Caring for Ontario's Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critical Analysis of the Media's Coverage of Religious

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7-25-2012 12:00 AM Moving Beyond the “Mosqueteria:” A Critical Analysis of the Media’s Coverage of Religious Accommodation at an Ontario Public School Aruba Mahmud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Goli Rezai-Rashti The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Education A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Education © Aruba Mahmud 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Education Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post- Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mahmud, Aruba, "Moving Beyond the “Mosqueteria:” A Critical Analysis of the Media’s Coverage of Religious Accommodation at an Ontario Public School" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 648. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/648 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moving Beyond the “Mosqueteria:” A Critical Analysis of the Media’s Coverage of Religious Accommodation at an Ontario Public School Spine title: Moving Beyond the “Mosqueteria” (Thesis format: Monograph) by Aruba Mahmud Graduate Program in Education A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Aruba Mahmud 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORATE STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ ______________________________ Dr. -

Converting Quebec's Strengths Into Prosperity

www.td.com/economics CONVERTING QUEBECS STRENGTHS INTO PROSPERITY Executive Summary Few economies in North America have undergone the stitute looks at a number of measurable elements of pro- degree of post-War change as Quebec, beginning with the ductivity in its study, including the mix of industries, edu- Quiet Revolution in the 1960s. The reforms have borne cation attainment, the degree of urbanization and how much fruit over the past half century. Quebec enjoys a high investment in machinery and infrastructure take place in quality of life, its culture and language have flourished and an economy. the income gap in the province between Francophones and Interestingly, while there tends to be considerable at- Anglophones has all but been eliminated. Whats more, tention placed on Quebecs productivity gap with the Quebec has built up an enviable list of assets a highly- ROC, the Institute determined that output per hour worked diversified economy and high quality of life to name a few explains only 38% of the difference in prosperity, of which that will stand the province in good stead in the future. three-quarters is attributable to industry mix, education at- Yet there have been growing calls within Quebec for tainment and capital investment. residents and businesses to embrace change once again. In spite of its numerous strengths, the provinces standard What are the trade-offs in working less? of living as measured by GDP per capita continues to At the same time, 62% of the prosperity gap is ex- languish behind that of the rest of Canada (ROC). But the plained by reduced hours worked. -

Master of Arts in History, Queen's University. Super

Dr. Christos Aivalis SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow Department of History University of Toronto Education: 613-929-4550 [email protected] 2010-2015: Ph.D. in History at Queen’s University 2009-2010: Master of Arts in History, Queen’s University. Supervisor: Ian McKay. 2005-2009: Bachelor of Arts (hons.) in History and Political Science, University of New Brunswick. Dissertation: “Pierre Trudeau, Organized Labour, and the Canadian Social Democratic Left, 1945-2000.” Supervisor: Ian McKay. Committee members: Timothy Smith, Jeffery Brison, Pradeep Kumar, and Gregory Kealey. Post-Graduate Scholarships and Awards: 2017- 2019: SSHRC Post-Doctoral Fellowship Award (held at the University of Toronto, Department of History. Supervisor: Dr. Sean Mils 2016-17: Nominee—Eugene Forsey Prize in Canadian Labour and Working-Class History— Best Graduate Thesis 2016: Queen’s University Department of History’s most Outstanding Doctoral Dissertation Prize 2016: Queen’s University Award for Scholarly Research and Creative Work and Professional Development 2016: Departmental Nominee—John Bullen Prize for Canadian Historical Association’s best Doctoral Dissertation 2015: Nominee—Canadian Committee for Labour History Article Prize. 2015: Nominee—New Voices in Labour Studies—Best Paper Prize. 2015: Nominee—Jean-Marie-Fecteau Prize for Canadian Historical Association’s Best Graduate Student Article. 2013-2015: Queen’s University Graduate Scholarship. 2013-2014: Finalist—Queen’s University History Department Teaching Award. 2010-2013: SSHRC Joseph-Armand Bombardier CGS Doctoral Scholarship. 2010: Queen’s University Tri-Council Award. 2010: Ontario Graduate Scholarship (declined). 2009: SSHRC Master's Scholarship. 2009: Queen’s University Tri-Council Award. Teaching and Research Experience: Fall 2018-Winter 2019: Adjunct Professor for History 102: History of Canada, Royal Military College of Canada. -

Asper Nation Other Books by Marc Edge

Asper Nation other books by marc edge Pacific Press: The Unauthorized Story of Vancouver’s Newspaper Monopoly Red Line, Blue Line, Bottom Line: How Push Came to Shove Between the National Hockey League and Its Players ASPER NATION Canada’s Most Dangerous Media Company Marc Edge NEW STAR BOOKS VANCOUVER 2007 new star books ltd. 107 — 3477 Commercial Street | Vancouver, bc v5n 4e8 | canada 1574 Gulf Rd., #1517 | Point Roberts, wa 98281 | usa www.NewStarBooks.com | [email protected] Copyright Marc Edge 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (access Copyright). Publication of this work is made possible by the support of the Canada Council, the Government of Canada through the Department of Cana- dian Heritage Book Publishing Industry Development Program, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit. Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Printing, Cap-St-Ignace, QC First printing, October 2007 library and archives canada cataloguing in publication Edge, Marc, 1954– Asper nation : Canada’s most dangerous media company / Marc Edge. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-1-55420-032-0 1. CanWest Global Communications Corp. — History. 2. Asper, I.H., 1932–2003. I. Title. hd2810.12.c378d34 2007 384.5506'571 c2007–903983–9 For the Clarks – Lynda, Al, Laura, Spencer, and Chloe – and especially their hot tub, without which this book could never have been written. -

Rubrique 1: Développement Communautaire

Veille – semaine du 15 janvier 2012 1. GOUVERNANCE ET ENGAGEMENT COMMUNAUTAIRES Ontario – Francophonie 16 janvier 2012 - Les États généraux de la francophonie d’Ottawa ont le plaisir de vous convier à leurs premiers Cafés citoyens, qui marqueront le début d’une vaste consultation publique communautaire. Ces Cafés vous offriront l’occasion toute particulière d’imaginer le devenir de la communauté francophone d’Ottawa. Venez partager vos ambitions, vos rêves et vos idées pour une francophonie plus forte et plus dynamique à Ottawa. Pendant plusieurs mois, et dans différents lieux reconnus de la communauté, les Cafés citoyens viseront à identifier les enjeux qui touchent la francophonie ottavienne. Ils permettront aussi une réflexion sur les différentes pistes d’action et sur les mécanismes à mettre en œuvre pour qu’elle puisse décider de son avenir comme collectivité. Les idées et les propositions qui résulteront de ces consultations viendront nourrir directement les travaux du Sommet 2012, évènement qui marquera les assises officielles des États généraux. http://www.francophoniecanadienne.ca/main+fr+01_200+Invitation_aux_premiers_Cafes_citoye ns_des_Etats_generaux_de_la_francophonie_dOttawa.html?AnnonceCatID=8&AnnonceID=154 6 18 janvier 2012 - L’Association des communautés francophones de l’Ontario (ACFO) à Toronto a tenu son assemblée générale le lundi 9 janvier, un nouveau conseil d’administration (CA) de 11 membres a été nommé (par rapport à 6 auparavant). À l’issue de l’assemblée générale, le CA a élu le président de l’organisme, Gilles Marchildon (également directeur des programmes d’Action Positive VIH/Sida), la vice-présidente, Céline Saday, ainsi que le secrétaire, le politologue Alexandre Brassard. Au poste de trésorier, le CA a choisi la stabilité en reconduisant Marcel Grimard, président de l’ACFO Toronto il y a quelques années. -

Fraser Forum

Table of Contents Articles Focus 3 Up Front: Ezra Levant speaks freely 6 Why are Quebec’s students failing? The former Western Standard publisher discusses his Peter Cowley battle with the Alberta Human Rights Tribunal which The exam failure rates in Quebec’s public schools—which ended 900 days after it began. account for roughly 82% of the province’s secondary school enrollment—are more than double those of private schools 8 Self-interest benefits everyone in all subjects except basic mathematics. Niels Veldhuis Self-interested individuals and businesses are the 7 Quebec’s agriculture in jeopardy backbone of our economy, vital to economic progress Jean-Francois Minardi and the well-being of society. To ensure the viability of Quebec’s agricultural sector, the province should phase out its supply management regime 9 Measuring entrepreneurship and eliminate farm subsidies. Keith Godin & Niels Veldhuis The Canadian provinces trail the US states on six different 21 Cars and climate change measures of entrepreneurship. Diane Katz The government of Quebec is preparing to impose the 13 Canada’s physician supply nation’s most stringent regulations on auto emissions. But Nadeem Esmail these regulations are more likely to endanger lives than The current supply is insufficient to meet the demand change the climate. for physician care and falls well short of what is being 29 Water rights under threat in Quebec delivered in other developed nations with similar Diane Katz & Jean-Francois Minardi approaches to health care. Bill 92, if enacted, will rob Quebecers of their property rights and discourage investment in the province. -

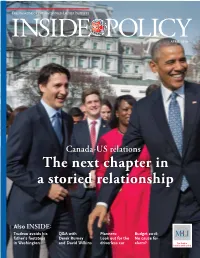

The Next Chapter in a Storied Relationship

APRIL 2016 Canada-US relations The next chapter in a storied relationship Also INSIDE: Trudeau avoids his Q&A with Planners: Budget 2016: father’s footsteps Derek Burney Look out for the No cause for in Washington and David Wilkins driverless car alarm? PublishedPublished by by the the Macdonald-Laurier Macdonald-Laurier Institute Institute PublishedBrianBrian Lee Lee Crowley, byCrowley, the Managing Macdonald-LaurierManaging Director,Director, [email protected] [email protected] Institute David Watson,JamesJames Anderson,Managing Anderson, Editor ManagingManaging and Editor, Editor,Communications Inside Inside Policy Policy Director Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] James Anderson,ContributingContributing Managing writers:writers: Editor, Inside Policy Past contributors ThomasThomas S. AxworthyS. Axworthy ContributingAndrewAndrew Griffith writers: BenjaminBenjamin Perrin Perrin Thomas S. AxworthyDonald Barry Laura Dawson Stanley H. HarttCarin Holroyd Mike Priaro Peggy Nash DonaldThomas Barry S. Axworthy StanleyAndrew H. GriffithHartt BenjaminMike PriaroPerrin Mary-Jane Bennett Elaine Depow Dean Karalekas Linda Nazareth KenDonald Coates Barry PaulStanley Kennedy H. Hartt ColinMike Robertson Priaro Carolyn BennettKen Coates Jeremy Depow Paul KennedyPaul Kennedy Colin RobertsonGeoff Norquay Massimo Bergamini Peter DeVries Tasha Kheiriddin Benjamin Perrin Brian KenLee Crowley Coates AudreyPaul LaporteKennedy RogerColin Robinson Robertson Ken BoessenkoolBrian Lee Crowley Brian Dijkema Audrey LaporteJeremy Kinsman Roger RobinsonJeffrey -

Mnc2020 Program

March 26-28, 2020 MNC2020 PROGRAM Thursday, March 26th, 2020 6:00PM 6:15PM Video Presentation and Welcome Remarks Provinces I/II & Confederation I Troy Lanigan - President, Manning Centre Rodney MacDonald - Presenting Debate Sponsor, Intuit Canada 6:15PM 8:00PM Conservative Party of Canada Leadership Candidates Debate • Marilyn Gladu • Rudy Husny • Jim Karahalios • Dr. Leslyn Lewis • Peter MacKay • Erin O’Toole • Rick Peterson • Derek Sloan Moderators: Tasha Kheiriddin and Danielle Smith NOTE: Only those candidates which have met LEOC’s verified criteria as of the final March 25th cutoff will participate in the debate the following day. Candi- dates above have signalled their intention to participate in the debate at the time of publication of this agenda. 8:00PM 11:00PM Networking Reception Governor General Ballroom I, II & III 8:50PM Air Canada Draw Governor General Ballroom I, II & III 9:00PM 11:00PM Marilyn Gladu Hospitality Suite Nova Scotia & Newfoundland Rooms Friday, March 27th, 2020 7:00AM 8:30AM Breakfast Confederation II/III 8:30AM 8:40AM What’s Next for the Manning Centre Provinces I/II & Confederation I • Preston Manning - Founder 8:45AM 9:30AM Keynote and Fireside Chat Provinces I/II & Confederation I • The Hon. Dennis King - Premier of Prince Edward Island Introduction: Jackson Doughart Moderator: Charelle Evelyn - Managing Editor of The Hill Times 9:30AM 10:30AM What’s Next for National Unity: A Look at the State of the Federation Provinces I/II & Confederation I • The Hon. Christy Clark - Former Premier of British Columbia • The Hon. Preston Manning - Founder and Leader of the Reform Party of Canada • Sen. -

Culture in the Balance

Culture in the Balance Analyses of the Provincial and Territorial 2014-2015 Budgets from the Perspective of Arts, Culture and Heritage Centre on Governance, University of Ottawa Notes All provincial and territorial real GDP growth statistics were retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/141105/dq141105a-eng.htm All figures on federal transfers as a percentage of provincial’ and territorial revenues were retrieved from http://www.fin.gc.ca/fedprov/mtp-eng.asp All provincial and territorial population figures were retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/demo02a-eng.htm The views expressed in this analysis are those of the authors, and not those of the Centre on Governance or the University of Ottawa. 2015 i Acknowledgements This document was produced on a volunteer basis with the help and support of the following individuals: Co-authors M. Sharon Jeannotte Alain Pineau Research Betsy Leimbigler Publishing Angela Francovic Annie Charlebois ii Foreword I am happy to present to you the analyses of the 2014-15 provincial and territorial budgets from the perspective of arts, culture and heritage. This initiative was originally launched in 2012 by the Canadian Conference of the Arts (CCA) in partnership with the Centre on Governance. Unfortunately, the CCA was forced to suspend its operations in late 2012 due to the loss of the financial support it used to get from the Department of Canadian Heritage. However, thanks to the volunteer work of M. Sharon Jeannotte, Senior Fellow at the Centre, and of Alain Pineau, former National Director of the CCA, and the collaboration of University of Ottawa students, we were able to produce a second abbreviated version of the Analyses in 2013, and are now pleased to present a third edition. -

Housing and Transportation in Montreal

Montreal Economic Institute Research Papers 7i`iÊ Ý ÕÃ}Ê>`Ê/À>ëÀÌ>ÌÊÊÌÀi> ÜÊÃÕLÕÀL>â>ÌÊÃÊ«ÀÛ}ÊÌ iÊÀi}½ÃÊV«iÌÌÛiiÃà ÕÞÊÓääÈ - ÊÓÓÓÈnǣǣ Wendell Cox Housing and Transportation in Montreal How suburbanization is improving the region’s competitiveness Montreal Economic Institute Research Paper • July 2006 Chairman of the Board: Adrien D. Pouliot Acting President : Tasha Kheiriddin The Montreal Economic Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-profit, non- 6708 Saint-Hubert Street partisan research and educational institute. It endeavours to promote an Montreal, Quebec economic approach to the study of public policy issues. Canada H2S 2M6 The MEI is the product of a collaborative effort between entrepreneurs, Telephone: (514) 273-0969 academics and economists. The Institute does not accept any public Fax: (514) 273-2581 funding. Web site: www. iedm.org The MEI is a registered charity as defined by the applicable federal and provincial statutes. Therefore, it issues receipts for income tax purposes. One-year subscription to the MEI publications : $98.00. The opinions expressed in this study do not necessarily represent those of the Montreal Economic Institute or of the members of its board of directors. The publication of this study in no way implies that the Montreal Economic Institute or the members of its board of directors are in favour of or oppose the passage of any bill. Production supervision: MB Conseil Cover, cover photos, design and typesetting: Guy Verville © 2006 Montreal Economic Institute ISBN 2-922687-17-1 Legal deposit: 2th quarter 2006 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec Library and Archives Canada Printed in Canada Housing and Transportation in Montreal Table of contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... -

Creations Rich and Strange Revisiting Artists from Lawren Harris to Joni Mitchell by John Lownsbrough, Molly Peacock, Carl Wilson and Many Others

What harm is hate speech? PAGE 16 $6.50 Vol. 21, No. 1 January/February 2013 Creations Rich and Strange Revisiting artists from Lawren Harris to Joni Mitchell By John Lownsbrough, Molly Peacock, Carl Wilson and many others ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Madelaine Drohan Roger Gibbins Donald Akenson Boomtime saving Western upstarts vs. The other Acadian exile Publications Mail Agreement #40032362 or bust eastern bastards Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to LRC, Circulation Dept. PO Box 8, Station K Toronto, ON M4P 2G1 …AND MUCH MORE! Buy 2 subscriptions, get 1 FRee. Nearly 200 titles! Don’t miss the Annual Great Magazine Sale. ORDER NOW! Subscribe today at 1free.magazinescanada.ca/3for2 or call 1-866-289-8162 OffER cODE: PAEB Keep all 3 subscriptions for yourself or GIVE some as a gift. Choose print or digital subscriptions. With this much selection it’s easy to find the perfect titles to read or share. 12044_MagsCanada_ad_standard.indd 1 12-09-18 2:19 PM Literary Review of Canada 170 Bloor St West, Suite 710 Toronto ON M5S 1T9 email: [email protected] reviewcanada.ca T: 416-531-1483 • F: 416-531-1612 Charitable number: 848431490RR0001 To donate, visit reviewcanada.ca/support Vol. 21, No. 1 • January/February 2013 Editor Bronwyn Drainie [email protected] Contributing EditorS 3 Spending Like There’s 16 Public Hostility 24 Defiant Individualism Mark Lovewell No Tomorrow A review of The Harm in Hate A review of My Life on Earth Molly Peacock Anthony Westell An essay Speech, by Jeremy Waldron and Elsewhere, by R. Murray ASSoCiAtE Editor Madelaine Drohan Michael Plaxton Schafer Robin Roger Colin Eatock 6 After Le grand 18 Picasso at 90 PoEtry Editor dérangement A poem 25 Patrician Bohemianism Moira MacDougall A review of The Acadian Merle Nudelman A review of Inward Journey: CoPy Editor Madeline Koch Diaspora: An Eighteenth- 18 Hung Jury, Sable The Life of Lawren Harris, by Century History, by James King onlinE EditorS Island Maria Tippett Diana Kuprel, Jack Mitchell, Christopher Hodson A poem Donald Rickerd, C.M. -

Inside Policy REV3.Indd 1 27/11/12 4:47 PM We Take the Lead, and We Deliver

DECEMBER 2012 ~ JANUARY 2013 VOLUME 1 NUMBER 2 Mark Carney Policy Maker of the Year The Northern Gateway Project will deliver energy to the world, as well as signifi cant economic benefi ts for Canada. Northern Gateway is generating healthy debate and Canadians are asking, what are the benefi ts of this pipeline for our country? The Northern Gateway Project will create jobs, open up a new gateway to trade partners in the Pacifi c Rim, and strengthen Canada’s economy. New jobs will be created… Many people will be employed to build this project. Over 3,000 high-paying construction jobs will be created during the building phase. And over 1,150 new long-term jobs will open up when it’s completed–jobs to monitor and maintain the pipeline, jobs at the Marine Terminal on BC’s north coast, and indirect jobs in areas such as food and hospitality, accommodations, and transportation. New global markets will open opportunities for new growth… As it stands, Canada relies on just one customer for its oil exports. The Northern Gateway Project will provide access to the growing economies and the huge markets of the Pacifi c Rim eager for our energy, which will increase Canada’s Gross Domestic Product by at least $270 billion over 30 years. So not only will Canadians see an increase in employment and long-term job opportunities, they will see our country’s economy strengthened as a new gateway to more trade partners opens up. People will learn specialized work skills… Canadians will be given the opportunity to learn the skills needed to work in the energy industry.