Mary Shelley's the Last Man," Sees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960S and Early 1970S

TV/Series 12 | 2017 Littérature et séries télévisées/Literature and TV series Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.2200 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Dennis Tredy, « Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s », TV/Series [Online], 12 | 2017, Online since 20 September 2017, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.2200 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series o... 1 Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy 1 In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, in a somewhat failed attempt to wrestle some high ratings away from the network leader CBS, ABC would produce a spate of supernatural sitcoms, soap operas and investigative dramas, adapting and borrowing heavily from major works of Gothic literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The trend began in 1964, when ABC produced the sitcom The Addams Family (1964-66), based on works of cartoonist Charles Addams, and CBS countered with its own The Munsters (CBS, 1964-66) –both satirical inversions of the American ideal sitcom family in which various monsters and freaks from Gothic literature and classic horror films form a family of misfits that somehow thrive in middle-class, suburban America. -

The Last Man"

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2016 Renegotiating the Apocalypse: Mary Shelley’s "The Last Man" Kathryn Joan Darling College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Darling, Kathryn Joan, "Renegotiating the Apocalypse: Mary Shelley’s "The Last Man"" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 908. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/908 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The apocalypse has been written about as many times as it hasn’t taken place, and imagined ever since creation mythologies logically mandated destructive counterparts. Interest in the apocalypse never seems to fade, but what does change is what form that apocalypse is thought to take, and the ever-keen question of what comes after. The most classic Western version of the apocalypse, the millennial Judgement Day based on Revelation – an absolute event encompassing all of humankind – has given way in recent decades to speculation about political dystopias following catastrophic war or ecological disaster, and how the remnants of mankind claw tooth-and-nail for survival in the aftermath. Desolate landscapes populated by cannibals or supernatural creatures produce the awe that sublime imagery, like in the paintings of John Martin, once inspired. The Byronic hero reincarnates in an extreme version as the apocalyptic wanderer trapped in and traversing a ruined world, searching for some solace in the dust. -

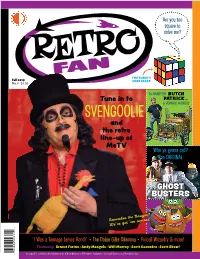

SVENGOOLIE and the Retro Line-Up of Metv Who Ya Gonna Call? the ORIGINAL

Are you too square to solve me? THE RUBIK'S Fall 2019 CUBE CRAZE No. 6 $8.95 The MUNSTERS’ BUTCH Tune in to PATRICK… & HORRIFIC HOTRODS SVENGOOLIE and the retro line-up of MeTV Who ya gonna call? The ORIGINAL GHOST BUSTERS Remember the Naugas? We’ve got ’em covered 2 2 7 3 0 0 “I Was a Teenage James Bond!” • The Dobie Gillis Dilemma • Pinball Wizardry & more! 8 5 6 2 Featuring Ernest Farino • Andy Mangels • Will Murray • Scott Saavedra • Scott Shaw! 8 Svengoolie © Weigel Broadcasting Co. Ghost Busters © Filmation. Naugas © Uniroyal Engineered Products, LLC. 1 The crazy cool culture we grew up with CONTENTS Issue #6 | Fall 2019 40 51 Columns and Special Features Departments 3 2 Retro Television Retrotorial Saturday Nights with 25 Svengoolie 10 RetroFad 11 Rubik’s Cube 3 Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Mornings 38 The Original Ghost Busters Retro Trivia Goldfinger 21 43 Oddball World of Scott Shaw! 40 The Naugas Too Much TV Quiz 25 59 Ernest Farino’s Retro Retro Toys Fantasmagoria Kenner’s Alien I Was a Teenage James Bond 21 74 43 Celebrity Crushes Scott Saavedra’s Secret Sanctum 75 Three Letters to Three Famous Retro Travel People Pinball Hall of Fame – Las Vegas, Nevada 51 65 Retro Interview 78 Growing Up Munster: RetroFanmail Butch Patrick 80 65 ReJECTED Will Murray’s 20th Century RetroFan fantasy cover by Panopticon Scott Saavedra The Dobie Gillis Dilemma 75 11 RetroFan™ #6, Fall 2019. Published quarterly by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. Michael Eury, Editor-in-Chief. John Morrow, Publisher. -

Gender, Authorship and Male Domination: Mary Shelley's Limited

CHAPITRE DE LIVRE « Gender, Authorship and Male Domination: Mary Shelley’s Limited Freedom in ‘‘Frankenstein’’ and ‘‘The Last Man’’ » Michael E. Sinatra dans Mary Shelley's Fictions: From Frankenstein to Falkner, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, p. 95-108. Pour citer ce chapitre : SINATRA, Michael E., « Gender, Authorship and Male Domination: Mary Shelley’s Limited Freedom in ‘‘Frankenstein’’ and ‘‘The Last Man’’ », dans Michael E. Sinatra (dir.), Mary Shelley's Fictions: From Frankenstein to Falkner, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, p. 95-108. 94 Gender cal means of achievement ... Castruccio will unite in himself the lion and the fox'. 13. Anne Mellor in Ruoff, p. 284. 6 14. Shelley read the first in May and the second in June 1820. She also read Julie, 011 la Nouvelle Héloïse (1761) for the third time in February 1820, Gender, Authorship and Male having previously read it in 1815 and 1817. A long tradition of educated female poets, novelists, and dramatists of sensibility extending back to Domination: Mary Shelley's Charlotte Smith and Hannah Cowley in the 1780s also lies behind the figure of the rational, feeling female in Shelley, who read Smith in 1816 limited Freedom in Frankenstein and 1818 (MWS/ 1, pp. 318-20, Il, pp. 670, 676). 15. On the entrenchment of 'conservative nostalgia for a Burkean mode] of a and The Last Man naturally evolving organic society' in the 1820s, see Clemit, The Godwinian Novel, p. 177; and Elie Halévy, The Liberal Awakening, 1815-1830, trans. E. Michael Eberle-Sinatra 1. Watkin (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1961) pp. 128-32. -

Sky Pilot, How High Can You Fly - Not Even Past

Sky Pilot, How High Can You Fly - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 19 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Sky Pilot, How High Can You Fly by Nathan Stone Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Confederacy” I started going to camp in 1968. We were still just children, but we already had Vietnam to think about. The evening news was a body count. At camp, we didn’t see the news, but we listened to Eric Burdon and the Animals’ Sky Pilot while doing our beadwork with Father Pekarski. Pekarski looked like Grandpa from The Munsters. He was bald with a scowl and a growl, wearing shorts and an official camp tee shirt over his pot belly. The local legend was that at night, before going out to do his vampire thing, he would come in and mix up your beads so that the red ones were in the blue box, and the black ones were in the white box. Then, he would twist the thread on your bead loom a hundred and twenty times so that it would be impossible to work with the next day. And laugh. In fact, he was as nice a May 06, 2020 guy as you could ever want to know. More from The Public Historian BOOKS America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee (2019) April 20, 2020 More Books The Munsters Back then, bead-craft might have seemed like a sort of “feminine” thing to be doing at a boys’ camp. -

Mary Shelley

Mary Shelley Early Life Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley was born on August 30, 1797, the daughter of two prominent radical thinkers of the Enlightenment. Her mother was the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, and her father was the political philosopher William Godwin, best known for An Inquiry Concerning Political Justice. Unfortunately, Wollstonecraft died just ten days after her daughter’s birth. Mary was raised by her father and stepmother Mary Jane Clairmont. When she was 16 years old, Mary fell in love with the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who visited her father’s house frequently. They eloped to France, as Shelley was already married. They eventually married after two years when Shelley’s wife Harriet committed suicide. The Writing of Frankenstein In the summer of 1816, the Shelleys rented a villa close to that of Lord Byron in Switzerland. The weather was bad (Mary Shelley described it as “wet, ungenial” in her 1831 introduction to Frankenstein), due to a 1815 eruption of a volcano in Indonesia that disrupted weather patterns around the world. Stuck inside much of the time, the company, including Byron, the Shelleys, Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont, and Byron’s personal physician John Polidori, entertained themselves with reading stories from Fantasmagoriana, a collection of German ghost stories. Inspired by the stories, the group challenged themselves to write their own ghost stories. The only two to complete their stories were Polidori, who published The Vampyre in 1819, and Mary Shelley, whose Frankenstein went on to become one of the most popular Gothic tales of all time. -

Frankenstein, Matilda, and the Legacies of Godwin and Wollstonecraft

2 PAMELA CLEMIT Frankenstein, Matilda, and the legacies of Godwin and Wollstonecraft [My mother’s] greatness of soul & my father high talents have perpetually reminded me that I ought to degenerate as little as I could from those from whom I derived my being . my chief merit must always be derived, first from the glory these wonderful beings have shed [?around] me, & then for the enthusiasm I have for excellence & the ardent admiration I feel for those who sacrifice themselves for the public good. (L ii 4) In this letter of September 1827 to Frances Wright, the Scottish-born author and social reformer, Mary Shelley reveals just how much she felt her life and thought to be shaped by the social and political ideals of her parents, William Godwin, the leading radical philosopher of the 1790s, and his wife, the proto-feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft. The multiple liter- ary, political, and philosophical influences of Godwin and Wollstonecraft may be traced in all six of Mary Shelley’s full-length novels, as well as in her tales, biographies, essays, and other shorter writings. Yet while she con- sistently wrote within the framework established by her parents’ concerns, she was no mere imitator of their works. Writing with an awareness of how French revolutionary politics had unfolded through the Napoleonic era, Mary Shelley extends and reformulates the many-sided legacies of Godwin and Wollstonecraft in extreme, imaginatively arresting ways. Those legacies received their most searching reappraisal in Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), Mary Shelley’s remarkable first novel, and were re- examined a year later in Matilda, a novella telling the story of incestuous love between father and daughter, which, though it remained unpublished until 1959, has now become one of her best-known works. -

Fracking (With) Post-Modernism, Or There's a Lil' Dr Frankenstein in All

1 Fracking (with) post-modernism, or there’s a lil’ Dr Frankenstein in all of us by Bryan Konefsky Since the dawn of (wo)mankind we humans have had the keen, pro-cinematic ability to assess our surroundings in ways not unlike the quick, rack focus of a movie camera. We move fluidly between close examination (a form of deconstruction) to a wide-angle view of the world (contextualizing the minutiae of our dailiness within deep philosophical inquiries about the nature of existence). To this end, one could easily infer that Dziga Vertov’s kino-eye might be a natural outgrowth of human evolution. However, we should be mindful of obvious and impetuous conclusions that seem to lead – superficially – to the necessity of a kino-prosthesis. In terms of a kino-prosthesis, the discomfort associated with a camera-less experience is understood, especially in a world where, as articulated so well by thinkers such as Sherry Turkle or Marita Sturken, one impulsively records information as proof of experience (see Turkle’s Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology and Less From Each Other and Sturken’s Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture). The unsettling nature of a camera-less experience reminds me of visionary poet Lisa Gill (see her text Caput Nili), who once told me about a dream in which she and Orson Welles made a movie. The problem was that neither of them had a camera. Lisa is quick on her feet so her solution was simply to carve the movie into her arm. For Lisa, it is clear what the relationship is between a sharp blade and a camera, and the association abounds with metaphors and allusions to my understanding of the pro-cinematic human. -

The Last Man Ebook

THE LAST MAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mary Shelley,Pamela Bickley,Dr. Keith Carabine | 432 pages | 05 Nov 2004 | Wordsworth Editions Ltd | 9781840224030 | English | Herts, United Kingdom The Last Man PDF Book Mary Shelley used this term in a letter of 3 October Director: Robert Sparr. Clear your history. USA Today. April 5, Release Dates. Legendas - Danilo Carvalho. Retrieved July 11, From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved September 26, Add the first question. For other uses, see The Last Man disambiguation. Genres: Western. Y: The Last Man at Wikipedia's sister projects. The series is collected in trade paperbacks. But one warning, if you are that fat, balding dufus, you will be miserable through out the film. After initially celebrating their reconnection, Yorick realizes he actually loves Society is plunged into chaos as infrastructures collapse, and the surviving women everywhere try to cope with the loss of the men, and the belief that, barring a rapid, major scientific breakthrough or other extraordinary happening, humanity is doomed to extinction. Adrian raises a military force against them and ultimately is able to resolve the situation peacefully. Plot Summary. His wife and kids were killed by soldiers in the Indian wars. Edit page. Arriving in Athens , Lionel learns that Raymond had been captured by the Ottomans , and negotiates his return to Greece. Fearing that is the last human left on Earth, Lionel follows the Apennine Mountains to Rome , befriending a sheepdog along the way. At age 85, Yorick is institutionalized following a joke interpreted as a suicide attempt. User Ratings. September — March This article is about the Mary Shelley novel. -

|||GET||| the Last Man 1St Edition

THE LAST MAN 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley | 9781420908954 | | | | | Last Man by Shelley, First Edition Paris, A. Mary Shelley. Idris descobre a armadilha e foge com Lionel, que se casa com ela logo depois. Growing up an orphan, Perdita was independent, distrustful, and proud, but she is softened by love for Raymond, to whom she is fiercely loyal. Edition originale. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska Press, Antes de sua morte, Evadne prediz a morte de Raymond, uma profecia que confirma as suspeitas de Raymond. As a six- year-old orphan, The Last Man 1st edition Raby prevents Rupert Falkner from committing suicide; Falkner then adopts her and brings her up to be The Last Man 1st edition model of virtue. Though now highly praised Muriel Spark thought it equal to, perhaps even better than, Frankensteinit was when first published violently condemned by reviewers, one calling it "the product of a diseased imagination and a polluted taste". The Last Man 1st edition book assumes that Greece would become independent but in later times go again to war with the Turks - which later decades indeed proved. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. The one scene with the hogs is the one most readers will never forget, and is based on fact. She is killed warning the other followers, after which the impostor commits suicide, and his followers return to the main body of exiles at Versailles. Individual reviewers labelled the book "sickening", criticised its "stupid cruelties", and called the author's imagination "diseased". However, he ultimately chooses his love for Perdita over his ambition, and the two marry. -

Read Book the Monsters Monster

THE MONSTERS MONSTER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Patrick McDonnell | 48 pages | 06 Sep 2012 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316045476 | English | New York, United States The Monsters Monster PDF Book More filters. After throwing dozens of quinceaneras for The Thing remains one of the most tense and heart-pounding sci-fi horror films ever made, thanks largely to its premise about an alien creature that can mimic other organic beings and assume their shape, appearance, and mannerisms. McDonnell writes a cute book about three little monsters who create their own monster, hoping he'll be really scary. They decide to create the biggest monster of all, so they get their Frankenstein on and bring a new monster to life. This is a must have and must read book. While every episode includes an unusual creature from a myth or urban legend, it's the underlying themes of family, betrayal, love, envy, greed and guilt that drive home the horror. While this episode has a real monster that lurks in the woods, the story isn't really about why or how her friend disappears. A Perfectly Messed-Up Story. The Blair Witch is at its most scary when it remains unseen and is used to psychologically torture the characters because audiences don't know who or what the Blair Witch actually is, even with the knowledge of the folklore behind it. The docudrama was created in the early '70s with a low budget, meaning that the footage was poor quality. Top-Rated Episodes S1. Daily Dead. A lovely story about meeting expectations, and friendship, and manners. -

Passive Angels and Miserable Devils Mary Shelley´S Frankenstein from a Historical, Political and Gender Perspective

2008:057 BACHELOR THESIS Passive Angels and Miserable Devils Mary Shelley´s Frankenstein from a Historical, Political and Gender Perspective Pernilla Fredriksson Luleå University of Technology Bachelor thesis English Department of Language and Culture 2008:057 - ISSN: 1402-1773 - ISRN: LTU-CUPP--08/057--SE Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 2 Acting a Novel The Life of the Author of Frankenstein ............................................................ 4 My Hideous Phantom The Novel ............................................................................................ 15 The Angel in the House Male and Female in Frankenstein ..................................................... 23 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ 33 Bibliography ............................................................................................................................. 35 Introduction Frankenstein and his creature are known to most people of our time. Still, not many know that the famous monster and his creator have their origin in a novel written by a young woman in the beginning of the nineteenth century. A challenge to write a ghost story 1 was the beginning of what came to be Mary Shelley’s most famous novel. Frankenstein, Or; The Modern Prometheus was written by a girl in a time when women were not supposed to