Mandarin Over Manchu: Court-Sponsored Qing Lexicography and Its Subversion in Korea and Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF (Revised Version)

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 02 July 2018 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Clements, Rebekah (2019) 'Brush talk as the 'lingua franca' of diplomacy in Japanese-Korean encounters, c. 16001868.', Historical journal., 62 (2). pp. 289-309. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0018246x18000249 Publisher's copyright statement: This article has been published in a revised form in The Historical Journal https://doi.org/10.1017/s0018246x18000249. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. c Cambridge University Press 2018. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Brush talk as ‘lingua franca’ BUSH TALK AS THE ‘LINGUA FRANCA’ OF EAST ASIAN DIPLOMACY IN JAPANESE-KOREAN ENCOUNTERS (17th-19th CENTURIES) REBEKAH CLEMENTS Durham University Abstract: The study of early modern diplomatic history has in recent decades expanded beyond a bureaucratic, state-centric focus to consider the processes and personal interactions by which international relations were maintained. -

Asia Institute Seminar December 29, 2011 Interview with Haun Saussy University Professor of Comparative Literature University Of

Asia Institute Seminar December 29, 2011 Interview with Haun Saussy University Professor of Comparative Literature University of Chicago Professor Haun Saussy is a leading scholar of Chinese and comparative literature, has been named University Professor of Comparative Literature in the Division of the Humanities and the College at the University of Chicago. One of the few figures with a deep understanding of both the Western classical and Eastern tradition, who has advanced arguments for a new global approach to comparative literature. Professor Saussy is the 17th person ever to hold the title of University Professor at University of Chicago, an honor given to distinguished scholars. Saussy's first book, The Problem of a Chinese Aesthetic (Stanford University Press, 1993), discussed the tradition of commentary that has grown up around the early Chinese poetry collection Shijing (known in English as the Book of Songs). His most recent book is Great Walls of Discourse and Other Adventures in Cultural China (Harvard University Asia Center, 2001), an account of the ways of knowing and describing specific to China scholarship. He received his B.A. (Greek and Comparative Literature) from Duke University in 1981. He received his M.Phil and Ph.D from Yale University in Comparative Literature. Saussy was previously Assistant Professor (1990-95) and Associate Professor (1995-97) at University of California, Los Angeles. He was Associate Professor, Full Professor, and chairman of the comparative literature department at Stanford University, prior to joining the Yale faculty in 2004. Emanuel Pastreich: We both began in Nashville, Tennessee, and we both had fathers involved in music. -

2012-13 Annual Report

East Asian Studies Program and Department Annual Report 2012-2013 Table of Contents Director’s Letter .....................................................................................................................................................................1 Department and Program News .............................................................................................................................................2 Losses and Retirements .....................................................................................................................................................2 Department and Program News ........................................................................................................................................4 Departures .........................................................................................................................................................................4 Language Programs ...........................................................................................................................................................4 Thesis Prizes ......................................................................................................................................................................5 EAS Department Majors .................................................................................................................................................. 6 EAS Language and Culture Certificate Students ..............................................................................................................6 -

Murakami Haruki and an Emergent Japanese Cosmopolitan Identity

Beyond cultural nationalism: Murakami Haruki and an emergent Japanese cosmopolitan identity Tomoki Wakatsuki A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Acknowledgements I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisor, Associate Professor Dr. Paul Jones, without whom I could not have completed a doctoral thesis. His extensive knowledge of cultural studies, cultural sociology and media studies inspired me throughout this journey. I am grateful for his professional guidance and for saving me from drowning in a sea of uncertainties. I am indebted to my co-supervisor Dr. Claudia Tazreiter whose encouraging and constructive feedback was instrumental in the development of my thesis. Her suggestion of cosmopolitanism invigorated my exploration of contemporary Japanese society. I would also like to thank my editor Dr. Diana Barnes for helping me to produce the final draft. My sincere thanks go to Maria Zueva at the Learning Centre of the University of New South Wales who supported my writing. I would like to thank the School of Sociology at the University of New South Wales for providing me this opportunity. The university’s excellent library system allowed me to complete my studies from Japan. The Graduate Research School gave generous support to my research while I was overseas. My deepest appreciation goes to Kyung-Ae Han for sharing the long journey with me, while we were both in Sydney and later when we were in Seoul and Tokyo. Thank you for reading countless drafts and providing valuable feedback. -

Participants Nautilus Seoul Workshop

Participants Nautilus Seoul Workshop from China Deng, Quheng (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) Deng Quheng got his Ph.D. degree in economics from the Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Since 2003, he has worked in the Institute of Economics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. His research fields include development economics, labor economics and applied microeconometrics. From 2004 to 2008, he conducted cooperative research at University of Oxford in U.K., University of Gothenburg and National Social Insurance Board in Sweden, Paris School of Economics and University Lyon II in France. His English language publications appear in China Perspectives and a forthcoming issue of CESifo Economic Studies, apart from dozens of papers published in Chinese. He also serves as referee of CESifo Economic Studies and World Development. Han, Hua (Beijing University) HAN Hua is Associate Professor and Director of the Center for Arms Control and Disarmament at the School of International Studies (SIS), Peking University, China. She is an expert on, and teaches courses in International Arms Control, Disarmament and Nonproliferation, US Foreign Policy in Asia Pacific, and nuclear-related issues in South Asia. Han Hua has been a visiting researcher at School of International Affairs, Georgia Institute of Technology, USA, The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Sweden, The Stimson Center and Monterey Center for Nonproliferation in Washington DC, The Victoria University, Canada, and the Peace and Conflict Institute, Uppsala University, Sweden. She has also written extensively on Arms Control, nonproliferation and China's foreign policy for journals and newspapers in China and abroad. 1 Wang, Yanjia (Tsinghua University) Ms. -

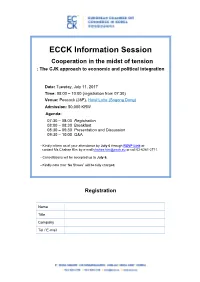

ECCK Information Session

ECCK Information Session Cooperation in the midst of tension : The CJK approach to economic and political integration Date: Tuesday, July 11, 2017 Time: 08:00 – 10:00 (registration from 07:30) Venue: Peacock (36F), Hotel Lotte (Sogong Dong) Admission: 50,000 KRW Agenda: 07:30 – 08:00 Registration 08:00 – 08:30 Breakfast 08:30 – 09:30 Presentation and Discussion 09:30 – 10:00 Q&A - Kindly inform us of your attendance by July 6 through RSVP Link or contact Ms Chahee Kim by e-mail [email protected] or call 02-6261-2711. - Cancellations will be accepted up to July 6. - Kindly note that “No Shows” will be fully charged. Registration Name Title Company Tel / E-mail Speakers Emanuel Pastreich writes extensively on culture, technology, the environment and international relations with a focus on Northeast Asia. He serves as a professor at Kyung Hee University’s College of International Studies and as the director of the Asia Institute in Seoul, Korea. Pastreich majored in Chinese at Yale University (1987) and received an M.A. in comparative literature at the University of Tokyo (1992), where he did all coursework in Japanese. After receiving a Ph.D. at Harvard University (1997) he started teaching at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign as a professor of Japanese literature. His research focused on the reception of Chinese vernacular narrative in Emanuel Pastreich Korea and Japan in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a topic Director, The Asia about which he has written two books. Institute Pastreich served as the director of the KORUS House (2005-2007), a Associate policy think tank operated in the embassy of the Republic of Korea in Professor, Kyung Washington D.C. -

ACDIS Occasional Paper

ACDIS Occasional Paper Sovereignty, Wealth, Culture, and Technology: Mainland China and Taiwan Grapple with the Parameters of "Nation State" in the 21st Century Emanuel Pastreich Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Research of the Program in Arms Control, Disarmament, and International Security University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign July 2003 This publication is supported by funding from the University of Illinois and is produced by the Program m Arms Control Disarmament and International Security at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign The University of Illinois is an equal opportunity/ affirmative action institution ACDIS Publication Senes ACDIS Swords and Ploughshares is the quarterly bulletin of ACDIS and publishes scholarly articles for a general audience The ACDIS Occasional Paper senes is the principal publication to arcuiate the research and analytical results of faculty and students assoaated with ACDIS The ACDIS Research Reports senes publishes the results of grant and contract research Publications of ACDIS are available upon request For additional information consult the ACDIS home page on the World Wide Web at <http //w w w acdis uiuc edu/> Published 2003 by ACDIS/ / ACDIS PAS 12003 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 359 Armory Building 505 E Armory Ave Champaign IL 61820-6237 Sovereignty, Wealth, Culture, and Technology: Mainland China and Taiwan Grapple with the Parameters of “Nation State” in the 21st Century Emanuel Pastreich East Asian Languages -

Prof. Emanuel Pastreich

Prof. Emanuel Pastreich 1. Contact Information - Name: Pastreich, Emanuel - Position: Associate Professor - Major: Comparative Culture - Office: Room 417, International Studies Building - Phone Number: +82-31-201-3885 - Fax Number: +82-31-204-8120 - E-mail: [email protected] 2. Detail Ⅰ. Introduction Emanuel Pastreich focuses on the intersection of cultural and historical issues with current policy in East Asia with a focus on the environment and international relations. His original training was in comparative Asian literature and he has published extensively on the reception of Chinese narrative in Korea and Japan. More recently, Pastreich has written on the security implications of climate change, Korean culture and society and prospects for cooperation between the nations of East Asia. He serves as the director of the think tank Asia Institute (asia-institute.org) in Seoul. 1. Contact Information - Office: Room 416, International Studies Building - Phone Number: +82-31-201-3885 - Fax Number: +82-31-204-2281 - E-mail: [email protected] 2. Educational Background - Ph.D. in East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1998 - M.A. in Comparative Literature, University of Tokyo, 1992 - B.A. in Chinese Literature, Yale College, 1987 3. Areas of Expertise Chinese, Japanese & Korean literature Science and research policy Science and Technology in Society Comparative Asian culture - Courses Taught “History of East Asia” “Understanding Asian Culture” “Novels of Park Jiwon” “Technology and Society” Ⅱ. Professional Experiences (From the recent -

Is There a Long-Term Solution to the Senkaku-Diaoyu Islands Conflict?

OMNES : The Journal of Multicultural Society 2017, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 154-189, http://dx.doi.org/10.15685/omnes.2017.01.7.2.154 ❙Article❙ The Problem with Islands: Is There a Long-term Solution to the Senkaku-Diaoyu Islands Conflict? Emanuel Pastreich Abstract The article traces the history of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands and explores the underlying reasons why they have become the site of a political dispute between China and Japan. The paper suggests that islands have a specific ambiguity to them that makes them an easy space on to which to project political power and insecurity. Stress is placed on the changing concepts of geographical space that complicate what might otherwise have been a minor disagreement over islands and suggests how cultural factors have made uninhabited islands into a hot button issue that determines military budgets. The final section of the paper makes concrete suggestions as to how the conflict might be defused through cultural exchange and a broader conception of local issues. The author suggests that efforts to promote codependence and highlight local issues could make a difference because they will bring the focus of attention to the local communities. ❚Keywords:Senkaku Islands, Japanese foreign policy, Okinawa, Daiyu Islands, Pacific Pivot, Okinawa Introduction Much ink has been spilled in the media in the narration of the dispute between Japan and China about the sovereignty of an obscure group of islands known as the Senkaku Islands (or Diaoyu Islands in Chinese). Although there has been much discussion about how this dispute repre- sents the “aggressiveness” of a “rising China,” or the “assertiveness” of a reinvigorated Japan, remarkably little attention has been given to the cultural and historical background of the islands, or the ideological and OMNES : The Journal of Multicultural Society|2017. -

Download The

! OGYŪ SORAI, HUMAN NATURE, AND EDO SOCIETY: THE CHINESE CONTEXT ! ! by ! MINORU TAKANO ! ! ! ! ! ! A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF ! MASTER OF ARTS ! ! in ! ! THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES ! (Asian Studies) ! ! ! THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA ! (Vancouver) ! ! April 2014 ! ! ! ! ! ©Minoru Takano, 2014 Abstract This thesis deals with the prevailing image of Ogyū Sorai 荻生徂徠 (1666-1728) as a pioneer who proposed to read Chinese classics not in the Japanese way of kundoku 訓読 but in its original way, i.e. in the Chinese word order and pronunciation. I challenge the historical accuracy of this image and regard it as a product created mainly by the prominent Japanese Sinologist, Yoshikawa Kōjirō 吉川幸 次郎 (1904-1980). It is well known that Sorai stressed the importance of rites, music, punishments and administration 禮樂刑政 as external forces which transform the internal mind from the outside. I believe that Sorai stressed mastery of literary style rather than mastery of colloquial Chinese as an external thing 物. His belief in practicality which was cultivated by the art of war led Sorai to attempt to realize a world based on a rigid meritocratic hierarchy. Therefore, Sorai proposed to return to the literary styles of the Qin, Han and Tang dynasties whose political situations were highly centralized. This, he believed, would serve to transform the feudalistic hereditary Neo-Confucian Edo state composed of Shogun and Daimyo into a more centralized and meritocratic one through educational policy. In pre-modern China, literature and politics were thought to be connected closely. Previous research, however, had been centered around literary studies focusing on the influence of the Guwenci pai 古文辭派 (Old Phraseology School) upon Sorai’s Kobunji 古文辭 (Ancient Words and Phrases) school. -

Wrestling with Shadows

Wrestling with Shadows A Novel by Emanuel Pastreich This novel is entirely fictional and no part of its content is based on actual events or on the actions of actual individuals, living or dead. 1 Wrestling with Shadows Copyright 2021 2 Wrestling with Shadows CONTENTS Introduction page 9 Chapter 1 page 17 Chapter 2 page 53 Chapter 3 page 87 Chapter 4 page 113 Chapter 5 page 132 Chapter 6 page 148 Chapter 7 Page 177 Conclusion page 186 Appendix page 192 University of Illinois proposal page 192 University of Tokyo proposal Page 202 Peking University proposal page 210 Seoul National University proposal Page 214 3 4 Summary Emanuel Pastreich was an ambitious assistant professor at the University of Illinois when he happened to attend a demonstration of the on-line learning technology that was being developed there in April 2000. Within a few weeks, he had put together a proposal for shared courses on-line, for joint research and for other institutional collaboration between University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign and the leading research institutes in East Asia: University of Tokyo, Seoul National University and Peking University. Seeing such an unprecedented approach to on-line learning as a tremendous opportunity, he threw himself into the project. Pastreich had a strong command of the Chinese, Japanese and Korean languages form his training in Asian studies and his personal connections with top administrators and professors at the major universities in China, Japan and Korea allowed him to advance his ideas rapidly. He did not seek any personal financial benefit, and did not seek to promote himself, thus making the process far more easy. -

New Items – January 2017

New Items – January 2017 Ebooks and Electronic Theses are displayed as [electronic resource] Including books from previous years in special collections added to the Music Library Vasserman, Rinat author. Structure-function investigation of srGAP2 [electronic resource] / Rinat Vasserman. 2015 (002419058 ) Brain. Bar Ilan University -- Dissertations -- Department of Life Sciences GTPase-activating protein. .אוניברסיטת בר-אילן -- עבודות לתאר שני -- הפקולטה למדעי החיים Fromovich, Shay author. Commanders influence & optimal medical treatment in a military base [electronic resource] / Shay Fromovich. 2015 (002422774 ) Medicine, Military -- Israel (State). Bar Ilan University -- Dissertations -- Dept. of Managment Military bases -- Israel (State). .אוניברסיטת בר אילן -- עבודות לתאר שני -- המחלקה לנהול Matlahov, Irina author. Interfacial mineral [electronic resource] : peptide properties of Osteonectin's N=terminal domain and bone-like apatite and its impact on the morphology of apatite / Irina Matlahov. 2016 (002429157 ) Mineralogical chemistry. Apatite in the body. Bar Ilan University -- Dissertations -- Department of Chemistry .אוניברסיטת בר-אילן -- עבודות לתאר שלישי -- המחלקה לכימיה Bachvarova, Mary R author. From Hittite to Homer [electronic resource] : the Anatolian background of ancient Greek epic / Mary R. Bachvarova. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2016. (002436269 ) Homer.. Ilias Epic poetry, Greek -- History and criticism. Hittites -- Religion. Gilgamesh. Hittite literature -- History and criticism. Simon, Barry, 1946- author. A comprehensive course in analysis [electronic resource] / Barry Simon. Providence, Rhode Island : American Mathematical Society, [2015] (002437587 ) Mathematical analysis -- Textbooks. Yoder, Tyler R author. Fishers of fish and fishers of men [electronic resource] : fishing imagery in the Hebrew Bible and the ancient Near East / Tyler R. Yoder. Winona Lake, Indiana : Eisenbrauns, 2016 (002438626 ) Metaphor in the Bible. Symbolism in the Bible.