Exploring America's Musical Identity: a Comparison Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 20, 2008 2655Th Concert

For the convenience of concertgoers the Garden Cafe remains open until 6:oo pm. The use of cameras or recording equipment during the performance is not allowed. Please be sure that cell phones, pagers, and other electronic devices are turned off. Please note that late entry or reentry of The Sixty-sixth Season of the West Building after 6:30 pm is not permitted. The William Nelson Cromwell and F. Lammot Belin Concerts National Gallery of Art 2,655th Concert Music Department National Gallery of Art Jeni Slotchiver, pianist Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue nw Washington, DC Mailing address 2000b South Club Drive January 20, 2008 Landover, md 20785 Sunday Evening, 6:30 pm West Building, West Garden Court www.nga.gov Admission free Program Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) Bachianas brasileiras no. 4 (1930-1941) Preludio (Introdu^ao) (Prelude: Introduction) Coral (Canto do sertao) (Chorale: Song of the Jungle) Aria (Cantiga) (Aria: Song) Dansa (Miudinho) (Dance: Samba Step) Francisco Mignone (1897-1986) Sonatina no. 4 (1949) Allegretto Allegro con umore Carlos Guastavino (1912-2000) Las Ninas (The Girls) (1951) Bailecito (Dance) (1941) Gato (Cat) (1940) Camargo Guarnieri (1907-1993) Dansa negra (1948) Frutuoso de Lima Viana (1896-1976) Coiia-Jaca (Brazilian Folk Dance) (1932) INTERMISSION Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924) The Musician Indian Diary: Book One (Four Studies on Motifs of the Native American Indians) (1915) Pianist Jeni Slotchiver began her formal musical studies at an early age. A He-Hea Katzina Song (Hopi) recipient of several scholarships, she attended the Interlochen Arts Academy Song of Victory (Cheyenne) and the Aspen Music Festival, before earning her bachelor and master of Blue Bird Song (Pima) and Corn-Grinding Song (Lagunas) music degrees in piano performance at Indiana University. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

Olin Levi Warner (1844—1896)

237 East Palace Avenue Santa Fe, NM 87501 800 879-8898 505 989-9888 505 989-9889 Fax [email protected] Paul (Harry Paul) Burlin (American Painter, 1886-1969) Paul Burlin was born in New York in 1886. He received his early education in England before returning to New York at the age of twelve. He worked for a short time as an illustrator under Theodore Dreiser at Delineator magazine, where he was exposed to Progressivist philosophy and politics. He soon grew tired of commercial work and enrolled at the National Academy of Design. There, he received a formal education and refined his technical skills; though he later dropped out to pursue his artistic studies more informally with a group of fellow students. He was also a frequent visitor at Alfred Steiglitz’s ‘291’ gallery. Burlin achieved a great deal of early artistic success. He visited the Southwest for the first time in 1910. Paintings from this visit were received warmly in New York and exhibited in a 1911 exhibition. As a result of his early success, he was the youngest artist (at twenty-six years of age) to participate in the 1913 Armory Show – the revolutionary exhibition of avant-garde European work that can be credited with introducing modern art to the United States and stimulating the development of modernism in America. There, Burlin’s work was exhibited alongside works by such artists as Picasso, Monet, Cézanne, and Duchamp. Later that year, Burlin returned to the Southwest to live. With the images and ideas of the Armory Show still prominent in his mind, Burlin was impressed and moved by what he described as the ‘primeval, erosive, forbidding character of the landscape’. -

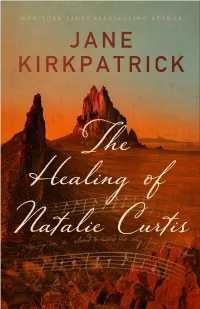

Excerpt 9780800736132.Pdf

“The Healing of Natalie Curtis is Jane Kirkpatrick at her finest, bringing to life a real woman from history, someone who wrestles with issues that are startlingly contemporary, including racism and cultural appropriation. You will find yourself drawn in by the story of Natalie Curtis, an early twentieth- century musical prodigy nearly broken by the rigid conventions of her era, who leaves her loving but somewhat smothering New York family to travel with her brother through the wild expanses of the American Southwest. Curtis finds her health, her voice, and her calling in recording the music of the Southwest’s Native cultures, and de- terminedly fighting for their rights. Fair warning: once you begin this compelling tale, you won’t be able to put it down.” Susan J. Tweit, author of Bless the Birds: Living with Love in a Time of Dying “Natalie Curtis was a force to be reckoned with in the early years of the twentieth century. Her life as a musician, an ethnomusi- cologist, an advocate of social justice for Native Americans, and as a single woman breaking gender and culture barriers to find a life of her own in the American Southwest is a story worth telling and retelling. Kirkpatrick’s novel The Healing of Natalie Curtis is a welcome addition to the body of literature celebrating Curtis’s life.” Lesley Poling- Kempes, author of Ladies of the Canyons: A League of Extraordinary Women and Their Adventures in the American Southwest “‘It’s less time that heals than having a . creative purpose.’ En- capsulating the heart of The Healing of Natalie Curtis, these words landed on my soul with the resonance they must have carried a century ago, when one woman’s quest for physical, emotional, and creative healing led her on a journey that would broaden her vision to see her struggles mirrored in the losses of an Indigenous culture vanishing with alarming brutality— and to Jane Kirkpatrick, The Healing of Natalie Curtis Revell, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2021. -

CHAN 10302 BOOK.Qxd 14/9/06 2:41 Pm Page 2

CHAN 10302 Booklet cover 3/10/05 10:26 AM Page 1 CHAN 10302 CHANDOS Indianische Fantasie Lustspiel-Ouvertüre Gesang vom Reigen der Geister Suite from ‘Die Brautwahl’ Nelson Goerner piano BBC Philharmonic Neeme Järvi CHAN 10302 BOOK.qxd 14/9/06 2:41 pm Page 2 Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924) 1 Lustspiel-Ouvertüre, Op. 38 (1897, revised 1904) 6:28 for Orchestra Allegro molto – Vivacemente – Un poco misuratamente – Tranquillo – Tempo I 2 Indianische Fantasie, Op. 44 (1913–14)* 23:24 for Piano and Orchestra E. Burkard/Lebrecht & Music Arts Library Photo An Miss Natalie Curtis Andante con moto, quasi di marcia – Fantasia. Allegro – Adagio fantastico – Allegretto affettuoso, un poco agitato – Più mosso – Misurato – Cadenza. Fuggitivo, leggiero – Canzone. Un poco meno allegro – Andante quasi lento – Allegro sostenuto – Andantino maestoso – Sostenuto e forte – Cadenza – Lento – Finale. Più vivamente – Deciso – Animato – Allegrissimo 3 Gesang vom Reigen der Geister, Op. 47 (1915) 7:17 Indianisches Tagebuch, Book II (Elegie No. 4) An Charles Martin Loeffler Moderatamente scorrendo – Un poco vivacemente – Ritenendo – A tempo, e tranquillo Ferruccio Busoni 3 CHAN 10302 BOOK.qxd 14/9/06 2:41 pm Page 2 Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924) 1 Lustspiel-Ouvertüre, Op. 38 (1897, revised 1904) 6:28 for Orchestra Allegro molto – Vivacemente – Un poco misuratamente – Tranquillo – Tempo I 2 Indianische Fantasie, Op. 44 (1913–14)* 23:24 for Piano and Orchestra E. Burkard/Lebrecht & Music Arts Library Photo An Miss Natalie Curtis Andante con moto, quasi di marcia – Fantasia. Allegro – Adagio fantastico – Allegretto affettuoso, un poco agitato – Più mosso – Misurato – Cadenza. Fuggitivo, leggiero – Canzone. Un poco meno allegro – Andante quasi lento – Allegro sostenuto – Andantino maestoso – Sostenuto e forte – Cadenza – Lento – Finale. -

Native American Elements in Piano Repertoire by the Indianist And

NATIVE AMERICAN ELEMENTS IN PIANO REPERTOIRE BY THE INDIANIST AND PRESENT-DAY NATIVE AMERICAN COMPOSERS Lisa Cheryl Thomas, B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2010 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Steven Friedson, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Jesse Eschbach, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Thomas, Lisa Cheryl. Native American Elements in Piano Repertoire by the Indianist and Present-Day Native American Composers. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2010, 78 pp., 25 musical examples, 6 illustrations, references, 66 titles. My paper defines and analyzes the use of Native American elements in classical piano repertoire that has been composed based on Native American tribal melodies, rhythms, and motifs. First, a historical background and survey of scholarly transcriptions of many tribal melodies, in chapter 1, explains the interest generated in American indigenous music by music scholars and composers. Chapter 2 defines and illustrates prominent Native American musical elements. Chapter 3 outlines the timing of seven factors that led to the beginning of a truly American concert idiom, music based on its own indigenous folk material. Chapter 4 analyzes examples of Native American inspired piano repertoire by the “Indianist” composers between 1890-1920 and other composers known primarily as “mainstream” composers. Chapter 5 proves that the interest in Native American elements as compositional material did not die out with the end of the “Indianist” movement around 1920, but has enjoyed a new creative activity in the area called “Classical Native” by current day Native American composers. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Since its launch in 1982, the Marco Polo label has for over twenty years sought to draw attention to unexplored repertoire.␣ Its main goals have been to record the best music of unknown composers and the rarely heard works of well-known composers.␣ At the same time it originally aspired, like Marco Polo himself, to bring something of the East to the West and of the West to the East. For many years Marco Polo was the only label dedicated to recording rare repertoire.␣ Most of its releases were world première recordings of works by Romantic, Late Romantic and Early Twentieth Century composers, and of light classical music. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again, particularly those whose careers were affected by political events and composers who refused to follow contemporary fashions.␣ Of particular interest are the operas by Richard Wagner’s son Siegfried, who ran the Bayreuth Festival for so many years, yet wrote music more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck. To Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich, Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan), and Bruder Lustig, which further explores the mysterious medieval world of German legend is now added Der Heidenkönig (The Heathen King).␣ Other German operas included in the catalogue are works by Franz Schreker and Hans Pfitzner. Earlier Romantic opera is represented by Weber’s Peter Schmoll, and by Silvana, the latter notable in that the heroine of the title remains dumb throughout most of the action. -

Famous Composers and Their Music

iiii! J^ / Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/famouscomposerst05thom HAROLD BLEBLffiR^^ PROVO. UTAH DANIEL FRANCOIS ESPRIT AUBER From an engraving by C. Deblois, 7867. 41 .'^4/ rii'iiMia-"- '^'', Itamous COMPOSERS AND THEIR MUSIC EXTRA ILLUSTPATED EDITION o/' 1901 Edited by Theodore Thomas John Knowlej Paine (^ Karl Klauser ^^ n .em^fssfi BOSTON M'^ J B MILLET COMPANY m V'f l'o w i-s -< & Copyright, 1891 — 1894— 1901, By J. B. Millet Company. DANIEL FRANCOIS ESPRIT AUBER LIFE aiore peaceful, happy and making for himself a reputation in the fashionable regular, nay, even monotonous, or world. He was looked upon as an agreeable pianist one more devoid of incident than and a graceful composer, with sparkling and original Auber's, has never fallen to the ideas. He pleased the ladies by his irreproachable lot of any musician. Uniformly gallantry and the sterner sex by his wit and vivacity. harmonious, with but an occasional musical dis- During this early period of his life Auber produced sonance, the symphony of his life led up to its a number of lietier, serenade duets, and pieces of dramatic climax when the dying composer lay sur- drawing-room music, including a trio for the piano, rounded by the turmoil and carnage of the Paris violin and violoncello, which was considered charm- Commune. Such is the picture we draw of the ing by the indulgent and easy-going audience who existence of this French composer, in whose garden heard it. Encouraged by this success, he wrote a of life there grew only roses without thorns ; whose more imp^i/rtant work, a concerto for violins with long and glorious career as a composer ended only orchestra, which was executed by the celebrated with his life ; who felt that he had not lived long Mazas at one of the Conservatoire concerts. -

UNIVERSITY of CINCINNATI August 2005 Stephanie Bruning Doctor Of

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Indian Character Piece for Solo Piano (ca. 1890–1920): A Historical Review of Composers and Their Works D.M.A. Document submitted to the College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance August 2005 by Stephanie Bruning B.M. Drake University, Des Moines, IA, 1999 M.M. College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati, 2001 1844 Foxdale Court Crofton, MD 21114 410-721-0272 [email protected] ABSTRACT The Indianist Movement is a title many music historians use to define the surge of compositions related to or based on the music of Native Americans that took place from around 1890 to 1920. Hundreds of compositions written during this time incorporated various aspects of Indian folklore and music into Western art music. This movement resulted from many factors in our nation’s political and social history as well as a quest for a compositional voice that was uniquely American. At the same time, a wave of ethnologists began researching and studying Native Americans in an effort to document their culture. In music, the character piece was a very successful genre for composers to express themselves. It became a natural genre for composers of the Indianist Movement to explore for portraying musical themes and folklore of Native-American tribes. -

Popular Virtuosity: the Role of the Flute and Flutists in Brazilian Choro

POPULAR VIRTUOSITY: THE ROLE OF THE FLUTE AND FLUTISTS IN BRAZILIAN CHORO By RUTH M. “SUNNI” WITMER A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Ruth M. “Sunni” Witmer 2 Para mis abuelos, Manuel y María Margarita García 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are very few successes in life that are accomplished without the help of others. Whatever their contribution, I would have never achieved what I have without the kind encouragement, collaboration, and true caring from the following individuals. I would first like to thank my thesis committee, Larry N. Crook, Kristen L. Stoner, and Welson A. Tremura, for their years of steadfast support and guidance. I would also like to thank Martha Ellen Davis and Charles Perrone for their additional contributions to my academic development. I also give muitos obrigados to Carlos Malta, one of Brazil’s finest flute players. What I have learned about becoming a musician, a scholar, and friend, I have learned from all of you. I especially want to thank my family – my parents, Mr. Ellsworth E. and Dora M. Witmer, and my sisters Sheryl, Briana, and Brenda– for it was my parent’s vision of a better life for their children that instilled in them the value of education, which they passed down to us. I am also grateful for the love between all of us that kept us close as a family and rewarded us with the happiness of experiencing life’s joys together. -

REGISTER Einheitssachtitel

REGISTER DER EINHEITSSACHTITEL A bassa Porta Paphia Anonym L 7271 A basso porto Spinelli, Niccola (1865 - 1909) L 1 A basso porto Spinelli, Niccola (1865 - 1909) L 2 A basso porto Spinelli, Niccola (1865 - 1909) L 3 A basso porto Spinelli, Niccola (1865 - 1909) L 4 A basso porto Spinelli, Niccola (1865 - 1909) L 5 A Kékszakállú herceg vára Bartók, Béla (1881 - 1945) L 6 A Kékszakállú herceg vára Bartók, Béla (1881 - 1945) L 7 A Kékszakállú herceg vára Bartók, Béla (1881 - 1945) L 8 A Kékszakállú herceg vára Bartók, Béla (1881 - 1945) L 645 A Santa Lucia Tasca, Pierantonio (1864 - 1934) L 9 Abend in Paris, Ein Thiel, Erwin R. ( - ) L 10 Niobe, Nic ( - ) Abenteuer Carl des Zweiten, Ein Vesque von Püttlingen, Johann (1803 - L 14 1883) Abenteuer des Casanova Andreae, Volkmar (1879 - 1962) L 11 Abenteuer einer Neujahrsnacht, Die Heuberger, Richard (1850 - 1914) L 12 Abenteuer einer Neujahrsnacht, Die Heuberger, Richard (1850 - 1914) L 16 Abenteuer einer Neujahrsnacht, Die Mathieu, Max ( - ) L 17 Abenteuer Händels, oder Die Macht des Reinecke, Carl (1824 - 1910) L 13 Liedes, Ein Abenteuer in der Neujahrsnacht, Ein Anonym L 7252 Abenteuer in der polnischen Schenke, Pasticcio L 18 Das Abenteuerin, Die Anonym L 20 Abenteurer, Der Stix, Karl (1873 - 1909) L 19 Aber Otty...! Baderle, Egon ( - ) L 21 Aber Otty...! Baderle, Egon ( - ) L 22 Abreise, Die Albert, Eugen d' (1864 - 1932) L 23 Abreise, Die Albert, Eugen d' (1864 - 1932) L 24 Abreise, Die Albert, Eugen d' (1864 - 1932) L 25 Abreise, Die Albert, Eugen d' (1864 - 1932) L 26 Abreise, Die Albert, Eugen d' (1864 - 1932) L 6066 Abt von St. -

Musical Life in Portland in the Early Twentieth Century

MUSICAL LIFE IN PORTLAND IN THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY: A LOOK INTO THE LIVES OF TWO PORTLAND WOMEN MUSICIANS by MICHELE MAI AICHELE A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2011 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Michele Mai Aichele Title: Musical Life in Portland in the Early Twentieth Century: A Look into the Lives of Two Portland Women Musicians This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Anne Dhu McLucas Chair Lori Kruckenberg Member Loren Kajikawa Member and Richard Linton Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2011 ii © 2011 Michele Mai Aichele iii THESIS ABSTRACT Michele Mai Aichele Master of Arts School of Music and Dance June 2011 Title: Musical Life in Portland in the Early Twentieth Century: A Look into the Lives of Two Portland Women Musicians Approved: _______________________________________________ Dr. Anne Dhu McLucas This study looks at the lives of female musicians who lived and worked in Oregon in the early twentieth century in order to answer questions about what musical opportunities were available to them and what musical life may have been like. In this study I am looking at the lives of the composers, performers, and music teachers, Ethel Edick Burtt (1886-1974) and Mary Evelene Calbreath (1895-1972).