Wise Managment in Business, Politics & Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARENA Annual Report 2019

ARENA Centre for European Studies University of Oslo Annual report 2019 Introduction ARENA Centre for European Studies is an internationally renowned research centre at the University of Oslo. We conduct theoretically oriented and empirically informed basic research on the dynamics of the evolving European political order. This report provides a comprehensive overview of our ongoing projects, publications and events. 2019 marked ARENA’s 25th anniversary and 25 years since the introduction of the EEA Agreement, a period in which ARENA’s research has shaped both the public and scholarly debate in the field of European studies. This was emphasised at the ARENA anniversary conference by Minister of Foreign Affairs Ine Eriksen Søreide, who congratulated ARENA on its long-time contribution, and underlined the continued need to raise awareness and knowledge about European integration for the future. In 2019 ARENA took on, for the fifth time, the coordinator role on an extensive EU project. EU Differentiation, Dominance and Democracy (EU3D) project members from ARENA will work together with academic partners across Europe to provide new insights on the democratic potentials and pitfalls of differentiation in today’s EU. The project’s kick-off conference in Rome brought together more than 50 participants to discuss differentiation in Europe. ARENA’s many other projects ensured an active year for researchers and staff. GLOBUS organised study tours to China and Russia with partners, policy makers and stakeholder to discuss the EU’s role in the world. PLATO held a fourth PhD School on preliminary project findings. ARENA researchers continued to publish research with top tier academic journals and publishers. -

LE19 - a Turning of the Tide? Report of Local Elections in Northern Ireland, 2019

#LE19 - a turning of the tide? Report of local elections in Northern Ireland, 2019 Whitten, L. (2019). #LE19 - a turning of the tide? Report of local elections in Northern Ireland, 2019. Irish Political Studies, 35(1), 61-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2019.1651294 Published in: Irish Political Studies Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2019 Political Studies Association of Ireland.. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:29. Sep. 2021 #LE19 – a turning of the tide? Report of Local Elections in Northern Ireland, 2019 Lisa Claire Whitten1 Queen’s University Belfast Abstract Otherwise routine local elections in Northern Ireland on 2 May 2019 were bestowed unusual significance by exceptional circumstance. -

NEE 2015 2 FINAL.Pdf

ADVERTISEMENT NEW EASTERN EUROPE IS A COLLABORATIVE PROJECT BETWEEN THREE POLISH PARTNERS The City of Gdańsk www.gdansk.pl A city with over a thousand years of history, Gdańsk has been a melting pot of cultures and ethnic groups. The air of tolerance and wealth built on trade has enabled culture, science, and the Arts to flourish in the city for centuries. Today, Gdańsk remains a key meeting place and major tourist attraction in Poland. While the city boasts historic sites of enchanting beauty, it also has a major historic and social importance. In addition to its 1000-year history, the city is the place where the Second World War broke out as well as the birthplace of Solidarność, the Solidarity movement, which led to the fall of Communism in Central and Eastern Europe. The European Solidarity Centre www.ecs.gda.pl The European Solidarity Centre is a multifunctional institution combining scientific, cultural and educational activities with a modern museum and archive, which documents freedom movements in the modern history of Poland and Europe. The Centre was established in Gdańsk on November 8th 2007. Its new building was opened in 2014 on the anniversary of the August Accords signed in Gdańsk between the worker’s union “Solidarność” and communist authorities in 1980. The Centre is meant to be an agora, a space for people and ideas that build and develop a civic society, a meeting place for people who hold the world’s future dear. The mission of the Centre is to commemorate, maintain and popularise the heritage and message of the Solidarity movement and the anti-communist democratic op- position in Poland and throughout the world. -

Unity Amid Division

Renée van Abswoude Unity amid Division Unity amid Division The local impact of and response to the Brexit-influenced looming hard border by ordinary citizens in a border city in Northern Ireland Renée van Abswoude Unity amid Division Credits cover design: Corné van den Boogert Renée van Abswoude Unity amid Division Wageningen University - Social Sciences Unity Amid Division The local impact of and response to the Brexit-influenced looming hard border by ordinary citizens in a border city in Northern Ireland Student Renée van Abswoude Student number 940201004010 E-mail [email protected] Thesis Supervisor Lotje de Vries Email [email protected] Second reader Robert Coates Email [email protected] University Wageningen University and Research Master’s Program International Development Studies Thesis Chair Group (1) Sociology of Development and Change (2) Disaster Studies Date 20 October 2019 3 Renée van Abswoude Unity amid Division “If we keep remembering our past as the implement of how we interrogate our future, things will never change.” - Irish arts officer for the city council, interview 12 April 2019 4 Renée van Abswoude Unity amid Division Abstract A new language of the Troubles in Northern Ireland dominates international media today. This is especially the case in the city of Derry/Londonderry, where media reported on a car bomb on 19 January 2019, its explosion almost killing five passer-by’s. Only three months later, during Easter, the death of young journalist Lyra McKee shocked the world. International media link these stories to one event that has attracted the eyes of the world: Brexit, and the looming hard border between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. -

Debates Posėdžio Stenograma

2014 - 2019 ПЪЛЕН ПРОТОКОЛ НА РАЗИСКВАНИЯТА DEBAŠU STENOGRAMMA ACTA LITERAL DE LOS DEBATES POSĖDŽIO STENOGRAMA DOSLOVNÝ ZÁZNAM ZE ZASEDÁNÍ AZ ÜLÉSEK SZÓ SZERINTI JEGYZŐKÖNYVE FULDSTÆNDIGT FORHANDLINGSREFERAT RAPPORTI VERBATIM TAD-DIBATTITI AUSFÜHRLICHE SITZUNGSBERICHTE VOLLEDIG VERSLAG VAN DE VERGADERINGEN ISTUNGI STENOGRAMM PEŁNE SPRAWOZDANIE Z OBRAD ΠΛΗΡΗ ΠΡΑΚΤΙΚΑ ΤΩΝ ΣΥΖΗΤΗΣΕΩΝ RELATO INTEGRAL DOS DEBATES VERBATIM REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS STENOGRAMA DEZBATERILOR COMPTE RENDU IN EXTENSO DES DÉBATS DOSLOVNÝ ZÁPIS Z ROZPRÁV TUARASCÁIL FOCAL AR FHOCAL NA N-IMEACHTAÍ DOBESEDNI ZAPISI RAZPRAV DOSLOVNO IZVJEŠĆE SANATARKAT ISTUNTOSELOSTUKSET RESOCONTO INTEGRALE DELLE DISCUSSIONI FULLSTÄNDIGT FÖRHANDLINGSREFERAT Сряда - Miércoles - Středa - Onsdag - Mittwoch - Kolmapäev - Τετάρτη - Wednesday Mercredi - Dé Céadaoin - Srijeda - Mercoledì - Trešdiena - Trečiadienis - Szerda L-Erbgħa - Woensdag - Środa - Quarta-feira - Miercuri - Streda - Sreda - Keskiviikko - Onsdag 01.03.2017 Единство в многообразието - Unida en la diversidad - Jednotná v rozmanitosti - Forenet i mangfoldighed - In Vielfalt geeint - Ühinenud mitmekesisuses Eνωμένη στην πολυμορφία - United in diversity - Unie dans la diversité - Aontaithe san éagsúlacht - Ujedinjena u raznolikosti - Unita nella diversità Vienoti daudzveidībā - Susivieniję įvairovėje - Egyesülve a sokféleségben - Magħquda fid-diversità - In verscheidenheid verenigd - Zjednoczona w różnorodności Unida na diversidade - Unită în diversitate - Zjednotení v rozmanitosti - Združena v raznolikosti - Moninaisuudessaan yhtenäinen -

The Welsh Government's Legislative Consent Memorandum On

Welsh Parliament Legislation, Justice and Constitution Committee The Welsh Government’s Legislative Consent Memorandum on the United Kingdom Internal Market Bill November 2020 www.senedd.wales The Welsh Parliament is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people. Commonly known as the Senedd, it makes laws for Wales, agrees Welsh taxes and holds the Welsh Government to account. An electronic copy of this document can be found on the Senedd website: www.senedd.wales/SeneddLJC Copies of this document can also be obtained in accessible formats including Braille, large print, audio or hard copy from: Legislation, Justice and Constitution Committee Welsh Parliament Cardiff Bay CF99 1SN Tel: 0300 200 6565 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @SeneddLJC © Senedd Commission Copyright 2020 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the Senedd Commission and the title of the document specified. Welsh Parliament Legislation, Justice and Constitution Committee The Welsh Government’s Legislative Consent Memorandum on the United Kingdom Internal Market Bill November 2020 www.senedd.wales About the Committee The Committee was established on 15 June 2016. Its remit can be found at: www.senedd.wales/SeneddLJC Committee Chair: Mick Antoniw MS Welsh Labour Current Committee membership: Carwyn Jones MS Dai Lloyd MS Welsh Labour Plaid Cymru David Melding MS Welsh Conservatives The Welsh Government’s Legislative Consent Memorandum on the United Kingdom Internal Market Bill Contents 1. -

Download (3064Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/98850 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications 3 An Integration of Discord: How National Identity Conceptions Activate Resistance to EU Integration in the Popular Press Discourses of Poland, Spain and Great Britain. A thesis submitted to: l'Université Libre de Bruxelles & The University of Warwick (PAIS) For the qualification of: PhD, Politics and International Studies by Andrew Anzur Clement September 2017 4 Abstract The EU has widened and deepened the single market over time according to a transactionalist discourse of common-interests in integration. This rationale holds that as amounts of cross- border movement increase, Member State populations should perceive the single market as beneficial, thus leading to the creation of an affective European identity. Instead, as consequences of integration have become more visible, resistance to the EU has become more pronounced, especially with relation to the Union's right of free movement of persons. This thesis argues that interest-based theories of integration ignore prospects for resilient national identities to influence the accordance of solidarity ties, so as to color interest perceptions within national public spheres. -

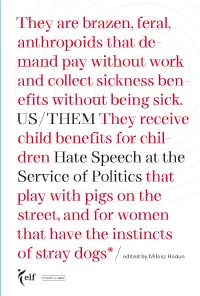

Here: on Hate Speech

They are brazen, feral, anthropoids that de- mand pay without work and collect sickness ben- efits without being sick. US / THEM They receive child benefits for chil- dren Hate Speech at the Service of Politics that play with pigs on the street, and for women that have the instincts of stray dogs * / edited by Miłosz Hodun LGBT migrants Roma Muslims Jews refugees national minorities asylum seekers ethnic minorities foreign workers black communities feminists NGOs women Africans church human rights activists journalists leftists liberals linguistic minorities politicians religious communities Travelers US / THEM European Liberal Forum Projekt: Polska US / THEM Hate Speech at the Service of Politics edited by Miłosz Hodun 132 Travelers 72 Africans migrants asylum seekers religious communities women 176 Muslims migrants 30 Map of foreign workers migrants Jews 162 Hatred refugees frontier workers LGBT 108 refugees pro-refugee activists 96 Jews Muslims migrants 140 Muslims 194 LGBT black communities Roma 238 Muslims Roma LGBT feminists 88 national minorities women 78 Russian speakers migrants 246 liberals migrants 8 Us & Them black communities 148 feminists ethnic Russians 20 Austria ethnic Latvians 30 Belgium LGBT 38 Bulgaria 156 46 Croatia LGBT leftists 54 Cyprus Jews 64 Czech Republic 72 Denmark 186 78 Estonia LGBT 88 Finland Muslims Jews 96 France 64 108 Germany migrants 118 Greece Roma 218 Muslims 126 Hungary 20 Roma 132 Ireland refugees LGBT migrants asylum seekers 126 140 Italy migrants refugees 148 Latvia human rights refugees 156 Lithuania 230 activists ethnic 204 NGOs 162 Luxembourg minorities Roma journalists LGBT 168 Malta Hungarian minority 46 176 The Netherlands Serbs 186 Poland Roma LGBT 194 Portugal 38 204 Romania Roma LGBT 218 Slovakia NGOs 230 Slovenia 238 Spain 118 246 Sweden politicians church LGBT 168 54 migrants Turkish Cypriots LGBT prounification activists Jews asylum seekers Europe Us & Them Miłosz Hodun We are now handing over to you another publication of the Euro- PhD. -

Welsh Labour Manifesto 2021

Moving Wales Forward WELSH LABOUR MANIFESTO 2021 14542_21 Reproduced from electronic media, promoted by Louise Magee, General Secretary, Welsh Labour, on behalf of Welsh Labour, both at 1 Cathedral Road, Cardiff CF11 9HA. Moving Wales Forward CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 WELSH LABOUR’S PLEDGES 5 CHAPTER 1 – HEALTH & WELLBEING 8 CHAPTER 2 – SOCIAL CARE 14 CHAPTER 3 – JOBS & SKILLS 20 CHAPTER 4 – BUILDING A STRONGER, GREENER ECONOMY 26 CHAPTER 5 – A GREENER ENERGY & ENVIRONMENT 32 CHAPTER 6 – SCHOOLING, LEARNING & EDUCATION FOR ALL 38 CHAPTER 7 – LEADING ON EQUALITIES 44 CHAPTER 8 – WELSH LANGUAGE, CULTURE, SPORT & TOURISM 50 CHAPTER 9 – OUR HOMES, COMMUNITIES & COUNCILS 56 CHAPTER 10 – OUR NATION 62 CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION This pandemic has tested all of us. Many of Social solidarity is at the heart of the Labour us have lost family members, friends, and movement. Never have we seen that more widely neighbours to Covid-19, and we know that displayed than in Wales during these awful times. there are others still struggling with the lasting We have stood together, shoulder to shoulder, impact of the disease upon their health and working, whenever we could, with the other wellbeing. devolved nations and the UK Government. We have, all of us, battled against the pandemic. Here are some of the specific actions that we have We owe a big debt of gratitude to those heroes in taken to combat the pandemic. health, care services, the police, education, other key workers and to countless volunteers. We have The credit for every single one of them lies relied on them all to help us through the crisis. -

Einsel Thesis 2012.Pdf

United by Guilt: The Influence of Guilt on Dimensions of Support Regarding European Union Integration A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at George Mason University, and the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Malta by Anthony Owet Einsel Bachelor of Arts Creighton University, 2008 Director: Derek Lutterbeck, Deputy Director; Holder of the Swiss Chair & Lecturer in International History Mediterranean Academy of Diplomatic Studies Fall Semester 2012 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia University of Malta Valletta, Malta Copyright 2012 Anthony O. Einsel All Rights Reserved ii Dedication For Europe iii Acknowledgments This is special thanks for everybody who believed in the project and supported me all the way through. I thank Dr. Derek Lutterbeck for the recommendation to visit Brussels and interview MEPs, as well as any and all input for my work. I would also like to thank the professors at both MEDAC and S‐CAR for the very knowledgeable and insightful views toward Conflict Resolution and Mediterranean Security. This is also extended to the other 21 students of the joint programme, who made the nine months of study and dissertation exercise… a bit more tolerable. I would also like to thank Professor Edward Scicluna, Messrs Roger Helmer, Morten Messerschmidt, Sampo Terho, and Peter Simon for their time and answers to my interview questions. Special thanks go to Mr. Andrew Reed, who spoke on behalf of Mr. Nigel Farage, and has been very gracious to field any and all questions which were sent his way. Special Thanks goes out to Mr. -

Samuel A. T. Johnston

APPENDICES Samuel A. T. Johnston © The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature 341 Switzerland AG 2021 M. Gallagher et al. (eds.), How Ireland Voted 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66405-3 342 APPENDIX A: RESULTS OF THE GENEraL ELECTION, 8 FEBrUarY 2020 Table A1.1 Electorate, valid votes and votes for each party APPENDICES Constituency Electorate Valid votes Sinn Féin Fianna Fine Gael Green Labour SocDems S–PBP Aontú Others Fáil Carlow–Kilkenny 114,343 73,643 17,493 27,459 15,999 4942 2208 0 1558 0 3984 Cavan–Monaghan 110,190 72,183 26,476 18,161 19,233 2501 983 0 830 3840 159 Clare 91,120 59,495 8987 20,254 13,375 5624 0 0 1196 0 10,059 Cork East 89,998 54,544 12,587 14,440 10,697 3749 6610 0 0 1337 5124 Cork North-Central 87,473 51,778 13,811 12,714 7802 3205 2561 1121 3703 1325 5536 Cork North-West 71,685 46,370 0 18,279 15,403 3495 0 3845 0 3877 1471 Cork South-Central 90,916 57,140 14,057 20,259 12,155 5379 1263 1077 764 1350 836 Cork South-West 69,127 44,338 4777 10,339 8391 1647 0 4696 427 515 13,546 Donegal 125,911 77,452 34,935 15,816 10,677 1656 0 0 0 2382 11,986 Dublin Bay North 112,047 71,606 21,344 10,294 13,435 5042 8127 6229 2131 973 4031 Dublin Bay South 80,764 39,591 6361 5474 10,970 8888 3121 1801 1002 0 1974 Dublin Central 61,998 31,435 11,223 3228 4751 3851 1702 2912 977 583 2208 Dublin Fingal 101,045 63,440 15,792 13,634 9493 8400 4513 2206 1161 0 8241 Dublin Mid-West 74,506 45,452 19,463 5598 7988 2785 1541 0 3572 0 4505 Dublin North-West 54,885 32,386 14,375 3902 3579 1548 848 6124 1215 0 795 -

Download (PDF)

Editor in Chief Editorial Board Agata Górny Zuzanna Brunarska Kathy Burrell Piotr Koryś Associate Editor in Chief Yana Leontiyeva Magdalena Lesińska Aleksandra Grzymała-Kazłowska Stefan Markowski Justyna Nakonieczna-Bartosiewicz Aneta Piekut Managing Editor Paolo Ruspini Renata Stefańska Brygida Solga Paweł Strzelecki Anne White Advisory Editorial Board Marek Okólski, Chairman Solange Maslowski SWPS, UW, Warsaw ChU, Prague Olga Chudinovskikh Ewa Morawska MSU, HSE, Moscow UE, Essex Barbara Dietz Mirjana Morokvasic IOS, Regensburg CNRS, Paris Boris Divinský Jan Pakulski Bratislava UTAS, Hobart Dušan Drbohlav Dorota Praszałowicz ChU, Prague JU, Cracow Elżbieta Goździak Krystyna Romaniszyn GU, Washington, CeBaM, Poznan JU, Cracow Agnes Hars John Salt Kopint-Tárki, Budapest UCL, London Romuald Jończy Dumitru Sandu WUE, Wroclaw UB, Bucharest Paweł Kaczmarczyk Krystyna Slany UW, Warsaw JU, Cracow Olga Kupets Dariusz Stola NaUKMA, Kyiv PAS, CC, Warsaw Cezary Żołędowski UW,Warsaw Adaptation of the CEEMR website – modernisation and update of the content – for application for indexation in international publications databases, in particular Scopus and DOAJ, as well as proofreading of articles in English are financed from the funds of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education allocated for the dissemination of science under the agreement 765/P-DUN/2016. ISSN 2300–1682 Editorial office: Centre of Migration Research, University of Warsaw, Banacha 2b, 02–097 Warsaw, e-mail: [email protected] © Copyright by Centre of Migration Research, Polish Academy