Appendix 1: Conversion Tables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atergatis Roseus Ordine Decapoda (Rüppell, 1830) Famiglia Xanthidae

Identificazione e distribuzione nei mari italiani di specie non indigene Classe Malacostraca Atergatis roseus Ordine Decapoda (Rüppell, 1830) Famiglia Xanthidae SINONIMI RILEVANTI Nessuno. DESCRIZIONE COROLOGIA / AFFINITA’ Tropicale e sub-tropicale settentrionale e Carapace allungato trasversalmente, fortemente meridionale. sub-ovale, convesso, minutamente punteggiato; regioni non definite. Fronte stretta. Antennule ripiegate trasversalmente, setto inter-antennulare DISTRIBUZIONE ATTUALE largo. Margine dorso-orbitale con tre suture, Dal Mar Rosso alle Fiji. peduncoli oculari corti e spessi. Margine antero- laterale molto arcuato, smussato e carenato. Lato PRIMA SEGNALAZIONE IN MEDITERRANEO inferiore del carapace concavo. Chelipedi sub- 1961, Israele (Lewinsohn & Holthuis, 1964). eguali, margine superiore della chela dotato di una cresta smussata. Cresta dorsale anche sul mero degli altri pereiopodi. PRIMA SEGNALAZIONE IN ITALIA - COLORAZIONE Carapace rosso-brunastro scuro, estremità delle dita delle chele nera. Nei giovani, il carapace è ORIGINE arancio-rosso orlato di bianco. Indo-Pacifico FORMULA MERISTICA VIE DI DISPERSIONE PRIMARIE Probabile migrazione lessepsiana attraverso il - Canale di Suez. TAGLIA MASSIMA VIE DI DISPERSIONE SECONDARIE Lunghezza del carapace fino a 60 mm. - STADI LARVALI STATO DELL ’INVASIONE Non nativo - Identificazione e distribuzione nei mari italiani di specie non indigene SPECIE SIMILI MOTIVI DEL SUCCESSO Xanthidae autoctoni Sconosciuti CARATTERI DISTINTIVI SPECIE IN COMPETIZIONE Carapace regolarmente ovale, -

First Mediterranean Record of Actaea Savignii (H. Milne Edwards, 1834) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Xanthidae), an Additional Erythraean Alien Crab

BioInvasions Records (2013) Volume 2, Issue 2: 145–148 Open Access doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3391/bir.2013.2.2.09 © 2013 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2013 REABIC Rapid Communication First Mediterranean record of Actaea savignii (H. Milne Edwards, 1834) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Xanthidae), an additional Erythraean alien crab Selahattin Ünsal Karhan1*, Mehmet Baki Yokeş2, Paul F. Clark3 and Bella S. Galil4 1 Division of Hydrobiology, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Istanbul University, 34134 Vezneciler, Istanbul, Turkey 2 Department of Molecular Biology & Genetics, Faculty of Arts & Sciences, Haliç University, 34381 Sisli, Istanbul, Turkey 3 Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, England 4 National Institute of Oceanography, Israel Oceanographic & Limnological Research, POB 8030, Haifa 31080, Israel E-mail: [email protected] (SÜK), [email protected] (MBY), [email protected] (PFC), [email protected] (BSG) *Corresponding author Received: 19 January 2013 / Accepted: 8 March 2013 / Published online: 16 March 2013 Handling editor: Amy Fowler Abstract To date, the only alien xanthid crab recorded from the Mediterranean is Atergatis roseus (Rüppell, 1830). This species was first collected off Israel in 1961 and is now common along the Levantine coast. Recently a second alien xanthid species, Actaea savignii (H. Milne Edwards, 1834), was found off Israel and Turkey. A single adult specimen was collected in Haifa Bay in 2010, and two specimens were captured off Mersin, Turkey in 2011. Repeatedly reported from the Suez Canal since 1924, the record of the Levantine populations of A. savignii is a testament to the ongoing Erythraean invasion of the Mediterranean Sea. -

New Records of Xanthid Crabs Atergatis Roseus (Rüppell, 1830) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) from Iraqi Coast, South of Basrah City, Iraq

Arthropods, 2017, 6(2): 54-58 Article New records of xanthid crabs Atergatis roseus (Rüppell, 1830) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) from Iraqi coast, south of Basrah city, Iraq Khaled Khassaf Al-Khafaji, Aqeel Abdulsahib Al-Waeli, Tariq H. Al-Maliky Marine Biology Dep. Marine Science Centre, University of Basrah, Iraq E-mail: [email protected] Received 5 March 2017; Accepted 5 April 2017; Published online 1 June 2017 Abstracts Specimens of the The Brachyuran crab Atergatis roseus (Rüppell, 1830), were collected for first times from Iraqi coast, south Al-Faw, Basrah city, Iraq, in coast of northwest of Arabian Gulf. Morphological features and distribution pattern of this species are highlighted and a figure is provided. The material was mostly collected from the shallow subtidal and intertidal areas using trawl net and hand. Keywords xanthid crab; Atergatis roseus; Brachyura; Iraqi coast. Arthropods ISSN 22244255 URL: http://www.iaees.org/publications/journals/arthropods/onlineversion.asp RSS: http://www.iaees.org/publications/journals/arthropods/rss.xml Email: [email protected] EditorinChief: WenJun Zhang Publisher: International Academy of Ecology and Environmental Sciences 1 Introduction The intertidal brachyuran fauna of Iraq is not well known, although that of the surrounding areas of the Arabian Gulf (=Persian Gulf) has generally been better studied (Jones, 1986; Al-Ghais and Cooper, 1996; Apel and Türkay, 1999; Apel, 2001; Naderloo and Schubart, 2009; Naderloo and Türkay, 2009). In comparison to other crustacean groups, brachyuran crabs have been well studied in the Arabian Gulf (=Persian Gulf) (Stephensen, 1946; Apel, 2001; Titgen, 1982; Naderloo and Sari, 2007; Naderloo and Türkay, 2012). -

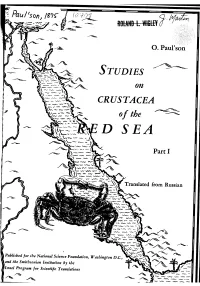

Studies Crustacea

^ Paul'son J /SIS- lO'^O ROLAND L. WICLEY f-¥ O. Paul'son STUDIES CRUSTACEA Translated Russian 1 Published for the National Science Foundation, Washington D.C., and the Smithsonian Institution by the I Israel Program for Scientific Translations y^^ X%b. HSCI^OBAHia PAK00EPA3HHX1) KPACHAFO MOPH Cl SAHtTKAMK OTHOCXTEJbNO PAXOOEPASHUXl iPUIXl HOPti (IZSLEDOVANIYA RAKOOBRAZNYKH KRASNAGO MORYA s zametkami otnositel'no rakoobraznykh drugikh morei) 0. nayyibcoHa (O. Paul'sona) ^ACTB I ( CHAST' 1 ) Podophthalmata H Edriophthalmata (Cumacca) (Podophthalmata i Edriophthalmata (Cumacea) ) { s dvadtsat'yu odnoyu tablitseyu risunkov ) —•—-•»—<apBSfe=—»i"—•— KIEBl Tuuoi']ui|iiji C. H. Ky.ibXEHKo HO Majo->KuTOMHpcKO& yi., x. X 63 1875 ( Tipografiya S. V. Kul'zhenko po Malo - Zhitomirskoi Ulitse, dom N 83) ( KIEV, 18 75 ) STUDIES on CRUSTACEA of the RED SEA with notes regarding other seas O. Paul'son PART I Podophthalmata and Edriophthalmata (Cumacea) with 21 tables KIEV Printed by S. V.Kurzhenko, 83 Malo-Zhitomirskaya Street 1875 OTS 60-21821 Publ ished for THE NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION, WASHINGTON, D.C. and SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, USA by THE ISRAEL PROGRAM FOR SCIENTIFIC TRANSLATIONS 1961 Title of Russian Original: Izsledovaniya rakoobraznvkh krasnago morya s zametkami otnositel'no rakoobraznykh drugikh morei Translated by: Francis D. For, M. Sc. Printed in Jerusalem by S. Monson PST Cat. No 232 Price: $1.75 (NOTE: Wherever genera and species were given in Latin in the Russian original they were reproduced without change, except where printing errors had to be corrected. Thus, certain genera and species are given differently in the Introduction and in the text proper, as for instance, in the case of Thalamita admete in the Introduction, but Thalamita Admete in the text.] Available from The Office of Technical Services U.S. -

Hairdressers Market 1226 Hollis Halifax, NS 425-3225 25% OFF All Curling Irons

00 0 0 c:'\; ('I') ('\J PAGE 2 >141-08 GAZETTE ···STAFF WEEKLY GAZETTE STArr EDITOR-IN-CHIEF' Julie Sobowale DISPATCH [email protected] COPY EDITOR Katie May co py@da Igazette. ca Hello, Dalhousie students! NEWS EDITORS Ruth Mestechkm We would like to congratulate the University on i ts t wo Melissa Di Costanzo recent environmental awards. Dalhousie i s t he first [email protected] university to receive the EcoLogo Envi ronmental COVER OPINIONS EDITOR Stewardship Award, which recognizes the uni versity's The Gazette's layout des1gner Susan Bethany Horne switch earlier this year to green cleaning products. We Maroun IS gallvanting around New York [email protected] have also been recognized by the Sustainable Endowments this week . a pnme opportunity for the ARTS & CULTURE EDITORS Institute with the Champi on of Sustainability in rest of the staff to comment on the Christie Conway Communities Award for the work done by the university's smooth production of this 1ssue. In the Hilary Beaumont [email protected] Eco-Efficiency Centre. Congrats and keep up the good five days since our design dictator has work! Your students and your environment thank you. been shopping, dnnking and spend SPORTS EDITOR ing money, no one has left the office Nick Khattar [email protected] Here at the DSU we also take pride in sustainability. The 1n tears, no one has partaken in any DSU sustainability office is a student-run space that ~creaming matches, and our bruises PHOTO EDITORS aids and engages the student body in education, have had a week to heal. -

Alien Species in the Mediterranean Sea by 2010

Mediterranean Marine Science Review Article Indexed in WoS (Web of Science, ISI Thomson) The journal is available on line at http://www.medit-mar-sc.net Alien species in the Mediterranean Sea by 2010. A contribution to the application of European Union’s Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). Part I. Spatial distribution A. ZENETOS 1, S. GOFAS 2, M. VERLAQUE 3, M.E. INAR 4, J.E. GARCI’A RASO 5, C.N. BIANCHI 6, C. MORRI 6, E. AZZURRO 7, M. BILECENOGLU 8, C. FROGLIA 9, I. SIOKOU 10 , D. VIOLANTI 11 , A. SFRISO 12 , G. SAN MART N 13 , A. GIANGRANDE 14 , T. KATA AN 4, E. BALLESTEROS 15 , A. RAMOS-ESPLA ’16 , F. MASTROTOTARO 17 , O. OCA A 18 , A. ZINGONE 19 , M.C. GAMBI 19 and N. STREFTARIS 10 1 Institute of Marine Biological Resources, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, P.O. Box 712, 19013 Anavissos, Hellas 2 Departamento de Biologia Animal, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Ma ’laga, E-29071 Ma ’laga, Spain 3 UMR 6540, DIMAR, COM, CNRS, Université de la Méditerranée, France 4 Ege University, Faculty of Fisheries, Department of Hydrobiology, 35100 Bornova, Izmir, Turkey 5 Departamento de Biologia Animal, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Ma ’laga, E-29071 Ma ’laga, Spain 6 DipTeRis (Dipartimento per lo studio del Territorio e della sue Risorse), University of Genoa, Corso Europa 26, 16132 Genova, Italy 7 Institut de Ciències del Mar (CSIC) Passeig Mar tim de la Barceloneta, 37-49, E-08003 Barcelona, Spain 8 Adnan Menderes University, Faculty of Arts & Sciences, Department of Biology, 09010 Aydin, Turkey 9 c\o CNR-ISMAR, Sede Ancona, Largo Fiera della Pesca, 60125 Ancona, Italy 10 Institute of Oceanography, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, P.O. -

Pipe Dreams Local Boarder Goes Pro and Brands His Own Board

17 09 / / 03 2009 VOLUME 64 Everything but the books How libraries are staying sexy Arts & Culture page 17 Forget about bribing your prof and make friends with Gundars Reinfelds Diplomas campus news page 6 for dummies Are feelings more important than knowledge? news page 2 Pipe dreams Local boarder goes pro and brands his own board Arts And Culture page 15 02 The UniTer September 17, 2009 www.UniTer.ca "I lived in the Chelsea Hotel How to pick your band LookInG FoR LIstInGs? Cover Image and the people you bump up after a nasty run-in CAmpus, Community And volunteer opportunities page 6 "Grey swallows green" by Johnny Mingo. catch Mingo's work at the into while roaming the halls musiC page 12 with Lord Voldemort winnipeg art Gallery's sales and GAlleries, theAtre, dAnCe And have rainbow vibrations." disguised as your manager. rentals area and in the "12 inch Comedy page 9 5" show at the edge Gallery at 611 Film And literAture page 13 Arts & Culture page 16 Arts & Culture page 18 Main Street. check out his work on Facebook @ "the art of MINGO." UNITER STAFF news ManaGinG eDitor Vacant » [email protected] BUSiness ManaGer James D. Patterson » [email protected] PrODUcTiOn ManaGer Graduation without the grades Melody Morrissette » [email protected] cOPy anD styLe eDitor Chris Campbell » [email protected] Social promotion in Photo eDitor "the education Mark Reimer » [email protected] schools is leaving system should focus newS assiGnMenT eDitor kids without skills, on the promotion Andrew McMonagle » [email protected] of self-worth rather newS PrODUcTiOn eDitor report says Cameron MacLean » [email protected] than the promotion arts anD culture eDitor of self-esteem." Aaron Epp » [email protected] eThaN CaBel -Ken JOhnS, PSychology PrOFessor, cOMMents eDitor BeaT reporTer UniverSiTy OF winniPeG Andrew Tod » [email protected] Listings cOOrDinator J.P. -

Exotic Species in the Aegean, Marmara, Black, Azov and Caspian Seas

EXOTIC SPECIES IN THE AEGEAN, MARMARA, BLACK, AZOV AND CASPIAN SEAS Edited by Yuvenaly ZAITSEV and Bayram ÖZTÜRK EXOTIC SPECIES IN THE AEGEAN, MARMARA, BLACK, AZOV AND CASPIAN SEAS All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission from the Turkish Marine Research Foundation (TÜDAV) Copyright :Türk Deniz Araştırmaları Vakfı (Turkish Marine Research Foundation) ISBN :975-97132-2-5 This publication should be cited as follows: Zaitsev Yu. and Öztürk B.(Eds) Exotic Species in the Aegean, Marmara, Black, Azov and Caspian Seas. Published by Turkish Marine Research Foundation, Istanbul, TURKEY, 2001, 267 pp. Türk Deniz Araştırmaları Vakfı (TÜDAV) P.K 10 Beykoz-İSTANBUL-TURKEY Tel:0216 424 07 72 Fax:0216 424 07 71 E-mail :[email protected] http://www.tudav.org Printed by Ofis Grafik Matbaa A.Ş. / İstanbul -Tel: 0212 266 54 56 Contributors Prof. Abdul Guseinali Kasymov, Caspian Biological Station, Institute of Zoology, Azerbaijan Academy of Sciences. Baku, Azerbaijan Dr. Ahmet Kıdeys, Middle East Technical University, Erdemli.İçel, Turkey Dr. Ahmet . N. Tarkan, University of Istanbul, Faculty of Fisheries. Istanbul, Turkey. Prof. Bayram Ozturk, University of Istanbul, Faculty of Fisheries and Turkish Marine Research Foundation, Istanbul, Turkey. Dr. Boris Alexandrov, Odessa Branch, Institute of Biology of Southern Seas, National Academy of Ukraine. Odessa, Ukraine. Dr. Firdauz Shakirova, National Institute of Deserts, Flora and Fauna, Ministry of Nature Use and Environmental Protection of Turkmenistan. Ashgabat, Turkmenistan. Dr. Galina Minicheva, Odessa Branch, Institute of Biology of Southern Seas, National Academy of Ukraine. -

The Alien Brachyuran Atergatis Roseus (Decapoda

Marine Biodiversity Records, page 1 of 3. # Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2010 doi:10.1017/S1755267210000667; Vol. 3; e76; 2010 Published online The alien brachyuran Atergatis roseus (Decapoda: Xanthidae) in Rhodes Island (Greece) maria corsini-foka1 and maria-antonietta pancucci-papadopoulou2 1Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, Institute of Oceanography, Hydrobiological Station of Rhodes, Cos Street, 85100 Rhodes, Greece, 2Hellenic Centre for Marine Research-Institute of Oceanography, 19013 Anavyssos, Greece The first finding of the alien crab Atergatis roseus (Xanthidae) in Rhodes Island (Hellenic south-eastern Aegean Sea) is docu- mented, increasing to eleven the number of alien brachyurans present in the area, nine of them having Indo-Pacific origin. Due to its coloration, not in accordance with the literature, the specimen is described in detail. Keywords: Brachyura, Xanthidae, Atergatis roseus, alien introduction, lessepsian migration, Aegean Sea, Mediterranean Sea Submitted 31 December 2009; accepted 29 May 2010 During a survey of the benthic fauna along the eastern coasts notch (Figure 1C). Frontorbital width 0.37 times as wide as car- of Rhodes Island, a male specimen of the stone crab Atergatis apace. Orbit width 1/5 of front border. Posterior margin of car- roseus (Ru¨ppell, 1830) (Brachyura: Xanthidae) was caught on apace smaller than frontorbital width. Superior face of chela 26 July 2009, near Plimmiris Bay (coordinates 35855′38′′N bluntly crested, fingers spoon-tipped with three flutes, coxae 27851′37′′E), by the fishing boat ‘Captain Stavros’, with and ischium of chelipeds with small tuft of hairs, at the anterior trammel nets (26 mm mesh size). -

49 Inspirational Travel Secrets from the Top Travel Bloggers on the Internet Today

2010 49 Inspirational Travel Secrets From the Top Travel Bloggers on the Internet Today www.tripbase.com Front Cover Main Index Foreword Congratulations on downloading your Best Kept Travel Secrets eBook. You're now part of a unique collaborative charity project, the first of its kind to take place on the Internet! The Best Kept Travel Secrets project was initiated with just one blog post back in November 2009. Since then, over 200 of the most talented travel bloggers and writers across the globe have contributed more than 500 inspirational travel secrets. These phenomenal travel gems have now been compiled into a series of travel eBooks. Awe-inspiring places, insider info and expert tips... you'll find 49 amazing travel secrets within this eBook. The best part about this is that you've helped contribute to a great cause. About Tripbase Founded in May 2007, Tripbase pioneered the Internet's first "destination discovery engine". Tripbase saves you from the time-consuming and frustrating online travel search by matching you up with your ideal vacation destination. Tripbase was named Top Travel Website for Destination Ideas by Travel and Leisure magazine in November 2008. www.tripbase.com Copyright / Terms of Use: US eBook - 49 secrets - Release 1.02 (May 24th, 2010) | Use of this ebook subject to these terms and conditions. Tripbase Travel Secrets E-books are free to be shared and distributed according to this creative commons copyright . All text and images within the e-books, however, are subject to the copyright of their respective owners. Best Kept Travel Secrets 2010 Tripbase.com 2 Front Cover Main Index These Secrets Make Dirty Water Clean Right now, almost one billion people in the world don't have access to clean drinking water. -

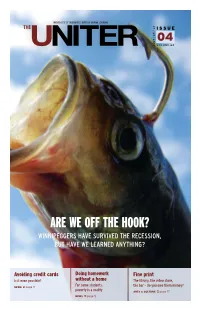

Avoiding Credit Cards Fine Print

24 09 / / 04 2009 VOLUME 64 Avoiding credit cards Doing homework Fine print Is it even possible? without a home The library, the video store, For some students, the bar – do you owe them money? news page 3 poverty is a reality arts & culture page 17 news page 5 02 The UniTer September 24, 2009 www.UniTer.ca Go green! Code of conduct: LooKInG FoR LIstInGs? Cover Image campus & community listings and Mickelthwate can't volunteer opportunities page 4 "namakan Lake Minnow" Win prizes! music page 12 wait to wave his baton galleries, theatre, dance and comedy page 13 Photograph by campus news page 6 arts & culture page 11 Film page 13, literature page 15 Bill Beso news UNITER STAFF ManaGinG eDitor Vacant » [email protected] BUSiness ManaGer Manitoba rejects harmonized sales tax Maggi Robinson » [email protected] PrODUcTiOn ManaGer Province would lose money if GST and PST amalgamate, finance minister says Melody Morrissette » [email protected] cOPy anD styLe eDitor Chris Campbell » [email protected] eThaN CaBel Photo eDitor Mark Reimer [email protected] BeaT reporTer » newS assiGnMenT eDitor Andrew McMonagle » [email protected] The Manitoba government has de- newS PrODUcTiOn eDitor cided that tax harmonization – a Cameron MacLean » [email protected] federal proposal to amalgamate the GST and the PST – will take away arts anD culture eDitor provincial tax control and hurt Aaron Epp » [email protected] consumers along the way. cOMMents eDitor “We are no longer considering Andrew Tod » [email protected] the option of an HST,” said Rosann Listings cOOrDinator Wowchuk, Manitoba minister of J.P. -

Kimberley Crusaders – Part 1 June 7/2018 – 2,119Km (1,324Miles) from Home

Kimberley Crusaders – Part 1 June 7/2018 – 2,119km (1,324miles) from home Hi welcome back everyone… Many of you have confirmed your anticipation in our travel tales ahead. Should there be anyone NOT wishing to receive these, please let us know; we will amend our mailing list, no questions asked! Figuring, we passed our six-month ‘Cape Crusader test run’ run last year, we decided to embark on a twelve-month stint this year. Maybe longer – depends on how we’ll adjust to the nomadic ways of gypsies in the longer term; look/see what life on the road will throw at us So… all a bit open-ended but we’ve done it: Our home is stripped bare and rented. Anyone toying with similar thoughts - One must not underestimate the monumental effort it takes of breaking free from societal life’s seemingly countless entrapments! Whose crazy idea exactly was this in the first place?! Hello golfers, proudly managed a “(w)hole in one”: Squeezing our entire possessions into one room. Credit to Katherine’s most skilful planning and removalists’ even more astonishing stacking skills. This is our vision Empty lounge room camping: Family farewell with sisters Jennifer, Charmaine and Brian FLASHBACK to April 3: In the meantime up north, the wet season has ended, the oppressive humidity disappeared and the welcome heat of the ‘dry’ has arrived beyond the Tropic Of Capricorn: The siren call of tropical Northern Australia beckons yet again. The dry season normally lasts for eight months: No rain, the bluest of blue skies and balmy nights.