The Use of Force Against Terrorists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arab Spring, Libyan Liberation and the Externally Imposed Democratic Revolution

Denver Law Review Volume 89 Issue 3 Special Issue - Constitutionalism and Article 7 Revolutions December 2020 Arab Spring, Libyan Liberation and the Externally Imposed Democratic Revolution Haider Ala Hamoudi Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation Haider Ala Hamoudi, Arab Spring, Libyan Liberation and the Externally Imposed Democratic Revolution, 89 Denv. U. L. Rev. 699 (2012). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. ARAB SPRING, LIBYAN LIBERATION AND THE EXTERNALLY IMPOSED DEMOCRATIC REVOLUTION HAIDER ALA HAMOUDIt For generations, the United States of America has played a unique role as an anchor of global security and advocate for human freedom. Mindful of the risks and costs of military action, we are naturally re- luctant to use force to solve the world's many challenges. But when our interests and values are at stake, we have a responsibility to act. -Barack Obama, March 28, 2011 (justifying the NATO intervention in Libya). I. INTRODUCTION Contemporary events in the Arab world should cause us to wonder what happened to our commitment to the democratic revolution. Ameri- ca's understanding of its own role in supporting democratic orders is, as a result of the so-called Arab Spring, as confused as it has ever been. I hope in these few pages to expound upon these ideas of democractic commitments and their consequences, which must command greater con- sideration. -

Israel's Rights As a Nation-State in International Diplomacy

Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Institute for Research and Policy המרכז הירושלמי לענייני ציבור ומדינה )ע"ר( ISRAEl’s RiGHTS as a Nation-State in International Diplomacy Israel’s Rights as a Nation-State in International Diplomacy © 2011 Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs – World Jewish Congress Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 13 Tel Hai Street, Jerusalem, Israel Tel. 972-2-561-9281 Fax. 972-2-561-9112 Email: [email protected] www.jcpa.org World Jewish Congress 9A Diskin Street, 5th Floor Kiryat Wolfson, Jerusalem 96440 Phone : +972 2 633 3000 Fax: +972 2 659 8100 Email: [email protected] www.worldjewishcongress.com Academic Editor: Ambassador Alan Baker Production Director: Ahuva Volk Graphic Design: Studio Rami & Jaki • www.ramijaki.co.il Cover Photos: Results from the United Nations vote, with signatures, November 29, 1947 (Israel State Archive) UN General Assembly Proclaims Establishment of the State of Israel, November 29, 1947 (Israel National Photo Collection) ISBN: 978-965-218-100-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Overview Ambassador Alan Baker .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The National Rights of Jews Professor Ruth Gavison ........................................................................................................................................................................... 9 “An Overwhelmingly Jewish State” - From the Balfour Declaration to the Palestine Mandate -

Peacekeeping Without the UN: the Multinational Force in Lebanon and International Law

Peacekeeping Without the UN: The Multinational Force in Lebanon and International Law Brian L. Zimblert The concept of peacekeeping' entails a fundamental contradiction, since its success depends upon the deployment of soldiers to deter armed conflict.2 Some notable peacekeeping efforts since World War II have sought to overcome this contradiction by stressing their impartial char- acter, and by adopting procedures designed to guarantee the neutral be- havior of their forces.3 Most such peacekeeping missions have been established and conducted under UN auspices,4 on the assumption that an international body could best approximate the neutral, detached per- spective ideally suited to successful peacekeeping. Indeed, UN-spon- sored missions have reinforced this assumption by adopting a legal and technical framework which enhanced their reputation as neutral inter- venors. While the appearance of neutrality has not always averted con- troversy in peacekeeping efforts,5 it has generally increased their chances t J.D. Candidate, Harvard University; M.A.L.D. Candidate, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. 1. The concept of peacekeeping was developed by Lester Pearson, then-UN Secretary- General Dag Hammarskjold, and General E.L.M. Burns for application in the Suez crisis of 1956. See 1 S. BAILEY, How WARS END: THE UNITED NATIONS AND THE TERMINATION OF ARMED CONFLICT, 1946-1964 at 268-71 (1982). It evolved from the earlier notion of "peace observation," i.e., the sending of neutral observers to monitor truces and cease-fires, as first used by the UN in Indonesia, Kashmir, and Palestine. See generally D. WAINHOUSE, INTERNATIONAL PEACE OBSERVATION: A HISTORY AND FORECAST (1966). -

Islamist Militant Groups in Post-Qadhafi Libya Post-Qadhafi Libya by Alison Pargeter by Alison Pargeter

FEBRUARY 2013 . VOL 6 . ISSUE 2 Contents Islamist Militant Groups in FEATURE ARTICLE 1 Islamist Militant Groups in Post-Qadhafi Libya Post-Qadhafi Libya By Alison Pargeter By Alison Pargeter REPORTS 5 Yemen’s Use of Militias to Maintain Stability in Abyan Province By Casey L. Coombs 7 Deciphering the Jihadist Presence in Syria: An Analysis of Martyrdom Notices By Aaron Y. Zelin 11 British Fighters Joining the War in Syria By Raffaello Pantucci 15 Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan’s New Cease-Fire Offer By Imtiaz Ali 18 The Significance of Maulvi Nazir’s Death in Pakistan By Zia Ur Rehman 20 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 24 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts Libyans celebrate the second anniversary of the Libyan uprising at Martyrs Square on February 17, 2013, in Tripoli. - AFP/Getty Images n july 2012, Libya held its first and currents have emerged in the post- national elections since the fall of Qadhafi era, including those at the Mu`ammar Qadhafi. The Libyan extreme end of the spectrum that have people, however, appeared to taken advantage of central authority Ibuck the trend of the Arab Spring by weakness by asserting power in their not electing an Islamist1 parliament. own local areas. This is particularly the Although Islamists are present in case in the east of the country, which the newly-elected General National has traditionally been associated with About the CTC Sentinel Congress, they are just one force among Islamist activism. The Combating Terrorism Center is an many competing in the political arena.2 independent educational and research While Islamists have not succeeded in Given the murky and chaotic nature of institution based in the Department of Social dominating Libya’s nascent political Libya’s transition, which has prompted Sciences at the United States Military Academy, scene, they have come to represent an the mushrooming of local power West Point. -

Libya: Unrest and U.S. Policy

Libya: Unrest and U.S. Policy Christopher M. Blanchard Acting Section Research Manager July 6, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33142 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Libya: Unrest and U.S. Policy Summary Over 40 years ago, Muammar al Qadhafi led a revolt against the Libyan monarchy in the name of nationalism, self-determination, and popular sovereignty. Opposition groups citing the same principles are now revolting against Qadhafi to bring an end to the authoritarian political system he has controlled in Libya for the last four decades. The Libyan government’s use of force against civilians and opposition forces seeking Qadhafi’s overthrow sparked an international outcry and led the United Nations Security Council to adopt Resolution 1973, which authorizes “all necessary measures” to protect Libyan civilians. The United States military is participating in Operation Unified Protector, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military operation to enforce the resolution. Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan and other partner governments also are participating. Qadhafi and his supporters have described the uprising as a foreign and Islamist conspiracy and are attempting to outlast their opponents. Qadhafi remains defiant amid coalition air strikes and defections. His forces continue to attack opposition-held areas. Some opposition figures have formed an Interim Transitional National Council (TNC), which claims to represent all areas of the country. They seek foreign political recognition and material support. Resolution 1973 calls for an immediate cease-fire and dialogue, declares a no-fly zone in Libyan airspace, and authorizes robust enforcement measures for the arms embargo on Libya established by Resolution 1970 of February 26. -

Rethinking Solutions for Palestinian Refugees a Much-Needed Paradigm Shift and an Opportunity Towards Its Realization

WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 135 Rethinking solutions for Palestinian refugees A much-needed paradigm shift and an opportunity towards its realization Francesca P Albanese and Lex Takkenberg [email protected] / [email protected] May 2021 Refugee Studies Centre Oxford Department of International Development University of Oxford RSC Working Paper Series The Refugee Studies Centre (RSC) Working Paper Series is intended to aid the rapid distribution of work in progress, research findings and special lectures by researchers and associates of the RSC. Papers aim to stimulate discussion among the worldwide community of scholars, policymakers and practitioners. They are distributed free of charge in PDF format via the RSC website. The opinions expressed in the papers are solely those of the author/s who retain the copyright. They should not be attributed to the project funders or the Refugee Studies Centre, the Oxford Department of International Development or the University of Oxford. Comments on individual Working Papers are welcomed, and should be directed to the author/s. Further details can be found on the RSC website (www.rsc.ox.ac.uk). RSC WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 135 About the authors Francesca P Albanese is an international lawyer, and currently the Coordinator of the Question of Palestine Programme hosted by Jordan-based organization Arab Renaissance for Democracy and Development (ARDD). She is an Affiliate Scholar at the International Study of International Migration (ISIM), Georgetown University and a Visiting Scholar at the Issam Fares Institute for Public Studies Policies and International Affairs, American University of Beirut. For 15 years, she has worked in the field of human rights and refugee protection, particularly in the Arab world: with the Department of Legal Affairs of UNRWA, UN agency for Palestinian refugees, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the European Union, the UN Development Programme, and various NGOs. -

Proportionality in War: Protecting Soldiers from Enemy Captivity, and Israel’S Operation Cast Lead—“The Soldiers Are Everyone’S Children”

OSIEL PROOF V6 10/31/2013 12:24 PM PROPORTIONALITY IN WAR: PROTECTING SOLDIERS FROM ENEMY CAPTIVITY, AND ISRAEL’S OPERATION CAST LEAD—“THE SOLDIERS ARE EVERYONE’S CHILDREN” ZIV BOHRER† AND MARK OSIEL I. INTRODUCTION On October 18, 2011, Israel struck a prisoner-exchange agreement with the Palestinian organization Hamas: Israel released 1027 Palestinian prisoners (jointly responsible for the death of some six-hundred Israelis) in return for one Israeli soldier, Gilad Shalit.1 Past experience has amply proven that many of those released will return to further violence.2 Yet, within Israeli society, the deal was broadly accepted.3 Elsewhere, however, the reaction was quite different, with many of Israel’s most prominent and ardent supporters condemning the exchange.4 How are we to account for such disparate responses? What features of Israeli and, conversely, American society might explain this variation? Were foreign commentators correct in attributing the discrepancy to † Faculty of Law, Bar Ilan University; Research Fellow 2012-2013, Sacher Institute, Faculty of Law, Hebrew University; Visiting Research Scholar 2011–2012, University of Michigan Law School; Ph.D. 2012, Tel-Aviv University. This author wishes to thank the Fulbright Foundation for its support. All translations of sources originally in Hebrew are my own. * Aliber Family Chair, College of Law, University of Iowa; B.A. 1977, University of California, Berkeley; M.A. 1978, University of Chicago; J.D., Ph.D. 1987, Harvard University. 1. See Ronen Bergman, Gilad Shalit and the Rising Price of an Israeli Life, N.Y. TIMES MAG., Nov. 9, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/13/magazine/gilad-shalit-and-the-cost-of-an-israeli- life.html (describing the details of the exchange). -

Israel and the Occupied Territories: an Analysis of the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1989 Israel and the occupied territories: An analysis of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict Benjamin Wood University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Wood, Benjamin, "Israel and the occupied territories: An analysis of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict" (1989). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 63. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/jywr-10p5 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

REASSESSING CBRN THREATS in a CHANGING GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT Edited by Fei Su and Ian Anthony

REASSESSING CBRN THREATS IN A CHANGING GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT edited by fei su and ian anthony June 2019 STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIPRI is an independent international institute dedicated to research into conflict, armaments, arms control and disarmament. Established in 1966, SIPRI provides data, analysis and recommendations, based on open sources, to policymakers, researchers, media and the interested public. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. GOVERNING BOARD Ambassador Jan Eliasson, Chair (Sweden) Dr Dewi Fortuna Anwar (Indonesia) Dr Vladimir Baranovsky (Russia) Espen Barth Eide (Norway) Jean-Marie Guéhenno (France) Dr Radha Kumar (India) Dr Patricia Lewis (Ireland/United Kingdom) Dr Jessica Tuchman Mathews (United States) DIRECTOR Dan Smith (United Kingdom) Signalistgatan 9 SE-169 72 Solna, Sweden Telephone: + 46 8 655 9700 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.sipri.org Reassessing CBRN Threats in a Changing Global Environment edited by fei su and ian anthony June 2019 © SIPRI 2019 The views expressed here are the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of SIPRI. Contents Preface v Acknowledgements vii Abbreviations viii Executive Summary ix 1. Introduction by Fei Su and Ian Anthony 1 Part I. Responding to the threat of CBRN use: The case of chemical weapons 2. Trends in recent CBRN incidents by Sadik Toprak 3 3. Reassessing CBRN terrorism threats by Elena Dinu 8 4. Reassessing chemical weapon threats by Joseph Ballard 14 5. International actions against the threats of chemical weapons use: 20 A Japanese perspective by Tatsuya Abe 6. The role of the OPCW and the Syrian conflict: How the OPCW can 26 develop its cooperation with states parties by Åke Sellström Part II. -

5. the Palestinian Authority Security Forces and the Battle for Gaza

THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY SECURITY FORCES: PAST AND PRESENT CHALLENGES Francesco Dotti, (Research Assistant, ICT) Spring 2017 ABSTRACT The purpose of this work is to identify and discuss several dimensions which affect the effectiveness of the Palestinian Authority Security Forces in the field of security and counter- terrorism. The analysis will touch upon, in addition to technical and organizational aspects, also the historical, cultural and political background of the Palestinian society and the outcomes of the assistance provided by international actors, such as the United States and Italy. In doing so, it will be possible to better understand which are the main challenges faced by the Palestinian security system in a systematic way. There are two main conclusions to this research: 1) The Palestinian Authority Security Forces are still far from being considered a professional quasi-military corp; 2) Analyzing socio-political dimensions of the Palestinian case is fundamental in order to understand the environment from which the Palestinian security apparatus emerged and how it has evolved over the years. **The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT). 2 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 4 2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................... -

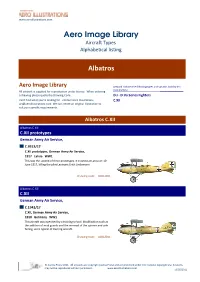

Aero Image Library Aircraft Types Alphabetical Listing

www.aeroillustrations.com Aero Image Library Aircraft Types Alphabetical listing Albatros Aero Image Library Artwork includes the following types and variants built by this manufacturer. All artwork is supplied for reproduction under licence. When ordering a drawing please quote the Drawing Code. D.I ‐ D.Va Series Fighters Can't find what you're looking for ‐ contact Aero Illustrations, C.XII [email protected]. We can create an original illustration to suit your specific requirements. Albatros C.XII Albatros C.XII C.XII prototypes German Army Air Service, C.9313/17 C.XII prototypes, German Army Air Service, 1917 Latvia WW1 This was the second of three prototypes. It crashed at Latvia on 10 June 1917, killing the pilot Leutnant Erich Lindemann. Drawing code: ALB12021 Albatros C.XII C.XII German Army Air Service, C.1942/17 C.XII, German Army Air Service, 1918 Germany WW1 This aircraft was operated by a training school. Modification such as the addition of mud guards and the removal of the spinner and axle fairing, were typical of training aircraft. Drawing code: ALB12011 © Juanita Franzi 2011. All artworks are copyright Juanita Franzi and are protected under international copyright law. Artworks may not be reproduced without permission. www.aeroillustrations.com 19/05/2011 Aero Image Library Albatros C.XII Page 2 of 388 [email protected] C.1972/17 C.XII, German Army Air Service, 1918 Bavaria WW1 This aircraft was the personal transportation of Major Stempel, the commander of all Bavarian Flieger‐Ersatz‐Abteilung or training units. Drawing code: ALB12032 Albatros D.I ‐ D.Va Series Fighters Albatros D.I ‐ D.Va Series Fighters Albatros D V German Army Air Service, Jasta 28 D.1154/17 Albatros D V, German Army Air Service, Jasta 28 Aug 1917 France WW1 Flown by Max Von Mueller, an ace with 38 victories. -

Proxy War Dynamics in Libya

PWP Confict Studies Proxy War Dynamics in Libya Jalel Harchaoui and Mohamed-Essaïd Lazib PWP Confict Studies The Proxy Wars Project (PWP) aims to develop new insights for resolving the wars that beset the Arab world. While the conflicts in Yemen, Libya, Syria, and Iraq have internal roots, the US, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and others have all provided mil- itary and economic support to various belligerents. PWP Conflict Studies are papers written by recognized area experts that are designed to elucidate the complex rela- tionship between internal proxies and external sponsors. PWP is jointly directed by Ariel Ahram (Virginia Tech) and Ranj Alaaldin (Brookings Doha Center) and funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Jalel Harchaoui is a research fellow at the Clingendael Institute in The Hague. His work focuses on Libya’s politics and security. Most of this essay was prepared prior to his joining Clingendael. Mohamed-Essaïd Lazib is a PhD candidate in geopolitics at University of Paris 8. His research concentrates on Libya’s armed groups and their sociology. Te views expressed are those of the authors alone and do not in any way refect the views of the institutions referred to or represented within this paper. Copyright © 2019 Jalel Harchaoui and Mohamed-Essaïd Lazib First published 2019 by the Virginia Tech School of Public and International Affairs in Association with Virginia Tech Publishing Virginia Tech School of Public and International Affairs, Blacksburg, VA 24061 Virginia Tech Publishing University Libraries at Virginia Tech 560 Drillfield Dr. Blacksburg, VA 24061 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21061/proxy-wars-harchaoui-lazib Suggested Citation: Harchaoui, J., and Lazib, M.