EISA Election Update Eight SA Elections 2014: the Media And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premier Zille Needs to Walk Her Talk on Street-Lighting Crisis in Khayelitsha

CAPE TIMES WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 23, 2013 INSIGHT 9 Failure of the food market means many in our city go hungry Rocks and Jane Battersby-Lennard increasingly urban challenge. Security Urban Network, which context of high-energy costs and Afsun’s (the writers of this arti- strong social capital in the poor bullets and Jonathan Crush With a population approaching aims to address the challenges asso- long commutes to work makes these cle) findings reinforce the fact that, areas of the city, it also points to a 4 million, Cape Town has a particu- ciated with rising poverty and food foods less viable. in the urban setting, there are mul- failure of the market and of formal WITH food price increases outstrip- larly rapid annual growth rate of insecurity in Africa’s cities, found The proportion of households tiple causes of food insecurity. social safety nets. shatter ping South Africa’s official inflation 3.2 percent. Migration accounts for very high food insecurity in the consuming fish was also lower than There is also a range of stake- Engagement among NGOs, civil rate, and hunger and malnutrition about 41 percent of this growth and three Cape Town areas that it expected (only 16 percent) despite holders playing a role in the urban society and the state should be in Cape Town at worrying levels, the natural increase the rest. researched. the fisheries history of Ocean View. food system. As a result, the solution encouraged to put in place safety peaceful city urgently needs to develop a Addressing food insecurity in In both Philippi and Khayelitsha, Very little fresh fish is consumed; to food insecurity cannot simply be nets that neither create dependency food security strategy that goes cities like Cape Town is essential, less than 10 percent of households most comes in the form of canned linked to local and national policy nor destroy existing social safety beyond a focus on production. -

Government System Systems

GovernmentGovernment system systems YEARBOOK 2011/12 Government system 11 The Government of South Africa is committed to The Constitution building a free, non-racial, non-sexist, democratic, South Africa’s Constitution is one of the most united and successful South Africa. progressive in the world and enjoys high acclaim The outcomes approach, which started in 2010, internationally. Human rights are given clear is embedded in and a direct result of the electoral prominence in the Constitution. mandate. Five priority areas have been identified: The Constitution of the Republic of South decent work and sustainable livelihoods, educa- Africa, 1996 was approved by the Constitutional tion, health, rural development, food security and Court on 4 December 1996 and took effect on land reform and the fight against crime and cor- 4 February 1997. ruption. These have been translated into the fol- The Constitution is the supreme law of the land. lowing 12 outcomes to create a better life for all: No other law or government action can supersede • better quality basic education the provisions of the Constitution. • a long and healthy life for all South Af- ricans The Preamble • all South Africans should be safe and feel safe The Preamble states that the Constitution aims • decent employment through inclusive growth to: • a skilled and capable workforce to support an • heal the divisions of the past and establish a inclusive growth path society based on democratic values, social Government systems• an efficient, competitive and responsive eco- justice -

Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport Annual Report 2011/2012

Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport Annual Report 2011/2012 Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport – Annual Report 2011/2012 Dr IH Meyer Western Cape Minister of Cultural Affairs, Sport and Recreation I have the honour of submitting the Annual Report of the Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport for the period 1 April 2011 to 31 March 2012. _______________ BRENT WALTERS 31 August 2012 Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport – Annual Report 2011/2012 Contents PART 1: GENERAL INFORMATION .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Vision, mission and values ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Organisational structure ................................................................................................................................ 2 1.3 Legislative mandate ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Entities reporting to the Minister ................................................................................................................... 8 1.5 Minister’s statement ....................................................................................................................................... 9 1.6 Accounting Officer’s overview ................................................................................................................. -

Cape Librarian July/August 2014 | Volume 58 | No

Cape Librarian July/August 2014 | Volume 58 | No. 4 Kaapse Bibliotekaris contents | inhoud FEATURES | ARTIKELS WE WILL REMEMBER 12 Dr Gustav Hendrich COLUMNS | RUBRIEKE BOOK WORLD | BOEKWÊRELD Literary Awards | Literêre Toekennings 17 The 2013/2014 update Compiled by / Saamgestel deur Sabrina Gosling, Theresa Sass and / en Stanley Jonck Sarie Marais: ’n dame met styl en ervaring 26 Dr Francois Verster Daar’s lewe by die Franschhoekse Literêre Fees 29 Dr Francois Verster Book Reviews | Boekresensies 31 Compiled by Book Selectors / Saamgestel deur Boekkeurders Accessions | Aanwinste 37 Compiled by / Saamgestel deur Johanna de Beer Library Route | Die Biblioteekroete Introducing Blaauwberg Region 39 Compiled by Grizéll Azar-Luxton Workroom | Werkkamer A trio of topics 45 Compiled by Marilyn McIntosh Spotlight on SN | Kollig op SN World War I anniversary 48 Dalena le Roux NEWS | NUUS between the lines / tussen die lyne 2 mense / people 3 biblioteke / libraries 4 skrywers en boeke / books and authors 6 allerlei / miscellany 7 skrywersdinge / about authors 10 40 years . 11 coVer | Voorblad This year’s cover is a representation of book characters. This month Batman swoops down onto the cover. Vanjaar se voorblad is ’n voorstelling van boekkarakters. Hierdie maand is dit Batman se beurt om op die voorblad te land. editorial sold. Today, 65 years later, Sarie is a household name - a monthly magazine loved by thousands of readers. Follow her development on page 26 as told by Francois Verster. ugustusmaand is vir baie lande in die wêreld die honderdjarige herdenking sedert die eerste wêreldoorlog A– en die nagedagtenis aan die skokkende gebeure wat tot die vernietiging van wêreldryke sou lei. -

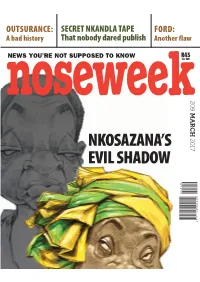

Nkosazana's Evil Shadow

OUTSURANCE: SECRET NKANDLA TAPE FORD: A bad history That nobody dared publish Another flaw R45 NEWS YOU’RE NOT SUPPOSED TO KNOW (inc VAT) noseweek209 MARCH MARCH NKOSAZANA’S 2017 EVIL SHADOW 00209 104042 771025 9 GB NoseWeek MCC Ad_02.indd 1 2016/12/12 2:03 PM Your favourite magazine is now ISSUE 209 • MARCH 2017 available on your iPad and PC Stent Page 10 FEATURES 9 Notes & Updates 4 Letters Appeal against Tongaat-Hulett pensions ruling 8 Editorial n Mpisanes: the paper chase n Second guessing America First 38 Smalls 12 Nkosazana’s evil shadow AVAILABLE Bathabile Dlamini’s history of dishonesty and disasterous mismanagement of SA’s social grants ON YOUR COLUMNS programme likely to sink Nkosazana’s chances of TABLET becoming president 33 Africa 13 A shocking taped phone conversation 34 Books A leaked recording draws the spotlight onto the financial and political ambitions of Zuma’s women Download your 35 Down & digital edition today Out 16 Road swindle: tarred and feathered Contractor overcharged hugely 36 Letter from both single issues and Umjindi 20 Petrol consumption figures fuel Ford’s fire subscriptions available 37 Last Word Doughty widow challenges advertising claims PLUS never miss a copy – 22 Sweet talk with back issues available to A brand of purportedly diabetic-friendly agave download and store nectar is putting South African lives at risk 26 Leuens Botha and the weird weir DOWNLOAD YOUR DIGITAL The many faces and many schemes of a DA politician EDITION AT 28 Bad policy www.noseweek.co.za How to fight insurance claim blackmail or % 021 686 0570 30 On wings of song Cape Town’s Youth Choir plans to conquer New York NOSEWEEK March 2017 3 Letters Barry Sergeant an instant friend the scales of the legal minions slith- calls and trips to various places ering around Facebook instead of they have told her it’s her own fault I’M SO SAD ABOUT BARRY SERGEANT’S respecting your right to a healthy and said someone has been buying death. -

MEC Mac Jack Handing Over of Edukite Hard and Software

1 | P a g e Keynote Address- MEC Mac Jack Handing over of Edukite Hard-and Software Northern Cape High School Friday, 2 August 2019 Senior Management of the Department of Education; Educators present; Distinguished guest; Ladies and Gentleman; Members of the media It gives me great pleasure to officiate this auspicious occasion which will equip educators with 21st century technology as we prepare learners for the 4th industrial revolution. The premise of our input this afternoon is a question that revolves around the 4th industrial revolution. “What do steam, science and digital technology have in common?” These are the first 3 industrial revolutions that transformed our modern society. 1 | P a g e 2 | P a g e With each of these advancements the steam engine, the age of science, mass production and the rise of digital technology fundamentally changed the world around us. And right now, it’s happening again, for a fourth time. Each of these first 3 industrial revolutions represented profound change. We are talking major societal transformation. So where are we now? Well at this moment, many of the technologies people dreamed off in the 1950’s and 1960’s have become a reality. Maybe we don’t have flying cars yet, but we have robots, plus there’s genetic sequencing and editing, artificial intelligence, miniaturized sensors and 3D printing too mention a few. And when you put all these technologies together, well, let just say the innovations are unexpected and surprising. This is the beginning of the next great industrial revolution, the 4th industrial revolution. -

MEC Mac Jack State of the Province (SOPA) Debate

SOPA Debate MEC Mac Jack Northern Cape Provincial Legislature Tuesday, 9 July 2019 _____________________________________________ Speaker and Deputy Speaker of the Provincial Legislature; Premier Dr. Zamani Saul; Members of the Executive Council; Members from the Northern Cape Provincial Legislature; Traditional Leaders; Director General, Heads of Department and Leaders of Public Service; Political parties present; Members of the media; As we enter a new era of hope to further improve the basic living conditions and lives of all our people, we draw inspiration, courage and determination from a rastafarian of note, Jimmy Cliff, who once sang a song, “Remake the World”, and I quote: 1 | P a g e “Too many people are suffering, Too many people are sad, Too little people, got everything, While too many people got nothing”. As I thought about that song, we need to mobilise the Northern Cape community behind the vision of a Modern, Growing and Successful Northern Cape Province. Over the past 25 years of democracy, concerted efforts were made to address the triple challenges of poverty, unemployment and inequality in the Province. Today, we look back full of pride because of what the ANC, its allies and the people of this country have achieved. Although much has been achieved, we could have moved faster and the quality of services could have been much better. Many of our people are still longing for their own home, a decent work opportunity, good health services, quality public education system, safer communities and many more. 2 | P a g e The Freedom Charter remains our inspiration and our strategic guide to realising a better life and a South Africa that truly belongs to all who live in it. -

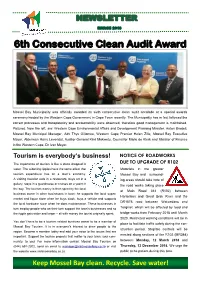

6Th Consecutive Clean Audit Award

MARCH 2018 6th Consecutive Clean Audit Award Mossel Bay Municipality was officially awarded its sixth consecutive clean audit accolade at a special awards ceremony hosted by the Western Cape Government in Cape Town recently. The Municipality has in fact followed the correct processes and transparency and accountability were observed, therefore good management is maintained. Pictured, from the left, are: Western Cape Environmental Affairs and Development Planning Minister, Anton Bredell, Mossel Bay Municipal Manager, Adv Thys Giliomee, Western Cape Premier Helen Zille, Mossel Bay Executive Mayor, Alderman Harry Levendal, Auditor-General Kimi Makwetu, Councillor Marie de Klerk and Minister of Finance in the Western Cape, Dr Ivan Meyer. Tourism is everybody’s business! NOTICE OF ROADWORKS The importance of tourism is like a stone dropped in DUE TO UPGRADE OF R102 water. The widening ripples have the same effect that Motorists in the greater tourism expenditure has on a town’s economy. Mossel Bay and surround- A visiting traveller eats in a restaurant, buys art in a ing areas should take note of gallery, stays in a guesthouse or cruises on a yacht in the road works taking place the bay. The tourism money is then spent by the local at Main Road 344 (R102) between business owner in other businesses in town: he supports the local super- Hartenbos and Great Brak River and the market and liquor store when he buys stock, buys a vehicle and supports DR1578 road between Wolwedans and the local hardware store when he does maintenance. These businesses in turn employ people who on their turn support the town’s businesses and so Tergniet, which will be affected by road and the ripple gets wider and larger – all with money the tourist originally spent. -

African National Congress NATIONAL to NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob

African National Congress NATIONAL TO NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob Gedleyihlekisa 2. MOTLANTHE Kgalema Petrus 3. MBETE Baleka 4. MANUEL Trevor Andrew 5. MANDELA Nomzamo Winfred 6. DLAMINI-ZUMA Nkosazana 7. RADEBE Jeffery Thamsanqa 8. SISULU Lindiwe Noceba 9. NZIMANDE Bonginkosi Emmanuel 10. PANDOR Grace Naledi Mandisa 11. MBALULA Fikile April 12. NQAKULA Nosiviwe Noluthando 13. SKWEYIYA Zola Sidney Themba 14. ROUTLEDGE Nozizwe Charlotte 15. MTHETHWA Nkosinathi 16. DLAMINI Bathabile Olive 17. JORDAN Zweledinga Pallo 18. MOTSHEKGA Matsie Angelina 19. GIGABA Knowledge Malusi Nkanyezi 20. HOGAN Barbara Anne 21. SHICEKA Sicelo 22. MFEKETO Nomaindiya Cathleen 23. MAKHENKESI Makhenkesi Arnold 24. TSHABALALA- MSIMANG Mantombazana Edmie 25. RAMATHLODI Ngoako Abel 26. MABUDAFHASI Thizwilondi Rejoyce 27. GODOGWANA Enoch 28. HENDRICKS Lindiwe 29. CHARLES Nqakula 30. SHABANGU Susan 31. SEXWALE Tokyo Mosima Gabriel 32. XINGWANA Lulama Marytheresa 33. NYANDA Siphiwe 34. SONJICA Buyelwa Patience 35. NDEBELE Joel Sibusiso 36. YENGENI Lumka Elizabeth 37. CRONIN Jeremy Patrick 38. NKOANA- MASHABANE Maite Emily 39. SISULU Max Vuyisile 40. VAN DER MERWE Susan Comber 41. HOLOMISA Sango Patekile 42. PETERS Elizabeth Dipuo 43. MOTSHEKGA Mathole Serofo 44. ZULU Lindiwe Daphne 45. CHABANE Ohm Collins 46. SIBIYA Noluthando Agatha 47. HANEKOM Derek Andre` 48. BOGOPANE-ZULU Hendrietta Ipeleng 49. MPAHLWA Mandisi Bongani Mabuto 50. TOBIAS Thandi Vivian 51. MOTSOALEDI Pakishe Aaron 52. MOLEWA Bomo Edana Edith 53. PHAAHLA Matume Joseph 54. PULE Dina Deliwe 55. MDLADLANA Membathisi Mphumzi Shepherd 56. DLULANE Beauty Nomvuzo 57. MANAMELA Kgwaridi Buti 58. MOLOI-MOROPA Joyce Clementine 59. EBRAHIM Ebrahim Ismail 60. MAHLANGU-NKABINDE Gwendoline Lindiwe 61. NJIKELANA Sisa James 62. HAJAIJ Fatima 63. -

MEC Matsemela Congratulates Olympiad Participants DA No Surprised by Irresponsible CFO’S Supra’S Threat - P3 Irk MEC Rosho - P5

Read us and advertise online - www.mafikengmail.co.za - like Learners of the winning schools proudly display their trophies and medals won during the Maths Olympiad compe� � on. MEC Matsemela congratulates Olympiad participants DA no Surprised by Irresponsible CFO’s Supra’s threat - p3 Irk MEC Rosho - p5 FREE RUGBY FEATURE INSIDE Established 1889 13 Martin Street; Galleria Arcade; Shop no 1 & 2 E-mail: mailbag@mafi kengmail.co.za GPS Co-ordinates: 25” 51’ 49,42 S • 25” 35’ 40,52 E 27 SEPTEMBER 2019 Tel: 018 381 1330/ 381 2884 Fax: 018 381 0425 R4-00 VAT INCL PAGE 2 MAHIKENG MAIL 27 SEPTEMBER 2019 Seletedi Sekgororoane Family reunion The Good news Column Psalm8:1 Psalm of David. O Lord, our Lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth! You have set your glory above the heavens .Out of the mouth of babies and infants, you have established strength because of your foes, to still the enemy and avenger. When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars which you have set in place. What is the man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him. You have made him a little lower than the heavenly beings and crowned him with glory and honour. You have given him dominion over the works of your hands; you have put all things under his feet. All sheep and oxen, and also the beasts of the field, the birds of the heavens and the fish of the sea, whatever passes along the paths of As a norm for every year, the Seletedi family gathered, reunited and strengthened their family ties when this year they the seas .O Lord, our Lord, how majestic is celebrated their reunion in style in Majemantsho Village near Mafikeng recently. -

NEWSLETTER of the NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCIAL TREASURY ISSUE 25 Beginning of Story

Heading Sub-Heading NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCIAL TREASURY By line if there is no sub-heading Beginning of story if there is no sub heading By line if there is a sub-heading THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCIAL TREASURY ISSUE 25 Beginning of story Page 1: Treasury welcomes MEC MacCollen Jack Page 2: Face to Face with HRD Page 3: Northern Cape tightens the budget belt Page 4: The key to a productive workplace Page 5: GEPF allay pension fears Page 6: Management Strategic Session Page 7: One on One with Lizel Fillis Page 8: * Power Mondays * NCPT at play * Benefits of sleep Page 9: Events Photo Gallery Backpage: * Meet the new ministerial team * People on the move The new MEC for Finance, Economic Development and Tourism, Mr MacCollen Jack Heading Editor’s Note Dear reader, Sub-Heading By line if there is no sub-heading It is an honour to serve as the new editor of this newsletter following the departure of my Beginning of story if there is no sub heading By line if there is a sub-heading predecessor, Mr Mojalefa Mphapang, who I believe did an outstanding work by ensuring Beginning of story that the newsletter serves as a mirror through which we are able to look back at the work we are doing for the province. I intend to ensure that this publication will educate you about the economy, highlight the accomplishments of dedicated officials, keep you informed about new developments like promotions, appointments, including other matters that affect your health as well as managing finances. -

Eastern Cape Government Accountability Report

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA THE EASTERN CAPE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT MIDTERM ACCOUNTABILITY REPORT 2014-2016 GOVERNMENT MIDTERM ACCOUNTABILITY REPORT 2014-2016 1 CONTENTS 6 1 Foreword – Premier Phumulo Masualle THE EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE AT A GLANCE Providing Quality Education: Government’s 6 Apex Priority • Home to 7 million people. • Population has increased by 14% between 1996 and 2016 An improved health profile of the province 9 • National population has increased by 37% Integrated human settlements and building • 1 914 036 people migrated out of the province while only 320 619 11 cohesive communities people migrated into the province, leading to a net outward migra- tion of -1 593 417 people compared to a net outward migration -1 592 798 recorded in census 2011. 13 Strategic social infrastructure interventions • The number of households increased by 36% from 1.3 million in 1996 to 1.8 million in 2016. Stimulating rural development, land reform 15 and food security • Whilst the number of households is increasing, the household size is decreasing. The increase in the number of households has impli- Intensify the fight against crime and cations for delivery of basic services, including human settlements 18 corruption development. Transform the economy to create jobs and • The poverty headcount of the province has decreased from 14.4% in 21 sustain livelihoods 2011 to 12. 7% in 2016, however the province maintains the highest poverty headcount amongst all provinces. Strengthening the developmental state and • Decreases in the poverty headcount were observed across all 24 good governance district municipalities, except for Chris Hani, where it increased from Provincial and municipal audit outcomes 15.