PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY Made Simple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

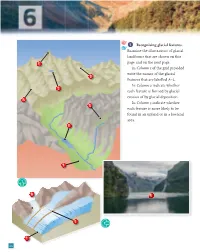

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

VACATION LAND the National Forests in Oregon

VACATION LAND The National Forests in Oregon High up in the mountains, where the timber is scarce and stunted and the only means of transportation is by horseback United States Department of Agriculture::Forest Service 1919 WELCOME TO THE ATIONAL PORESTS U.S.DEPARTVENT OFAGRICULTURE FOREST SIEIRVICE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT CIRCULAR 4 Contribution from the Forest Service HENRY S. GRAVES. Forester DIRECTORY OF NATIONAL FORESTS IN OREGON. George H. Cecil, District Forester. District Office, Post Office Building, Portland, Oreg. NATIONAL FOREST. FOREST SUPERVISOR. HEADQUARTERS. Cascade C. R. Seitz Eugene, Oreg. 2- Crater H B Rankin Medford, Oreg. Deschutes N. G. Jacobson Bend, Oreg. H Fremont...... Gilbert D. Brown Lakeview, Oreg. -Maiheur Cy J. Bingham John Day, Oreg. L-Milaam R. M. Evans.... Baker, Oreg. - Ochoco.. V. V. Harpham Prineville, Oreg. Oregon H. Sherrard...... Portland, Oreg. Santiam C. C. Hall.. Albany, Oreg. -Siskiyou.... N. F. Macduff Grants Pass, Oreg. Siuslaw R. S. Shelley Eugene, Oreg. \-Umati1la W. W. Cryder Pendleton, Oreg. 13 .Umpqua C. Bartrum Roseburg, Oreg. j Wallowa H. W. Harris Wallowa, Oreg. S'Wenaha J. C. Kulins Walla Walla, Wash. l,Whitman R. M. Evans.... Baker, Oreg. The view on page s of the cover is a reprodtction from a photograph of Mount Jefferson, Sautiam National Forest, showing forest and snow peak. THE NATIONAL VACATION 1 ANDESTS IN OREGON AN IDEAL VACATION LAND HEN, tired of the daily grind, you say to yourself, "I need a vacation," your first thought is to get away from civili- zation and its trammels.Your next is to find interest- ing and health-giving recreation.In the National For- ests in Oregon you may find both, and much besides. -

Glaciers and Glacial Erosional Landforms

GLACIERS AND GLACIAL EROSIONAL LANDFORMS Dr. NANDINI CHATTERJEE Associate Professor Department of Geography Taki Govt College Taki, North 24 Parganas, West Bengal Part I Geography Honours Paper I Group B -Geomorphology Topic 5- Development of Landforms GLACIER AND ICE CAPS Glacier is an extended mass of ice formed from snow falling and accumulating over the years and moving very slowly, either descending from high mountains, as in valley glaciers, or moving outward from centers of accumulation, as in continental glaciers. • Ice Cap - less than 50,000 km2. • Ice Sheet - cover major portion of a continent. • Ice thicker than topography. • Ice flows in direction of slope of the glacier. • Greenland and Antarctica - 3000 to 4000 m thick (10 - 13 thousand feet or 1.5 to 2 miles!) FORMATION AND MOVEMENT OF GLACIERS • Glaciers begin to form when snow remains Once the glacier becomes heavy enough, it in the same area year-round, where starts to move. There are two types of enough snow accumulates to transform glacial movement, and most glacial into ice. Each year, new layers of snow bury movement is a mixture of both: and compress the previous layers. This Internal deformation, or strain, in glacier compression forces the snow to re- ice is a response to shear stresses arising crystallize, forming grains similar in size and from the weight of the ice (ice thickness) shape to grains of sugar. Gradually the and the degree of slope of the glacier grains grow larger and the air pockets surface. This is the slow creep of ice due to between the grains get smaller, causing the slippage within and between the ice snow to slowly compact and increase in crystals. -

GLACIATION in SNOWDONIA by Paul Sheppard

GeoActiveGeoActive 350 OnlineOnline GLACIATION IN SNOWDONIA by Paul Sheppard This unit can be used These remnants of formerly much higher mountains have since been independently or in Conwy conjunction with OS 1:50,000 eroded into what is seen today. The Bangor mountains of Snowdonia have map sheet 115. N Caernarfon Llanrwst been changed as a result of aerial Llanberis Capel Curig Snowdon Betws y Coed (climatic) and fluvial (water) HE SNOWDONIA OR ERYRI (Yr Wyddfa) Beddgelert Blaenau erosion that always act upon a NATIONAL PARK, established Ffestiniog T Porthmadog landscape, but in more recent SNOWDONIA Y Bala in 1951, was the third National NATIONAL Harlech geological times the effects of ice PARK Park to be established in England have had a major impact upon the and Wales following the 1949 Barmouth Abermaw Dolgellau actual land surface. National Parks and Access to the Cadair Countryside Act (Figure 1). It Idris Tywyn 2 Machynlleth Glaciation covers an area of 2,171 km (838 Aberdyfi 0 25 km square miles) of North Wales and Ice ages have been common in the British Isles and northern Europe, encompasses the Carneddau and Figure 1: Snowdonia National Park Glyderau mountain ranges. It also with 40 having been identified by includes the highest mountain in important to look first at the geologists and geomorphologists. England and Wales, with Mount geological origins of the area, as The most recent of these saw Snowdon (Yr Wyddfa in Welsh) this provides the foundation upon Snowdonia covered with ice as reaching a height of 1,085 metres which ice can act. -

Glacial Features Explained

John Muir, Earth - Planet, Universe: Pupil Activity Support Notes Glacial features explained Glaciers The snow which forms temperate glaciers is subject to repeated freezing and thawing, which changes it into a form of granular ice called névé. Under the pressure of the layers of ice and snow above it, this granular ice fuses into denser firn. Over a period of years, layers of firn undergo further compaction and become glacial ice. The lower layers of glacial ice flow and deform plastically under the pressure, allowing the glacier as a whole to move slowly like a viscous fluid. Glaciers usually flow down a slope, although they do not need a surface slope to flow, as they can be driven by the continuing accumulation of new snow at their source, creating thicker ice and a surface slope. The upper layers of glaciers are more brittle, and often form deep cracks known as crevasses as they move. Erosion Rocks and sediments are added to glaciers through various processes. Glaciers erode the terrain principally through two methods: abrasion and plucking. As the glacier flows over the bedrock's fractured surface, it softens and lifts blocks of rock that are brought into the ice. This process is known as plucking, and it is produced when sub-glacial water penetrates the fractures and the subsequent freezing expansion separates them from the bedrock. When the water expands, it acts as a lever that loosens the rock by lifting it. This way, sediments of all sizes become part of the glacier's load. Abrasion occurs when the ice and the load of rock fragments slide over the bedrock and function as sandpaper that smooths and polishes the surface situated below. -

Mountain Glaciers

Mountain Glaciers By Marcus Arnold, James Clayton, Yogesh Karyakarte, Josianne Lalande Index 1. Introduction: ....................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Purpose of study: ................................................................................................................................ 4 3. Formation of a glacier: ........................................................................................................................ 4 Glacial Landforms/Geomorphological Structures: .................................................................................. 5 4. Mountain glacier landsystem: ........................................................................................................... 10 Plateau ice field..................................................................................................................................... 10 Glaciated valley systems ....................................................................................................................... 11 Trimlines and weathering zones ........................................................................................................... 12 Mountain ice field landsystem .............................................................................................................. 13 5. Mass Balance of Mountain Glaciers:- ................................................................................................ 13 Mass balance -

Mountain Glaciers

Mountain Glaciers Glaciology (JAR609G) Content • Where are they located… • How they have formed.. • Mountain glacier landsystem.. • Mass balance.. • Retreat.. • Effect on Human beings.. • Some issues regarding mountain glaciers.. Locations of mountain glacier - (Shape file = WGI- 2012, s/w: ArcGIS 9.2) Global distribution and surface area of glaciers (excluding the Greenland and Antarctic). Glaciers are divided into 100 regions ( shown in solid bars ); each region may represent one or many individual glaciers (Z. Zuo and J. Oerlemans, 1997) Why? • Hundreds of millions of people, particularly in Asia and South America, are residing in glacierized river basins. • Water for agriculture, industries and hydroelectricity power plants. • Mountain glaciers are highly sensitive to climate change (Hoelzle et al. 2003) • Quantitative relationship between climate change and glacier fluctuations Formation factors • High Elevation • Cool Temperatures • Winter’s snow does not melt entirely • Annual average temperature at or below 0°C • Solar radiation • Earth’s axis tilt and Solar Rotation • Mass Balance • Latitude Altitude vs Latitude • Snow-Line • 4500m at Equator • Up to 5700m at Tropics of Capricorn & Cancer • Around 3000m in NZ, parts of South America and North America and Europe • Gradually falls to sea-level at the poles Other factorsOther Factors Other factors include: • Aridity • Distance from Coastline • Diurnal Temperature Ranges Glacier formationGlacier Formation Assuming favourable conditions are met: • More snow accumulated = more pressure -

Glacial and Periglacial Environments

Glacial and Periglacial Environments Glacier classification: • Glacier: ➢ Large mass of ice resting on land or floating as an ice shelf in the sea adjacent to land • Form by accumulation of snow that recrystallizes under its weight • 2 general classifications of glaciers: ➢ Alpine ▪ Cirque ▪ Valley ➢ Ice sheet or Ice Cap Alpine glaciers: • Form within mountain ranges formation in snowfield confined to bowl shaped recess- cirque ➢ Main source are cirques • Cirque glacier Cirque glaciers: • Can study in the past landscapes ➢ Eg: past accumulations of ice had eroded out huge ‘bowl’ shaped areas Valley glacier: • Several cirque glaciers may feed valley glaciers ➢ Formed when cirque glaciers come together Ice caps and Ice Sheets: • A broad ice sheet resting on a plain or plateau and spreading outward from a central region of accumulation. • Huge plates of ice • Antarctica and Greenland • Antarctica = 92% of glacial ice • Present day Greenland and Antarctic Ice sheets • European ice sheet at last glacial ➢ Maximum around 20 ky ago when sea ➢ level was around 125 m lower than today Putting this into context: • Glacier ice sheets store masses and masses of water • The ice sheets can be the depth of Everest Mass balance of a valley glacier: • Accumulation zone near the top/ source of the glacier, near the cirque • Ablation zone increases/ advances as the accumulation zone increases, until an equilibrium is reached in which the accumulation zone is equal to the ablation zone ➢ Temperature may change which would alter the balance between accumulation/ ablation eg: ablation may retreat with increased temperatures and so the accumulation would be greater than the ablation zone. -

Glacier National Park

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR BULLETIN 600 THE GLACIER NATIONAL PARK A POPULAR GUIDE TO ITS GEOLOGY AND SCENERY BY iVIARIUS R. CAMPBELL WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1914 CONTENTS. Page. Introduction.............................................................. 5 General physical features of the park....................................... 6. Origin of the topographic forms ........'............................*........ 9 Conditions when the rocks were laid down............'.................. 9 Rocks uplifted and faulted............................................. 10 The uplifted mass carved by water...................................... 13 The uplifted mass modified by glacial ice............................... 14 The surface features....................................................... 15 Two Medicine Valley................................................... 16 Cut Bank Valley....................................................... 18 Red Eagle Valley...................................................... 20 St. Mary Valley....................................................... 22 Boulder Valley....................................................... 26 Swiftcurrent Valley................................................... 27 Kennedy Valley...................................................... 32 Belly River valley.................................................... 33 Little Kootenai Valley................................................ 36 McDonald Valley...................................................... -

Hiking Rocks! Seattle's Hiking DJ Geology on Trail

Epic Trails in the Glacier Peak Wilderness A Publication of Washington Trails AssociationWin | wta.orga New TENT! Details Inside! Hiking Rocks! Seattle's Hiking DJ Geology on Trail Wilderness Stewardship Protecting Your Trail Tech Shooting Macro Photos Jul+Aug 2014 Jul+Aug 2014 NW Explorer Hiking Rocks A geologic guide to identifying the glacial and volcanic landscapes on Washington’s trails. » p.20 Bob Rivers: Seattle’s Hiking DJ How the popular radio host started in broadcasting, and why he chose the Seattle area to settle. » p.26 Welcome Back Wolverines Almost driven to extinction in Washington, these feisty creatures are on the rebound. » p.30 NW Weekend » The Mountain Loop Explore the hiking, camping and area history between 20 Darrington and Granite Falls. » p.38 WIN A NEW TENT! News+Views August is hiking month! See how Suiattle River Road Reopening this Fall » p.9 you can win a new tent from NEMO “Lightning Bill” Moves to Leecher Lookout » p.10 or The North Face, then hit the trails! Enchanted Valley Chalet May Be Moved » p.11 » p.18 & 33 WTA at Work Trail Work » Road to Recovery on Boulder River Coming together where the work is needed. » p.12 Action for Trails » The Legacy of Trails How to identify different kinds of trails. »p.16 26 Trail Mix Gear Closet » Protect Your Tech on Trail Items for keeping electronics safe and useful. » p.42 Camera Bag » Marvelous Macro Capturing those up-close wildflower shots. »p.47 Bookshelf » Dirt Work by Christine Byl One woman’s story of trail work in Montana. -

Higher Geography Physical Environments Lithosphere

Higher Geography Physical Environments Lithosphere 1 Glaciated Landscapes Glacial History About every 200 million years the Earth experiences a major period of ice activity - an ice age. The most recent of these started about 2 million years ago and finished about 10,000 years ago. An ice age consists of glacials (cold periods ) separated by interglacials (warmer periods). About 30% of the world was covered by glacial ice when the last ice age was at its maximum. The UK was covered by ice between 1-3km thick as far south as a line from London to Bristol. Causes of Glaciation There are many theories as to the cause of glaciations: 1. Milankovitch cycle – changes in incoming solar radiation due to changes in orbit, tilt and position in space. 2. Variations in sunspot activity 3. Changes in the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere 4. Changes in the movement of the ocean currents 5. Periods of extreme volcanic activity which put huge amounts of ash into the atmosphere Formation of Glaciers During the onset of a glaciation, more and more precipitation falls as snow In addition, less and less snow melts each summer so that successive layers of snow gradually build up until there is a year-round snow cover in more and more places. As snow becomes more compacted, the air is driven out and density increases. Eventually, this process forms neve or firn (compacted snow). After 20-40 years the firn will turn into glacial ice which contains little air Glacial ice can begin to flow downhill under the influence of gravity as a glacier 2 Cross Profile of a Glacier Glaciers, like rivers, behave as a system with inputs, outputs, stores and transfers. -

2002-2003 North Cascades National Park Service Complex the Natural Resource Challenge R I He Popularity of National Parks Has Continued to A

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Notes 2002-2003 North Cascades National Park Service Complex The Natural Resource Challenge r I he popularity of National Parks has continued to A. grow since the U.S. Congress established Yellowstone, the first national park, in 1872. The 385 parks in the National Park System draw millions every year who come to experience the outdoors in spectacular settings or to learn about historic events where they happened. In the great scenic parks such as North Cascades people can recover from the stre s s of face-paced lives and reconnect with nature through camping, hiking, climbing, studying natural history and other activities. From the moment of Yellowstone's establishment, there have also been people who saw national parks as important for science. As world population and related developmentincreases, the scientific value of protected areas such as North Cascades National Park becomes increasingly evident. This fact combined with the great gaps in the National Park Service's knowledge of just what natural resources are in the parks has led in recent years to a significant change of direction for the agency. Without much more complete knowledge of the plants and animals in the national parks, the geology of these Rugged Mount Shuksan stands tall and white with snow beyond Picture Lake. Photo: Robert Morgan special places, and the ecological processes tying all these natural elements together, park managers cannot The North Cascades: a unique and treasured ecosystem be certain that they are adequately protecting the parks. ie rugged landscape of North Cascades National To know if the park is being adequately TPark is home to a unique collection of plants, protected, the National Park Service must assess its animals, natural processes, and cultural resources.