Edexcel AS and a Level Geography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ice on the Rocks: a Glacier Shapes the Land

Title Advance Preparation Ice on the Rocks: A Glacier Shapes the 1. Place rocks and sand in each bowl and add Land 2.5 cm of water. Allow the sand to settle, and freeze the contents solid. Later, add water until Investigative Question the bowls are nearly full and again freeze What are glaciers and how did they change the solid. These are the "glaciers" for part 1. landscape of Illinois? 2. Assemble the other materials. You may wish to do parts 1 and 3 in a laboratory setting Overview or out-of-doors because these activities are Students learn how glaciers, through abrasion, likely to be messy. transportation, and deposition, change the 3. Copy the student pages. surfaces over which they flow. Introducing the Activity Objective Hold up a square, normal-sized ice cube. Next Students conduct simulations and demonstrate to it hold up a toothpick that is as tall as the what a glacier does and how it can change the cube is thick. Ask students to picture the tallest landscape. building in Chicago, the Sears Tower. If the toothpick represents the Sears Tower, the ice Materials cube represents a glacier. The Sears Tower is Introductory activity: an ice cube and a about as tall as a glacier was thick! That was toothpick. the Wisconsinan glacier that was over 400 Part 1. For each group of five students: two meters thick and covered what is now the city plastic 1- or 2-qt. bowls; several small, of Chicago! irregularly shaped rocks or pebbles; a handful of coarse sand; a common, unglazed brick or a Procedure masonry brick (washed and cleaned); several Part 1 flat paving stones (limestone); water; access to 1. -

Basal Control of Supraglacial Meltwater Catchments on the Greenland Ice Sheet

The Cryosphere, 12, 3383–3407, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-12-3383-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Basal control of supraglacial meltwater catchments on the Greenland Ice Sheet Josh Crozier1, Leif Karlstrom1, and Kang Yang2,3 1University of Oregon Department of Earth Sciences, Eugene, Oregon, USA 2School of Geography and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China 3Joint Center for Global Change Studies, Beijing 100875, China Correspondence: Josh Crozier ([email protected]) Received: 5 April 2018 – Discussion started: 17 May 2018 Revised: 13 October 2018 – Accepted: 15 October 2018 – Published: 29 October 2018 Abstract. Ice surface topography controls the routing of sur- sliding regimes. Predicted changes to subglacial hydraulic face meltwater generated in the ablation zones of glaciers and flow pathways directly caused by changing ice surface to- ice sheets. Meltwater routing is a direct source of ice mass pography are subtle, but temporal changes in basal sliding or loss as well as a primary influence on subglacial hydrology ice thickness have potentially significant influences on IDC and basal sliding of the ice sheet. Although the processes spatial distribution. We suggest that changes to IDC size and that determine ice sheet topography at the largest scales are number density could affect subglacial hydrology primarily known, controls on the topographic features that influence by dispersing the englacial–subglacial input of surface melt- meltwater routing at supraglacial internally drained catch- water. ment (IDC) scales ( < 10s of km) are less well constrained. Here we examine the effects of two processes on ice sheet surface topography: transfer of bed topography to the surface of flowing ice and thermal–fluvial erosion by supraglacial 1 Introduction meltwater streams. -

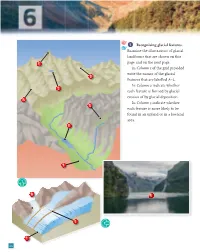

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Calving Processes and the Dynamics of Calving Glaciers ⁎ Douglas I

Earth-Science Reviews 82 (2007) 143–179 www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Calving processes and the dynamics of calving glaciers ⁎ Douglas I. Benn a,b, , Charles R. Warren a, Ruth H. Mottram a a School of Geography and Geosciences, University of St Andrews, KY16 9AL, UK b The University Centre in Svalbard, PO Box 156, N-9171 Longyearbyen, Norway Received 26 October 2006; accepted 13 February 2007 Available online 27 February 2007 Abstract Calving of icebergs is an important component of mass loss from the polar ice sheets and glaciers in many parts of the world. Calving rates can increase dramatically in response to increases in velocity and/or retreat of the glacier margin, with important implications for sea level change. Despite their importance, calving and related dynamic processes are poorly represented in the current generation of ice sheet models. This is largely because understanding the ‘calving problem’ involves several other long-standing problems in glaciology, combined with the difficulties and dangers of field data collection. In this paper, we systematically review different aspects of the calving problem, and outline a new framework for representing calving processes in ice sheet models. We define a hierarchy of calving processes, to distinguish those that exert a fundamental control on the position of the ice margin from more localised processes responsible for individual calving events. The first-order control on calving is the strain rate arising from spatial variations in velocity (particularly sliding speed), which determines the location and depth of surface crevasses. Superimposed on this first-order process are second-order processes that can further erode the ice margin. -

Seismic Model Report.Pdf

Scientific Report GEFSC Loan 925 The Character and Extent of subglacial Deformation and its Links to Glacier Dynamics in the Tarfala Basin, northern Sweden Jeffrey Evans, David Graham, and Joseph Pomeroy Polar and Alpine Research Group, Loughborough University ABSTRACT A pilot passive seismology experiment was conducted across the main overdeepening of Storglaciaren in the Tarfala Basin, northern Sweden, in July 2010, to see whether basal microseismic waveforms could be detected beneath a small polythermal arctic glacier and to investigate the spatial and temporal distribution of such waveforms in relation to known glacier flow dynamics. The high ablation rate made it difficult to keep geophones buried and well- coupled to the glacier during the experiment and reduced the number of days of good quality data collection. Event counts and the subsequent characterisation of typical and atypical waveforms showed that the dominant waveforms detected were from near-surface events such as crevassing. Although basal sliding is known to occur in the overdeepening, no convincing examples of basal waveforms were detected, which suggests basal microseismic signals are rare or difficult to detect beneath polythermal glaciers like Storglaciaren, a finding that is consistent with results from alpine glaciers in Switzerland. The data- set could prove useful to glaciologists interested in the dynamics of near-surface events such as crevassing, the opening and closing of englacial water conduits, or temporal and spatial changes in the glacier’s stress field. Background Smith (2006) found that pervasive soft-bed deformation characterised parts of the Rutland Ice Stream in West Antarctica and produced 6 times fewer basal microseismic signals than regions where basal sliding or stick slip movement dominated. -

What Glaciers Are Telling Us About Earth's Changing Climate

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | The Cryosphere Discuss., 8, 3475–3491, 2014 www.the-cryosphere-discuss.net/8/3475/2014/ doi:10.5194/tcd-8-3475-2014 TCD © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 8, 3475–3491, 2014 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal The Cryosphere (TC). What glaciers are Please refer to the corresponding final paper in TC if available. telling us about Earth’s changing What glaciers are telling us about Earth’s climate changing climate W. Tangborn and M. Mosteller W. Tangborn1 and M. Mosteller2 1HyMet Inc., Vashon Island, WA, USA Title Page 2 Vashon IT, Vashon Island, WA, USA Abstract Introduction Received: 12 June 2014 – Accepted: 24 June 2014 – Published: 1 July 2014 Conclusions References Correspondence to: W. Tangborn ([email protected]) and Tables Figures M. Mosteller ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. J I J I Back Close Full Screen / Esc Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 3475 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract TCD A glacier monitoring system has been developed to systematically observe and docu- ment changes in the size and extent of a representative selection of the world’s 160 000 8, 3475–3491, 2014 mountain glaciers (entitled the PTAAGMB Project). Its purpose is to assess the impact 5 of climate change on human societies by applying an established relationship between What glaciers are glacier ablation and global temperatures. Two sub-systems were developed to accom- telling us about plish this goal: (1) a mass balance model that produces daily and annual glacier bal- Earth’s changing ances using routine meteorological observations, (2) a program that uses Google Maps climate to display satellite images of glaciers and the graphical results produced by the glacier 10 balance model. -

EVIDENCE of POSSIBLE GLACIAL FEATURES on TITAN. L. E. Robshaw1, J

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIX (2008) 2087.pdf EVIDENCE OF POSSIBLE GLACIAL FEATURES ON TITAN. L. E. Robshaw1, J. S. Kargel2, R. M. C. Lopes3, K. L. Mitchell3, L. Wilson1 and the Cassini RADAR team, 1Lancaster University, Environmental Sci. Dept., Lancaster, UK, 2Dept. of Hydrology and Water Resources, University of Arizona, 3Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasa- dena, CA 91109. Introduction: It has been suggested previously Figure 1 shows coastline that has at least superficial [e.g. 1] that solid hydrocarbons might condense in Ti- similarities with the coast of Norway and other fjord tan’s atmosphere, snow down onto the surface and areas. There are many, roughly parallel, steep-sided form glacier-like features, but no strong evidence has valleys, often with rounded heads. Most are approxi- been obtained. The high northern latitudes imaged in mately the same size as the valleys on the Norwegian the SAR swath obtained during Cassini’s T25 fly-by off-shore islands. (figure 1, top), however, exhibit morphological simi- There also appears to be some similarity between larities with glacial landscapes on the Earth, particu- the areas that arrows b & c point to (fig. 1, area shown larly the coast of Norway (figure 1, bottom). Several also in close-up in fig. 2, top) and the islands of the areas exhibit fjord-like valleys, with possible terminal Outer Lands (Fig. 2, bottom), a terminal moraine ar- moraine archipelagos, and further inland are dry val- chipelagic region off the southern coast of New Eng- leys, reminiscent of glacial scouring. Other noted fea- land. tures may be a ribbon lake and an Arête, both the result of glacial erosion. -

Surface Mass Balance of Davies Dome and Whisky Glacier on James Ross Island, North-Eastern Antarctic Peninsula, Based on Different Volume-Mass Conversion Approaches

CZECH POLAR REPORTS 9 (1): 1-12, 2019 Surface mass balance of Davies Dome and Whisky Glacier on James Ross Island, north-eastern Antarctic Peninsula, based on different volume-mass conversion approaches Zbyněk Engel1*, Filip Hrbáček2, Kamil Láska2, Daniel Nývlt2, Zdeněk Stachoň2 1Charles University, Faculty of Science, Department of Physical Geography and Geoecology, Albertov 6, 128 43 Praha, Czech Republic 2Masaryk University, Faculty of Science, Department of Geography, Kotlářská 2, 611 37 Brno, Czech Republic Abstract This study presents surface mass balance of two small glaciers on James Ross Island calculated using constant and zonally-variable conversion factors. The density of 500 and 900 kg·m–3 adopted for snow in the accumulation area and ice in the ablation area, respectively, provides lower mass balance values that better fit to the glaciological records from glaciers on Vega Island and South Shetland Islands. The difference be- tween the cumulative surface mass balance values based on constant (1.23 ± 0.44 m w.e.) and zonally-variable density (0.57 ± 0.67 m w.e.) is higher for Whisky Glacier where a total mass gain was observed over the period 2009–2015. The cumulative sur- face mass balance values are 0.46 ± 0.36 and 0.11 ± 0.37 m w.e. for Davies Dome, which experienced lower mass gain over the same period. The conversion approach does not affect much the spatial distribution of surface mass balance on glaciers, equilibrium line altitude and accumulation-area ratio. The pattern of the surface mass balance is almost identical in the ablation zone and very similar in the accumulation zone, where the constant conversion factor yields higher surface mass balance values. -

Mass-Balance Reconstruction for Kahiltna Glacier, Alaska

Journal of Glaciology (2018), Page 1 of 14 doi: 10.1017/jog.2017.80 © The Author(s) 2018. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The challenge of monitoring glaciers with extreme altitudinal range: mass-balance reconstruction for Kahiltna Glacier, Alaska JOANNA C. YOUNG,1 ANTHONY ARENDT,1,2 REGINE HOCK,1,3 ERIN PETTIT4 1Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK, USA 2Applied Physics Laboratory, Polar Science Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 3Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden 4Department of Geosciences, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, USA Correspondence: Joanna C. Young <[email protected]> ABSTRACT. Glaciers spanning large altitudinal ranges often experience different climatic regimes with elevation, creating challenges in acquiring mass-balance and climate observations that represent the entire glacier. We use mixed methods to reconstruct the 1991–2014 mass balance of the Kahiltna Glacier in Alaska, a large (503 km2) glacier with one of the greatest elevation ranges globally (264– 6108 m a.s.l.). We calibrate an enhanced temperature index model to glacier-wide mass balances from repeat laser altimetry and point observations, finding a mean net mass-balance rate of −0.74 − mw.e. a 1(±σ = 0.04, std dev. of the best-performing model simulations). Results are validated against mass changes from NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites, a novel approach at the individual glacier scale. -

Hiking Trails

0a3 trail 0d4 trail 0d5 trail 0rdtr1 trail 14 mile connector trail 1906 trail 1a1 trail 1a2 trail 1a3 trail 1b1 trail 1c1 trail 1c2 trail 1c4 trail 1c5 trail 1f1 trail 1f2 trail 1g2 trail 1g3 trail 1g4 trail 1g5 trail 1r1 trail 1r2 trail 1r3 trail 1y1 trail 1y2 trail 1y4 trail 1y5 trail 1y7 trail 1y8 trail 1y9 trail 20 odd peak trail 201 alternate trail 25 mile creek trail 2b1 trail 2c1 trail 2c3 trail 2h1 trail 2h2 trail 2h4 trail 2h5 trail 2h6 trail 2h7 trail 2h8 trail 2h9 trail 2s1 trail 2s2 trail 2s3 trail 2s4 trail 2s6 trail 3c2 trail 3c3 trail 3c4 trail 3f1 trail 3f2 trail 3l1 trail 3l2 trail 3l3 trail 3l4 trail 3l6 trail 3l7 trail 3l9 trail 3m1 trail 3m2 trail 3m4 trail 3m5 trail 3m6 trail 3m7 trail 3p1 trail 3p2 trail 3p3 trail 3p4 trail 3p5 trail 3t1 trail 3t2 trail 3t3 trail 3u1 trail 3u2 trail 3u3 trail 3u4 trail 46 creek trail 4b4 trail 4c1 trail 4d1 trail 4d2 trail 4d3 trail 4e1 trail 4e2 trail 4e3 trail 4e4 trail 4f1 trail 4g2 trail 4g3 trail 4g4 trail 4g5 trail 4g6 trail 4m2 trail 4p1 trail 4r1 trail 4w1 trail 4w2 trail 4w3 trail 5b1 trail 5b2 trail 5e1 trail 5e3 trail 5e4 trail 5e6 trail 5e7 trail 5e8 trail 5e9 trail 5l2 trail 6a2 trail 6a3 trail 6a4 trail 6b1 trail 6b2 trail 6b4 trail 6c1 trail 6c2 trail 6c3 trail 6d1 trail 6d3 trail 6d5 trail 6d6 trail 6d7 trail 6d8 trail 6m3 trail 6m4 trail 6m7 trail 6y2 trail 6y4 trail 6y5 trail 6y6 trail 7g1 trail 7g2 trail 8b1 trail 8b2 trail 8b3 trail 8b4 trail 8b5 trail 8c1 trail 8c2 trail 8c4 trail 8c5 trail 8c6 trail 8c9 trail 8d2 trail 8g1 trail 8h1 trail 8h2 trail 8h3 trail -

Diagnosing Ice Sheet Grounding Line Stability from Landform Morphology

Supplementary Information: Diagnosing ice sheet grounding line stability from landform morphology Lauren M. Simkins1, Sarah L. Greenwood2, John B. Anderson1 5 1 Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, Rice University, Houston, TX 77005, USA 2 Department of Geological Sciences, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden *Equal contributions Correspondence to: Lauren M. Simkins ([email protected]) 1 Supplementary Methods 10 Grounding line landforms were mapped into three groups including grounding zone wedges, recessional moraines, and crevasse squeeze ridges in ArcGIS using NBP1502A and legacy multibeam data collected aboard the RVIB Nathaniel B. Palmer. Landforms displaying asymmetric morphologies and smeared surficial appearances resulting from relatively broad stoss widths (compared to lee widths) were interpreted as grounding zone wedges, whereas symmetric, quasi-linear landforms with regular spacing were interpreted as recessional moraines. Identified landforms are within fields of like 15 landforms. Within one field of recessional moraines, erratically shaped landforms with variable orientations and irregular amplitudes that are generally greater than that of the recessional moraines were interpreted as crevasse squeeze ridges. Morphometrics for grounding zone wedges and recessional moraines were generated from transects across landforms using the ‘findpeaks’ function in Matlab. Measured properties include (1) amplitude measured from landform crestlines, (2) width in the along-flow direction, (3) spacing between adjacent landform peaks, and (4) asymmetry measured as the ratio of offset 20 between the peak location and the half width point, where a landform with a value of 0 has a peak directly above the half width point and is classified as symmetric and a landform with an asymmetry of 1 has a peak furthest from the half width point and displays the most pronounced asymmetry. -

Preventing Ice Dams

{Property} Preventing Ice Dams waterWhat CAU Recommends: Introduction > Clean rain gutters annually to Ice dams represent a costly (and potentially remove obstructions that can dangerous) hazard for property owners and block the flow of water from community associations. Even worse, once a the roof building has shown itself to be susceptible to ice > Inspect attic insulation and dams, it is more likely to keep developing them ventilation during future cold weather. > Install ice shields or other waterproof membranes The majority of ice dams form as a ridge of ice beneath the roof covering along a rain gutter and roof eave. As ice builds during roof replacement up, it creates an unintended dam that prevents projects melting snow from draining off of the roof. Some > Locate a contractor that can can be very easy to see, but others form around clear ice dams from your skylights, chimneys, and other features that make buildings them harder to detect from the ground. Need More Information? Whether they are visible or not, ice dams can Additional information relating cause significant damage to a building or unit. to ice dam prevention is That’s because water that pools up behind it can available from The Institute find its way under the roof and into the structure for Business and Home Safety and the interior of a home. It isn’t unusual for (www.disastersafety.org) or by ice dams to cause damage to insulation, wall contacting CAU’s Loss Control interiors, ceiling finishes, and trim. Exterior Department. damage to roofs, gutters, and spaces below an ice dam (like windows and landscaping) is also common.