Doug Mcclemont Interview with Philip Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

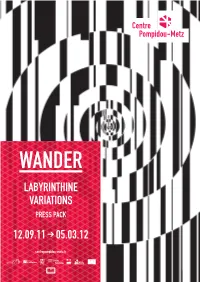

Labyrinthine Variations 12.09.11 → 05.03.12

WANDER LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS PRESS PACK 12.09.11 > 05.03.12 centrepompidou-metz.fr PRESS PACK - WANDER, LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION .................................................... 02 2. THE EXHIBITION E I TH LAByRINTH AS ARCHITECTURE ....................................................................... 03 II SpACE / TImE .......................................................................................................... 03 III THE mENTAL LAByRINTH ........................................................................................ 04 IV mETROpOLIS .......................................................................................................... 05 V KINETIC DISLOCATION ............................................................................................ 06 VI CApTIVE .................................................................................................................. 07 VII INITIATION / ENLIgHTENmENT ................................................................................ 08 VIII ART AS LAByRINTH ................................................................................................ 09 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ..................................................................... 10 4. LINEAgES, LAByRINTHINE DETOURS - WORKS, HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOgICAL ARTEFACTS .................... 12 5.Om C m ISSIONED WORKS ............................................................................. 13 6. EXHIBITION DESIgN ....................................................................................... -

With Their Pioneering Museum and All-For-One Approach, the Rubells Are the Art World’S Game Changers

FAMILY AFFAIR With their pioneering museum and all-for-one approach, the Rubells are the art world’s game changers. By Diane Solway Photographs by Rineke Dijkstra In 1981, on their regular rounds of New York’s East Vil- lage galleries and alternative spaces, the collectors Mera and Don Rubell struck up a friendship with a curator they’d met at the Mudd Club, a nexus of downtown cool. His name was Keith Haring, and he organized exhibitions upstairs. One day, in passing, he mentioned he was also an artist. At the time, Don, an obstetrician, and Mera, a teacher, lived on the Upper East Side with their two kids, Jason and Jennifer. Don’s brother Steve had cofounded Studio 54, the hottest disco on the planet, and artists would often refer to Don as “Steve Ru- bell’s brother, a doctor who collects new art with his wife.” The Rubells had begun buying art in 1964, the year they mar- ried, putting aside money each week to pay for it. Their limited funds led them to focus on “talent that hadn’t yet been discovered,” recalls George Condo, whose work they acquired early on. They loved talk- ing to artists, often spending hours in their studios. When they asked Haring if they could visit his, he told them he had nothing ready for them to see. But a few months later, he invited them to his first solo show, at Club 57. Struck by the markings Haring had made over iconic images of Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe, the Rubells asked to buy everything, only to learn that a guy named Jeffrey Deitch, an art ad- viser at Citibank, had arrived just ahead of them and snapped up a piece. -

Metro Pictures

METRO PICTURES Goldstein, Andrew. “American Gothic: Artist Robert Longo Gets His Revenge,” Man of the World (Fall 2016): Cover, 110-127. 519 WEST 24TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10011 T 212 206 7100 WWW.METROPICTURES.COM [email protected] American Gothic ARTIST ROBERT LONGO GETS HIS REVENGE UNTITLED (ST. LOUIS RAMS/HANDS UP) words by ANDREW GOLDSTEIN photography by BJÖRN WALLANDER 2015, charcoal on mounted paper, 65 x 120 inches opposite page: Artist Robert Longo, photographed in his studio in front of UNTITLED (PENTECOST), his 20-foot-long triptych of the robot from Pacific Rim, New York City, July 2016 The sign on the charcoal-blackened door sell for upward of a million dollars and He began taking night classes at Nassau of Robert Longo’s Little Italy studio reads are championed by people with names Community College, this time studying art SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES, but on a like Leo, Eli, and Dasha. Guardian critic history. “I distinctly remember going from recent Sunday afternoon, the artist presented Jonathan Jones has called his drawing of the kid who sat in the back of the class to being another side of what it means to be a refined, Ferguson police officers holding back black the kid who sat in the front. I really wanted if world-weary, badass. Dressed in black and protesters “the most important artwork to do this,” he says. After a summer visiting drinking a mug of tea—he foreswore alcohol of 2014.” This fall, Longo has a new show the museums of Europe and then acing a and drugs twenty years ago—Longo riffed on opening at Moscow’s Rem Koolhaas-designed battery of art-history tests, Longo transferred his work while giving a tour of his expansive Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, to SUNY Buffalo to pursue a bachelor’s in atelier, his confident gait somewhere between placing his work alongside that of two other fine arts. -

American Art 19 05 2021

INDEX Press release Fact Sheet Photo Sheet Exhibition Walkthrough Exhibition in figures American Art in Florence by Arturo Galansino, Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi Director General, and exhibition curator (excerpt from the essay in the catalog) American Art at the Walker, 1961-2001 by Vincenzo de Bellis, Curator and Associate Director of Programs, Visual Arts, Walker Art Center, and exhibition curator (excerpt from the essay in the catalog) A CLOSER LOOK The word to the artists Famous quotes from a selection of the artists of the exhibition: Mark Rothko, Louise Nevelson, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John Baldessari, Sherrie Levine, Kerry James Marshall, Cindy Sherman, Glenn Ligon, Matthew Barney, Kara Walker From art to society: three itineraries in the exhibition from the American Dream to the role of women and to art becoming political - The American Dream, - Art as a political struggle for identity and rights - The role of women in American art 1961-2001: 40 years of history and stories American Art on Demand Fuorimostra for American Art 1961-2001 List of the works AMERICAN ART 1961–2001 (Firenze, Palazzo Strozzi 28 May-29 August 2021) A major exhibition exploring some of the most important American artists from the 1960s to the 2000s, from Andy Warhol to Kara Walker, in partnership with The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis From 28 May to 29 August 2021 Palazzo Strozzi will present American Art 1961–2001, a major exhibition taking a new perspective on the history of contemporary art in the United States. The exhibition brings together an outstanding selection of more than 80 works by celebrated artists including Andy Warhol, Mark Rothko, Louise Nevelson, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Bruce Nauman, Barbara Kruger, Robert Mapplethorpe, Cindy Sherman, Matthew Barney, Kara Walker and many more, exhibited in Florence through a collaboration with the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. -

Metro Pictures

METRO PICTURES LEAVE CLOSED UPON PREMISES Welcome. We thank you for coming into Metro Pictures today. Please, close this booklet. Place it in your pocket, bag, purse, or hold on to it for later. Experience here. Thank you, and enjoy. METRO PICTURES 519 West 24th Street New York, NY 10011 Tuesday—Saturday, 10 AM—6 PM Or By Appointment T 212–206–7100 [email protected] https://www.metropictures.com Instagram @metro_pictures Twitter @MetroPictures GALLERY INFO GALLERY Metro Pictures was founded in 1980 by Janelle Reiring, formerly of Leo Castelli Gallery, and Helene Winer, formerly of Artists Space, at 169 Mercer Street in New York. The gallery’s inaugural exhibitions featured artists such as Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Louise Lawler, Sherrie Levine, James Welling, Richard Prince, and Walter Robinson – artists who would later be identified by critics and historians as Pictures artists. Many of them were prominently included in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2009 exhibition “The Pictures Generation.” In 1982 the gallery presented the first New York exhibition of Mike Kelley soon followed by shows of John Miller, Jim Shaw, and Gary Simmons – artists who would elaborate ideas proposed by the California conceptual artists with whom they had studied at CalArts. In 1983 the gallery relocated to 150 Greene Street. During this period, René Daniëls and Martin Kippenberger had their first exhibitions outside of Europe at the gallery. Metro Pictures moved to its present location in Chelsea in 1997 and in 2016 1100 Architects renovated the gallery with an award-winning new design. Newer generations of artists have continued to expand the gallery, including Andreas Slominski, Olaf Breuning, André Butzer, Isaac Julien, David Maljkovic, Paulina Olowska, Trevor Paglen, Catherine Sullivan, Sara VanDerBeek, Tris Vonna-Michell, B. -

Coleção Berardo (1960–2010)

Coleção Berardo (1960–2010) Vito Acconci Helena Almeida Carl Andre Giovanni Anselmo Art & Language Stephan Balkenhol Georg Baselitz Bernd & Hilla Becher Larry Bell Ashley Bickerton Alighiero Boetti Christian Boltanski Louise Bourgeois Marcel Broodthaers Daniel Buren Alberto Carneiro Alan Charlton James Coleman Tony Cragg Richard Deacon Stan Douglas Jimmie Durham Dan Flavin Hamish Fulton Gilbert & George Robert Gober Nan Goldin Dan Graham Andreas Gursky João Maria Gusmão e Pedro Paiva Jenny Holzer Rebecca Horn Donald Judd Anish Kapoor On Kawara Ellsworth Kelly Jeff Koons Joseph Kosuth Jannis Kounellis Guillermo Kuitca Sol LeWitt Richard Long Robert Mangold Agnes Martin Allan McCollum John McCracken Ana Mendieta Mario Merz Olivier Mosset Matt Mullican Juan Muñoz Bruce Nauman Manuel Ocampo Dennis Oppenheim Gabriel Orozco Tony Oursler Nam June Paik Gina Pane Pino Pascali Giuseppe Penone Michelangelo Pistoletto Sigmar Polke Richard Prince Pedro Cabrita Reis Gerhard Richter Rigo 23 Ulrich Rückriem Thomas Ruff Robert Ryman Julião Sarmento Richard Serra Cindy Sherman Ângelo de Sousa Ernesto de Sousa Haim Steinbach Frank Stella João Tabarra Rosemarie Trockel James Turrell Adriana Varejão Claude Viallat Pires Vieira Bill Viola Wolf Vostell Jeff Wall Sue Williams Gilberto Zorio This presentation of works from the collection is dedicated to the period that extends from 1960 to the present. The exhibition follows a chronological order, grouping together the most significant artistic movements of this the neo-vanguards: Minimalism, Conceptualism, Post-Minimalism, Land Art and Arte Povera, to name but a few. Over the course of these movements, the traditional categories that had previously defined the art object now underwent a profound transformation, one whose features had only been hinted at by the earlier, historic vanguards (shown on the second floor), and they were to undergo further reconfiguration in the years to come. -

From Minimalism to Performance Art: Chris Burden, 1967–1971

From Minimalism to Performance Art: Chris Burden, 1967–1971 Matthew Teti Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Matthew Teti All rights reserved ABSTRACT From Minimalism to Performance Art: Chris Burden, 1967–1971 Matthew Teti This dissertation was conceived as an addendum to two self-published catalogs that American artist Chris Burden released, covering the years 1971–1977. It looks in-depth at the formative work the artist produced in college and graduate school, including minimalist sculpture, interactive environments, and performance art. Burden’s work is herewith examined in four chapters, each of which treats one or more related works, dividing the artist’s early career into developmental stages. In light of a wealth of new information about Burden and the environment in which he was working in the late 1960s and early 1970s, this dissertation examines the artist’s work in relation to West Coast Minimalism, the Light and Space Movement, Environments, and Institutional Critique, above and beyond his well-known contribution to performance art, which is also covered herein. The dissertation also analyzes the social contexts in which Burden worked as having been informative to his practice, from the beaches of Southern California, to rock festivals and student protest on campus, and eventually out to the countercultural communes. The studies contained in the individual chapters demonstrate that close readings of Burden’s work can open up to formal and art-historical trends, as well as social issues that can deepen our understanding of these and later works. -

Metro Pictures

METRO PICTURES O’Hagan, Sean. “Cindy Sherman: ‘I enjoy doing the really difficult things that people can’t buy,’” TheGuardian.com (June 8, 2019). Untitled #74 by Cindy Sherman, 1980. Perhaps the most intriguing exhibit in Cindy Sherman’s forthcoming retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery is the first, Cindy Book, a family photo album she began making when she was just six years old. It comprises 26 snapshots pasted on pages torn out of a school exercise book and placed inside stapled-together plain covers that are now stained and discoloured with age. For all sorts of reasons, it is a good place to start. There is no artifice in the actual photographs. They trace ordinary moments in Sherman’s early life from infancy to adolescence: cute baby pics, family gatherings, snaps of her as a child at the beach and portraits of her as a teenager standing gauchely alongside awkward young men. What is striking is the sense of an almost stereotypical all-American suburban childhood. As is always the case with Sherman, though, nothing is quite what it seems. In green ink, she has circled herself in each photo and underneath written “That’s me,”. That comma is fascinating, perhaps a child’s grammatical error, yet already implying, as curator Paul Moorhouse notes in his catalogue essay, “an unfolding process.” When Sherman rediscovered Cindy Book as a 21-year-old art student, the process unfolded some more, as she added extra photos to the album and, as she puts it, made “the handwriting seem to grow up along with the images.” Does she consider the original handmade album the beginning of her long and singular art practice (“That’s me, or is it?”) or does it start in earnest with the later intervention? 519 WEST 24TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10011 T 212 206 7100 WWW.METROPICTURES.COM [email protected] Untitled #92 by Cindy Sherman, 1981. -

Jack Goldstein in Los Angeles

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 1-5-2018 Jack Goldstein in Los Angeles Kirby Michelle Woo CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/241 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Jack Goldstein in Los Angeles by Kirby Michelle Woo Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2017 Thesis Sponsor: January 3, 2018 Howard Singerman Date Signature January 3, 2018 Joachim Pissarro Date Signature of Second Reader i. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii List of Illustrations iii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 5 Chapter 2 24 Chapter 3 42 Conclusion 69 Bibliography 71 Illustrations 74 ii. Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the support of faculty and friends at Hunter College who have provided me guidance and encouragement throughout the years. I am especially thankful to my advisor Dr. Howard Singerman who actively participated in this project and provided the structure, insight, and critical feedback necessary to help me bring this work to completion. I am also grateful to Dr. Joachim Pissarro for his time as my second reader. I would also like to thank my editor, Viola McGowan for her patience and expertise, as well as Dr. David E. -

Oral History Interview with Richard Kuhlenschmidt, 2014 June 27

Oral history interview with Richard Kuhlenschmidt, 2014 June 27 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Richard Kuhlenschmidt on June 27, 2014. The interview took place in Santa Monica, California, and was conducted by Hunter Drohojowska-Philp for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Richard Kuhlenschmidt and Hunter Drohojowska-Philp have reviewed the transcript. Their corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview HUNTER DROHOJOWSKA-PHILP: This is Hunter Drohojowska-Philp interviewing Richard Kuhlenschmidt at the private beach club known as the Jonathan Club in Santa Monica, California, on June 27, 2014 for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, card number one. [Audio break.] HUNTER DROHOJOWSKA-PHILP: Here it is. You know, yes. It's this thing. This thing is blocking it. So, I'm going to have to do that whole thing over again. I'm really glad we checked that, though. RICHARD KUHLENSCHMIDT: So, why are you wearing the— HUNTER DROHOJOWSKA-PHILP: Well, I was putting it on to see if I was picking you up. But I think, actually, it's somehow, it's blocking the volume coming in. So, I'm going to start from the top. And you're going—basically, repeat that—it's only been two minutes. -

Athena Tacha: an Artist's Library on Environmental Sculpture and Conceptual

ATHENA TACHA: An Artist’s Library on Environmental Sculpture and Conceptual Art 916 titles in over 975 volumes ATHENA TACHA: An Artist’s Library on Environmental Sculpture and Conceptual Art The Library of Athena Tacha very much reflects the work and life of the artist best known for her work in the fields of environmental public sculpture and conceptual art, as well as photography, film, and artists’ books. Her library contains important publications, artists’ books, multiples, posters and documentation on environmental and land art, sculpture, as well as the important and emerging art movements of the sixties and seventies: conceptual art, minimalism, performance art, installation art, and mail art. From 1973 to 2000, she was a professor and curator at Oberlin College and its Art Museum, and many of the original publications and posters and exhibition announcements were mailed to her there, addressed to her in care of the museum (and sometimes to her colleague, the seminal curator Ellen Johnson, or her husband Richard Spear, the historian of Italian Renaissance art). One of the first artists to develop environmental site-specific sculpture in the early 1970s. her library includes the Berlin Land Art exhibition of 1969, a unique early “Seed Distribution Project” by the land and environmental artist Alan Sonfist, and a manuscript by Patricia Johanson. The library includes important and seminal exhibition catalogues from important galleries such as Martha Jackson’s “New Forms-New Media 1” from 1960. Canadian conceptual art is represented by N.E Thing, including the exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada, and the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design Projects Class cards, both in 1969. -

1. Janelle Reiring of Metro Pictures 2. Helene Winer of Metro Pictures 3

Indiana, Gary, “These ‘80s Artists Are More Important Than Ever,” T Magazine, February 13, 2017 Some of the key figures of the Pictures Generation, brought together in New York by T magazine on Dec. 10, 2016.Jason Schmidt 1. Janelle Reiring of Metro Pictures 2. Helene Winer of Metro Pictures 3. Hal Foster, critic 4. Douglas Crimp, critic 5. Robert Longo 6. Paul McMahon 7. Aura Rosenberg 8. John Miller 9. Troy Brauntuch 10. Sherrie Levine 11. David Salle 12. Nancy Dwyer 13. Glenn Branca 14. Cindy Sherman 15. James Welling 16. Laurie Simmons 17. Walter Robinson Images and technological media now pervade every minute of our lives so thoroughly that much of what passes for reality is indistinguishable from its representation. The urban environment is a cloaca of hypnotic, animated signage, sounds and image streams that follow us into taxicabs and hospital waiting rooms, and in turn, any banality, from a misspelled street sign to a funny advertisement, is considered suitable to become an image on social media. This didn’t happen overnight. One of the least helpful clichés of recent years has been the declaration that some phenomenon or person is “on the wrong side of history”; the presumption that history is headed, with occasional setbacks, toward a much-improved, even utopian state of things could only be endorsed by someone unfamiliar with history. Mistaking the perfection of our devices for the perfection of ourselves relieves us of responsibility for what happens to the world: It will just naturally turn out O.K., sooner or later. But technology can easily outrun our comprehension of what it does to us, even while it incarnates our wishes, fears and pathologies.