A Tribute to Patsy Takemoto Mink

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

Women and the Presidency

Women and the Presidency By Cynthia Richie Terrell* I. Introduction As six women entered the field of Democratic presidential candidates in 2019, the political media rushed to declare 2020 a new “year of the woman.” In the Washington Post, one political commentator proclaimed that “2020 may be historic for women in more ways than one”1 given that four of these woman presidential candidates were already holding a U.S. Senate seat. A writer for Vox similarly hailed the “unprecedented range of solid women” seeking the nomination and urged Democrats to nominate one of them.2 Politico ran a piece definitively declaring that “2020 will be the year of the woman” and went on to suggest that the “Democratic primary landscape looks to be tilted to another woman presidential nominee.”3 The excited tone projected by the media carried an air of inevitability: after Hillary Clinton lost in 2016, despite receiving 2.8 million more popular votes than her opponent, ever more women were running for the presidency. There is a reason, however, why historical inevitably has not yet been realized. Although Americans have selected a president 58 times, a man has won every one of these contests. Before 2019, a major party’s presidential debates had never featured more than one woman. Progress toward gender balance in politics has moved at a glacial pace. In 1937, seventeen years after passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Gallup conducted a poll in which Americans were asked whether they would support a woman for president “if she were qualified in every other respect?”4 * Cynthia Richie Terrell is the founder and executive director of RepresentWomen, an organization dedicated to advancing women’s representation and leadership in the United States. -

Patsy Mink by D

LESSON 4 TEACHER’S GUIDE Patsy Mink by D. Jeanne Glaser Fountas-Pinnell Level W Narrative Nonfiction Selection Summary Pasty Mink experienced discrimination as a young woman, but she was determined to achieve her goals. She worked tirelessly to make sure that women in future generations had equal opportunities. Number of Words: 2,494 Characteristics of the Text Genre • Narrative nonfi ction, biography Text Structure • Third-person narrative in twelve short chapters • Chapter headings signal key periods in Patsy’s life and Title IX Content • Discrimination against women and immigrants • Passage of a bill in the United States Congress Themes and Ideas • Belief in oneself and determination can help overcome discrimination. • Everyone deserves equal opportunities. • People can initiate and make change. Language and • Conversational language Literary Features • Little fi gurative language—sprang into action Sentence Complexity • A mix of short and complex sentences • Complex sentences—phrases, clauses, compounds Vocabulary • New vocabulary words: instrumental, discrimination, emigrated • Words related to government and law: Title IX, debate, legislator, bill, repealed, lobby Words • Many multisyllable words: qualifying, intimidated, controversial Illustrations • Black-and-white/color photographs, some with captions Book and Print Features • Sixteen pages of text with chapter headings and photographs • Table of contents lists chapters headings • Text boxes highlight content • Timeline and diagram summarize content © 2006. Fountas, I.C. & Pinnell, G.S. Teaching for Comprehending and Fluency, Heinemann, Portsmouth, N.H. Copyright © by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner unless such copying is expressly permitted by federal copyright law. -

The American Legion 55Th National Convention: Official Program And

i 55 th NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE r r ~7T~rwmm T sr m TTi rri T r M in ml 1 15', mwryf XI T TT\W i TI Til J r, if A 1 m 3 tim i j g T Imp. Xi I xl m | T 1 n “Hi ^ S 1 33 1 H] I ink §j 1 1 ""fm. Jjp 1 — 1 ZD ^1 fll i [mgj*r- 11 >1 "PEPSI-COLA," "PEPSI," AND "TWIST-AWAY" ARE REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF PepsiCo, INC. Nothing downbeat here ... no blue notes. That’s because Pepsi- Cola delivers the happiest, rousingest taste in cola. Get the one with a lot to give. Pass out the grins with Pepsi . the happiest taste in cola. Ybu’ve got a lot to live. Pepsi’s got a lot to give. ; FOR^fSr OD ANDJK. OUNTRY THE AMERICAN LEGION 55 th National Convention WE ASSOCIATE OURSELVES TOGETHER FOR THE FOLLOWING PURPOSES To uphold and defend the Constitution of the United States of America; to maintain law and order; to foster and perpetuate a one hundred percent Americanism to preserve the memories and incidents of our associations in the Great Wars; to inculcate a sense of individual obligation to the community, state and nation; SONS OF THE AMERICAN LEGION to combat the autocracy of both the classes and the masses; to make right the 2nd National Convention master of might; to promote peace and good will on earth; to safeguard and transmit to posterity the principles of justice, freedom and democracy; to consecrate and sanctify our comradeship by our devotion to mutual helpfulness. -

DI SB441 F1 Ocrcombined.Pdf

March 5, 1980 The Honorable Dennis O’Connor The Senate The Tenth Legislature State of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Dear Dennis: I regret that I will not be in Hawaii on March 5, 1980, and therefore will not be able to attend the performance of ’’Big Boys Don’t Cry” and to view the display of pottery done by prisoners from the Kalihi-Palama Ceramics Class. Please convey my congratulations to the director of the play, Tremaine Tamayose, and to the teacher of the ceramics class, Mary Ellen Hankock, as well as the participants in the two programs. Aloha DANIEL K. INOUYE United States Senator DKI:jmpl I regret that I will not be able to attend the performance of "Big Boys Don't Cry" and to view the display of pottery done by prisoners from the Kalihi-Palam Ceramics Class. Please convey my congratulations to the director of the play Tremaine Tamayose, and to the teacher of the ceramics class* Mary Ellen Hankock, as well as the participants in the two programs. Aloha, DKI STATE SENATE PTj May 5, 1980 Mr. Seichi Hirai Clerk of the Senate The Tenth Legislature State of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Dear Shadow: This will acknowledge your recent communication transmitting a copy of Resolution No. 235, adopted by the State Senate during the regular session of 1980, which expresses the support of the Senate for a bikeway between Waimea and Kekaha, Kauai, Your thoughtfulness in sharing the abovementioned Resolution with me is most appreciated. Aloha, DANIEL K. INOUYE United States Senator DKI:jmpl RICHARD S. -

No. 24 Mormon Pacific Historical Society

Mormon Pacific Historical Society Proceedings 24th Annual Conference October 17-18th 2003 (Held at ‘Auwaiolimu Chapel in Honolulu) ‘Auwaiolimu Chapel (circa 1890’s) Built by Elder Matthew Noall Dedicated April 29, 1888 (attended by King Kalakaua and Queen Kapi’olani) 1 Mormon Pacific Historical Society 2003 Conference Proceedings October 17-18, 2003 Auwaiolimu (Honolulu) Chapel Significant LDS Historical Sites on Windward Oahu……………………………….1 Lukewarm in Paradise: A Mormon Poi Dog Political Journalist’s Journey ……..11 into Hawaii Politics Alf Pratte Musings of an Old “Pol” ………………………………………………………………32 Cecil Heftel World War Two in Hawaii: A watershed ……………………………………………36 Mark James It all Started with Basketball ………………………………………………………….60 Adney Komatsu Mormon Influences on the Waikiki entertainment Scene …………………………..62 Ishmael Stagner My Life in Music ……………………………………………………………………….72 James “Jimmy” Mo’ikeha King’s Falls (afternoon fieldtrip) ……………………………………………………….75 LDS Historical Sites (Windward Oahu) 2 Pounders Beach, Laie (narration by Wylie Swapp) Pier Pilings at Pounders Beach (Courtesy Mark James) Aloha …… there are so many notable historians in this group, but let me tell you a bit about this area that I know about, things that I’ve heard and read about. The pilings that are out there, that you have seen every time you have come here to this beach, are left over from the original pier that was built when the plantation was organized. They were out here in this remote area and they needed to get the sugar to market, and so that was built in order to get the sugar, and whatever else they were growing, to Honolulu to the markets. These (pilings) have been here ever since. -

Congressional Record—Senate S6471

October 25, 2020 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S6471 Unfortunately, we are now at a point I yield back my time. ances, they did not envision a sham where this program has been tapped The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Sen- confirmation process for judicial nomi- out. Why? Because the $44 billion that ator from Delaware. nees. But as much as I hate to say it, was set aside in the Disaster Relief NOMINATION OF AMY CONEY BARRETT that is what this one has been, pure Fund is gone, leaving $25 billion to deal Mr. CARPER. Mr. President, I rise and simple. This entire process has be- with natural disasters, which is what this afternoon to share with you and come an exercise in raw political the Disaster Relief Fund is intended to our colleagues some of my thoughts power, not the deliberative, non- do. And they need that money. We concerning the nomination of Judge partisan process that our Founders en- shouldn’t use any more of that. So we Amy Coney Barrett to serve as an As- visioned. are back to square one. sociate Justice of the Supreme Court of Frankly, it has been a process that I People who have had unemployment these United States. could never have imagined 20 years ago insurance since the disaster began be- I believe it was Winston Churchill when I was first elected to serve with cause they might work in hospitality, who once said these words: ‘‘The fur- my colleagues here. Over those 20 entertainment, travel, some businesses ther back we look, the further forward years, I have risen on six previous oc- where they can’t go back—a lot of we see.’’ So let me begin today by look- casions to offer remarks regarding those folks now are seeing just a State ing back in time—way back in time. -

MSSU Results

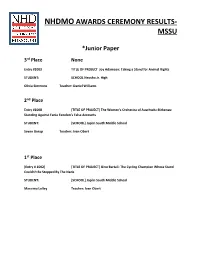

NHDMO AWARDS CEREMONY RESULTS- MSSU *Junior Paper 3rd Place None Entry #1003 TITLE OF PROJECT Joy Adamson: Taking a Stand for Animal Rights STUDENT: SCHOOL Neosho Jr. High Olivia Simmons Teacher: Daniel Williams 2nd Place Entry #1008 [TITLE OF PROJECT] The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz-Birkenau: Standing Against Fania Fenelon’s False Accounts STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School Seven Borup Teacher: Ivan Obert 1st Place [Entry # 1002] [TITLE OF PROJECT] Gino Bartali: The Cycling Champion Whose Stand Couldn't Be Stopped By The Nazis STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School Massimo Lolley Teacher: Ivan Obert NHDMO AWARDS CEREMONY RESULTS- MSSU *Junior Individual Exhibit 3rd Place [Entry #] 1111 [TITLE OF PROJECT] Mary Wollstonecraft: The First Feminist to Fight For Women’s Education STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School [Student Name] Austyn Hughes Teacher: [Teacher Name] Ivan Obert 2nd Place [Entry #] 1123 [TITLE OF PROJECT] William Wilberforce: Taking a Stand Against British Slave Trade and Slavery STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School [Student Name] Jeana Compton Teacher: [Teacher Name] Ivan Obert 1st Place [Entry #] 1106 [TITLE OF PROJECT] Elizabeth Kenny: Taking A Stand On The Polio Epidemic STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Joplin South Middle School [Student Name] Ryan Zimmerman Teacher: [Teacher Name] Ivan Obert NHDMO AWARDS CEREMONY RESULTS- MSSU *Junior Group Exhibit 3rd Place [Entry #] 1215 [TITLE OF PROJECT] The White Rose Group; A Hazard to Hitler STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Nevada Middle School [Student Name 1] Ezinne Mba Teacher: [Teacher Name] Kim Greer [Student Name 2] Tylin Page Heathman [Student Name 3] [Student Name 4] 2nd Place [Entry #] 1212 [TITLE OF PROJECT] Riots for the Rights: East German Uprising of 1953 STUDENT: [SCHOOL] Mt. -

Gwendolyn Mink Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript

Gwendolyn Mink Daughter of the Honorable Patsy Takemoto Mink of Hawaii Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript March 14, 2016 Office of the Historian U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. “Well, I think that every little thing—or maybe not so little thing—that the women in Congress dared to speak about, whether it was, you know, not having gym access in the 1960s, or insisting that Anita Hill be heard in 1991, to insisting that certain kinds of women’s issues get a full hearing—I think all of those things have been part of the story of women in Congress, and part of my mother’s story of being a woman in Congress. I think that what she took from her service was a constant reminder to herself of how important it is that women serve in Congress. Because one woman can’t accomplish what 218 women could, right? And so her goal was parity for women, for the whole full range of women’s voices. I think she hoped that the legacy of being the first woman of color, and being a woman who was willing to talk about women, you know, that that would be part of what she would leave to the future.” Gwendolyn Mink March 14, 2016 Table of Contents Interview Abstract i Interviewee Biography i Editing Practices ii Citation Information ii Interviewer Biography iii Interview 1 Notes 40 Abstract In this interview, Gwendolyn Mink reflects on the life and career of her mother, the late Congresswoman Patsy Takemoto Mink of Hawaii, the first woman of color and the first Asian- American woman to serve in the U.S. -

Congressional Record—Senate S3113

May 23, 2019 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S3113 student loans in exchange for a two- SUBMITTED RESOLUTIONS Whereas, in 1977, President Jimmy Carter year commitment at an NHSC-ap- nominated Patsy Takemoto Mink to serve as proved site, within two years of com- Assistant Secretary of State for Oceans and pleting their residency. Accepted par- SENATE RESOLUTION 219—HON- International Environmental and Scientific ORING THE LIFE AND LEGACY Affairs; ticipants may serve as primary care Whereas, in 2003, Patsy Takemoto Mink medical, dental, or mental/behavioral OF PATSY TAKEMOTO MINK, THE FIRST WOMAN OF COLOR TO was inducted into the National Women’s Hall health clinicians. of Fame; SERVE IN CONGRESS NHSCLRP provides critical relief to Whereas, on November 24, 2014, Patsy physicians who have completed pediat- Ms. HIRONO (for herself, Mr. SCHATZ, Takemoto Mink was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the high- rics or psychiatry residency training Ms. BALDWIN, Mr. BOOKER, Ms. CANT- WELL, Ms. CORTEZ MASTO, Ms. est civilian honor of the United States; programs; however, pediatric sub- Whereas November 3, 2019, marks the 55th DUCKWORTH, Mrs. FEINSTEIN, Mrs. specialists, such as child and adoles- anniversary of the election of Representative cent psychiatrists, are effectively GILLIBRAND, Ms. HARRIS, Ms. HASSAN, Mink to the House of Representatives; and barred from participating due to the Ms. KLOBUCHAR, Mrs. MURRAY, Ms. Whereas Patsy Takemoto Mink was a extra training these physicians are re- ROSEN, Mrs. SHAHEEN, Ms. SMITH, Ms. trailblazer who not only pioneered the way quired to take after completing their STABENOW, Mr. VAN HOLLEN, Ms. WAR- for women and minorities, but also embodied residency. -

![Presidential Files; Folder: 9/17/80 [1]; Container 176](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7735/presidential-files-folder-9-17-80-1-container-176-1407735.webp)

Presidential Files; Folder: 9/17/80 [1]; Container 176

9/17/80 [1] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 9/17/80 [1]; Container 176 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf WITHDRAWAL: SH,EET (llRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES) ,, '-' ., ,. ' �0 FORM OF ' ' " DA1E RESTRICTION CORR.ESPOND�NTS OR TITLE 0 DOCUMENT o'li, 0. � .. ,. ·, c;;' " o· ' ' 0 ��· memo From Brown to The President. ( 2 0 pp.) re: Weekly '9/12}8'0 A Activities of Sec. of Defense/enclosed in Hut- ' cheson. to Mondale 9/17/80 ,. ' " 0 ' " 0 0 " ' ., !; ' " " 0 :FILE LOCATION Carter Presidential Papers- Staff Offices, Office of �he Staff Sec.- · Pres.'· Handwriting File 9/17/80 [1] BOX 205 RESTRICTION CODES ' �' ' (A) Closed by Executive Order 12356'govern.ing access to national security information. (B) Closed by statute or by the agency which originated the document. (C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gift. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION. ' .. Electrostatic Copy Msde PuQ'POHS for Presewatlon MEMORANDUM #5134 THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON ACTION MEMORANDUM FOR: THE PRESIDENT #/.--:--. ·,\·r ) \ ... , FROM: ZBIGNIEW BRZEZINSKI , 1, J \. ; \ \ SUBJECT: Intelligence Oversight We may have the opportunity to obtain acceptable intelligence oversight based on an arrangement recently worked out between the Senate and House Intelligence Committees. We need your guidance on how to proceed. Comprehensive intelligence oversight by Congress was a fundamental feature of the intelligence charter that was waylaid this year because of conflicting legislative priorities. Even though the charter is no longer under consideration, intelligence oversight language has continued in a variety of legislative vehicles. -

ED 078-451 AUTHOR TITLE DOCUMENT RESUME Weisman

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 078-451 AUTHOR Weisman, Martha TITLE Bow Women in Politics View the Role TheirSexPlays in the Impact of Their Speeches ,ontAudienees.. PUB DATE Mar 73 - - NOTE 15p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Eastern Communication Assn. (New York, March 1973) - _ - EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Communication (Thought Transfer; Females;_ Persuasive Discourse; *Political Attitudes;.Public Opinion; *Public Speaking; *Rhetorical Criticisn; *Sex Discrimination; Social Attitudes; *Speeches ABSTRACT While investigatingmaterialsfor a new course at City College of New York dealing with the rhetoric of women activists, women who were previously actively Involved in, the political scene* were asked to respoftd to the question, Does the fact that youare =awoolen affect the content, delivery, or reception of your ideas by theAudiences you haye addressed? If so, how? Women of diverse political and ethnic backgrounds replied.._Although the responses were highly subjective, many significant issues were recognized thatcallfor further investigation._While a number of women'denied that sex plays any role intheimpact of their ideas on audiences, others recognized the prejudices they face when delivering Speeches. At the same time* some women who identified the obstacles conceded that these prejudices can often be used to enhancetheir ethos. One of the-most-significant points emphasized was that we may have reached a new national. consciousness toward women politicians. _ FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLECOPY . HOW WOMEN IN POLITICS