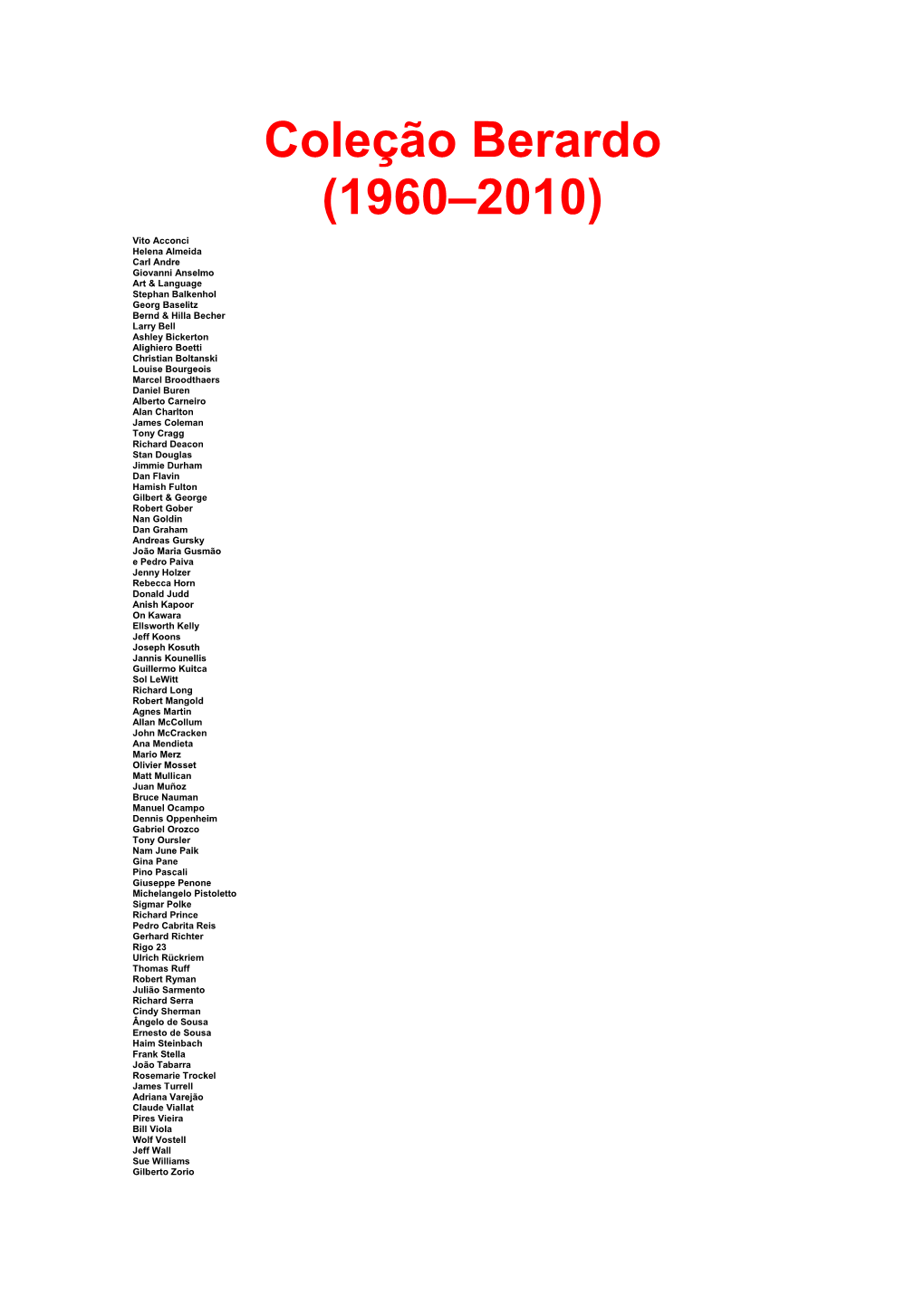

Coleção Berardo (1960–2010)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heiser, Jörg. “Do It Again,” Frieze, Issue 94, October 2005

Heiser, Jörg. “Do it Again,” Frieze, Issue 94, October 2005. In conversation with Marina Abramovic Marina Abramovic: Monica, I really like your piece Hausfrau Swinging [1997] – a video that combines sculpture and performance. Have you ever performed this piece yourself? Monica Bonvicini: No, although my mother said, ‘you have to do it, Monica – you have to stand there naked wearing this house’. I replied, ‘I don’t think so’. In the piece a woman has a model of a house on her head and bangs it against a dry-wall corner; it’s related to a Louise Bourgeois drawing from the ‘Femme Maison’ series [Woman House, 1946–7], which I had a copy of in my studio for a long time. I actually first shot a video of myself doing the banging, but I didn’t like the result at all: I was too afraid of getting hurt. So I thought of a friend of mine who is an actor: she has a great, strong body – a little like the woman in the Louise Bourgeois drawing that inspired it – and I knew she would be able to do it the right way. Jörg Heiser: Monica, after you first showed Wall Fuckin’ in 1995 – a video installation that includes a static shot of a naked woman embracing a wall, with her head outside the picture frame – you told me one critic didn’t talk to you for two years because he was upset it wasn’t you. It’s an odd assumption that female artists should only use their own bodies. -

Gina PANE: Action Psyché

Gina PANE: Action Psyché 30 May – 22 June 2019 Private view: Wednesday 29 May, 6–8pm “If I open my ‘body’ so that you can see your blood therein, it is for the love of you: the Other.” – Gina PANE, 1973 Gina Pane was instrumental to the development of the international Body Art movement, establishing a unique and corporeal language marked by ritual, symbolism and catharsis. The body, most often the artist’s own physical form, remained at the heart of her artistic practice as a tool of expression and communication until her death in 1990. Coming from the archives of the Galerie Rodolphe Stadler, the Parisian gallery of Pane who were themselves revolutionary in their presentation of avant-garde performance art, her exhibition at Richard Saltoun Gallery celebrates the artist’s pioneering career with a focus on the actions for which she is best known. It provides the most comprehensive display of the artist’s work in London since the Tate’s presentation in 2002. Exploring universal themes such as love, pain, death, spirituality and the metaphorical power of art, Pane sought to reveal and transform the way we have been taught to experience our body in relation to the self and others. She defined the body as “a place of the pain and suffering, of cunning and hope, of despair and illusion.” Her actions strived to reconnect the forces of the subconscious with the collective memory of the human psyche, and the sacred or spiritual. In these highly choreographed events, Pane subjected herself to intense physical and mental trials, which ranged from desperately seeking to drink from a glass of milk whilst tied, breaking the glass and lapping at the shards with her mouth (Action Transfert, 1973); piercing her arm with a neat line of rose thorns (Action Sentimentale, 1973); to methodically cutting her eyelids and stomach with razor blades (Action Psyché, 1974);and boxing with herself in front of a mirror (Action Il Caso no. -

Bob Flanagan, Sheree Rose and Masochistic Art During the NEA Controversies

BRING THE PAIN: Bob Flanagan, Sheree Rose and Masochistic Art during the NEA Controversies by LAURA MACDONALD BFA., Concordia University, 2003 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT GF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Art History, Visual Art and Theory UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA SEPTEMBER 2005 © Laura MacDonald, 2005 Abstract Poet, performance/installation artist, self-proclaimed "supermasochist" and life-long Cystic Fibrosis sufferer, Bob Flanagan and his partner, dominatrix and fellow artist Sheree Rose created art derived from their personal explorations of sadomasochistic sex acts and relationships. This work used the lens of S/M practice to deal with issues of illness, death, gender and sex. Throughout most of their 15 year collaboration (late 1980- early 1996) Flanagan and Rose lived and worked in relative obscurity, their work being circulated mainly in small subcultural circles. It was during the years of controversies surrounding the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), roughly 1989 to 1997, that Flanagan and Rose experienced unforeseen professional success and fame, propelling them from underground distribution in L.A. to the international art scene. These controversies arose from objections by various rightwing Christian politicians, individuals and groups who felt that the NEA had misused American tax dollars by awarding grants to artists who created and agencies that displayed "obscene" art. Flanagan and Rose were two such artists. This is a case study of the situation of Flanagan and Rose within these controversies, a situation in which there was opportunity, experimentation and heightened awareness despite (or perhaps because of) heated conflicts between opposing sets of ethics, aesthetics and lifestyle. -

Présence Réelle Et Figurée Du Sang Menstruel Chez Les Artistes Femmes : Les Pouvoirs Médusants De L'auto-Affirmation

Présence réelle et figurée du sang menstruel chez les artistes femmes : les pouvoirs médusants de l’auto-affirmation Emilie Bouvard « Enfin, de bafouillages en exclamations, nous parvînmes auprès du lit de la fille, prostrée, la malade, à la dérive. Je voulus l’examiner mais elle perdait tellement de sang, c’était une telle bouillie qu’on ne pouvait rien voir de son vagin. Des caillots. Çà faisait « glouglou » entre ses jambes comme dans le cou coupé du colonel à la guerre. Je remis le gros coton et remontai sa couverture simplement. (…) Pendant que [la mère] invoquait, provoquait le Ciel et l’Enfer, tonitruait de malheur, je baissais le nez et baissant déconfit je voyais se former sous le lit de la fille une petite flaque de sang, une mince rigole en suintait lentement le long du mur vers la porte. Une goutte du sommier chutait régulièrement. Tac ! tac ! Les serviettes entre ses jambes regorgeaient de rouge. »1 Ce passage du Voyage au bout de la Nuit de Louis-Ferdinand Céline n’évoque pas le sang menstruel mais une hémorragie mortelle suite à un avortement clandestin et dont Bardamu est au Raincy le témoin impuissant. Et pourtant, ce passage peut servir de fil conducteur dans cette étude du sang menstruel dans l’art féministe des années 1960 et 1970. En effet, ce sang qui coule à gros bouillons apparaît à bien des égards comme une version hallucinée et excessive du sang que perd la femme pendant les règles. Il s’agit d’une déperdition passive, incontrôlable, que l’on ne peut que juguler par des cotons et serviettes. -

Labyrinthine Variations 12.09.11 → 05.03.12

WANDER LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS PRESS PACK 12.09.11 > 05.03.12 centrepompidou-metz.fr PRESS PACK - WANDER, LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION .................................................... 02 2. THE EXHIBITION E I TH LAByRINTH AS ARCHITECTURE ....................................................................... 03 II SpACE / TImE .......................................................................................................... 03 III THE mENTAL LAByRINTH ........................................................................................ 04 IV mETROpOLIS .......................................................................................................... 05 V KINETIC DISLOCATION ............................................................................................ 06 VI CApTIVE .................................................................................................................. 07 VII INITIATION / ENLIgHTENmENT ................................................................................ 08 VIII ART AS LAByRINTH ................................................................................................ 09 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ..................................................................... 10 4. LINEAgES, LAByRINTHINE DETOURS - WORKS, HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOgICAL ARTEFACTS .................... 12 5.Om C m ISSIONED WORKS ............................................................................. 13 6. EXHIBITION DESIgN ....................................................................................... -

C#13 Modern & Contemporary Art Magazine 2013

2013 C#13 Modern & Contemporary Art Magazine C#13 O $PWFSJNBHF"MGSFEP+BBS 7FOF[JB 7FOF[JB EFUBJM Acknowledgements Contributors Project Managers Misha Michael Regina Lazarenko Editors Amy Bower Natasha Cheung Shmoyel Siddiqui Valerie Genty Yvonne Kook Weskott Designers Carrie Engerrand Kali McMillan Shahrzad Ghorban Zoie Yung Illustrator Zoie Yung C# 13 Advisory Board Alexandra Schoolman Cassie Edlefsen Lasch Diane Vivona Emily Labarge John Slyce Michele Robecchi Rachel Farquharson Christie's Education Staff Advisory Board John Slyce Kiri Cragin Thea Philips Freelance C#13 App Developer Pietro Romanelli JJ INDEX I Editor’s Note i British Art 29 Acknowledgements ii Kali McMillan Index iii Index iv Venice C#13 Emerging Artists 58 Robert Mapplethorpe's Au Debut (works form 1970 to 1979) Artist feature on Stephanie Roland at Xavier Hufkens Gallery Artist feature on De Monseignat The Fondation Beyeler Review Artist feature on Ron Muek LITE Art Fair Basel Review Beirut Art Center Review HK Art Basel review Interview with Vito Acconci More than Ink and Brush Interview with Pak Sheun Chuen Selling Out to Big Oil? Steve McQueen's Retrospective at Schaulager, Basel The Frozen Beginnings of Art Contemporary Arts as Alternative Culture Interview with Lee Kit (in traditional Chinese) A Failure to Communicate Are You Alright? Exhibition Review A Failure to Communicate Notes on Oreet Ashrey Keith Haring at Musee D’Art -

Oral History Interview with Suzanne Lacy, 1990 Mar. 16-Sept. 27

Oral history interview with Suzanne Lacy, 1990 Mar. 16-Sept. 27 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Suzanne Lacy on March 16, 1990. The interview took place in Berkeley, California, and was conducted by Moira Roth for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview has been extensively edited for clarification by the artist, resulting in a document that departs significantly from the tape recording, but that results in a far more usable document than the original transcript. —Ed. Interview [ Tape 1, side A (30-minute tape sides)] MOIRA ROTH: March 16, 1990, Suzanne Lacy, interviewed by Moira Roth, Berkeley, California, for the Archives of American Art. Could we begin with your birth in Fresno? SUZANNE LACY: We could, except I wasn’t born in Fresno. [laughs] I was born in Wasco, California. Wasco is a farming community near Bakersfield in the San Joaquin Valley. There were about six thousand people in town. I was born in 1945 at the close of the war. My father [Larry Lacy—SL], who was in the military, came home about nine months after I was born. My brother was born two years after, and then fifteen years later I had a sister— one of those “accidental” midlife births. -

With Their Pioneering Museum and All-For-One Approach, the Rubells Are the Art World’S Game Changers

FAMILY AFFAIR With their pioneering museum and all-for-one approach, the Rubells are the art world’s game changers. By Diane Solway Photographs by Rineke Dijkstra In 1981, on their regular rounds of New York’s East Vil- lage galleries and alternative spaces, the collectors Mera and Don Rubell struck up a friendship with a curator they’d met at the Mudd Club, a nexus of downtown cool. His name was Keith Haring, and he organized exhibitions upstairs. One day, in passing, he mentioned he was also an artist. At the time, Don, an obstetrician, and Mera, a teacher, lived on the Upper East Side with their two kids, Jason and Jennifer. Don’s brother Steve had cofounded Studio 54, the hottest disco on the planet, and artists would often refer to Don as “Steve Ru- bell’s brother, a doctor who collects new art with his wife.” The Rubells had begun buying art in 1964, the year they mar- ried, putting aside money each week to pay for it. Their limited funds led them to focus on “talent that hadn’t yet been discovered,” recalls George Condo, whose work they acquired early on. They loved talk- ing to artists, often spending hours in their studios. When they asked Haring if they could visit his, he told them he had nothing ready for them to see. But a few months later, he invited them to his first solo show, at Club 57. Struck by the markings Haring had made over iconic images of Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe, the Rubells asked to buy everything, only to learn that a guy named Jeffrey Deitch, an art ad- viser at Citibank, had arrived just ahead of them and snapped up a piece. -

From Happening to Performance

Philosophica 30, 1982 (2). pp. 61-74. 61 FROM HAPPENING TO PERFORMANCE Tadeusz Pawlowski Differences and Similarities The presence of the artist who in front of an audience perso nally carries out some actions is a feature shared by both manifes tations of contemporary art mentioned in the little, and at the same. time one of their important constitutive characters. There are more such common features; also, performance co-existed for some time together with happening, pushing it out gradually from the scene of world-art. In the face of such similarities and connections the more surprising are the essential differences which separate performance from happening. These differences refer to basic aims and functions as well as to artistic means used to realize them. Happeners strived to change the world: to make more humane the existing framework of social life; to abolish authoritarian conventic-~~ and customs which impoverished interhuman relations. They hoped to achieve this aim by penetrating the objective social world with their artistic actions. To make the actions maximally efficient it was necessary to integrate art in real life, to abolish the dividing line separating them. That is why happeners often carried out their actions at public places, frequented by great numbers of people : on busy streets 'and squares, at railway stations, airports, etc. Also at places where phenomena of common life provoked happeners' protests, because of their absurdity or cruelty, e.g. at slaughter-houses, in slums, at places of exuberant wealth. In· their effort to assimilate art to real life happeners admitted chance as. a factor determining their artistic decisions, because, as .they say, life is also governed by chance. -

ON PAIN in PERFORMANCE ART by Jareh Das

BEARING WITNESS: ON PAIN IN PERFORMANCE ART by Jareh Das Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Geography Royal Holloway, University of London, 2016 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Jareh Das hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 19th December 2016 2 Acknowledgments This thesis is the result of the generosity of the artists, Ron Athey, Martin O’Brien and Ulay. They, who all continue to create genre-bending and deeply moving works that allow for multiple readings of the body as it continues to evolve alongside all sort of cultural, technological, social, and political shifts. I have numerous friends, family (Das and Krys), colleagues and acQuaintances to thank all at different stages but here, I will mention a few who have been instrumental to this process – Deniz Unal, Joanna Reynolds, Adia Sowho, Emmanuel Balogun, Cleo Joseph, Amanprit Sandhu, Irina Stark, Denise Kwan, Kirsty Buchanan, Samantha Astic, Samantha Sweeting, Ali McGlip, Nina Valjarevic, Sara Naim, Grace Morgan Pardo, Ana Francisca Amaral, Anna Maria Pinaka, Kim Cowans, Rebecca Bligh, Sebastian Kozak and Sabrina Grimwood. They helped me through the most difficult parts of this thesis, and some were instrumental in the editing of this text. (Jo, Emmanuel, Anna Maria, Grace, Deniz, Kirsty and Ali) and even encouraged my initial application (Sabrina and Rebecca). I must add that without the supervision and support of Professor Harriet Hawkins, this thesis would not have been completed. -

Exhibiting Performance Art's History

EXHIBITING PERFORMANCE ART’S HISTORY Harry Weil 100 Years (version #2, ps1, nov 2009), a group show at MoMA PS1, Long Island City, New York, November 1, 2009 –May 3, 2010 and Off the Wall: Part 1—Thirty Performative Actions, a group show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, July 1–September 19, 2010. he past decade has born witness 100 Years, curated by MoMA PS1 cura- to the proliferation of perfor- tor Klaus Biesenbach and art historian mance art in the broadest venues RoseLee Goldberg, structured a strictly Tyet seen, with notable retrospectives of linear history of performance art. A Marina Abramović, Gina Pane, Allan five-inch thick straight blue line ran the Kaprow, and Tino Sehgal held in Europe length of the exhibition, intermittently and North America. Performance has pierced by dates written in large block garnered a space within the museum’s letters. The blue path mimics the simple hallowed halls, as these institutions have red and black lines of Alfred Barr’s chart hurriedly begun collecting performance’s on the development of modern art. Barr, artifacts and documentation. As such, former director of MoMA, created a museums play an integral role in chroni- simple scientific chart for the exhibition cling performance art’s little-detailed Cubism and Abstract Art (1935) that history. 100 Years (version #2, ps1, nov streamlines the genealogy of modern 2009) at MoMA PS1 and Off the Wall: art with no explanatory text, reduc- Part 1—Thirty Performative Actions at ing it to a chronological succession of the Whitney Museum of American avant-garde movements. -

Forms and Conceptions of Reality in French Body Art of the 1970S Clélia Barbut

Forms and Conceptions of Reality in French Body Art of the 1970s Clélia Barbut To cite this version: Clélia Barbut. Forms and Conceptions of Reality in French Body Art of the 1970s. Ownreality, 2015, 10. hal-01254583 HAL Id: hal-01254583 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01254583 Submitted on 12 Jan 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. OwnReality (10) Publication of the research project “To each his own reality.The notion of the real in the fine arts of France,West Germany, East Germany and Poland, 1960-1989” Clélia Barbut Forms and Conceptions of Reality in French Body Art of the 1970s Translated from the French by Sarah Tooth Michelet Editor: Mathilde Arnoux Chief editor: Clément Layet Assistant managing editor: Sira Luthardt Layout: Jacques-Antoine Bresch Warning This digital document has been made available to you by perspectivia.net, the international online publishing platform for the institutes of the MaxWeber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland (Max Weber Foundation – German Humanities Institutes Abroad) and its part- ners. Please note that this digital document is protected by copyright laws. The viewing, printing, downloading or storage of its content on your per- sonal computer and/or other personal electronic devices is authorised exclu- sively for private, non-commercial purposes.