Gwendolyn Mink Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

The Employment of Women in the Pineapple Canneries of Hawaii

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR BULLETIN OF THE WOMEN’S BUREAU, NO. 82 THE EMPLOYMENT OF WOMEN IN THE PINEAPPLE CANNERIES OF HAWAII Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis [Public—No. 259—66th Congress] [H. K. 13229] An Act To establish in the Department of Labor a bureau to be known as the Women’s Bureau Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That there shall be established in the Department of Labor a bureau to be known as the Women’s Bureau. Sec. 2. That the said bureau shall be in charge of a director, a woman, to be appointed by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, who shall receive an annual compensation of $5,000. It shall be the duty of said bureau to formulate standards and policies which shall promote the welfare of wage-earning women, improve their working conditions, increase their efficiency, and ad vance their opportunities for profitable employment. The said bureau shall have authority to investigate and report to the said de partment upon all matters pertaining to the welfare of women in industry. The director of said bureau may from time to time pub lish the results of these investigations in such a manner and to such extent as the Secretary of Labor may prescribe. Sec. 3. That there shall be in said bureau an assistant director, to be appointed by the Secretary of Labor, who shall receive an annual compensation of $3,500 and shall perform such duties as shall be prescribed by the director and approved by the Secretary of Labor. -

Women and the Presidency

Women and the Presidency By Cynthia Richie Terrell* I. Introduction As six women entered the field of Democratic presidential candidates in 2019, the political media rushed to declare 2020 a new “year of the woman.” In the Washington Post, one political commentator proclaimed that “2020 may be historic for women in more ways than one”1 given that four of these woman presidential candidates were already holding a U.S. Senate seat. A writer for Vox similarly hailed the “unprecedented range of solid women” seeking the nomination and urged Democrats to nominate one of them.2 Politico ran a piece definitively declaring that “2020 will be the year of the woman” and went on to suggest that the “Democratic primary landscape looks to be tilted to another woman presidential nominee.”3 The excited tone projected by the media carried an air of inevitability: after Hillary Clinton lost in 2016, despite receiving 2.8 million more popular votes than her opponent, ever more women were running for the presidency. There is a reason, however, why historical inevitably has not yet been realized. Although Americans have selected a president 58 times, a man has won every one of these contests. Before 2019, a major party’s presidential debates had never featured more than one woman. Progress toward gender balance in politics has moved at a glacial pace. In 1937, seventeen years after passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Gallup conducted a poll in which Americans were asked whether they would support a woman for president “if she were qualified in every other respect?”4 * Cynthia Richie Terrell is the founder and executive director of RepresentWomen, an organization dedicated to advancing women’s representation and leadership in the United States. -

Patsy Mink by D

LESSON 4 TEACHER’S GUIDE Patsy Mink by D. Jeanne Glaser Fountas-Pinnell Level W Narrative Nonfiction Selection Summary Pasty Mink experienced discrimination as a young woman, but she was determined to achieve her goals. She worked tirelessly to make sure that women in future generations had equal opportunities. Number of Words: 2,494 Characteristics of the Text Genre • Narrative nonfi ction, biography Text Structure • Third-person narrative in twelve short chapters • Chapter headings signal key periods in Patsy’s life and Title IX Content • Discrimination against women and immigrants • Passage of a bill in the United States Congress Themes and Ideas • Belief in oneself and determination can help overcome discrimination. • Everyone deserves equal opportunities. • People can initiate and make change. Language and • Conversational language Literary Features • Little fi gurative language—sprang into action Sentence Complexity • A mix of short and complex sentences • Complex sentences—phrases, clauses, compounds Vocabulary • New vocabulary words: instrumental, discrimination, emigrated • Words related to government and law: Title IX, debate, legislator, bill, repealed, lobby Words • Many multisyllable words: qualifying, intimidated, controversial Illustrations • Black-and-white/color photographs, some with captions Book and Print Features • Sixteen pages of text with chapter headings and photographs • Table of contents lists chapters headings • Text boxes highlight content • Timeline and diagram summarize content © 2006. Fountas, I.C. & Pinnell, G.S. Teaching for Comprehending and Fluency, Heinemann, Portsmouth, N.H. Copyright © by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner unless such copying is expressly permitted by federal copyright law. -

Congressional Record—Senate S6471

October 25, 2020 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S6471 Unfortunately, we are now at a point I yield back my time. ances, they did not envision a sham where this program has been tapped The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Sen- confirmation process for judicial nomi- out. Why? Because the $44 billion that ator from Delaware. nees. But as much as I hate to say it, was set aside in the Disaster Relief NOMINATION OF AMY CONEY BARRETT that is what this one has been, pure Fund is gone, leaving $25 billion to deal Mr. CARPER. Mr. President, I rise and simple. This entire process has be- with natural disasters, which is what this afternoon to share with you and come an exercise in raw political the Disaster Relief Fund is intended to our colleagues some of my thoughts power, not the deliberative, non- do. And they need that money. We concerning the nomination of Judge partisan process that our Founders en- shouldn’t use any more of that. So we Amy Coney Barrett to serve as an As- visioned. are back to square one. sociate Justice of the Supreme Court of Frankly, it has been a process that I People who have had unemployment these United States. could never have imagined 20 years ago insurance since the disaster began be- I believe it was Winston Churchill when I was first elected to serve with cause they might work in hospitality, who once said these words: ‘‘The fur- my colleagues here. Over those 20 entertainment, travel, some businesses ther back we look, the further forward years, I have risen on six previous oc- where they can’t go back—a lot of we see.’’ So let me begin today by look- casions to offer remarks regarding those folks now are seeing just a State ing back in time—way back in time. -

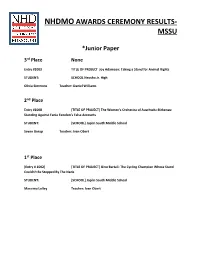

MSSU Results

NHDMO AWARDS CEREMONY RESULTS- MSSU *Junior Paper 3rd Place None Entry #1003 TITLE OF PROJECT Joy Adamson: Taking a Stand for Animal Rights STUDENT: SCHOOL Neosho Jr. High Olivia Simmons Teacher: Daniel Williams 2nd Place Entry #1008 [TITLE OF PROJECT] The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz-Birkenau: Standing Against Fania Fenelon’s False Accounts STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School Seven Borup Teacher: Ivan Obert 1st Place [Entry # 1002] [TITLE OF PROJECT] Gino Bartali: The Cycling Champion Whose Stand Couldn't Be Stopped By The Nazis STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School Massimo Lolley Teacher: Ivan Obert NHDMO AWARDS CEREMONY RESULTS- MSSU *Junior Individual Exhibit 3rd Place [Entry #] 1111 [TITLE OF PROJECT] Mary Wollstonecraft: The First Feminist to Fight For Women’s Education STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School [Student Name] Austyn Hughes Teacher: [Teacher Name] Ivan Obert 2nd Place [Entry #] 1123 [TITLE OF PROJECT] William Wilberforce: Taking a Stand Against British Slave Trade and Slavery STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School [Student Name] Jeana Compton Teacher: [Teacher Name] Ivan Obert 1st Place [Entry #] 1106 [TITLE OF PROJECT] Elizabeth Kenny: Taking A Stand On The Polio Epidemic STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School [Student Name] Ryan Zimmerman Teacher: [Teacher Name] Ivan Obert NHDMO AWARDS CEREMONY RESULTS- MSSU *Junior Group Exhibit 3rd Place [Entry #] 1215 [TITLE OF PROJECT] The White Rose Group; A Hazard to Hitler STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Nevada Middle School [Student Name 1] Ezinne Mba Teacher: [Teacher Name] Kim Greer [Student Name 2] Tylin Page Heathman [Student Name 3] [Student Name 4] 2nd Place [Entry #] 1212 [TITLE OF PROJECT] Riots for the Rights: East German Uprising of 1953 STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Mt. -

A Statistical Profile of Samoans in the United States. Part I: Demography; Part II: Social and Economic Characteristics; Appendix: Language Use Among Samoans

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 264 331 UD 024 599 AUTHOR Hayes, Ge'ffrey; Levin, Michael J. TITLE A Statistical Profile of Samoans in the United States. Part I: Demography; Part II: Social and Economic Characteristics; Appendix: Language Use among Samoans. Evidence from the 1980 Census. INSTITUTION Northwest Regional Educational Lab., Portland, Oreg. SPONS AGENCY Employment and Training Administration (DOL), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Dec 83 CONTRACT 99-3-r946-75-075-01 NOTE 117p.; A paper commissioned for a Study of Toverty, Unemployment and Training Needs of American Samoans. For related documents, see UD 024 599-603. PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Birth Rate; Census Figures; *Demography; *Educational Attainment; *Employment Level; Family Characteristics; Income; *Language Proficiency; Migr.tion Patterns; Population Growth; Poverty; *Samoan Americans; *Socioeconomic Status IDENTIFIERS California; Census 1980; Hawaii; *Samoans; Washington ABSTRACT This paper provides a broad overview of the demographic, social, and economic characteristics of Samoans in the United States, focusing particularly on the Samoan populations of Hawaii, California, and Washington, where 85% of Samoans reside. The data is derived from the "race" question on the 1980 Census and other local statistical materials. Demographically, the population is found to be highly urbanized, young (average age 19.5 years) and with a high fertility rate (averaging 4.3 children per adult woman). The total U.S. Samoan population projected for the year 2000 is most realistically estimated at 131,000. Among the three States, Hawaii's Samoans are youngest, with a higher dependency ratio and lower sex ratio than elsewhere in the United States. -

Congressional Record—Senate S3113

May 23, 2019 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S3113 student loans in exchange for a two- SUBMITTED RESOLUTIONS Whereas, in 1977, President Jimmy Carter year commitment at an NHSC-ap- nominated Patsy Takemoto Mink to serve as proved site, within two years of com- Assistant Secretary of State for Oceans and pleting their residency. Accepted par- SENATE RESOLUTION 219—HON- International Environmental and Scientific ORING THE LIFE AND LEGACY Affairs; ticipants may serve as primary care Whereas, in 2003, Patsy Takemoto Mink medical, dental, or mental/behavioral OF PATSY TAKEMOTO MINK, THE FIRST WOMAN OF COLOR TO was inducted into the National Women’s Hall health clinicians. of Fame; SERVE IN CONGRESS NHSCLRP provides critical relief to Whereas, on November 24, 2014, Patsy physicians who have completed pediat- Ms. HIRONO (for herself, Mr. SCHATZ, Takemoto Mink was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the high- rics or psychiatry residency training Ms. BALDWIN, Mr. BOOKER, Ms. CANT- WELL, Ms. CORTEZ MASTO, Ms. est civilian honor of the United States; programs; however, pediatric sub- Whereas November 3, 2019, marks the 55th DUCKWORTH, Mrs. FEINSTEIN, Mrs. specialists, such as child and adoles- anniversary of the election of Representative cent psychiatrists, are effectively GILLIBRAND, Ms. HARRIS, Ms. HASSAN, Mink to the House of Representatives; and barred from participating due to the Ms. KLOBUCHAR, Mrs. MURRAY, Ms. Whereas Patsy Takemoto Mink was a extra training these physicians are re- ROSEN, Mrs. SHAHEEN, Ms. SMITH, Ms. trailblazer who not only pioneered the way quired to take after completing their STABENOW, Mr. VAN HOLLEN, Ms. WAR- for women and minorities, but also embodied residency. -

The Impact of COVID-19 on Women in Hawaii and the Asia-Pacific

will have the greatest impact on single parents, most of whom are women. In Hawaii, 43 per cent of low- income households and 20 per cent of above low- income households are headed by a single parent. Even in households with two parents, mounting THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON childcare demands are likely to take a greater toll on WOMEN IN HAWAII AND women, who spend more time looking after children ASIA-PACIFIC than men. In the US, women spend on average four hours per day performing unpaid labor which includes BY JENNIFER HOWE childcare, shopping and housework, while men spend just two and a half hours. American women are also Jennifer Howe, MA (University of Durham, UK) is a eight times more likely to manage their children’s research intern at Pacific Forum. schedules than their male counterparts. In Asia and the Pacific, women undertake four times more unpaid Introduction care work than men. The unequal division of labor illustrated by these figures suggests that women, as Women’s voices are missing from Hawaii’s Covid-19 the primary caregivers, will more readily leave their economic response and recovery plan while the jobs if work arrangements cannot be adjusted to pandemic exacerbates existing inequalities that hinder accommodate childcare. Moreover, because women female empowerment. The coronavirus crisis is are typically paid less than men, there is more negatively affecting women’s economic participation incentive for the female partner to quit. Some women and empowerment, has led to greater rates of gender- have also reported feeling pressured to leave their jobs based violence, and has disrupted access to sexual and to care for children in order to be considered “good reproductive health. -

ED 078-451 AUTHOR TITLE DOCUMENT RESUME Weisman

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 078-451 AUTHOR Weisman, Martha TITLE Bow Women in Politics View the Role TheirSexPlays in the Impact of Their Speeches ,ontAudienees.. PUB DATE Mar 73 - - NOTE 15p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Eastern Communication Assn. (New York, March 1973) - _ - EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Communication (Thought Transfer; Females;_ Persuasive Discourse; *Political Attitudes;.Public Opinion; *Public Speaking; *Rhetorical Criticisn; *Sex Discrimination; Social Attitudes; *Speeches ABSTRACT While investigatingmaterialsfor a new course at City College of New York dealing with the rhetoric of women activists, women who were previously actively Involved in, the political scene* were asked to respoftd to the question, Does the fact that youare =awoolen affect the content, delivery, or reception of your ideas by theAudiences you haye addressed? If so, how? Women of diverse political and ethnic backgrounds replied.._Although the responses were highly subjective, many significant issues were recognized thatcallfor further investigation._While a number of women'denied that sex plays any role intheimpact of their ideas on audiences, others recognized the prejudices they face when delivering Speeches. At the same time* some women who identified the obstacles conceded that these prejudices can often be used to enhancetheir ethos. One of the-most-significant points emphasized was that we may have reached a new national. consciousness toward women politicians. _ FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLECOPY . HOW WOMEN IN POLITICS -

Women of Color Health Data Book

Ethnic and Racial Heritage women of color. Between 2000 and 2010, Hispanic women increased to 44 percent of all women of color, Of the nearly 309 million people living in the United while black non-Hispanic women decreased to States (according to the U.S. census conducted on 35 percent. April 1, 2010), more than half (157 million or 50.8 According to projections by the U.S. Census percent) were women. More than 56 million—more Bureau, the U.S. population will become more racially than a third (36.1 percent)—were women of color. and ethnically diverse by the middle of the 21st These 56.7 million women of color were distributed century. In 2043, the United States is projected to as follows: 44 percent Hispanic, 35 percent black become a majority-minority nation for the first time. (non-Hispanic), nearly 14 percent Asian (non- While the white non-Hispanic population will remain Hispanic), 2.0 percent American Indian and Alaska the largest single group, no group will make up a Native (non-Hispanic), and 0.4 percent Native Hawai- majority. The white non-Hispanic population is ian and Other Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic). An projected to peak in 2024, at nearly 200 million, and additional 5 percent of women of color identified then slowly decrease to 186 million in 2050, when they themselves as belonging to two or more races. In will account for 46.6 percent of the total population.3 raw numbers, there are nearly 25 million Hispanic Meanwhile, people of color are expected to total women, nearly 20 million black (non-Hispanic) women, more than 213 million in 2050, when they will more than 7 million Asian (non-Hispanic) women, account for 53.4 percent of the total population. -

Paths to Leadership of Native Hawaiian Women Administrators In

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Educational Administration: Theses, Dissertations, Educational Administration, Department of and Student Research Spring 5-2016 Paths to Leadership of Native Hawaiian Women Administrators in Hawaii's Higher Education System: A Qualitative Study Farrah-Marie Gomes University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cehsedaddiss Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, and the Higher Education Administration Commons Gomes, Farrah-Marie, "Paths to Leadership of Native Hawaiian Women Administrators in Hawaii's Higher Education System: A Qualitative Study" (2016). Educational Administration: Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research. 266. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cehsedaddiss/266 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Educational Administration, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Educational Administration: Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. PATHS TO LEADERSHIP OF NATIVE HAWAIIAN WOMEN ADMINISTRATORS IN HAWAII’S HIGHER EDUCATION SYSTEM: A QUALITATIVE STUDY by Farrah-Marie Kawailani Gomes A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: Educational Studies (Educational Leadership