(69#4' #/2.+(+%#6+10 %'..$+1.1); %.10+0) /+%41#44#;5 #0#.;5+5 #0#.;5+5 2%4 51.76+105 Finish first with a superior species. 50% faster real-time results with FullVelocity™ QPCR Kits! Our FullVelocity™ master mixes use a novel enzyme species to deliver Superior Performance vs. Taq -Based Reagents FullVelocity™ Taq -Based real-time results faster than conventional reagents. With a simple change Reagent Kits Reagent Kits Enzyme species High-speed Thermus to the thermal profile on your existing real-time PCR system, the archaeal Fast time to results FullVelocity technology provides you high-speed amplification without Enzyme thermostability dUTP incorporation requiring any special equipment or re-optimization. SYBR® Green tolerance Price per reaction $$$ • Fast, economical • Efficient, specific and • Probe and SYBR® results sensitive Green chemistries Need More Information? Give Us A Call: Ask Us About These Great Products: Stratagene USA and Canada Stratagene Europe FullVelocity™ QPCR Master Mix* 600561 Order: (800) 424-5444 x3 Order: 00800-7000-7000 FullVelocity™ QRT-PCR Master Mix* 600562 Technical Services: (800) 894-1304 Technical Services: 00800-7400-7400 FullVelocity™ SYBR® Green QPCR Master Mix 600581 FullVelocity™ SYBR® Green QRT-PCR Master Mix 600582 Stratagene Japan K.K. *U.S. Patent Nos. 6,528,254, 6,548,250, and patents pending. Order: 03-5159-2060 Purchase of these products is accompanied by a license to use them in the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Technical Services: 03-5159-2070 process in conjunction with a thermal cycler whose use in the automated performance of the PCR process is YYYUVTCVCIGPGEQO covered by the up-front license fee, either by payment to Applied Biosystems or as purchased, i.e., an authorized thermal cycler. -

Governance and Urban Development in Birmingham: England's Second

Governance and urban development in Birmingham England’s second city since the millennium Acknowledgements This report was written by Liam O’Farrell, Research Associate at the University of Birmingham with funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation as part of the “Democratic Foundations of the Just City” project, which was a comparative study of housing, urban planning and governance in three European second cities: Birmingham, Lyon and Zurich. The project was a collaboration between the University of Zurich’s Centre for Democracy Studies Aarau (ZDA) and the University of Birmingham’s Centre for Urban and Regional Studies (CURS). The report was made possible through the support of a number of colleagues, including Dr Peter Lee at the University of Birmingham’s CURS; Dr Eric Chu, previously at CURS and now at the University of California, Davis; Oliver Dlabac and Roman Zwicky at the University of Zurich’s ZDA; and Dr Charlotte Hoole at the University of Birmingham’s City-REDI. Unless otherwise cited, photographs in this report were provided by Roman Zwicky, part of the research team. Birmingham analysis maps were produced by Dr Charlotte Hoole using publicly available ONS datasets. We would like to thank those working in the housing sector across the city who generously shared their knowledge and experience of planning and development in Birmingham. The “Democratic Foundations of the Just City” project was supported by: • The Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), by means of a research grant for the project “The Democratic Foundations of the Just City” (100012M_170240) within the International Co-Investigator Scheme in cooperation with the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) in the UK. -

The Edinburgh Gazette, January 7, 3938

THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, JANUARY 7, 3938. Air Ministry, FOB DISTINGUISHED SEBVICE. 1st January 1938. Police: England and Wales. PEINCBSS MAEY'S EOYAL AIE FOECE George Campbell Vaughan, Chief Constable, NUESING SEEVIGE. West Biding of Yorkshire Constabulary. Captain Athelstan Popkess, Chief Constable, The KING has been graciously pleased to Nottingham City Police Force. approve of the award of the-Boyal Eed Cross Thomas Alfred Burrows, Chief Constable, (Second Class) to the undermentioned member Beading Borough Police Force. of Princess Mary's Eoyal Air Force Nursing Bobert Gardiner, M.B.E., Assistant Chief Con- Service in recognition of special devotion and stable, Durham Constabulary. competency displayed by her in the nursing John Eichard Dodd, M.B.E., Assistant Chief and care of the sick in Eoyal Air Force Constable, Cheshire Constabulary. Hospitals at Home and Abroad:— Edward Percy Bell, Chief Superintendent and Senior Sister, Miss Grace Elsie Margaret Deputy Chief Constable, Newcastle-upon- Olubb. Tyne City Police Force. James Booth, M.B.E., Chief Superintendent, City of London Police Force. William Taylor, Superintendent, Northumber- land Constabulary. Whitehall, January I, 1938. His Majesty The KING has been graciously pleased to award the King's Police Medal to the Police: Isle of Man. Officers of Police and Fire Brigades whose Charles Joshua Faragher, Chief Inspector. names appear below:— Police: Scotland. FOB GALLANTRY. William Patrick Chambers, Superintendent, Midlothian Constabulary. Police: England and Wales. George Gray, Superintendent, Eenfrew Constabulary. Cecil Frank Cavalier, Constable, Metropolitan Police Force. Police: Northern Ireland. John William Chesterman, Constable, Metro- Bobert Browne, Head Constable, Boyal Ulster politan Police Force. Constabulary. Edward Ernest Freeland, Constable, Metro- Fitre Brigades: England and Wales. -

Tauber Chronology – Last Revised: May 2021

Richard Tauber (1891-1948) An illustrated Chronology Updated, with new features and expanded Picture Gallery Daniel O’Hara With a Foreword and Afterword by Dr. Nicky Losseff and Marco Rosenkranz May 2021 Saltburn-by-the-Sea Daniel O’Hara – Richard Tauber Chronology – Last revised: May 2021 Dedication Dedicated to the memory of Richard Tauber Born: Linz, 16 May 1891. Died: London, 8 January 1948, and of John Marsom [1940-2018], my loving partner for over 46 years. Warning: Earlier versions of this work have been archived and pirated by other websites. The most recent update will always be the one found here: http://www.richard-tauber.de/ What’s New in this Edition? A new feature, I thought it might be helpful briefly to mention at the beginning entries that are new – or significantly changed - in this edition, so readers already familiar with the previous edition(s) can go straight to the relevant pages. ● The UK tour in April 1937 began in Dublin: new dates/venues/details have been added. Additional details of his visits to Ireland in April 1935 and Jan 1945 have also been confirmed. ● A new work has been added to the list of RT’s stage appearances. Morgen wider Lustik!, an operetta by Heinz Lewin (1888-1942), a boyhood friend of Tauber’s in Wiesbaden, who perished in the Holocaust, was performed at the Theater des Westens in Berlin in 1921/2. I thank Heinz Lewin’s granddaughter, Yvonne Mocatta, for this information. ● New photographs have been added, including two of Tauber’s grave, one attended by the youthful author, taken in March 1978. -

105171NCJRS.Pdf

------ ~ If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. CR--~-r < r /~d-1-rl foJr~1 ~r'.·.:·':·, ".~,'."""., ,; ..... I • ,,_',~ ." ,'" ~ I ( • . :-. \ • ., ,), .' 0 ~. \ , , ,,; . ~~J~';:"<~~ ~.'_ ",~ ~',~' , '.' ' ~ ~..: ~ .~;. ., f Report of the iL.••. ··.. L.·. T'1 of 105171 U.S. Department of Justice Nationallnstltule of Justice This document has been reproduced exaclly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policie .. of the National Institute of J'Jstice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted by Chief Constable West Midlands Police to the National Criminal JUstice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the copyright owner. v' Report of ---I the CHIEF CONSTABLE of WEST MIDLANeS POLICE '1986 ! Members of the Police Authority Chairman: Councillor P R Richards Vice Chairman: Co un cillo, E .:; Carless Local Authority Representatives BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL Councillor M Afzai BSc SAT Councillor S Austin Councillor H C Blumenthal Councillor N A Bosworth CBE LLB Councillor F W Carter Councillor Mrs S Hunte Councillor L Jones Councillor G Khan Councillor R A Wootton COVENTRY CITY COUNCIL Councillor H Richards Councillor P W G Robinson Councillor T W Sawdon BSc FBOA FSMC JP DUDLEY METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL Councillor D M Ablett Councillor J A H Edmonds OBE MIMI Vacant -

British Strategic Bombing Benjamin Joyner Benjamin Joyner, From

142 Joyner British Strategic Bombing Ironically, Britain would soon pass through the crucible of modern strategic bombing herself. Benjamin Joyner British experience in the Blitz Benjamin Joyner, from Equality, Illinois, earned his BA in History in 2010 with a The German strategic bombing campaign against the British was the first minor in Political Science. The former homeschooler is entering graduate school in massive application of Douhet’s ideas in a modern war involving western fall 2010 to pursue a MA in History. This paper was written as a sophomore in nations. The “Battle of Britain” lasted from July 10th 1940 through fall 2008 for HIS 3420 (World War II) for Dr. Anita Shelton. December 31st of the same year. The first part of this massive bombardment focused on destroying the RAF, but on September 9th the focus shifted to _____________________________________________________________ major cities and urban centers. The goal of the Germans was to remove the British from the war by breaking the civilian will to fight. This change in targets and objectives came to be known as the Blitz. During this time The British strategic bombing campaigns against Germany during the English cities such as Belfast, Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Clydebank, Second World War have been a topic of much discussion and debate over Coventry, Greenock, Sheffield, Swansea, Liverpool, Hull, Manchester, the years. Initially seen as a way to minimize the loss of Allied lives while Portsmouth, Plymouth, Nottingham and Southampton were all targeted by putting great pressure on the Germans, some historians see the British the Luftwaffe and suffered heavy casualties. -

US Military Casualties

U.S. Military Casualties - Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) Names of Fallen (As of May 22, 2015) Service Component Name (Last, First M) Rank Pay Grade Date of Death Age Gender Home of Record Home of Record Home of Record Home of Record Unit Incident Casualty Casualty Country City of Loss (yyyy/mm/dd) City County State Country Geographic Geographic Code Code ARMY ACTIVE DUTY AAMOT, AARON SETH SPC E04 2009/11/05 22 MALE CUSTER WA US COMPANY C, 1ST BATTALION, 17TH INFANTRY AF AF AFGHANISTAN JELEWAR REGIMENT, 5 SBCT, 2 ID, FORT LEWIS, WA ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ABAD, SERGIO SAGONI SPC E03 2008/07/13 21 MALE MORGANFIELD UNION KY US COMPANY C, 2ND BATTALION, 503RD INFANTRY AF AF AFGHANISTAN FOB FENTY REGIMENT, CAMP EDERLE, ITALY MARINE ACTIVE DUTY ABBATE, MATTHEW THOMAS SGT E05 2010/12/02 26 MALE HONOLULU HONOLULU HI US 3D BN 5TH MAR, (RCT-2, I MEF FWD), 1ST MAR DIV, CAMP AF AF AFGHANISTAN HELMAND CORPS PENDLETON, CA PROVINCE ARMY NATIONAL ABEYTA, CHRISTOPHER PAUL SGT E05 2009/03/15 23 MALE MIDLOTHIAN COOK IL US COMPANY D, 1ST BATTALION, 178TH INFANTRY, AF AF AFGHANISTAN JALALABAD FST GUARD WOODSTOCK, IL ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ACEVES, OMAR SSG E05 2011/01/12 30 MALE EL PASO EL PASO TX US 693D ENGINEER COMPANY, 7TH EN BN, 10TH AF AF AFGHANISTAN GELAN, GHAZNI SUSTAINMENT BDE, FORT DRUM, NY PROVINCE ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ACOSTA, EDWARD JOSEPH SPC E04 2012/03/05 21 MALE HESPERIA SAN CA US USA MEDDAC WARRIOR TRANSITION CO, BALBOA NAVAL AF US UNITED STATES SAN DIEGO BERNARDINO MEDICAL CENTER, SAN DIEGO, CA 92134 ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ACOSTA, RUDY ALEXANDER SPC E03 2011/03/19 -

PM Pledges to Recruit 20,000 Officers

federationWest Midlands Police Federation August/September 2019 PM pledges to recruit 20,000 officers www.polfed.org/westmids Fixed Fee Divorce West Midlands Police + VAT* Divorce and Children Law Specialists FREE£350 first appointment McAlister Family Law is the country’s leading provider of police divorce and family services. Whether you are facing divorce and are worried about the impact on your pension or are seeking contact with your children or any other family law dispute, we are here to help. • Leaders in police divorce and children cases. • Over 20 years’ experience in representing police officers facing divorce and children disputes. • Experts in police pensions and divorce. • Fixed fees and discounted rates for police officers and personnel. *Conditions apply. See website for details. McAlister Family Law. Chris Fairhurst 2nd Floor, Commercial Wharf, 6 Commercial Street, Manchester M15 4PZ Partner www.mcalisterfamilylaw.co.uk 0333 202 6433 MFL A4 Police Divorce Advert.indd 1 15/11/2018 15:07 Welcome What’s inside Welcome to the August/September 2019 edition of federation - the 04 Secretary’s introduction 16 Reasonable Adjustment magazine for members of West 05 Home Office backs 2.5 per cent Passports: supporting a diverse Midlands Police Federation. workforce We are always on the look-out for police pay rise good news stories so please get in 05 Police covenant touch if you have something to share with colleagues. It does not have to 06 Latest developments on 18 relate to your policing role – though pensions we are definitely interested in hearing about what’s going on around the 07 Federation agrees collective Force.