Being in the Language of Poetry, Being in the Language of Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 24, No. 8, Oct, 1979

ON THE INSIDE | If! Iranian woman speaks p. 2 jjj 111 International Marxist-Humanist III Youth Committee p. 7 !j! jjj Editorial: Best UAW contract — for GM p. 5 jjj to WtllKEK^ JftVfcHAL tu»*>"*»*> fl^nu «.»— Worker-author *~th;- f''"^ ^U£**>i* » * + **• **^r- •-lr^ji-K- "\*»«\.#.. naib lies *-f^A„. wws y^.O«"»U tu- »^Si. about book by Charles Denby, Editor Author of Indignant Heart: A Black Worker's Journal The following letter is my response to a slander ous review of my book, Indignant Heart: A Black Work er's Journal, by Manning Marable, an associate pro fessor in the Department of History and Ethnic Studies at the University of San Francisco. Printed in the August 16, 1979 issue of WIN magazine, the review not only has many errors of fact, but is such a serious attack against me that I feel strongly about the need for this immediate reply. * * * 97 Printed in 100 Percent Associate Professor Manning Marable's review of VOL 24—NO. 8 *• ' Union Shop OCTOBER, 1979 my book, Indignant Heart: A Black Worker's Journal, sharply brought to mind what Marx must have meant when he said, "The educators must be educated." Two Worlds For example, Marable knows well that the workers' paper I edit is News & Letters, not News & Notes. This is deliberate falsification. In my book I refer to News & Letters many times. It is not only a workers' news paper, it is the official monthly publication of News and ON THE THRESHOLD OF THE 1980s Letters Committees, the organization of Marxist-Human The following excerpts are taken from the Perspec had been creaking because of its imperialist war in ists in the U.S. -

1985 Commencement Program, University Archives, University Of

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA Two Hundred Twenty-Ninth Commencement for the Conferring of Degrees PHILADELPHIA CIVIC CENTER CONVENTION HALL Monday, May 20, 1985 Guests will find this diagram helpful in locating the Contents on the opposite page under Degrees in approximate seating of the degree candidates. The Course. Reference to the paragraph on page seven seating roughly corresponds to the order by school describing the colors of the candidates' hoods ac- in which the candidates for degrees are presented, cording to their fields of study may further assist beginning at top left with the College of Arts and guests in placing the locations of the various Sciences. The actual sequence is shown in the schools. Contents Page Seating Diagram of the Graduating Students 2 The Commencement Ceremony 4 Commencement Notes 6 Degrees in Course 8 • The College of Arts and Sciences 8 The College of General Studies 16 The School of Engineering and Applied Science 17 The Wharton School 25 The Wharton Evening School 29 The Wharton Graduate Division 31 The School of Nursing 35 The School of Medicine 38 v The Law School 39 3 The Graduate School of Fine Arts 41 ,/ The School of Dental Medicine 44 The School of Veterinary Medicine 45 • The Graduate School of Education 46 The School of Social Work 48 The Annenberg School of Communications 49 3The Graduate Faculties 49 Certificates 55 General Honors Program 55 Dental Hygiene 55 Advanced Dental Education 55 Social Work 56 Education 56 Fine Arts 56 Commissions 57 Army 57 Navy 57 Principal Undergraduate Academic Honor Societies 58 Faculty Honors 60 Prizes and Awards 64 Class of 1935 70 Events Following Commencement 71 The Commencement Marshals 72 Academic Honors Insert The Commencement Ceremony MUSIC Valley Forge Military Academy and Junior College Regimental Band DALE G. -

1999 Newsletter

WAYNE STATE eu er UNJVERSIT)' b r a r y Fall I Winter 1999-2000 Jerome P. Cavanagh Jerome P. Cavanagh was one of the most dynamic and influential mayors in the history of Detroit (1962-1970). Mayor during one of the city's--and America's--most turbulent decades, his career was meteoric, complete with storybook triumphs and great adversi- ties. After winning his first-ever political campaign in 1961 , the 33-year-old mayor soon became a national spokesman for cities, Mayor Jerome P Cavanagh, c. 1966. a shaper of federal urban policies, an advisor to U.S . presidents and one of "urban America's most articulate spokesman." He The Jerome P. Cavanagh also faced what was perhaps Detroit's worst Fellowship for Research in hour when a great civil disorder erupted on city streets in July 1967. Subsequently, until Urban History he left office in 1970, Cavanagh endured great criticism and personal adversity. The Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs The Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection was has established The Jerome P. Cavanagh donated to the Archives of Labor and Urban Fellowship for research in urban history. This award will offer short-term fellowships for Affairs after his death on November 27, research in residence at the Walter P. Reuther It 1979. is a superb resource regarding the Library. history of Detroit during the 1960s. This fellowship will allow researchers to To mark the 20th anniversary of utilize the Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection and Cavanagh's death and the opening of his col- other related collections held by the Reuther lection for research, the Walter P. -

Research Paper

Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Research Paper Detroit: What Lessons for Victoria from a ‘Post-Industrial’ City? No. 2, December 2015 Tom Barnes Research Fellow, Parliamentary Library & Information Service Institute for Religion, Politics and Society Australian Catholic University Level 6, 215 Spring St, Melbourne VIC 3000 [email protected] ISSN 2204-4752 (Print) 2204-4760 (Online) © 2015 Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Parliament of Victoria Research Papers produced by the Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria are released under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs licence. By using this Creative Commons licence, you are free to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: . Attribution - You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non-Commercial - You may not use this work for commercial purposes without our permission. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without our permission. The Creative Commons licence only applies to publications produced by the Library, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria. All other material produced by the Parliament -

Passenger Car Parts Catalog Information

GENERAL Page INF-2 1964 PASSENGER CAR PARTS CATALOG INFORMATION INDEX TO INFORMATION PAGES PAGE NO. ABBREVIATIONS ............................... INF-19 - ALPHABETICAL INDEX ........................... INF-20 COLOR CODED OR MIXED PART NUMBERS ................. INF-23 COLORED PAGE IDENTIFICATION. ..................... INF-21 ENGINE IDENTIFICATION NUMBERS .................... INF-18 HOW TO LOCATE PARTS. .......................... INF-22 ILLUSTRATIONS ............................... INF-20 INTERFILING REVISION PAGES ....................... LNF - 22 MODEL CODES. ............................... INF- 3 MODEL SPECIFICATIONS ........................... INF- 6 VALIANT PLYMOUTH DART DODGE 880 CHRYSLER IMPERIAL NUMERICAL INDEX ...................... INF-20 ORDERING INFORMATION .......................... INF-23 PAGE NUMBERING. ............................. INF-21 PAINT AND TRIM SPECIFICATIONS. .................... INF- 8 VALIANT PLYMOUTH DART DODGE 880 CHRYSLER IMPERIAL PARTS CATALOG REVISION SERVICE. ................... INF-22 PARTS PACKAGES ............................ INF-21 PART. TYPE CODE SYSTEM ......................... INF-21 BERIAL NUMBERS .............................. INF- 4 SPECIFYING INFORMATION ......................... INF-22 STANDARD PARTS ........................... INF-21 SYMBOLS USED IN THIS CATALOG ..................... INF-18 September 6, 1083. Page INF-a ~bnedhu~~. GENERAL INFORMATION 196-4-P-ASSENGER CAR PARTS CATALOG Page INF-s GENERAL INFORMATION - .. .. This publication contains parts idormation for 1864 Plymouth, Valiant, -

Fight for a Workers' Program to Save Jobs, Homes!

MUNDO OBRERO • La burbuja expansionista de la OTAN 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org OCT. 9, 2008 VOL. 50, NO. 40 50¢ Handout to the rich ignites people’s anger Fight for a workers’ program to save jobs, homes! By Fred Goldstein from below has for the moment overcome are only against government intervention Paulson, Bernanke and company. that might put restraints on the unbridled WHERE’S Sept. 30—The political and financial profit-seeking activity of big business. establishment of U.S. capitalism has been Capitalism’s faithful parties It is hard to tell whether these right- OUR BAILOUT? stunned by the failure of its initial attempt gripped by fear wingers voted “no” out of concerns of to get Congress to pass a $700-billion The growing economic crisis produced ideology or pragmatic protection of their handout to the banks. a political crisis in the two faithful par- seats in the House or both. Whatever their Protests Against a background of bank failures ties of capitalism. On the one hand, the motives, their political rhetoric against across in the U.S. and Europe and appeals from Democratic Party leadership was unable “big government,” which used to be the the White House and the Treasury sec- to force some 40 percent of its members applauded on Wall Street, has suddenly country retary, the House of Representatives on to sign on to this gigantic giveaway to been made obsolete by the present crisis. Sept. 29 defeated the bailout bill, 228 to billionaires this time around, especially The once high-and-mighty tycoons of 205. -

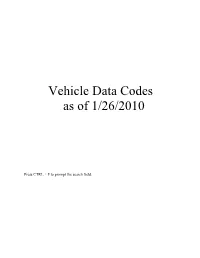

H:\My Documents\Article.Wpd

Vehicle Data Codes as of 1/26/2010 Press CTRL + F to prompt the search field. VEHICLE DATA CODES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1--LICENSE PLATE TYPE (LIT) FIELD CODES 1.1 LIT FIELD CODES FOR REGULAR PASSENGER AUTOMOBILE PLATES 1.2 LIT FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 1.3 LIT FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES AND SNOWMOBILES 1.4 SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 1.5 LIT FIELD CODES FOR SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 2--VEHICLE MAKE (VMA) AND BRAND NAME (BRA) FIELD CODES 2.1 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES 2.2 VMA, BRA, AND VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, LIGHT- DUTY TRUCKS, AND PARTS 2.3 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT AND CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.4 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT AND FARM EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.5 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR MOTORCYCLES AND MOTORCYCLE PARTS 2.6 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR SNOWMOBILES AND SNOWMOBILE PARTS 2.7 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRAILERS AND TRAILER PARTS 2.8 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRUCKS AND TRUCK PARTS 2.9 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES ALPHABETICALLY BY CODE 3--VEHICLE MODEL (VMO) FIELD CODES 3.1 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, AND LIGHT-DUTY TRUCKS 3.2 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ASSEMBLED VEHICLES 3.3 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 3.4 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES 3.5 VMO FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT 3.6 VMO FIELD CODES FOR DUNE BUGGIES 3.7 VMO FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT 3.8 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GO-CARTS 3.9 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GOLF CARTS 3.10 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED RIDE-ON TOYS 3.11 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED WHEELCHAIRS 3.12 -

Recent Books

Michigan Law Review Volume 95 Issue 7 1997 Recent Books Michigan Law Review Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation Michigan Law Review, Recent Books, 95 MICH. L. REV. 2343 (1997). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol95/iss7/6 This Regular Feature is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECENT BOOKS BOOKS RECEIVED ADMINISTRATIVE LAW Robert A. Hillman. Boston: Kluwer Aca AN INTRODUCllON TO ADMINISTRATIVE demic Publishers. 1997. Pp. xiv, 279. $115. LAw, 3RD ED. By Peter Cane. New York: Clarendon Press/Oxford University Press. ENTERTAINMENT 1996. Pp. xi, 401. $69. THE YE ARBO OK OF MEDIA AND ENTERTAINMENT LAw 1996. Edited by Eric ATTORNEYS M. Barendt. New York: Clarendon Press/ LAWYERLAND. By Lawrence Joseph. New Oxford University Press. 1996. Pp. xii, 592. York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 1997. Pp. $245. 225. $22. EUROPEAN COMMUNITY CHILD CUSTODY EC COMPETITION LAW IN THE TRANS FATHERS' RIGHTS: HARD-HITTING & PORT SECTOR. By Luis Ortiz Blanco & Ben FAIR ADV ICE FOR EVERY FATHER Van Houtte. New York: Clarendon Press/ INVOLVED IN A CuSTODY DISPUTE. By Jef Oxford University Press. 1996. Pp. xlvii, fery M. Leving with Kenneth A. Dachman, 288. $145. Ph.D. New York: Basic Books. 1997. Pp. xvii, 222. -

I Wildcat of the Streets: Race, Class and the Punitive Turn

Wildcat of the Streets: Race, Class and the Punitive Turn in 1970s Detroit by Michael Stauch, Jr. Department of History Duke University Date: Approved: ___________________________ Robert R. Korstad, Supervisor ___________________________ Adriane Lentz-Smith ___________________________ Dirk Bönker ___________________________ Thavolia Glymph ___________________________ Matthew Lassiter Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 i v ABSTRACT Wildcat of the Streets: Race, Class and the Punitive Turn in 1970s Detroit by Michael Stauch, Jr. Department of History Duke University Date: Approved: ___________________________ Robert R. Korstad, Supervisor ___________________________ Adriane Lentz-Smith ___________________________ Dirk Bönker ___________________________ Thavolia Glymph ___________________________ Matthew Lassiter An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 i v Copyright by Michael Stauch, Jr. 2015 Abstract This dissertation is a history of the city of Detroit in the 1970s. Using archives official and unofficial - oral histories and archived document collections, self-published memoirs and legal documents, personal papers and the newspapers of the radical press – it portrays a city in flux. It was in the 1970s that the urban crisis in the cities of the United States crested. Detroit, as had been the case throughout the twentieth century, was at the forefront of these changes. This dissertation demonstrates the local social, political, economic and legislative circumstances that contributed to the dramatic increase in prison populations since the 1970s. In the streets, unemployed African American youth organized themselves to counteract the contracted social distribution allocated to them under rapidly changing economic circumstances. -

Chrysler Shipments of World War Two Products

Chrysler Shipments of War Products (*) In Thousans of Items (**) In Thousands of Dollars Product Year Jan. Feb. Mar. April May June July August Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec. YearTotal Accum.Total Airtemp 1942 253 135 49 42 75 62 74 118 95 59 40 90 1,092 AirConditioningandrefrigeration 1943 60 95 285 186 256 327 336 150 96 250 152 126 2,319 units 1944 190 140 80 112 91 229 139 246 199 171 311 122 2,030 1945 327 392 326 639 1.155 1,281 921 672 645 858 900 813 8.929 14,370 Bomb Chute Assembly - A20 1944 58 107 91 44 ________ 300 300 1940 _________ 717 2,304 985 4,006 1941 __________ 835 1,718 2,553 Field Kitchen Cabinets 1942 1 ___ 4 498 3,681 5,032 5,202 4,240 3,841 3,520 26,019 1943 2,720 2,720 2,720 2,720 2,214 _______ 13,094 1944 __________ 816 3,720 4,536 1945 4,965 4,692 2,306 21 ________ 11,984 62,192 Field Kitch Conv. - Gen. Units 1944 __ 23,616 36,000 50,160 48,720 34,800 13,920 20,880 5,022 __ 233,118 233,118 1941 582 1,412 385 427 334 1,022 986 804 906 1,231 947 854 9,890 Furnaces-Gas,OilFired 1942 977 344 270 739 69 489 48 39 95 7 4 9 3,090 1943 _ 2 6 1 _ 93 13 _ 2 24 35 18 194 1944 15 37 24 88 74 12 24 136 155 302 100 94 1,061 1945 55 81 57 78 49 56 127 44 177 235 502 1,504 2,965 17,200 1940 ___________ 5,073 5,073 1941 480 _______ 2 ___ 482 Heaters,Misc.-Water,domestic 1942 293 504 489 989 288 622 16 4 253 31 2 504 3,994 and export 1943 1 _ 8 2 191 _ 545 246 22 246 251 829 2.341 1944 997 1,018 75 150 118 197 782 907 1,628 1,269 384 394 7,919 1945 477 232 810 782 1,233 1,056 1,237 1,472 485 641 383 971 9,779 29,589 Nose Cap Assembly - A20 1944 _ 2 51 100 169 217 221 147 ____ 907 907 1943 __________ 16,284 17,065 33,349 OerlikonMagazineLeverAssy. -

The Game Changed

The Game Changed Lawrence Joseph The Game Changed essays and other prose THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS Ann Arbor Copyright © 2011 by Lawrence Joseph All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2014 2013 2012 2011 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Joseph, Lawrence, 1948– The game changed : essays and other prose / Lawrence Joseph. p. cm. — (Poets on poetry series) ISBN 978-0-472-07161-6 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-472- 05161-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-472-02774-3 (ebk.) 1. Joseph, Lawrence, 1948– Knowledge—Poetry. 2. Poetry. I. Title. PS3560.O775G36 2011 814'.54—dc22 2011014828 For Laurence Goldstein Acknowledgments “The Poet and the Lawyer: The Example of Wallace Stevens” was presented as a talk at the Eleventh Annual Wallace Stevens Birthday Bash, sponsored by The Hartford Friends of Wallace Stevens, at the Hartford Public Library, on October 7, 2006. “Michael Schmidt’s Lives of the Poets” originally appeared in The Nation, December 13, 1999, under the title “New Poetics (Sans Aristotle).” “A Note on ‘That’s All’” originally appeared, in slightly different form, in Ecstatic Occasions, Expedient Forms, edited by David Lehman (Macmillan, 1987). -

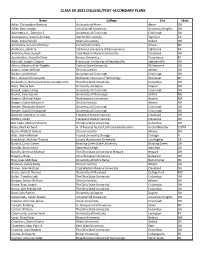

Class of 2021 College & Post Secondary Plans-1

CLASS OF 2021 COLLEGE/POST-SECONDARY PLANS Name College City State Adler, Christopher Bennett University of Akron Akron OH Adler, Ryan Joseph John Carroll University University Heights OH Adornetto Jr., Dominic S. University of Cincinnati Cincinnati OH Alexopoulos, Vassilis Andreas Stanford University Stanford CA Allen, Drew Patrick Miami University Oxford OH Amendola, Connor Anthony Cornell University Ithaca NY Anderson, DeVar G California University of Pennsylvania California PA Anthony, Ryan Joseph Case Western Reserve University Cleveland OH Apostolakis, Aristotle Peter Brown University Providence RI Ashcraft, Joseph Clayton Franciscan University of Steubenville Steubenville OH Atkins, Masario Allen-Rogelio Central State University Wilberforce OH Austin, Aidan William Ohio University Athens OH Barker, Ian Michael Universtiy of Cincinnati Cincinnati OH Bart, Jackson Christopher Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester NY Barzacchini, Nicholas Anthony Joseph John The Ohio State University Columbus OH Basic, Nikola Ivan University of Dayton Dayton OH Baszuk, Logan James University of Cincinnati Cincinnati OH Becker, John Gerald University of Mississippi Oxford MS Bednar, Michael Adam Northeastern University Boston MA Beegan, Caden Benjamin Ohio University Athens OH Bender, Alexander Daniel University of Cincinnati Cincinnati OH Bender, David Christopher University of Cincinnati Cincinnati OH Bennett, DeAndre Cristian Cleveland State University Cleveland OH Betters, Owen Cleveland State University Cleveland OH Biernacki, Michael Vincent