Download the 2016 Projects for Peace Viewbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

88 of the Colami Games 11 1 3 Count Bout 21 Action Fighter 2 1941 12 4

Game List- 1 1 88 of the colami games 11 3 Count Bout 21 Action Fighter 2 1941 12 4 En Raya 22 Aero Fighters 3 1942 13 4-D Warriors 23 Aero Fighters 2 4 1943 14 64Th Street 24 Aero Fighters 3 5 1943 U 15 88games 25 After Burner II 6 1943Kai 16 A fighter 26 Agress 7 1944-The Loop Maste 17 A question and answer mystery27 detectiveAgress 8 1945KIII 18 ASO 28 Ah Eikou no Koshien 9 19XX 19 Acrobat Mission 29 Air Attack 10 2020 Baseball 20 Act-Fancer 30 Air Buster 31 Air Duel 41 Aliens 51 Aqua Jack 32 Airwolf 42 Aliens - Thanatos Encounter 52 Aquajack 33 Akuma-Jou Dracula 43 Alpha Mission II 53 Aquarium 34 Alex Kidd 44 Alpine Ski 54 Arabian Magic 35 Algo&Trinca 45 Altered Beast 55 Arbalester 36 Ali Baba 46 Ambush 56 Arcadia 37 Alien Challenge 47 Amidar 57 Argus 38 Alien Storm 48 Andro Dunos 58 Ark Zone Game 39 Alien Syndrome 49 Angel Kids 59 Arkanoid 40 Alien Vs Predator 50 Anteater 60 Arkanoid 2 61 Armed Police Batride 71 Asuka & Asuka 81 Azurian Attack 62 Armed Police Batrider 72 Asura Blade 82 B.C. Story 63 Armored Car 73 Asylum 83 B.C. Story 64 Armored Warriors 74 Athena 84 Back Street Soccer 65 Art Of Fighting 75 Atomic Point 85 Bad Lands 66 Art Of Fighting 2 76 Atomic Runner 86 Bad Omen 67 Art Of Fighting 3 77 Aurail 87 Bagman 68 Asterix 78 Avengers 88 Balloon Brothers 69 Asterix 1 79 Avenging Spirit 89 Bang Bang Ball 70 Astro Blaster 80 Aztarac 90 Bang Bang Busters 91 Bang Bead 101 Battle Circuit 111 Bells & Whistles 92 Bank Panic 102 Battle City 112 Beraboh Man 93 Baseball Stars 103 Battle Flip Shot 113 Berlin Wall 94 Baseball Stars -

Parar En Seco*

HECHOS/IDEAS WILLIAM OSPINA Parar en seco* En nada se conoce tanto el brío de un potro como en la capacidad de parar en seco. MONTAIGNE, Ensayos El gran malestar uando en el mes de marzo de 2016 los diarios mostraron que se había blanqueado la barrera coralina de Australia, Cmuchos en el mundo tuvimos la sensación de que la hora definitiva estaba llegando. Largo tiempo se creyó que el fin del mundo sería un solo evento catastrófico, una suerte de espectáculo cósmico como los que evoca Rafael Argullol en su admirable libro El fin del mundo como obra de arte. Lo que estamos empezando a ver más bien podría designarse como el Gran Malestar. No carecerá de catástrofes: las erupciones volcánicas desde Islandia hasta Indonesia, el continente de plástico del Pacífico, la desaparición de los hielos del Ártico, el peligro alarmante del derretimiento del permafrost de Siberia, que guarda frágilmente 5-20 pp. enero-marzo/2018 290 No. los mayores depósitos de metano del mundo, la muerte masiva de especies, como lo que se ha dado en llamar recientemente el Apocalipsis de las abejas, pero el actual calentamiento global, una evidencia cuyos diagramas nos alarman día a día en internet, * Este texto apareció originalmente Américas de las Casa como libro publicado en Barcelona puede no consistir en un mero aumento de temperaturas, sino en un por Navona Editorial en 2017. progresivo enrarecimiento de las condiciones de vida en el mundo. Revista 5 Lo sentimos con el clima, con veranos e raleza podría dar lugar a una súbita mutación inviernos cada vez más alterados, con el des- que vuelva a hacer de nosotros la más frágil plazamiento de los mapas vegetales, con la de las especies. -

51ST ANNUAL CONVENTION March 5–8, 2020 Boston, MA

Northeast Modern Language Association 51ST ANNUAL CONVENTION March 5–8, 2020 Boston, MA Local Host: Boston University Administrative Sponsor: University at Buffalo SUNY 1 BOARD OF DIRECTORS President Carole Salmon | University of Massachusetts Lowell First Vice President Brandi So | Department of Online Learning, Touro College and University System Second Vice President Bernadette Wegenstein | Johns Hopkins University Past President Simona Wright | The College of New Jersey American and Anglophone Studies Director Benjamin Railton | Fitchburg State University British and Anglophone Studies Director Elaine Savory | The New School Comparative Literature Director Katherine Sugg | Central Connecticut State University Creative Writing, Publishing, and Editing Director Abby Bardi | Prince George’s Community College Cultural Studies and Media Studies Director Maria Matz | University of Massachusetts Lowell French and Francophone Studies Director Olivier Le Blond | University of North Georgia German Studies Director Alexander Pichugin | Rutgers, State University of New Jersey Italian Studies Director Emanuela Pecchioli | University at Buffalo, SUNY Pedagogy and Professionalism Director Maria Plochocki | City University of New York Spanish and Portuguese Studies Director Victoria L. Ketz | La Salle University CAITY Caucus President and Representative Francisco Delgado | Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY Diversity Caucus Representative Susmita Roye | Delaware State University Graduate Student Caucus Representative Christian Ylagan | University -

November 23, 2015 Wrestling Observer Newsletter

1RYHPEHU:UHVWOLQJ2EVHUYHU1HZVOHWWHU+ROPGHIHDWV5RXVH\1LFN%RFNZLQNHOSDVVHVDZD\PRUH_:UHVWOLQJ2EVHUYHU)LJXUH)RXU2« RADIO ARCHIVE NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE THE BOARD NEWS NOVEMBER 23, 2015 WRESTLING OBSERVER NEWSLETTER: HOLM DEFEATS ROUSEY, NICK BOCKWINKEL PASSES AWAY, MORE BY OBSERVER STAFF | [email protected] | @WONF4W TWITTER FACEBOOK GOOGLE+ Wrestling Observer Newsletter PO Box 1228, Campbell, CA 95009-1228 ISSN10839593 November 23, 2015 UFC 193 PPV POLL RESULTS Thumbs up 149 (78.0%) Thumbs down 7 (03.7%) In the middle 35 (18.3%) BEST MATCH POLL Holly Holm vs. Ronda Rousey 131 Robert Whittaker vs. Urijah Hall 26 Jake Matthews vs. Akbarh Arreola 11 WORST MATCH POLL Jared Rosholt vs. Stefan Struve 137 Based on phone calls and e-mail to the Observer as of Tuesday, 11/17. The myth of the unbeatable fighter is just that, a myth. In what will go down as the single most memorable UFC fight in history, Ronda Rousey was not only defeated, but systematically destroyed by a fighter and a coaching staff that had spent years preparing for that night. On 2/28, Holly Holm and Ronda Rousey were the two co-headliners on a show at the Staples Center in Los Angeles. The idea was that Holm, a former world boxing champion, would impressively knock out Raquel Pennington, a .500 level fighter who was known for exchanging blows and not taking her down. Rousey was there to face Cat Zingano, a fight that was supposed to be the hardest one of her career. Holm looked unimpressive, barely squeaking by in a split decision. Rousey beat Zingano with an armbar in 14 seconds. -

Conservación De Vidrieras Históricas

Conservacion de vidrieras historicas Analisis y diagnostico de su deterioro. Restauracion. - •.' ; --- I ; :.. -' -- .......- . /" � --- � .:.:-- - -,, --- " Conservacion de vidrieras historicas Analisis y diagnostico de su deterioro. Restauracion. Aetas de la reunion Seminario organizado por The Getty Conservation Institute y la Universidad Internaeional Menendez y Pelayo, en eonjunto con el Instituto de Conservaeion y Restauraeion de Bienes Culturales Santander, Espana 4-8 de julio de 1994 Coordinadores Miguel Angel Corzo, The Getty Conservation Institute Nieves Valentin, Instituto del Patrimonio Historieo Espanol, Ministerio de Cultura THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE Los ANGELES Portada: Catedral de Leon. Detalle de la firma del arquitecto Juan Bautista Lazaro y del pintor Alberto Gonzales. Fotografiacortesi a de IPHE. Contraportada: Catedral de Leon. Otro detalle de la vidriera. Fotografiacortesia de IPHE. Miguel Angel Corzo, Coordinador Nieves Valentin, Coordinadora Helen Mauch!, Coordinadora de publicaci6n Fernando Cortes Pizano, Traductor JeffreyCohen, Diseiiadorgra fico de la serie Marquita Takei, Diseiiadoragra fica del libro Westland Graphics, Impresora Impreso en los Estados Unidos de America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 © por The J. Paul Getty Trust Todos los derechos reservados The Getty Conservation Institute trabaja internacionalmente para promover la apreciacion y conservacion del patrimonio cultural del mundo para el enriquecimiento y uso de las generaciones presentes y futuras. El Instituto es un programa operativo de The J. Paul Getty Trust. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conservacion de vidrieras historicas: analisis y diagnostico de su deterioro: restauracion / [semina rio organizado por The Getty Conservation Institute y la Universidad Internacional Menendez y Pelayo, en conjunto con el Instituto de Conservacion y Restauracion de Bienes Culturalesl; coordinadores de la conferencia, Miguel Angel Corzo, Nieves Valentin. -

3390 in 1 Games List

3390 in 1 Games List www.arcademultigamesales.co.uk Game Name Tekken 3 Tekken 2 Tekken Street Fighter Alpha 3 Street Fighter EX Bloody Roar 2 Mortal Kombat 4 Mortal Kombat 3 Mortal Kombat 2 Gear Fighter Dendoh Shiritsu Justice gakuen Turtledove (Chinese version) Super Capability War 2012 (US Edition) Tigger's Honey Hunt(U) Batman Beyond - Return of the Joker Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Dual Heroes Killer Instinct Gold Mace - The Dark Age War Gods WWF Attitude Tom and Jerry in Fists of Furry 1080 Snowboarding Big Mountain 2000 Air Boarder 64 Tony Hawk's Pro Skater Aero Gauge Carmageddon 64 Choro Q 64 Automobili Lamborghini Extreme-G Jeremy McGrath Supercross 2000 Mario Kart 64 San Francisco Rush - Extreme Racing V-Rally Edition 99 Wave Race 64 Wipeout 64 All Star Tennis '99 Centre Court Tennis Virtual Pool 64 NBA Live 99 Castlevania Castlevania: Legacy of 1 Darkness Army Men - Sarge's Heroes Blues Brothers 2000 Bomberman Hero Buck Bumble Bug's Life,A Bust A Move '99 Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Doraemon 2 - Nobita to Hikari no Shinden Gex 3 - Deep Cover Gecko Ms. Pac-Man Maze Madness O.D.T (Or Die Trying) Paperboy Rampage 2 - Universal Tour Super Mario 64 Toy Story 2 Aidyn Chronicles Charlie Blast's Territory Perfect Dark Star Fox 64 Star Soldier - Vanishing Earth Tsumi to Batsu - Hoshi no Keishousha Asteroids Hyper 64 Donkey Kong 64 Banjo-Kazooie The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time The King of Fighters '97 Practice The King of Fighters '98 Practice The King of Fighters '98 Combo Practice The King of Fighters -

EMBODYING MODERNITY in MEXIO: RACE, TECHNOLOGY, and the BODY in the MESTIZO STATE by Copyright © 2015 David S

EMBODYING MODERNITY IN MEXIO: RACE, TECHNOLOGY, AND THE BODY IN THE MESTIZO STATE By Copyright © 2015 David S. Dalton Submitted to the graduate degree program in Spanish and Portuguese and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson, Stuart A. Day ________________________________ Luciano Tosta ________________________________ Rafael Acosta ________________________________ Nicole Hodges Persley ________________________________ Jerry Hoeg Date Defended: May 11, 2015 ii The Dissertation Committee for David S. Dalton certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: EMBODYING MODERNITY IN MEXICO: RACE, TECHNOLOGY, AND THE BODY IN THE MESTIZO STATE ________________________________ Chairperson Stuart A. Day Date approved: May 11, 2015 iii ABSTRACT Mexico’s traumatic Revolution (1910-1917) attested to stark divisions that had existed in the country for many years. After the dust of the war settled, post-revolutionary leaders embarked on a nation-building project that aimed to assimilate the country’s diverse (particularly indigenous) population under the umbrella of official mestizaje (or an institutionalized mixed- race identity). Indigenous Mexican woud assimilate to the state by undergoing a project of “modernization,” which would entail industrial growth through the imposition of a market-based economy. One of the most remarkable aspects of this project of nation-building was the post- revolutionary government’s decision to use art to communicate official discourses of mestizaje. From the end of the Revolution until at least the 1970s, state officials funded cultural artists whose work buoyed official discourses that posited mixed-race identity as a key component of an authentically Mexican modernity. -

Title of Book/Magazine/Newspaper Author/Issue Datepublisher Information Her Info

TiTle of Book/Magazine/newspaper auThor/issue DaTepuBlisher inforMaTion her info. faciliT Decision DaTe censoreD appealeD uphelD/DenieD appeal DaTe fY # American Curves Winter 2012 magazine LCF censored September 27, 2012 Rifts Game Master Guide Kevin Siembieda book LCF censored June 16, 2014 …and the Truth Shall Set You Free David Icke David Icke book LCF censored October 5, 2018 10 magazine angel's pleasure fluid issue magazine TCF censored May 15, 2017 100 No-Equipment Workout Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 of the Most Beautiful Women in Painting Ed Rebo book HCF censored February 18, 2011 100 Things You Will Never Find Daniel Smith Quercus book LCF censored October 19, 2018 100 Things You're Not Supposed To Know Russ Kick Hampton Roads book HCF censored June 15, 2018 100 Ways to Win a Ten-Spot Comics Buyers Guide book HCF censored May 30, 2014 1000 Tattoos Carlton Book book EDCF censored March 18, 2015 yes yes 4/7/2015 FY 15-106 1000 Tattoos Ed Henk Schiffmacher book LCF censored December 3, 2007 101 Contradictions in the Bible book HCF censored October 9, 2017 101 Cult Movies Steven Jay Schneider book EDCF censored September 17, 2014 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genius Brad Graham & Kathy McGowan book HCF censored August 31, 2011 yes yes 9/27/2011 FY 12-009 110 Years of Broadway Shows, Stories & Stars: At this Theater Viagas & Botto Applause Theater & Cinema Books book LCF censored November 30, 2018 113 Minutes James Patterson Hachette books book -

Los Cuatro Jinetes Del Apocalipsis

Los cuatro jinetes del Apocalipsis Vicente Blasco Ibáñez Prólogo En julio de 1914 noté los primeros indicios de la próxima guerra europea, viniendo de Buenos Aires a las costas de Francia en el vapor alemán König Friedrich August. Era el mismo buque que figura en los primeros capítulos de esta obra. No quise cambiar ni desfigurar su nombre. Copias exactas del natural son también los personajes alemanes que aparecen en el principio de la novela. Los oí hablar con entusiasmo de la guerra preventiva y celebrar, con una copa de champaña en la mano, la posibilidad, cada vez más cierta, de que Alemania declarase la guerra, sin reparar en pretextos. ¡Y esto en medio del Océano, lejos de las grandes agrupaciones humanas, sin otra relación con el resto del planeta que las noticias intermitentes y confusas que podía recoger la telegrafía sin hilos del buque en aquel ambiente agitado por los mensajes ansiosos que cruzaban todos los pueblos!... Por eso sonrío con desprecio o me indigno siempre que oigo decir que Alemania no quiso la guerra y que los alemanes no estaban deseosos de llegar a ella cuanto antes. El primer capítulo de Los cuatro jinetes del Apocalipsis me lo proporcionó un viaje casual a bordo del último transatlántico germánico que tocó Francia. Viviendo semanas después en el París solitario de principios de septiembre de 1914, cuando se desarrolló la primera batalla del Marne y el Gobierno francés tuvo que trasladarse a Burdeos por medida de prudencia, al ambiente extraordinario de la gran ciudad me sugirió todo el resto de la presente novela. -

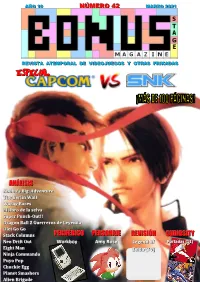

Capcom Vs SNK – SNK Vs Capcom Por Skullo

AAÑÑOO 1100 NNÚÚMMEERROO 4422 MMAARRZZOO 22002211 RREEVVIISSTTAA AATTEEMMPPOORRAALL DDEE VVIIDDEEOOJJUUEEGGOOSS YY OOTTRRAASS FFRRIIKKAADDAASS AANNÁÁLLIISSIISS AAbboobboo’’’ss BBiiigg AAddvveennttuurree TThhee B Beerrllliiinn WWaallllll WWaacckkyy RRaacceess EElll llliiibbrroo ddee lllaa sseelllvvaa SSuuppee rr PPuunncchh---OOuutt!!!!!! DDrraaggoonn BBaallllll ZZ GGuueerrrreerrooss ddee LLeeyyeennddaa DDiiieett GGoo GGoo SSttaacckk CCoollluummnnss PPEERRIIFFÉÉRRIICCOO PPEERRSSOONNAAJJEE RREEVVIISSIIÓÓNN CCUURRIIOOSSIITTYY Neo Drift Out Portadas (11) Neo Driifft Out WWoorrkkbbooyy AAmmyy RRoossee LLeeggeenndd ooff Portadas ((11)) EEiiigghhtt MMaann ZZeelllddaa ((TTVV)) NNiiinnjjjaa CCoommmmaannddoo PPuuyyoo PPoopp CChhuucckkiiiee EEgggg PPlllaanneett SSmmaasshheerrss AAllliiieenn BBrriiiggaaddee Número 42 – Marzo 2021 ÍNDICE Editorial por Skullo ..................................................03 Análisis Chuckie Egg por Skullo ................................................ 04 Planet Smashers por Skullo ....................................... 06 Alien Brigade por Skullo ............................................ 08 Berlin no Kabe – The Berlin Wall por Skullo .............. 11 Eight Man por Skullo................................................... 14 Diet Go Go por Skullo ................................................. 18 Ninja Commando por Skullo ............................................... 21 Stack Columns por Skullo .................................................... 24 El Libro de la Selva por Skullo .......................................... -

José Domingo Garzón Universidad Pedagógica Nacional

Pensamiento palabra y obra ISSN: 2011-804X Facultad de Bellas Artes Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Garzón Garzón, José Domingo In gold we trust o ¿qué demonios vamos a hacer?. Pequeña farsa fuera de todo contexto Pensamiento palabra y obra, núm. 19, 2018, Enero-Junio, pp. 126-145 Facultad de Bellas Artes Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=614164649010 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto 126 (pensamiento), (palabra)... Y oBra In Gold we Trust o ¿Qué demonios vamos a hacer? Pequeña farsa fuera de todo contexto 127 No. 19, enero-junio de 2018. pp. 126-145 Dramaturgia: José Domingo Garzón Garzón (obra) (pensamiento), (palabra)... Y oBra IN GOLD WE TRUST O ¿QUÉ DEMONIOS VAMOS A HACER? Pequeña farsa fuera de todo contexto Dramaturgia: José Domingo Garzón Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. Licenciatura en Artes Escénicas. Proceso autónomo de creación, 2014 Estudiantes: Diego Muñoz, Katherine Martínez, Samantha Gutiérrez … y obra 128 (pensamiento), (palabra)... Y oBra In Gold we Trust o ¿Qué demonios vamos a hacer? Pequeña farsa fuera de todo contexto 129 No. 19, enero-junio de 2018. pp. 126-145 Dramaturgia: José Domingo Garzón Garzón A manera de resumen. Procesos autónomos de creación Escenario: Un raído telón, rojo desteñido, chamuscado en algunos lados, grafitiado en otros, manchado, decadente… parece pared de universidad pública. Este quizá sea uno de los principales patrimonios de la Licenciatura en Artes Escénicas de la Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. -

Confessional Poetry of the 1970S from Argentina and the United States Julia Eva Leverone Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2016 A Daring Voice: Confessional Poetry of the 1970s from Argentina and the United States Julia Eva Leverone Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the American Literature Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Latin American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Leverone, Julia Eva, "A Daring Voice: Confessional Poetry of the 1970s from Argentina and the United States" (2016). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 811. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/811 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Program in Comparative Literature Dissertation Examination Committee: Ignacio Infante, Chair Mary Jo Bang Charles Hatfield Tabea Linhard Paul Michael Lützeler Elzbieta Sklodowska A Daring Voice: Confessional Poetry of the 1970s from Argentina and the United States by Julia Leverone A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial