Bojanala Platinum District Municipality Environmental Management Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zeerust Sub District of Ramotshere Moiloa Magisterial District Main

# # !C # ### # !C^# #!.C# # !C # # # # # # # # # ^!C# # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # ## # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # ## # # # # !C# # # # #!C# # # ## ^ ## # !C # # # # # ^ # # # # # # #!C # # # !C # # #^ # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C# ## # # # # # # !C# # !C # # # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # #!C# # # # # ## # # # # # # # ##!C # # ## # # # # # # # # # # !C### # # ## # ## # # # # # ## ## # ## !C## # # # # !C # # # #!C# # # # #^ # # # ## # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # # # # # # #!C # #!C #!C# # # # # # # ^# # # # # # # # # # ## # # ## # # !C# ^ ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # ### # ## # # !C # # #!C # # #!C # ## # !C## ## # # # # !C# # # ## # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # ## # # ### # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # #!C # # ## ## # # ## # ## # # ## ## # # #^!C # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # ## ## # # ## # # # # # !C # ## # # # #!C # ### # # # ##!C # # # # !C# #!C# ## # ## # # # !C # # ## # # ## # ## # ## ## # # ## !C# # # ## # ## # # ## #!C## # # # !C # !C# #!C # # ### # # # # # ## !C## !.### # ### # # # # ## !C # # # # # ## # #### # ## # # # # ## ## #^ # # # # # ^ # # !C# ## # # # # # # # !C## # ## # # # # # # # ## # # ##!C## ##!C# # !C# # # ## # !C### # # ^ # !C #### # # !C# ^#!C # # # !C # #!C ### ## ## #!C # ## # # # # # ## ## !C# ## # # # #!C # ## # ## ## # # # # # !C # # ^ # # ## ## ## # # # # !.!C## #!C## # ### # # # # # ## # # !C # # # # !C# # # # # # # # ## !C # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # # ## # # # ## # # ^ # # # # # # # ## !C ## # ^ # # # !C# # # # ^ # # ## #!C # # ^ -

North-West Province

© Lonely Planet Publications 509 North-West Province From safaris to slots, the pursuit of pleasure is paramount in the North-West Province. And with the top three reasons to visit less than a six-hour drive from Johannesburg, this region is more than fun. It’s convenient. Gambling is the name of the game here, although not always in the traditional sense. Place your luck in a knowledgeable ranger’s hands at Madikwe Game Reserve and bet on how many lions he’ll spot on the sunrise wildlife drive. You have to stay to play at this exclusive reserve on the edge of the Kalahari, and the lodges here will be a splurge for many. But for that once-in-a-lifetime, romantic Out of Africa–style safari experience, South Africa’s fourth-largest reserve can’t be beat. If you’d rather spot the Big Five without professional help, do a self-drive safari in Pi- lanesberg National Park. The most accessible park in the country is cheaper than Madikwe, and still has 7000 animals packed into its extinct volcano confines. Plus it’s less than three hours’ drive from Jo’burg. When you’ve had your fill betting on finding rhino, switch to cards at the opulent Sun City casino complex down the road. The final component of the province’s big attraction trifecta is the southern hemisphere’s answer to Las Vegas: a shame- lessly gaudy, unabashedly kitsch and downright delicious place to pass an afternoon. Madikwe, Pilanesberg and Sun City may be the North-West Province’s heavyweight at- tractions, but there are more here than the province’s ‘Big Three’. -

African Heritage Consultants Cc 2001/077745/23 Dr

AFRICAN HERITAGE CONSULTANTS CC 2001/077745/23 DR. UDO S KÜSEL Tel: (012) 567 6046 Fax: 086 594 9721 P.O. Box 652 Magalieskruin Cell: 082 498 0673 E-mail: [email protected] 0150 A. PHASE I CULTURAL HERITAGE RESOURCES IMPACT ASSESSMENT (a) PHASE I CULTURAL HERITAGE RESOURCES IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT OF PORTION 1 OF THE RHENOSTERSPRUIT FARM 908 JQ WITHIN THE JURISDICTION OF THE MOSES KOTANE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY WITHIN THE BOJANALA DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY IN THE NORTH WEST PROVINCE. (b) REPORT COMPILED BY Dr. Udo S. Küsel; African Heritage Consultants CC P.O. Box 653, Magalieskruin, 0150 Tel: 012 567 6046; Fax: 086 594 9721; Cell: 082 498 0673 E-mail: [email protected] (c) DEVELOPER AND CONSULTANT INFORMATION Developer: Akha Maduna Property Developers (Pty) Ltd Contact Person: Mr. N. Kubeka Address: 103 Livingstone Street, Vryburg, 8601 Tel: 053 927 3569; Cell: 072 666 2166 E-mail: [email protected] Owner: Moses Kotane Local Municipality, Private Bag X 1011 Mogwase, 0314 Tel: 014 555 1300, Fax: 014 555 6368 Consultant: Lesekha Consulting Contact Person: Lesego Senna, Address: No. 25 Caroline Close, Rowlands Estate, Mafikeng, 2745 - Tel: 018 011 0002; Cell: 083 763 7854, E-mail: [email protected] Date of report: 27 August 2018 1 B. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The site is typical Bushveld with mostly very dense vegetation. Towards the north and west a township has been developed – Mogwase and Mabele a Podi as well as the Mankwe Campus ORBIT TVET College. The site was investigated on foot and by vehicle. Especially towards the south the vegetation is very dense, this made the inspection of the site very difficult. -

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT for the PROPOSED IKAROS SUBSTATION and ASSOCIATED 400 Kv TRANSMISSION LINE INFRASTRUCTURE, NORTH WEST PROVINCE

02 April 2002 Dear I&AP, ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE PROPOSED IKAROS SUBSTATION AND ASSOCIATED 400 kV TRANSMISSION LINE INFRASTRUCTURE, NORTH WEST PROVINCE As a registered Interested and Affected Party (I&AP) for the proposed Ikaros Substation and associated 400 kV Transmission line infrastructure project in the North West Province, this newsletter aims to further facilitate your understanding of the proposed project and the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process being followed. The first phase of the EIA process (i.e. the Environmental Scoping Study) has been completed, and detailed studies are currently being undertaken within Phase 2 of the process (i.e. the EIA). The public participation process has been on-going throughout this process and will continue until the final EIA Report is submitted to the environmental authorities for decision-making. 1. REFRESHER: BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE PROPOSED PROJECT Eskom Transmission propose the construction of a new 400/132 kV substation (to be known as Ikaros Substation) on the eastern side of Rustenburg. This new substation will receive power from a 400 kV Transmission line looped in from the existing Matimba-Midas 400 kV line between Ellisras and Fochville. The primary purpose of the proposed project is to improve the reliability of the electrical supply to the towns of Brits, Marikana, Kroondal, Mooinooi and Rustenburg, as well as surrounding communities, farms, businesses, and the increasing number of platinum and chrome mines and smelters in the Rustenburg area. Electricity loads required by platinum and chrome mining and smelting in the Rustenburg area is expected to reach the combined firm capacities of the existing substations in the area (i.e. -

CHAPTER! INTRODUCTION Almost Every Activity of Man Uses Land And

CHAPTER! INTRODUCTION Almost every activity of man uses land and as human numbers and activities multiply, land has become a scarce resource. Land varies greatly in character, productivity and accessibility from place to place (Hawkies, 1978). Communication therefore becomes essential as it dictates variety of ways and alternative ways of utilizing a particular area of land (Whiteby & Willis, 1978). Communication should be understood in one of the following ways in order for one to realise his/her goals: (I) as a glue that holds everything together and a mutual process (Manning, 1987; Rogers & Kincaid, 1981). (2) Not simply the transfer ofinformation which leads to action, nor is it simply a message given, a message and receiver, rather, it begins with pre-set understanding which make effective communication possible and probable and it must start in the right way (Reilly & Di Angelo, 1990; Manning, 1987; Sanford, 1982). (3) As intercourse by words, letters or messages, interchange of thoughts or opinion by individuals, groups or public (Sereno & Mortensen, 1970; Williams, 1992). If communication is used wisely and effectively it can affect changes in the use of land use, not only applying for profitable use, but also for misuse and disuse. It is important to note that with communication, as with other types of activities, it is necessary to have criteria by which it is possible to gauge the success or failures of efforts (Fourie, 1984). It is not always possible to have exact indications such as "number of units produced" or "amount of money collected" because it is sometimes impossible to make external or objective measurements. -

Madibeng – North West

Working for integration Mookgopong Thabazimbi Modimolle Waterberg District Bela-Bela Municipality Moses Dr JS Kotane Moroka Moretele Local Municipality of Madibeng Thembisile North West Bojanala District City of Tshwane Municipality Metropolitan Municipality Rustenburg N4 City of Tshwane Kgetlengrivier Mogale City City of Ditsobotla Johannesburg Ekurhuleni Victor Ventersdorp Merafong Randfontein Khanye City Sources:Lesedi Esri, USGS, NOAA Madibeng – North West Housing Market Overview Human Settlements Mining Town Intervention 2008 – 2013 The Housing Development Agency (HDA) Block A, Riviera Office Park, 6 – 10 Riviera Road, Killarney, Johannesburg PO Box 3209, Houghton, South Africa 2041 Tel: +27 11 544 1000 Fax: +27 11 544 1006/7 Acknowledgements The Centre for Affordable Housing Finance (CAHF) in Africa, www.housingfinanceafrica.org Coordinated by Karishma Busgeeth & Johan Minnie for the HDA Disclaimer Reasonable care has been taken in the preparation of this report. The information contained herein has been derived from sources believed to be accurate and reliable. The Housing Development Agency does not assume responsibility for any error, omission or opinion contained herein, including but not limited to any decisions made based on the content of this report. © The Housing Development Agency 2015 Contents 1. Frequently Used Acronyms 1 2. Introduction 2 3. Context 5 4. Context: Mining Sector Overview 6 5. Context: Housing 7 6. Context: Market Reports 8 7. Key Findings: Housing Market Overview 9 8. Housing Performance Profile 10 9. -

KEIDEL Itinerary

GILDEA, KEIDEL AND SCHULTZ ITINERARY SOUTH AFRICA - DECEMBER 2014 DAY BY DAY DAY 1 (SUNDAY 7 DECEMBER) Pick up your rental car and head towards Lesedi Cultural Village. Your accommodation on the 6th had not been confirmed yet, but more than likely the fire and ice hotel in Melrose Arch, in which case the following directions are suitable. From Johannesburg take the M1 north towards Pretoria, (the highway right next to Melrose Arch) and then turn west onto the N1 at the Woodmead interchange, following signs to Bloemfontein (Roughly 10km after you get onto the highway). At the Malabongwe drive off-ramp (roughly another 10 km), turn off and then turn right onto Malabongwe drive (R512), proceed for 40 kms along the R512, Lesedi is clearly marked on the left-hand side of the rd. The Lesedi Staff will meet you on arrival. Start your journey at the Ndebele village with an introduction to the cultural experience preceded by a multi-media presentation on the history and origins of South Africa’s rainbow nation. Then, enjoy a guided tour of the other four ethnic homesteads – Zulu, Basotho, Xhosa and Pedi. As the sun sets over the African bush, visit the Boma for a very interactive affair of traditional singing and dancing, which depict stories dating back to the days of their ancestors. Dine in the Nyama Choma Restaurant, featuring ethnic dishes, a fusion of Pan African cuisine all complemented by warm, traditional service. Lesedi African Lodge and Cultural Village Kalkheuwel, Broederstroom R512, Lanseria, 1748 [t] 087 940 9933 [m] 071 507 1447 DAY 2 – 4 (MONDAY 8 DECEMBER – WEDNESDAY 10 DECEMBER) After a good night’s sleep awaken to the sounds of traditional maskande guitar or squash-box, and enjoy a full English breakfast, which is served in the restaurant. -

GCRO 2009 Quality of Life Survey Field

N 1 1 Modimolle Makhuduthamaga Thabazimbi Mookgopong GCRO 2009 QuaL iilmityp o opfo Life Survey Field Map Thabazimbi Greater Tubatse Greater Marble Hall / 1 Bela-Bela N Greater Tubatse Moses Kotane Siyabuswa 294 Dr JS Moroka Assen 104 Moretele Elias Motsoaledi Ramotshere Moiloa 18 North Eastern Region Motshikiri 249 Makgabetlwane 235 Beestekraal 112 Temba 306 Babelegi 106 Tswaing 313 Hammanskraal 180 Local Municipality of Madibeng Kwamhlanga 215 Thembisile Maboloko 231 Ga-Mokone 170 Winterveld 333 Moloto 247 Letlhabile 224 Klippan 206 Sybrandskraal 305 Boshoek 121 Rooiwal 283 13 Nokeng tsa Taemane Mabopane 232 Ga-Luka 169 Rashoop 277 Emakhazeni Hebron 184 Bethanie 116 Lerulaneng 223 0 Phokeng 265 8 Selonsrivier 290 Elandsrand 156 R Lammerkop 217 N 14 North Western Region De Wildt 142 Bon Accord 119 4 Akasia 100 Bynespoort 127 Wonderhoek 336 Sonop 297 Cullinan 137 Photsaneng 266 Onderstepoort 258 Marikana 239 Sonderwater 296 Ekangala 154 Mafikeng Rustenburg Pretoria North 270 Mamelodi 236 Jacksonstuin 193 Hartbeespoort 183 Pretoria 269 Kroondal 212 Rayton 279 Kromdraai 211 Kgetlengrivier Mooinooi 248 Mhluzi 241 Kosmos 209 N4 1 Tshwane Middelburg (MP) 242 Garsfontein 172 Pelindaba 263 Bronkhorstspruit 126 4 Skeerpoort 295 Erasmia 163 Valhalla 315 N Centurion 130 Die Moot 146 Tierpoort 309 Balmoral 107 Steve Tshwete Doornrandjies 148 Irene 192 KwaGuqa 214 Witbank 334 Hekpoort 186 14 N 12 Kungwini Clewer 133 N o rr tt h W e s tt Maanhaarrand 230 Pinedene 267 4 West Rand Randjiesfontein 275 Welbekend 328 Elberta 158 1 Boons 120 Midrand 243 -

North West No Fee Schools 2020

NORTH WEST NO FEE SCHOOLS 2020 NATIONAL EMIS NAME OF SCHOOL SCHOOL PHASE ADDRESS OF SCHOOL EDUCATION DISTRICT QUINTILE LEARNER NUMBER 2020 NUMBERS 2020 600100023 AMALIA PUBLIC PRIMARY PRIMARY P.O. BOX 7 AMALIA 2786 DR RUTH S MOMPATI 1 1363 600100033 ATAMELANG PRIMARY PRIMARY P.O. BOX 282 PAMPIERSTAD 8566 DR RUTH S MOMPATI 1 251 600100036 AVONDSTER PRIMARY PRIMARY P.O. BOX 335 SCHWEIZER-RENEKE 2780 DR RUTH S MOMPATI 1 171 600100040 BABUSENG PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P.O. BOX 100 LERATO 2880 NGAKA MODIRI MOLEMA 1 432 600100045 BADUMEDI SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY P. O. BOX 69 RADIUM 0483 BOJANALA 1 591 600100049 BAGAMAIDI PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P.O BOX 297 HARTSWATER 8570 DR RUTH S MOMPATI 1 247 600103614 BAHENTSWE PRIMARY P.O BOX 545 DELAREYVILLE 2770 NGAKA MODIRI MOLEMA 1 119 600100053 BAISITSE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P.O. BOX 5006 TAUNG 8584 DR RUTH S MOMPATI 1 535 600100056 BAITSHOKI HIGH SCHOOL SECONDARY PRIVATE BAG X 21 ITSOSENG 2744 NGAKA MODIRI MOLEMA 1 774 600100061 BAKGOFA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P O BOX 1194 SUN CITY 0316 BOJANALA 1 680 600100067 BALESENG PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P. O. BOX 6 LEBOTLOANE 0411 BOJANALA 1 232 600100069 BANABAKAE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P.O. BOX 192 LERATO 2880 NGAKA MODIRI MOLEMA 1 740 600100071 BANCHO PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY PRIVATE BAG X10003 MOROKWENG 8614 DR RUTH S MOMPATI 1 60 600100073 BANOGENG MIDDLE SCHOOL SECONDARY PRIVATE BAG X 28 ITSOSENG 2744 NGAKA MODIRI MOLEMA 1 84 600100075 BAPHALANE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P. O. BOX 108 RAMOKOKASTAD 0195 BOJANALA 1 459 600100281 BARETSE PRIMARY PRIMARY P.O. -

Organisational Development, Head Office

O R G A N I S A T I O N A L D E V E L O P M E N T , H E A D O F F I C E Coordinate System: Sphere Cylindrical Equal Area Projection: Cylindrical Equal Area Datum: Sphere North West Clusters False Easting: 0.0000 False Northing: 0.0000 Central Meridian: 0.0000 Standard Parallel 1: 0.0000 Units: Meter µ VAALWATER LEPHALALE LEPHALALE RANKIN'S PASS MODIIMOLLE DWAALBOOM THABAZIMBI MODIMOLLE BELA--BELA ROOIBERG BELA-BELA NORTHAM NIETVERDIEND MOTSWEDI BEDWANG CYFERSKUIL MOGWASE MADIKWE SUN CITY ASSEN KWAMHLANGA RUSTENBURG JERICHO MAKAPANSTAD ZEERUST PIENAARSRIVIER RIETGATTEMBA BRITS DUBE LETHABONG BRITS LOATEHAMMANSKRAAL LEHURUTSHE LETHLABILE GROOT MARICO KLIPGAT MOKOPONG ZEERUST PHOKENG TSHWANE NORTH MOTHUTLUNGHEBRONSOSHANGUVE CULLINAN BETHANIE SWARTRUGGENS BRITS GA-RANKUWAPRETORIA NORTH BOITEKONG BRAY TLHABANE MMAKAU TSHWANE EAST MARIKANA AKASIA SINOVILLE OTTOSHOOP HERCULES MOOINOOI ATTERIDGEVILLE SILVERTON MAHIKENG RUSTENBURG HARTBEESPOORTDAM MAKGOBISTAD TSHWANE WEST MMABATHO LYTTELTON TSHIDILAMOLOMO KOSTER ERASMIA HEKPOORT VORSTERSHOOP BOSHOEK DIEPSLOOTMIDRAND WELBEKEND LICHTENBURG MULDERSDRIFT LOMANYANENG BOONSMAGALIESBURGKRUGERSDORPJOBURG NORTH TARLTON ITSOSENG JOBURG WEST KEMPTON PARK SETLAGOLE HONEYDEWSANDTON KAGISO BENONI MOROKWENG RANDFONTEIN PIET PLESSIS MAHIKENG EKHURULENII CENTRAL MAHIKENG WEST RAND ALBERTON WEST RAND BRAKPAN VRYBURG MOOIFONTEIN KLERKSKRAAL CARLETONVILLE MONDEOR VENTERSDORP KHUTSONG SOWETO WEST DAWN PARK HEUNINGVLEI BIESIESVLEI COLIGNY MADIBOGO ATAMELANG WESTONARIA EKHURULENII WEST WEDELA ENNERDALEDE DEUR ORANGE -

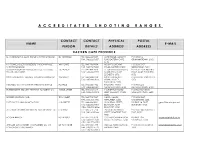

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

North West Brits Main Seat of Madibeng Magisterial District Main Seat / Sub District Within the Magisterial District

# # !C # # ### ^ !.C!# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # !C # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # !C # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # #!C# # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # #!C # # !C # # #^ # # # # # # ## # # # # #!C # # # # #!C # # # # # # !C# ## # # # # # !C # # #!C## # # # ^ # # # # # # ## # # # # # !C # # # # ## # # # # # # # # ##!C # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # ## # # # !C # # # # !C # # # ## ## ## ## # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C # # !C# # ^ # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## ## # # !C ##^ # !C #!C## # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # # # !C# ^ ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # # # # !C # #!C # # # #!C # # # !C## ## # # # # !C # # ## # # # # # ## # # # # # ## # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # #!C ## ## # # # # # # ## # # # ^!C # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # ## #!C # # # # # ## #!C # !C # # # # !C## #!C # # # # # # # # ## # ## # !C# # # ## # # ## # ## # # # # # # # ## # # # # ## !C# # # # # # # # !C# # #### !C## # # !C # # ##!C !C # #!.# # # # # # ## ## # #!C# # # # # # # # ## # # # # ## # # # # # # # # ## ## ##^ # # # # # !C ## # # ## # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # !C# ## ## ## # # # ### # # # #!C## !C# # !C# # # ## # !C### # # ^ # !C ## # # # !C# ^##!C # # !C ## # # # # !C # # # #!C# # ## # # # # ## ## # # # # # # !C # # # # # #!C # # # ## ## # # # # # !C # # ^ # ## # ## # # # # !.!C ## # # ## # # # !C # # # !C# # ### # # # # # # # # # ## # !C ## # # # # # ## !C # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # #