Psalms 73–150

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Crisis in Faith: an Exegesis of Psalm 73

Restoration Quarterly 17.3 (1974) 162-184. Copyright © 1974 by Restoration Quarterly, cited with permission. A Crisis in Faith: An Exegesis of Psalm 73 TERRY L. SMITH Starkville, Mississippi Introduction Psalm 73 is a striking witness to the vitality of the individual life of faith in Israel. It represents the struggles through which the Old Testament faith had to pass. The psalm, a powerful testimony to a battle that is fought within one's soul, reminds one of the book of Job.1 Experiencing serious threat to his assurance of God in a desperate struggle with the Jewish doctrine of retribution, the poet of Psalm 73 raised the question, "How is Yahweh's help to and blessing of those who are loyal to him realized in face of the prosperity of the godless?"2 His consolation is the fact that God holds fast to the righteous one and "remains his God in every situation in life," and even death cannot remove the communion between them.3 He finds a "solution" not in a new or revised interpretation of the old retribution doctrine, but in a "more profound vision of that in which human life is truly grounded, and from which it derives its value."4 But Weiser argues, and rightly so, that what is at stake here is more than a mere theological or intellectual problem; it is a matter of life or death—the question of the survival of faith generally.5 The poem represents an 1. A. Weiser, The Psalms, Old Testament Library (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1962), p. -

Psalms 73-89 the Psalms: Jesus’ Prayer Book

Book III - Psalms 73-89 The Psalms: Jesus’ Prayer Book My father valued his tools. Back in his day he was a slide-rule totting mathematician by vocation and a hammer-swinging carpenter by avocation. He loved his tools. He kept track of them, used them for their specific function, and returned them to their designated place. Nothing made a job go better than having the right tool. My dad took special pride in his wood turning lathe. A lathe is to a furniture-maker what a potter’s wheel is to the potter. With practice my father became skilled in turning out matching table legs. Of all his tools this is the one that reminds me most of the Psalms. A block of wood, locked in place, rotating at variable speeds, powered by an electric motor. The craftsman’s blade carving the wood into the desired shape. The Psalms are the right tool for shaping our spirituality and giving substance to our communion with God. They are soul- carving tools, to use Gregory of Nyssa’s metaphor. Each psalm is its own unique instrument, “and these instruments are not alike in shape,” but all share the common purpose of “carving our souls to the divine likeness.”1 We have plenty of tools for doing and getting, but as Eugene Peterson insists, we need “the primary technology of the Psalms, essential tools for being and becoming human.”2 The Psalms are instrumental in the care of souls. John Calvin entitled the Psalms, “An Anatomy of all the Parts of the Soul,” because there is not an emotion of which any one can be conscious of that is not represented in the Psalms.3 Like an MRI, the Psalms are diagnostic. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

Exegesis of the Psalms “Selah”

Notes ! 147 BIBLE STUDY METHODS: PSALMS The Psalms are emotional. At times, God speaks too, but most of what we read are man’s words directed toward heaven. All these words are completely inspired by God. Our issue is to determine how they function as God’s Word for us. The Psalms are not: • doctrinal teaching - No! • biblical commands on our behavior - No! • illustrations of biblical principles - No! They provide examples of how people expressed themselves to God (rightly or wrongly). They give us pause to think about (1) God, and (2) our relationships to God. They ask us to consider the “ways of God.” Exegesis of the Psalms Separate them by types. Understand their different forms and their different functions. The New Testament contains 287 Old Testament quotes. 116 are from Psalms. The 150 Psalms were written over a period of about 1000 years. Moses wrote Psalm 90 in 1400B.C. Ezra wrote Psalm 1 and Psalm 119 about 444 B.C. Our task is to view the Psalms through the lens of Salvation History. “Selah” The Psalms are poetry and songs. The music is lost to us. “Selah” was intended to signal a musical pause. It’s not necessary to read it out loud. It’s a signal to pause and meditate. Though the Psalms are different from each other, they all emphasize the spirit of the Law, not the letter. Do not use them to form doctrines, independent of New Testament writings. The Psalms are emotional poetry. They often exaggerate through the emotions of their writers. The language is picturesque. -

HOPE in the WORD Is a Plan for You to Connect with God by Being in YOUR Bible for 90 Days

HOPE IN THE WORD is a plan for you to connect with God by being in YOUR bible for 90 days. The format will be Facebook Live from Monday to Thursday @ 10am and will allow you the flexibility to listen in/read at your own pace. In this custom plan, we will read ~ 33% of the Bible, from Old Testament accounts to all the Psalms, Proverbs, the gospel of Mark, and several of the New Testament epistles including Romans, Philippians, and others. Join us for 90 days of being fed with the Word of God! DAY DATE READING DONE 1 Jan 4, 2021 Mark 1-3; Proverbs 1 2 Jan 5, 2021 Mark 4-5; Psalm 1-2 3 Jan 6, 2021 Mark 6-7; Psalm 3-4; Romans 1 4 Jan 7, 2021 Mark 8-9; Psalm 4-5 5 Jan 11, 2021 Mark 10-12; Romans 2 6 Jan 12, 2021 Mark 13-14; Proverbs 2 7 Jan 13, 2021 Mark 15-16; Psalm 6-7; Romans 3 8 Jan 14, 2021 Genesis 1-2; Psalm 8-9 9 Jan 18, 2021 Genesis 3-4; Romans 4 10 Jan 19, 2021 Genesis 6-8; Psalm 10-11 11 Jan 20, 2021 Genesis 7-9; Psalm 12 12 Jan 21, 2021 Genesis 11-12; Romans 5 13 Jan 25, 2021 Genesis 13-14; Psalm 13-15 14 Jan 26, 2021 Genesis 15-17; Romans 6 15 Jan 27, 2021 Genesis 18-19; Psalm 16-17 16 Jan 28, 2021 Genesis 20-21; Romans 7 17 Feb 1, 2021 Genesis 22; Psalm 18-19; Proverbs 3-4 18 Feb 2, 2021 Genesis 23-24; Psalm 20 19 Feb 3, 2021 Genesis 25-26; Proverbs 5; Romans 8 20 Feb 4, 2021 Genesis 27-28; Psalm 21-22 21 Feb 8, 2021 Genesis 29-30; Psalm 23-25 22 Feb 9 2021 Genesis 31-32; Proverbs 6 23 Feb 10, 2021 Genesis 33-34; Romans 9-10 24 Feb 11, 2021 Genesis 35,37; Romans 11 25 Feb 15, 2021 Genesis 38-39; Psalm 26-28 26 Feb 16, 2021 Genesis -

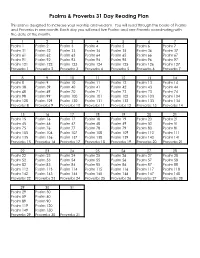

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

Week 95. Psalms

Psalms Part 8 Syllabus Featured Week Psalm Type of Psalm Teacher 1 137 Imprecatory Psalms General Introduction 2 1 Introduction to Psalms Mike Mazzalongo 3 15 Wisdom Psalms Mike Mazzalongo 4 19 Nature Psalms Mike Mazzalongo 5 146 Praise Psalms Christopher Ash 6 74 Psalms of Lament Christopher Ash 7 130 Songs of Ascent Alistair Begg Part 1 Psalm 137 “In Psalms, it talks about God basically celebrating taking babies and smashing their heads against the rocks.” Bob Seidensticker, 2007 Psalm 137 1 By the rivers of Babylon we sit down and weep when we remember Zion. 2 On the poplars in her midst we hang our harps, 3 for there our captors ask us to compose songs; those who mock us demand that we be happy, saying: “Sing for us a song about Zion!” 4 How can we sing a song to the Lord in a foreign land? 5 If I forget you, O Jerusalem, may my right hand be crippled! 6 May my tongue stick to the roof of my mouth, if I do not remember you, and do not give Jerusalem priority over whatever gives me the most joy. 7 Remember, O Lord, what the Edomites did on the day Jerusalem fell. They said, “Tear it down, tear it down, right to its very foundation!” 8 O daughter Babylon, soon to be devastated! How blessed will be the one who repays you for what you dished out to us! 9 How blessed will be the one who grabs your babies and smashes them on a rock! In light of the recent execution of 21 Christians and capture of hundreds more in Syria, perhaps it’s time to ask, “Should we be praying the imprecatory psalms against ISIS?” Written in the theocratic context of Israel, when God himself had a throne on earth, these psalms (e.g., Ps. -

Commentary on Psalms - Volume 3

Commentary on Psalms - Volume 3 Author(s): Calvin, John (1509-1564) Calvin, Jean (1509-1564) (Alternative) (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Calvin found Psalms to be one of the richest books in the Bible. As he writes in the introduction, "there is no other book in which we are more perfectly taught the right manner of praising God, or in which we are more powerfully stirred up to the performance of this religious exercise." This comment- ary--the last Calvin wrote--clearly expressed Calvin©s deep love for this book. Calvin©s Commentary on Psalms is thus one of his best commentaries, and one can greatly profit from reading even a portion of it. Tim Perrine CCEL Staff Writer This volume contains Calvin©s commentary on chapters 67 through 92. Subjects: The Bible Works about the Bible i Contents Commentary on Psalms 67-92 1 Psalm 67 2 Psalm 67:1-7 3 Psalm 68 5 Psalm 68:1-6 6 Psalm 68:7-10 11 Psalm 68:11-14 14 Psalm 68:15-17 19 Psalm 68:18-24 23 Psalm 68:25-27 29 Psalm 68:28-30 33 Psalm 68:31-35 37 Psalm 69 40 Psalm 69:1-5 41 Psalm 69:6-9 46 Psalm 69:10-13 50 Psalm 69:14-18 54 Psalm 69:19-21 56 Psalm 69:22-29 59 Psalm 69:30-33 66 Psalm 69:34-36 68 Psalm 70 70 Psalm 70:1-5 71 Psalm 71 72 Psalm 71:1-4 73 Psalm 71:5-8 75 ii Psalm 71:9-13 78 Psalm 71:14-16 80 Psalm 71:17-19 84 Psalm 71:20-24 86 Psalm 72 88 Psalm 72:1-6 90 Psalm 72:7-11 96 Psalm 72:12-15 99 Psalm 72:16-20 101 Psalm 73 105 Psalm 73:1-3 106 Psalm 73:4-9 111 Psalm 73:10-14 117 Psalm 73:15-17 122 Psalm 73:18-20 126 Psalm 73:21-24 -

1 Pastor Marc Wilson for Disorienting Times May 2020 a PLEA FOR

Pastor Marc Wilson For Disorienting Times May 2020 A PLEA FOR GOD’S REMEMBRANCE—AS THE PEOPLE REMEMBER—SO, YAHWEH WILL RISE UP An Exegesis of Psalm 74 (NIV) A maskil of Asaph. A Plea for God’s Remembrance (1–3) An Address and Complaint to God Regarding Indefinite Rejection (1) 1 O God, why have you rejected us forever? Why does your anger smolder against the sheep of your pasture? A Petition for God to Remember the Redeemed (2) 2 Remember the nation you purchased long ago, the people of your inheritance, whom you redeemed— Mount Zion, where you dwelt. A Petition for God to Return to the Ruins (3) 3 Turn your steps toward these everlasting ruins, all this destruction the enemy has brought on the sanctuary. Remembering the Roaring of Foes Who Brought Ruin (4–8) 4 Your foes roared in the place where you met with us; they set up their standards as signs. 5 They behaved like men wielding axes to cut through a thicket of trees. 6 They smashed all the carved paneling with their axes and hatchets. 7 They burned your sanctuary to the ground; they defiled the dwelling place of your Name. 8 They said in their hearts, “We will crush them completely!” They burned every place where God was worshiped in the land. Restating the Complaint to God Regarding Indefinite Rejection while Exiled (9–11) Amid the Absence of Signs (9) 9 We are given no signs from God; no prophets are left, and none of us knows how long this will be. -

Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures Steven Dunn Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures Steven Dunn Marquette University Recommended Citation Dunn, Steven, "Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures" (2009). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 13. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/13 Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures By Steven Dunn, B.A., M.Div. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin December 2009 ABSTRACT Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures Steven Dunn, B.A., M.Div. Marquette University, 2009 This study examines the pervasive influence of post-exilic wisdom editors and writers in the shaping of the Psalter by analyzing the use of wisdom elements—vocabulary, themes, rhetorical devices, and parallels with other Ancient Near Eastern wisdom traditions. I begin with an analysis and critique of the most prominent authors on the subject of wisdom in the Psalter, and expand upon previous research as I propose that evidence of wisdom influence is found in psalm titles, the structure of the Psalter, and among the various genres of psalms. I find further evidence of wisdom influence in creation theology, as seen in Psalms 19, 33, 104, and 148, for which parallels are found in other A.N.E. wisdom texts. In essence, in its final form, the entire Psalter reveals the work of scribes and teachers associated with post-exilic wisdom traditions or schools associated with the temple. -

Psalm 74-77 73-83 Psalms of Asaph Or Family Members

Psalm 74-77 73-83 Psalms of Asaph or family members – LT Psalm 71-73 – 71 Psalm of Trust; 72 First Psalm of Solomon; 73 A Psalm of God’s Goodness (1st of the BOOK THREE and 2nd of Asaph (13 total)) Asaph was a Levite Worship Leader mentioned in 2 Kings 18 and 1 & 2 Chronicles Psalm 74 (A Plea for God’s Judgment) –A Contemplation or Maschil (used 13X) of Asaph, or, "A Psalm of Asaph, to give instruction." A time of great national oppression, after Shishak attacks Judah (1 King 14:25) 926 BC or after captivity by Nebuchadnezzar (2 Kings 24) 587 BC God is faithful - Looks at the present condition, refers back to the past (and God’s faithfulness) and looks out to the future of God’s remedy. Similar to Habakkuk 3 Prayers Vv1-3 – “sheep” Prayer 1 - Supplication 1. “Why” have you allowed this – “cast us off forever” not possible 2. “Remember” - “congregation”/“tribe of Your inheritance” “purchased”/“redeemed” – As if God can “forget” 3. “Lift up Your feet” – a plea for God to “return” 4. “Just because you can't see or imagine a good reason why God might allow something to happen it does not mean there can't be one.” – Tim Keller – God is always in control 5. Current times Vv4-9 “Your enemies” and “They” (6X) 1. Destruction, defilement, disaster, desolation 2. The enemies of God will always try to attack the people of God by natural means a. But we fight a “supernatural” battle – Eph. 6:12-13 Vv10-11 – 3 Questions “How long” and “Why” don’t you used your “Right hand”Prayer 2 – Supplication/Entreaty Vv12-17 – Remembering the past of God’s faithfulness – God then “You” 7X 1. -

Fr. Lazarus Moore the Septuagint Psalms in English

THE PSALTER Second printing Revised PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE DIOCESAN PRESS, MADRAS — 1971. (First edition, 1966) (Translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore) INDEX OF TITLES Psalm The Two Ways: Tree or Dust .......................................................................................... 1 The Messianic Drama: Warnings to Rulers and Nations ........................................... 2 A Psalm of David; when he fled from His Son Absalom ........................................... 3 An Evening Prayer of Trust in God............................................................................... 4 A Morning Prayer for Guidance .................................................................................... 5 A Cry in Anguish of Body and Soul.............................................................................. 6 God the Just Judge Strong and Patient.......................................................................... 7 The Greatness of God and His Love for Men............................................................... 8 Call to Make God Known to the Nations ..................................................................... 9 An Act of Trust ............................................................................................................... 10 The Safety of the Poor and Needy ............................................................................... 11 My Heart Rejoices in Thy Salvation ............................................................................ 12 Unbelief Leads to Universal