My Phd Research Is a Comparative Exploration of Chinese Fiction in the Late Imperial Period (DATES) Focusing in Particular On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qing Shi (The History of Love) in Late Ming Book Culture

Asiatische Studien Études Asiatiques LXVI · 4 · 2012 Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft Revue de la Société Suisse – Asie Aspects of Emotion in Late Imperial China Peter Lang Bern · Berlin · Bruxelles · Frankfurt am Main · New York · Oxford · Wien ISSN 0004-4717 © Peter Lang AG, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften, Bern 2012 Hochfeldstrasse 32, CH-3012 Bern [email protected], www.peterlang.com, www.peterlang.net Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschliesslich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung ausserhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. Printed in Hungary INHALTSVERZEICHNIS – TABLE DES MATIÈRES CONTENTS Nachruf – Nécrologie – Obituary JORRIT BRITSCHGI..............................................................................................................................877 Helmut Brinker (1939–2012) Thematic Section: Aspects of Emotion in Late Imperial China ANGELIKA C. MESSNER (ED.) ......................................................................................................893 Aspects of Emotion in Late Imperial China. Editor’s introduction to the thematic section BARBARA BISETTO ............................................................................................................................915 The Composition of Qing shi (The History of Love) -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

The University of Chicago Practices of Scriptural Economy: Compiling and Copying a Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Anthology A

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRACTICES OF SCRIPTURAL ECONOMY: COMPILING AND COPYING A SEVENTH-CENTURY CHINESE BUDDHIST ANTHOLOGY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVINITY SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ALEXANDER ONG HSU CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2018 © Copyright by Alexander Ong Hsu, 2018. All rights reserved. Dissertation Abstract: Practices of Scriptural Economy: Compiling and Copying a Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Anthology By Alexander Ong Hsu This dissertation reads a seventh-century Chinese Buddhist anthology to examine how medieval Chinese Buddhists practiced reducing and reorganizing their voluminous scriptural tra- dition into more useful formats. The anthology, A Grove of Pearls from the Garden of Dharma (Fayuan zhulin ), was compiled by a scholar-monk named Daoshi (?–683) from hundreds of Buddhist scriptures and other religious writings, listing thousands of quotations un- der a system of one-hundred category-chapters. This dissertation shows how A Grove of Pearls was designed by and for scriptural economy: it facilitated and was facilitated by traditions of categorizing, excerpting, and collecting units of scripture. Anthologies like A Grove of Pearls selectively copied the forms and contents of earlier Buddhist anthologies, catalogs, and other compilations; and, in turn, later Buddhists would selectively copy from it in order to spread the Buddhist dharma. I read anthologies not merely to describe their contents but to show what their compilers and copyists thought they were doing when they made and used them. A Grove of Pearls from the Garden of Dharma has often been read as an example of a Buddhist leishu , or “Chinese encyclopedia.” But the work’s precursors from the sixth cen- tury do not all fit neatly into this genre because they do not all use lei or categories consist- ently, nor do they all have encyclopedic breadth like A Grove of Pearls. -

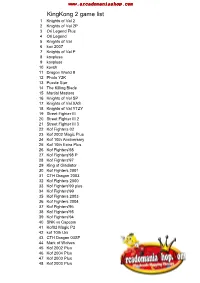

Kingkong 2 Game List

www.arcadomaniashop.com KingKong 2 game list 1 Knights of Val 2 2 Knights of Val 2P 3 Ori Legend Plus 4 Ori Legend 5 Knights of Val 6 kov 2007 7 Knights of Val P 8 kovplusa 9 kovpluss 10 kovsh 11 Dragon World II 12 Photo Y2K 13 Puzzle Star 14 The Killing Blade 15 Martial Masters 16 Knights of Val SP 17 Knights of Val XAS 18 Knights of Val YTZY 19 Street Fighter III 20 Street Fighter III 2 21 Street Fighter III 3 22 Kof Fighters 02 23 Kof 2002 Magic Plus 24 Kof 10th Anniversary 25 Kof 10th Extra Plus 26 Kof Fighters'98 27 Kof Fighters'98 P 28 Kof Fighters'97 29 King of Gladiator 30 Kof Fighters 2001 31 CTH Dragon 2003 32 Kof Fighters 2000 33 Kof Fighters'99 plus 34 Kof Fighters'99 35 Kof Fighters 2003 36 Kof Fighters 2004 37 Kof Fighters'96 38 Kof Fighters'95 39 Kof Fighters'94 40 SNK vs Capcom 41 Kof02 Magic P2 42 kof 10th Uni 43 CTH Dragon 03SP 44 Mark of Wolves 45 Kof 2002 Plus 46 Kof 2004 Plus 47 Kof 2003 Plus 48 Kof 2000 Plus www.arcadomaniashop.com 49 Kof 2001 Plus 50 Kof 2003 Hero 51 DoubleDragon Plus 52 Kof 95 Plus 53 Kof 96 Plus 54 Kof 97 Plus 55 Metal Slug 56 Metal Slug 2 57 Metal Slug 3 58 Metal Slug 4 59 Metal Slug 5 60 Metal Slug 6 61 Metal Slug x 62 Metal Slug Plus 63 Metal Slug 2 Plus 64 Metal Slug 3 Plus 65 Metal Slug 4 Plus 66 Metal Slug 5 Plus 67 Metal Slug 6 Plus 68 1941 69 Cadillacs & Dino 70 Cadillacs & Dino 2 71 Captain Commando 72 Knights of Round 73 Knights of Round SH 74 Mega Twins 75 The king of Dragons 76 punisher 77 San Jian Sheng 78 Warriors of Fate 79 Three Wonders 80 Sangokushi II 81 Dynasty Wars 82 Magic -

International Reinterpretations

International Reinterpretations 1 Remakes know no borders… 2 … naturally, this applies to anime and manga as well. 3 Shogun Warriors 4 Stock-footage series 5 Non-US stock-footage shows Super Riders with the Devil Hanuman and the 5 Riders 6 OEL manga 7 OEL manga 8 OEL manga 9 Holy cow, more OEL manga! 10 Crossovers 11 Ghost Rider? 12 The Lion King? 13 Godzilla 14 Guyver 15 Crying Freeman 16 Fist of the North Star 17 G-Saviour 18 Blood: the Last Vampire 19 Speed Racer 20 Imagi Studios 21 Ultraman 6 Brothers vs. the Monster Army (Thailand) The Adventure Begins (USA) Towards the Future (Australia) The Ultimate Hero (USA) Tiga manhwa 22 Dragonball 23 Wicked City 24 City Hunter 25 Initial D 26 Riki-Oh 27 Asian TV Dramas Honey and Clover Peach Girl (Taiwan) Prince of Tennis (Taiwan) (China) 28 Boys Over Flowers Marmalade Boy (Taiwan) (South Korea) Oldboy 29 Taekwon V 30 Super Batman and Mazinger V 31 Space Gundam? Astro Plan? 32 Journey to the West (Saiyuki) Alakazam the Great Gensomaden Saiyuki Monkey Typhoon Patalliro Saiyuki Starzinger Dragonball 33 More “Goku”s 34 The Water Margin (Suikoden) Giant Robo Outlaw Star Suikoden Demon Century Akaboshi 35 Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sangokushi) Mitsuteru Yokoyama’s Sangokushi Kotetsu Sangokushi BB Senshi Sangokuden Koihime Musou Ikkitousen 36 World Masterpiece Theater (23 seasons since 1969) Moomin Heidi A Dog of Flanders 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother Anne of Green Gables Adventures of Tom Sawyer Swiss Family Robinson Little Women Little Lord Fauntleroy Peter -

Ever Faithful

Ever Faithful Ever Faithful Race, Loyalty, and the Ends of Empire in Spanish Cuba David Sartorius Duke University Press • Durham and London • 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Tyeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sartorius, David A. Ever faithful : race, loyalty, and the ends of empire in Spanish Cuba / David Sartorius. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 8223- 5579- 3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978- 0- 8223- 5593- 9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Blacks— Race identity— Cuba—History—19th century. 2. Cuba— Race relations— History—19th century. 3. Spain— Colonies—America— Administration—History—19th century. I. Title. F1789.N3S27 2013 305.80097291—dc23 2013025534 contents Preface • vii A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s • xv Introduction A Faithful Account of Colonial Racial Politics • 1 one Belonging to an Empire • 21 Race and Rights two Suspicious Affi nities • 52 Loyal Subjectivity and the Paternalist Public three Th e Will to Freedom • 94 Spanish Allegiances in the Ten Years’ War four Publicizing Loyalty • 128 Race and the Post- Zanjón Public Sphere five “Long Live Spain! Death to Autonomy!” • 158 Liberalism and Slave Emancipation six Th e Price of Integrity • 187 Limited Loyalties in Revolution Conclusion Subject Citizens and the Tragedy of Loyalty • 217 Notes • 227 Bibliography • 271 Index • 305 preface To visit the Palace of the Captain General on Havana’s Plaza de Armas today is to witness the most prominent stone- and mortar monument to the endur- ing history of Spanish colonial rule in Cuba. -

The Seal of the Unity of the Three SAMPLE

!"# $#%& '( !"# )*+!, '( !"# !"-## By the same author: Great Clarity: Daoism and Alchemy in Early Medieval China (Stanford University Press, 2006) The Encyclopedia of Taoism, editor (Routledge, 2008) Awakening to Reality: The “Regulated Verses” of the Wuzhen pian, a Taoist Classic of Internal Alchemy (Golden Elixir Press, 2009) Fabrizio Pregadio The Seal of the Unity of the Three A Study and Translation of the Cantong qi, the Source of the Taoist Way of the Golden Elixir Golden Elixir Press This sample contains parts of the Introduction, translations of 9 of the 88 sections of the Cantong qi, and parts of the back matter. For other samples and more information visit this web page: www.goldenelixir.com/press/trl_02_ctq.html Golden Elixir Press, Mountain View, CA www.goldenelixir.com [email protected] © 2011 Fabrizio Pregadio ISBN 978-0-9843082-7-9 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-9843082-8-6 (paperback) All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Typeset in Sabon. Text area proportioned in the Golden Section. Cover: The Chinese character dan 丹 , “Elixir.” To Yoshiko Contents Preface, ix Introduction, 1 The Title of the Cantong qi, 2 A Single Author, or Multiple Authors?, 5 The Dating Riddle, 11 The Three Books and the “Ancient Text,” 28 Main Commentaries, 33 Dao, Cosmos, and Man, 36 The Way of “Non-Doing,” 47 Alchemy in the Cantong qi, 53 From the External Elixir to the Internal Elixir, 58 Translation, 65 Book 1, 69 Book 2, 92 Book 3, 114 Notes, 127 Textual Notes, 231 Tables and Figures, 245 Appendixes, 261 Two Biographies of Wei Boyang, 263 Chinese Text, 266 Index of Main Subjects, 286 Glossary of Chinese Characters, 295 Works Quoted, 303 www.goldenelixir.com/press/trl_02_ctq.html www.goldenelixir.com/press/trl_02_ctq.html Introduction “The Cantong qi is the forefather of the scriptures on the Elixir of all times. -

97 Practicar 2 the King of Fighters

ROCKOLAS DE VICTORIA CONTACTO 8341135031 CELULAR Y WHATSAPP 8341135031 WWW.ROCKOLASDEVICTORIA.COM LISTA DE JUEGOS PANDORA 9H 3289 JUEGOS English Español 1 The King of Fighters '97 Practice El rey de los luchadores '97 Practicar 2 The King of Fighters '98 Practice El rey de los luchadores '98 Practicar 3 The King of Fighters '98 Combo Practice El rey de los combatientes '98 combo Practicar 4 The King of Fighters '99 Practice El rey de los luchadores '99 Practicar 5 The King of Fighters '2000 Practice El rey de los luchadores '2000 Practicar 6 The King of Fighters '2001 Practice El rey de los luchadores '2001 Practicar 7 The King of Fighters '2002 Practice El rey de los luchadores '2002 Practicar 8 The King of Fighters '2003 Practice El rey de los luchadores '2003 Practicar 9 The King of Fighters '94 El rey de los combatientes '94 10 The King of Fighters '95 El rey de los luchadores '95 11 The King of Fighters '96 El rey de los combatientes '96 12 The King of Fighters '96P lus El rey de los luchadores 96+ 13 The King of Fighters '97 El rey de los luchadores '97 14 The King of Fighters '97 10th Anniversary Chinese Edition The King of Fighters '97 décimo aniversario de la edición china 15 The King of Fighters '97 Final Battle La batalla final del rey de los combatientes '97 16 The King of Fighters '97 Oroshi Plus 2003 El rey de los luchadores '97 Oroshi Plus 2003 17 The King of Fighters '97 Plus 2003 El rey de los luchadores 97 Plus 2003 18 The King of Fighters '97 Plus The King of Fighters '97 Plus 19 The King of Fighters '97 Tu Snake The -

Mmozine Issue 9

FREE! NAVIGATE Issue 9 | January 2009 FREE FOOTBALL MANAGER LIVE FOR A YEAR + LOADS OF SEGA STUFF! + PREVIEWED Darkfall MMOZine The old school revival Free Magazine For MMO Gamers. Read it, Print it, Send it to your mates is close at hand EXCLUSIVE #1 + REVIEWED Football Manager Live It’s time to really get the EXCLUSIVE #2 season started LEADING THE CHARGE OF THE FREE! + LONG TERM TEST THE MINES OF MORIA ATLANTICA ONLINE BACK TO BASICS Delving deep inside Earth and beyond in this World Of LOTRO’s latest expansion magical combat MMOG Warcraft The Journey Begins CONTROL NAVIGATE |02 Contents WIN! QUICK FINDER DON’T MISS! A GRAPHICS Every game’s just a click away This month’s highlights… CARD! Global Agenda Darkfall Welcome Infinity: The The Chronicles Quest for Earth of Spellborn RUNES Shin Megami Lord of the to Darkfall Tensei Rings Online: When in comes to choosing an online world, OF MAGIC Enter the light Champions Online Mines of Moria most of us are happy to pay monthly charges, Horsing around for free Free Realms Football believing that a more consistent experience is Stargate Worlds Manager Live guaranteed when equal fees apply to all. The Tabula Rasa Atlantica Online misnomer over ‘free-2-play’ games is that they are Tears Saga shoddy in comparison, when the truth is that f2p EVE Online: games still require sustainable levels of investment. Apocrypha The difference is that those who can’t or won’t Runes of Magic pay are still allowed in, while those with money can pay extra and buy in-game luxuries. -

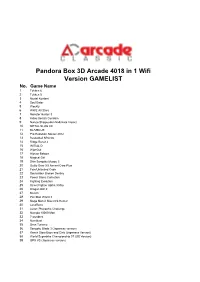

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No. Game Name 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 Soul Eater 5 Weekly 6 WWE All Stars 7 Monster Hunter 3 8 Kidou Senshi Gundam 9 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 10 METAL SLUG XX 11 BLAZBLUE 12 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 13 Basketball NBA 06 14 Ridge Racer 2 15 INITIAL D 16 WipeOut 17 Hitman Reborn 18 Magical Girl 19 Shin Sangoku Musou 5 20 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 21 Fate/Unlimited Code 22 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 23 Power Stone Collection 24 Fighting Evolution 25 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 26 Dragon Ball Z 27 Bleach 28 Pac Man World 3 29 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 30 LocoRoco 31 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 32 Numpla 10000-Mon 33 7 wonders 34 Numblast 35 Gran Turismo 36 Sengoku Blade 3 (Japanese version) 37 Ranch Story Boys and Girls (Japanese Version) 38 World Superbike Championship 07 (US Version) 39 GPX VS (Japanese version) 40 Super Bubble Dragon (European Version) 41 Strike 1945 PLUS (US version) 42 Element Monster TD (Chinese Version) 43 Ranch Story Honey Village (Chinese Version) 44 Tianxiang Tieqiao (Chinese version) 45 Energy gemstone (European version) 46 Turtledove (Chinese version) 47 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 48 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 49 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 50 Street Fighter Alpha 3 51 Street Fighter EX 52 Bloody Roar 2 53 Tekken 3 54 Tekken 2 55 Tekken 56 Mortal Kombat 4 57 Mortal Kombat 3 58 Mortal Kombat 2 59 The overlord continent 60 Oda Nobunaga 61 Super kitten 62 The battle of steel benevolence 63 Mech -

Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China

Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China ANNE BIRRELL Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824880347 (PDF) 9780824880354 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1988, 1993 Anne Birrell All rights reserved To Hans H. Frankel, pioneer of yüeh-fu studies Acknowledgements I wish to thank The British Academy for their generous Fel- lowship which assisted my research on this book. I would also like to take this opportunity of thanking the University of Michigan for enabling me to commence my degree programme some years ago by awarding me a National Defense Foreign Language Fellowship. I am indebted to my former publisher, Mr. Rayner S. Unwin, now retired, for his helpful advice in pro- ducing the first edition. For this revised edition, I wish to thank sincerely my col- leagues whose useful corrections and comments have been in- corporated into my text. -

Mandarin Over Manchu: Court-Sponsored Qing Lexicography and Its Subversion in Korea and Japan

Mandarin over Manchu: Court-Sponsored Qing Lexicography and Its Subversion in Korea and Japan Mårten Söderblom Saarela Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 77, Number 2, December 2017, pp. 363-406 (Article) Published by Harvard-Yenching Institute DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jas.2017.0030 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/682984 No institutional affiliation (1 Oct 2018 12:05 GMT) Mandarin over Manchu: Court-Sponsored Qing Lexicography and Its Subversion in Korea and Japan Mårten Söderblom Saarela 馬騰 Max Planck Institute for the History of Science anchu (Mnc.) was the official language of the Qing (Mnc. Daicing) empire. It spread to Chosŏn Korea and TokugawaM Japan largely through lexicographical compilations pro- duced in eighteenth-century Beijing to strengthen its position vis-à-vis the empire’s other languages. Those languages included the northern Chinese vernacular, Mandarin, which was also represented in these lexicographical works but in a position subordinate to the Manchu lan- guage. Korean and Japanese scholars used the Qing books to produce Abstract: The Manchu language studies of the Qing empire emerged in Beijing during the late seventeenth century and spread to Chosŏn Korea and Tokugawa Japan during the eighteenth century. The Qing court sponsored the compilation of multilingual thesauri and thereby created an imperial linguistic order with Manchu at the center and vernacular Chinese, or Mandarin, in a subordinate position. Chosŏn and Tokugawa scholars, by con- trast, usually placed Mandarin—not Manchu, Korean, or Japanese—as the leading lan- guage in the new multilingual thesauri they compiled on the basis of Qing works.