Spectatorship, Affect, and Gender in the Slasher Cycle Snow Marti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

How to Die in a Slasher Film: the Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol

Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Copyright © 2021 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN: 1070-8286 How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization, Strength, and Flaws on Characters’ Mortality Ashley Wellman Texas Christian University & Michele Bisaccia Meitl Texas Christian University & Patrick Kinkade Texas Christian University 128 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Abstract Popular culture has often referenced formulaic ways to predict a character’s fate in slasher films. The cliché rules have noted only virgins live, black characters die first, and drinking and drugs nearly guarantee your death, but to what extent do characters’ basic demographics and portrayal determine whether a character lives or dies? A content analysis of forty-eight of the most influential slasher films from the 1960s – 2010s was conducted to measure factors related to character mortality. From these films, gender, race, sexualization (measured via specific acts and total sexualization), strength, and flaws were coded for 504 non killer characters. Results indicate that the factors predicting death vary by gender. For male characters, those appearing weak in terms of physical strength or courage and those males who appeared morally flawed were more likely to die than males that were strong and morally sound. Predictors of death for female characters included strength and the presence of sexual behavior (including dress, flirtatious attitude, foreplay/sex, nudity, and total sexualization). -

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

Sex, Violence and the Body: the Erotics of Wounding

Sex, Violence and the Body The Erotics of Wounding Edited by Viv Burr and Jeff Hearn PPL-UK_SVB-Burr_FM.qxd 9/24/2008 2:33 PM Page i Sex, Violence and the Body PPL-UK_SVB-Burr_FM.qxd 9/24/2008 2:33 PM Page ii Also by Viv Burr AN INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONISM GENDER AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY INVITATION TO PERSONAL CONSTRUCT PSYCHOLOGY (with Trevor W. Butt) THE PERSON IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY Also by Jeff Hearn BIRTH AND AFTERBIRTH: A Materialist Account ‘SEX’ AT ‘WORK’: The Power and Paradox of Organisation Sexuality (with Wendy Parkin) THE GENDER OF OPPRESSION: Men, Masculinity and the Critique of Marxism MEN, MASCULINITIES AND SOCIAL THEORY (co-editor with David Morgan) MEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE: The Construction and Deconstruction of Public Men and Public Patriarchies THE VIOLENCES OF MEN: How Men Talk about and How Agencies Respond to Men’s Violence to Women CONSUMING CULTURES: Power and Resistance (co-editor with Sasha Roseneil) TRANSFORMING POLITICS: Power and Resistance (co-editor with Paul Bagguley) GENDER, SEXUALITY AND VIOLENCE IN ORGANIZATIONS: The Unspoken Forces of Organization Violations (with Wendy Parkin) ENDING GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE: A Call for Global Action to Involve Men (with Harry Ferguson et al.) INFORMATION SOCIETY AND THE WORKPLACE: Spaces, Boundaries and Agency (co-editor with Tuula Heiskanen) GENDER AND ORGANISATIONS IN FLUX? (co-editor with Päivi Eriksson et al.) HANDBOOK OF STUDIES ON MEN AND MASCULINITIES (co-editor with Michael Kimmel and R. W. Connell) MEN AND MASCULINITIES IN EUROPE (with Keith Pringle et al.) -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

Read an Excerpt

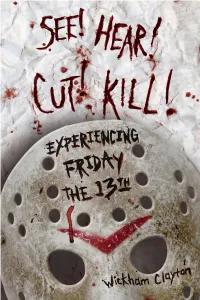

Univer�it y Pre� of Mis �is �ipp � / Jacks o� Contents u Preface: This book could be for you, depending on how you read it . ix. Acknowledgments . .xiii Chapter 1 Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy . 3 Chapter 2 Jason’s Mechanical Eye . 45 Chapter 3 Hearing Cutting . .83 . Chapter 4 Have You Met Jason? . 119. Chapter 5 The Importance of Being Jason . 153 .. Appendix 1 Plot Summaries for the Friday the 13th Films . 179 Appendix 2 List and Description of Characters in the Friday the 13th Films . 185 Works Cited . 199 Index . 217. Chapter 1 u Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy Sometimes the weirdest movies strike you in unexpected ways. In the winter of 1997, I attended a late-night screening of Friday the 13th (1980) at the campus theater at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. I’d never seen the film before, but I was aware of its cultural significance. I expected a generic slasher film with extensive violence and nudity. I expected something ultimately forgettable. Having watched it seventeen years after its initial release, I found it generic; it did have violence and nudity, and was entertaining. However, I did not find it forgettable. Walking home with the first flecks of a winter snow weaving around me in the dark, I found myself thinking over it. I continually recalled images, sounds, and narrative moments that were vivid in my mind. Friday the 13th wormed into my brain, with its haunting and atmospheric style. After watching the original film several more times, I started in on the sequels, preparing myself for disappointment each time. -

A Study of Neurosis Through the Lens of Scopophilia ======

Pearse Kieran 10048609 MA in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy Pearse Kieran 10048609 MA in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy Thesis 27 June 2016 ======================== A study of neurosis through the lens of scopophilia ======================= (Word count 15,814) The thesis is submitted to the Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI) for the degree of MA in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy from Dublin Business School, School of Arts. Supervisor: Terry Ball (DBS) Page 1 of 50 Pearse Kieran 10048609 MA in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy CONTENTS: Title Page 1 Contents 2 Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 5 Introducing scopophilia 5 The Freudian & Lacanian positions 6 Chapter 2: THE RAT MAN & SCOPOPHILIA 11 The Rat Man’s Neurosis 11 The Rat Man’s Mother and her Oedipal Child 15 Discovering Lack and Restoring Completeness 20 The Rat Man’s Father and Castration 22 The Favourite Fantasy 26 The Primal Father 29 Chapter 3: FANTASY, PORNOGRAPHY & EROTIC ART 33 Chapter 4: CONCLUSIONS 42 References 48 Page 2 of 50 Pearse Kieran 10048609 MA in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy Acknowledgements I am grateful to everyone who helped me along the way of this formative and informative process, not least my partner Juliet Keating and my parents James and Tina Kieran. In particular, I would like to acknowledge the generous help and academic support of my thesis supervisor Terry Ball. Many others also helped along the way and they each have my gratitude, including: Rik Loose, Joanne Conway, Barry O’Donnell, and Grainne Donohue. Page 3 of 50 Pearse Kieran 10048609 MA in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy A study of neurosis through the lens of scopophilia By Pearse Kieran Abstract A study of neurosis through the lens of scopophilia – the desire to look - considers Freud’s case of the Rat Man. -

On Voyeurism: Being Seen on the Modern Stage

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2020 On Voyeurism: Being Seen on the Modern Stage Megan M. Mobley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons Recommended Citation Mobley, Megan M., "On Voyeurism: Being Seen on the Modern Stage" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2062. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/2062 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON VOYEURISM: BEING SEEN ON THE MODERN STAGE by MEGAN MOBLEY (Under the Direction of Dustin Anderson) ABSTRACT At the end of the nineteenth century, playwrights grew more interested in exploring the ramifications of the gaze, looking and being looked at. For existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre, the gaze causes a never-ending battle between our subjective selves, how we view ourselves, and our objective selves, or how others view us. The knowledge of the Other’s gaze allows us to self- reflect on our own existence. Sartre and Oscar Wilde each incorporate the gaze into their plays to explore the battle between our subjective and objective selves, gendered perception, differences in perception, and to undercut or demonstrates the dominant structures of seeing. By first exploring Sartre’s No Exit, I can observe how Sartre’s three main characters demonstrate Mulvey’s theories of the male gaze, a structure of looking which is influenced by the dominant social order. -

Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel Huber David Jaramillo Gil The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3862 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] QUEER BAROQUE: SARDUY, PERLONGHER, LEMEBEL by HUBER DAVID JARAMILLO GIL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 HUBER DAVID JARAMILLO GIL All Rights Reserved ii Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel by Huber David Jaramillo Gil This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Carlos Riobó Chair of Examining Committee Date Carlos Riobó Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Paul Julian Smith Magdalena Perkowska THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel by Huber David Jaramillo Gil Advisor: Carlos Riobó Abstract: This dissertation analyzes the ways in which queer and trans people have been understood through verbal and visual baroque forms of representation in the social and cultural imaginary of Latin America, despite the various structural forces that have attempted to make them invisible and exclude them from the national narrative. -

The Godfather, Part II

RANCIS FORD COPPOLA (Detroit, Michigan, 7 April 1939) has directed 30 films, among them Megalopolis 2005, John Grisham's The Rainmaker 1997, Bram Stoker's Dracula 1992, The Godfather: Part III 1990, Tucker: The Man and His Dream 1988, Gardens of Stone 1987, Peggy Sue Got Married 1986, The Cotton Club 1984, Rumble Fish 1983, The Outsiders 1983, One from the Heart 1982, Apocalypse Now 1979, The Conversation 1974, The Godfather 1972, The Rain People 1969, and Dementia 13 1963. He received Best Director Oscar nominations for Godfather Part III, Godfather Part II (won), Apocalypse Now, The Godfather; Best Picture nominations for Godfather Part III, Godfather Part II (won), Apocalypse Now, The Conversation, American Graffiti; Best Screenplay nominations for Apocalypse Now, Godfather Part II (won), The Conversation, The Godfather (won), and Patton November 30, 2004 (IX:14) (won). GORDON WILLIS ( 28 May 1931, Queens, NY) has shot 31 films. His colleagues call him the “Prince of Darkness” for his astonishing ability to get gorgeous scenes out of underexposed negatives. He did all three Godfather films, as well as many of Woody Allen’s films. Some of his films are The Devil's Own 1997, Malice 1993, Presumed Innocent 1990, Bright Lights, Big City 1988, The Purple Rose of Cairo 1985, Broadway Danny Rose 1984, Zelig 1983, A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy 1982, Pennies from Heaven 1981, Stardust Memories 1980, Manhattan 1979, Annie Hall 1977, The Drowning Pool 1975, The Parallax View 1974, Bad Company 1972, Klute 1971, Little Murders 1971, End of the Road I970 and others. He received Oscar nominations only for The Godfather: Part III and Zelig 1983. -

New Terrors, Emerging Trends and the Future of Japanese Horror

Chapter Six: New Terrors, Emerging Trends and the Future of Japanese Horror Repetition, Innovation, and ‘J-Horror’ Anthologies The following pages constitute not only this book’s final chapter, but its conclusion as well. I adopt this structural and rhetorical manoeuvre for two reasons. Firstly, the arguments advanced in this chapter provide a critical assessment of the state of the horror genre in Japanese cinema at the time of this writing. As a result, this chapter examines not only the rise of a self-reflexive tendency within recent works of Japanese horror film, but also explores how visual and narratological redundancy may compromise the effectiveness of future creations, transforming motifs into clichés and, quite possibly, reducing the tradition’s potential as an avenue for cultural critique and aesthetic intervention. As one might suspect, the promise of quick economic gain – motivated both by the genre’s popularity in Western markets, as well as by the cinematic tradition’s contribution to what James Udden calls a ‘pan-[east-]Asian’ film style (2005: para 5) – inform the fevered perpetuation of predictable shinrei mono eiga (‘ghost films’). Secondly, by examining the emergence of several visually inventive and intellectually sophisticated films by some of Japanese horror cinema’s most accomplished practitioners, this chapter proposes that the creative fires spawned by the explosion of Japanese horror in the 1990s are far from extinguished. As close readings 172 Nightmare Japan of works like Ochiai Masayuki’s Infection (Kansen, 2004), Tsuruta Norio’s Premonition (Yogen, 2004), Shimizu Takashi’s Marebito (2004), and Tsukamoto Shinya’s Vital (2004) variably reveal, the future of Japanese horror cinema may be very bright indeed.