Some Conditions of Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Four Freedoms

ACTIVITY 1.9 WWhathat IIss FFreedom?reedom? ACTIVITY 1.9 PLAN Suggested Pacing: 2 50-minute Learning Targets class periods • Analyze the use of rhetorical features in an argumentative text. LEARNING STRATEGIES: SOAPSTone, Socratic • Compare how a common theme is expressed in different texts. Seminar TEACH • Present, clarify, and challenge ideas in order to propel conversations. 1 Read the Preview and the Setting Preview a Purpose for Reading sections with In this activity, you will read a speech delivered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt My Notes your students. Help them understand and two parts of the Constitution of the United States to root your thinking in the that they will be reading seminal foundational documents of the nation. texts of the United States to compare Setting a Purpose for Reading definitions offreedom . These texts are primary sources. Remind • Underline words and phrases that define freedom. students that primary sources are • Highlight words and phrases that describe the concepts of America and American. valuable, and context is important in • Put a star next to particularly moving rhetoric. understanding them. • Circle unknown words and phrases. Try to determine the meaning of the words 2 FIRST READ: Based on the by using context clues, word parts, or a dictionary. complexity of the passage and your knowledge of your students, you ABOUT THE AUTHOR may choose to conduct the first President Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivered this State of the Union speech reading in a variety of ways: on January 6, 1941. The speech outlines four key human rights. It acted as a reminder to the nation of the reasons for supporting Great Britain in its fight • independent reading against Germany. -

“American Chronicles: the Art of Norman Rockwell at TAM” Published in Artdish, March 2011 2011 Jane Richlovsky

“American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell at TAM” published in Artdish, March 2011 2011 Jane Richlovsky Norman Rockwell's painting "Discovery", currently on display at the Tacoma Art Museum, depicts a pajama-clad young boy finding a Santa Claus suit and false beard in Dad's bureau drawer, incriminating evidence of the old man's fakery. The picture appeared on the cover of the December 29, 1956 Saturday Evening Post. It's hard at first to get past the boy's facial expression. His eyes are popping out of his head, in a way that irritatingly foreshadows the ubiquitous Macauley Caulkin "Home Alone" publicity shot. However unfortunate this association, the expression is so utterly unconvincing as a portrayal of having one's cherished mythology punctured, that one can't help but think the kid never believed in Santa in the first place. Considering that this is one of many Rockwell paintings that repeatedly revisit the Santa-unmasking narrative over decades, you have to wonder: Is the guy responsible for our vision of the American Myth perhaps telling us we shouldn't be so surprised or upset that it's all made up? I've always found sunny, idealized, 1950's-style Leave-it-to-Beaver archetypal America intriguing, compelling, and horrifying. I'm far from alone in this, but I have spent more time than most people immersed in its ephemera, interrogating, digesting, cutting up, reconfiguring, and spitting back out endless images from midcentury domestic magazines. Imagine my shock when, after all that, putting together a show of the resulting paintings, I encounter a dealer's misbegotten press release, or an enthusiastic patron, praising what I thought was my scathing critique as a fond, nostalgic look back at a "simpler time". -

F. D. Roosevelt, Norman Rockwell & the Four Freedoms (1943)

F. D. Roosevelt, Norman Rockwell & the Four Freedoms (1943) Excerpt from Roosevelt’s January 16, 1941 speech before the U.S. Congress: “In the future days which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms. The first is freedom of speech and expression -- everywhere in the world. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way -- everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want -- which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants -- everywhere in the world. The fourth is freedom from fear -- which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor-- anywhere in the world. That is no vision of a distant millennium. It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation. That kind of world is the very antithesis of the so-called new order of tyranny which the dictators seek to create with the crash of a bomb. To that new order we oppose the greater conception -- the moral order. A good society is able to face schemes of world domination and foreign revolutions alike without fear. Since the beginning of our American history, we have been engaged in change -- in a perpetual peaceful revolution -- a revolution which goes on steadily, quietly adjusting itself to changing conditions -- without the concentration camp or the quick-lime in the ditch. -

Keane, for Allowing Us to Come and Visit with You Today

BIL KEANE June 28, 1999 Joan Horne and myself, Ann Townsend, interviewers for the Town of Paradise Valley Historical Committee are privileged to interview Bil Keane. Mr. Keane has been a long time resident of the Town of Paradise Valley, but is best known and loved for his cartoon, The Family Circus. Thank you, Mr. Keane, for allowing us to come and visit with you today. May we have your permission to quote you in part or all of our conversation today? Bil Keane: Absolutely, anything you want to quote from it, if it's worthwhile quoting of course, I'm happy to do it. Ann Townsend: Thank you very much. Tell us a little bit about yourself and what brought you to hot Arizona? Bil Keane: Well, it was a TWA plane. I worked on the Philadelphia Bulletin for 15 years after I got out of the army in 1945. It was just before then end of 1958 that I had been bothered each year with allergies. I would sneeze in the summertime and mainly in the spring. Then it got in to be in the fall, then spring, summer and fall. The doctor would always prescribe at that time something that would alleviate it. At the Bulletin I was doing a regular comic and I was editor of their Fun Book. I had a nine to five job there and we lived in Roslyn which was outside Philadelphia and it was one hour and a half commute on the train and subway. I was selling a feature to the newspapers called Channel Chuckles, which was the little cartoon about television which I enjoyed doing. -

Margaret C. Rung Professor of History Director, History Program and Center for New Deal Studies Roosevelt University

Margaret C. Rung Professor of History Director, History Program and Center for New Deal Studies Roosevelt University 430 S. Michigan Ave., Chicago, Illinois 60605 (w) 312-341-3724, Rm 834 e-mail: [email protected] Education: Ph.D., The Johns Hopkins University (History) M.A., The Johns Hopkins University (History) B.A., Oberlin College (Phi Beta Kappa) Professional Positions: Professor of History, Roosevelt University Chair, Department of History and Philosophy, 2013-2017 Director of the Center for New Deal Studies, Roosevelt University 2002- Associate Dean, College of Arts & Sciences, Roosevelt University, 2001-2005 Program Coordinator, History, 1999-2000, 2001-2005 Visiting Fulbright Lecturer, University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia, 2000-2001 Assistant Professor of History, Mount Allison University, 1993-1994 Research/Professional Experience: Research & Editorial Assistant, The Dwight David Eisenhower Papers Project, Baltimore, Maryland, 1987-1993 Research Historian, History Associates, Inc., Rockville, Maryland, 1985-1990 *Significant projects: Rung, "Celebrating One Hundred Years: A History of Florida National Bank." Recipient of Golden Image Award, Florida Public Relations Association, April 1988. *Research assistance on: Richard G. Hewlett, Jessie Ball DuPont. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1992; Rodney P. Carlisle, Where the Fleet Begins: A History of the David Taylor Naval Research Center, 1898-1998. Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center, 1998; Dian O.Belanger, Managing American Wildlife: A History of the International Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1988. Archival Assistant, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C., 1985 Publications: With Erik Gellman, “The Great Depression” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of American History, ed. Jon Butler. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. -

Freedom from Fear? the Oxford American

Staddon, J. (1996) Freedom from fear? The Oxford American. Spring, pp. 103-106. Freedom from Fear? How belief in a pain-free utopia has discredited punishment and de-civilized society. by John Staddon Successful political slogans are usually phony. They succeed because they promise gain without pain, the reconcil- ing of the irreconcilable and win-win in a zero-sum world. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “four freedoms” are still remembered after two generations. Freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear all sound very fine, but this slogan bears scrutiny no better than others. Freedom of speech and religion are reasonable enough, perhaps. But freedom from want is problematic: Who shall define ‘want’? When does ‘want’ or ‘need’ turn into ‘wish’ and ‘desire’? And whose freedom to spend his own money shall be abridged to satisfy the presumed needs of others? But most pernicious of all is “freedom from fear,” because it seems self-evident. Punishment and the Creed of Mental Health Yet the idea that mankind could ever be free of fear is as odd as it is recent. The ancients knew the world as full of evil spirits. Sin and retribution are at the root of Judaeo-Christianity. Modern biology sees evolution as fre- quently, if not invariably, “red in tooth and claw.” But ever since Freud, a new creed, the creed of psychotherapy, has offered the prospect of mental perfection, of life not just free of evil but innocent even of the concept. The vari- eties of professional psychology and psychiatry from psychoanalysis to behaviorism, while they have argued about everything else, agree that fear can and should be banished. -

Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg

Smithsonian American Art Museum TEACHER’S GUIDE from the collections of GEORGE LUCAS and STEVEN SPIELBERG 1 ABOUT THIS RESOURCE PLANNING YOUR TRIP TO THE MUSEUM This teacher’s guide was developed to accompany the exhibition Telling The Smithsonian American Art Museum is located at 8th and G Streets, NW, Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and above the Gallery Place Metro stop and near the Verizon Center. The museum Steven Spielberg, on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in is open from 11:30 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. Admission is free. Washington, D.C., from July 2, 2010 through January 2, 2011. The show Visit the exhibition online at http://AmericanArt.si.edu/rockwell explores the connections between Norman Rockwell’s iconic images of American life and the movies. Two of America’s best-known modern GUIDED SCHOOL TOURS filmmakers—George Lucas and Steven Spielberg—recognized a kindred Tours of the exhibition with American Art Museum docents are available spirit in Rockwell and formed in-depth collections of his work. Tuesday through Friday from 10:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m., September through Rockwell was a masterful storyteller who could distill a narrative into December. To schedule a tour contact the tour scheduler at (202) 633-8550 a single moment. His images contain characters, settings, and situations that or [email protected]. viewers recognize immediately. However, he devised his compositional The docent will contact you in advance of your visit. Please let the details in a painstaking process. Rockwell selected locations, lit sets, chose docent know if you would like to use materials from this guide or any you props and costumes, and directed his models in much the same way that design yourself during the visit. -

Curtis Publishing Company Records

** Preliminary inventory ** Collection 3115 Curtis Publishing Company Records ca. 1891-1968 16 boxes, 4 volumes, 14.4 lin. feet Contact: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107 Phone: (215) 732-6200 FAX: (215) 732-2680 http://www.hsp.org Processed by: Titus T. Moolathara Processing Completed: May 2009 Restrictions: None © 2009 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. Curtis Publishing Company Collection 3115 ** Preliminary inventory ** Curtis Publishing Company Records, ca. 1891- 1968 16 boxes, 4 volumes, 14.4 lin. feet Collection 3115 Abstract Cyrus H. Curtis, a pioneer of modern magazine publishing in the United States, established the Curtis Publishing Company in 1891 in Philadelphia. Prior to this, Cyrus Curtis started his career by publishing a local weekly in Portland, Oregon, until a fire destroyed the plant. He later moved to Boston, Massachusetts, where he started to publish The People’s Ledger magazine. He continued to publish the magazine after he moved to Philadelphia in 1876. The Curtis Publishing Company became one of the most influential publishing companies in the United States during the early 20th century, having published Ladies Home Journal, The Saturday Evening Post, Holiday, The American Home, Jack & Jill, and Country Gentleman . The collection contains financial documents that include annual reports, reports to the Board of Directors, information on annual meetings, ledgers, bills, deeds, contracts, Old Age and Social Security Records, payroll accounts, etc. In Boxes 3 to 6 there is information on standards for advertisements, writing and advertising case histories; miscellaneous publications on business advertising; and some materials on history of the business press. -

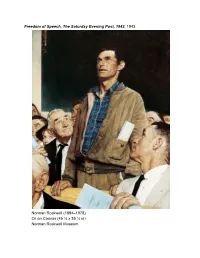

2-A Rockwell Freedom of Speech

Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943, 1943 Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) Oil on Canvas (45 ¾ x 35 ½ in) Norman Rockwell Museum NORMAN ROCKWELL [1894–1978] 19 a Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943 After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, What is uncontested is that his renditions were not only vital to America was soon bustling to marshal its forces on the home the war effort, but have become enshrined in American culture. front as well as abroad. Norman Rockwell, already well known Painting the Four Freedoms was important to Rockwell for as an illustrator for one of the country’s most popular maga- more than patriotic reasons. He hoped one of them would zines, The Saturday Evening Post, had created the affable, gangly become his statement as an artist. Rockwell had been born into character of Willie Gillis for the magazine’s cover, and Post read- a world in which painters crossed easily from the commercial ers eagerly followed Willie as he developed from boy to man world to that of the gallery, as Winslow Homer had done during the tenure of his imaginary military service. Rockwell (see 9-A). By the 1940s, however, a division had emerged considered himself the heir of the great illustrators who left their between the fine arts and the work for hire that Rockwell pro- mark during World War I, and, like them, he wanted to con- duced. The detailed, homespun images he employed to reach tribute something substantial to his country. a mass audience were not appealing to an art community that A critical component of the World War II war effort was the now lionized intellectual and abstract works. -

BAM 50 State Initiative Art Project—A Partnership with for Freedoms—Activates Civic Engagement Through Art Work Creation, Saturday, Oct 20

BAM 50 State Initiative Art Project—a partnership with For Freedoms—activates civic engagement through art work creation, Saturday, Oct 20 Free public event will be led by Brooklyn visual artist Katherine Toukhy Oct 5, 2018/Brooklyn, NY—The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) has partnered with For Freedoms in an afternoon of civic engagement on Saturday, Oct 20 from 1–3pm at the South Site Plaza (Lafayette Ave, corner of Flatbush Ave). Attendees will participate in an art-making project, led by Brooklyn visual artist Katherine Toukhy, to create and share social and political statements with the community. Images of finished artworks will be photographed and displayed on BAM’s outdoor digital signpost on the corner of Flatbush Ave and Lafayette Ave—running on a loop until the mid-term elections in November. BAM’s VP of Education and Community Engagement Coco Killingsworth said, “We’re excited to join with For Freedoms and Katherine Toukhy in gathering community members for this creative civic activation. We hope this event inspires all of us to use our voices to engage in the democratic process.” For Freedoms started in 2016 as a platform for civic engagement, discourse, and direct action for artists in the United States. Inspired by Norman Rockwell’s 1943 painting of the four universal freedoms articulated by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1941—freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear—For Freedoms seeks to use art to deepen public discussions of civic issues and core values, and to clarify that citizenship in American society is deepened by participation, not by ideology. -

REVISITING the FOUR FREEDOMS by Donald M

EXCLUSIVE MCUF FEATURE REVISITING THE FOUR FREEDOMS By Donald M. Bishop PHOTO: The Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, located on an island in New York's East River, opened in 2012 3 • MARINE CORPS UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION • SUMMER 2019 EXCLUSIVE MCUF FEATURE Modern political warfare now includes both cyber and information operations. At MCU, Bren Chair of Strategic Communications Donald Bishop focuses his teaching and presentations on the “information” or “influence” dimension of conflict – disinformation, propaganda, persuasion, hybrid warfare – now enabled by the internet and social media. And he emphasizes that Americans, as they confront violent extremism and other threats, must know and be confident of the American values they defend. "Thanks, Grandpa, for coming to my game." Why look back at The Four Freedoms? First, in my classes at Marine Corps University, I’ve discovered that the current "I enjoyed it too, Jack. We men in our eighties don't get generation of Marines have never heard of them. Of Norman out as often as we wish. Seeing you score a run was Rockwell’s four famous paintings, they have seen only one – something. But you know, I noticed something else today. the family at Thanksgiving – and they don’t know they were "When you were at the plate, it carried me back to part of a series. Second – when Americans must articulate watching my older brother in the batter's box. You held the “what we’re for” (rather than “what we’re against”) – whether bat like he did. You have the same stance and the same in the war on terrorism or in a future of great power competi- swing. -

Denver Art Museum to Present the Power of Art in Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom Traveling Exhibition Features Depictions of Franklin D

Images available upon request. Denver Art Museum to Present the Power of Art in Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom Traveling exhibition features depictions of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms alongside contemporary selections by artists responding to these freedoms today DENVER—June 19, 2020—The Denver Art Museum (DAM) will soon open Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom, an exhibition focused on the artist’s 1940s depictions of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms and a contemporary response to these freedoms. Popularized by Rockwell’s interpretation following President Roosevelt’s 1941 speech, the freedoms include the Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear. Organized and curated by the Norman Rockwell Museum and curated locally by Timothy J. Standring, Gates Family Foundation Curator at the Denver Art Museum, with contemporary works from the museum’s own collections curated by Becky Hart, Vicki and Kent Logan Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, the exhibition will be on view from June 26, 2020 to Sept. 7, 2020, in the Anschutz and Martin & McCormick special exhibition galleries. “The presentation of Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom is the most comprehensive traveling exhibition to date of creative interpretations of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms,” said Christoph Heinrich, Frederick and Jan Mayer Director of the DAM. “We look In the 1940s, Roosevelt’s administration turned to the forward to presenting works that will challenge our visitors arts to help Americans understand the necessity of to consider the concepts of the common good, civic defending and protecting the Four Freedoms, which were engagement and civil discourse through artworks of the not immediately embraced, but later came to be known past and present.” as enduring ideals.