One to One Performance a Study Room Guide on Works Devised for an ‘Audience of One’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Are We There Yet?

ARE WE THERE YET? Study Room Guide on Live Art and Feminism Live Art Development Agency INDEX 1. Introduction 2. Lois interviews Lois 3. Why Bodies? 4. How We Did It 5. Mapping Feminism 6. Resources 7. Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION Welcome to this Study Guide on Live Art and Feminism curated by Lois Weaver in collaboration with PhD candidate Eleanor Roberts and the Live Art Development Agency. Existing both in printed form and as an online resource, this multi-layered, multi-voiced Guide is a key component of LADA’s Restock Rethink Reflect project on Live Art and Feminism. Restock, Rethink, Reflect is an ongoing series of initiatives for, and about, artists who working with issues of identity politics and cultural difference in radical ways, and which aims to map and mark the impact of art to these issues, whilst supporting future generations of artists through specialized professional development, resources, events and publications. Following the first two Restock, Rethink, Reflect projects on Race (2006-08) and Disability (2009- 12), Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three (2013-15) is on Feminism – on the role of performance in feminist histories and the contribution of artists to discourses around contemporary gender politics. Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three has involved collaborations with UK and European partners on programming, publishing and archival projects, including a LADA curated programme, Just Like a Woman, for City of Women Festival, Slovenia in 2013, the co-publication of re.act.feminism – a performing archive in 2014, and the Fem Fresh platform for emerging feminist practices with Queen Mary University of London. Central to Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three has been a research, dialogue and mapping project led by Lois Weaver and supported by a CreativeWorks grant. -

Heiser, Jörg. “Do It Again,” Frieze, Issue 94, October 2005

Heiser, Jörg. “Do it Again,” Frieze, Issue 94, October 2005. In conversation with Marina Abramovic Marina Abramovic: Monica, I really like your piece Hausfrau Swinging [1997] – a video that combines sculpture and performance. Have you ever performed this piece yourself? Monica Bonvicini: No, although my mother said, ‘you have to do it, Monica – you have to stand there naked wearing this house’. I replied, ‘I don’t think so’. In the piece a woman has a model of a house on her head and bangs it against a dry-wall corner; it’s related to a Louise Bourgeois drawing from the ‘Femme Maison’ series [Woman House, 1946–7], which I had a copy of in my studio for a long time. I actually first shot a video of myself doing the banging, but I didn’t like the result at all: I was too afraid of getting hurt. So I thought of a friend of mine who is an actor: she has a great, strong body – a little like the woman in the Louise Bourgeois drawing that inspired it – and I knew she would be able to do it the right way. Jörg Heiser: Monica, after you first showed Wall Fuckin’ in 1995 – a video installation that includes a static shot of a naked woman embracing a wall, with her head outside the picture frame – you told me one critic didn’t talk to you for two years because he was upset it wasn’t you. It’s an odd assumption that female artists should only use their own bodies. -

Commencement 2006-2011

2009 OMMENCEMENT / Conferring of Degrees at the Close of the 1 33rd Academic Year Johns Hopkins University May 21, 2009 9:15 a.m. Contents Order of Procession 1 Order of Events 2 Divisional Ceremonies Information 6 Johns Hopkins Society of Scholars 7 Honorary Degree Citations 12 Academic Regalia 15 Awards 17 Honor Societies 25 Student Honors 28 Candidates for Degrees 33 Please note that while all degrees are conferred, only doctoral graduates process across the stage. Though taking photos from vour seats during the ceremony is not prohibited, we request that guests respect each other's comfort and enjoyment by not standing and blocking other people's views. Photos ol graduates can he purchased from 1 lomcwood Imaging and Photographic Services (410-516-5332, [email protected]). videotapes and I )\ I )s can he purchased from Northeast Photo Network (410 789-6001 ). /!(• appreciate your cooperation! Graduates Seating c 3 / Homewood Field A/ Order of Seating Facing Stage (Left) Order of Seating Facing Stage (Right) Doctors of Philosophy and Doctors of Medicine - Medicine Doctors of Philosophy - Arts & Sciences Doctors of Philosophy - Advanced International Studies Doctors of Philosophy - Engineering Doctors of Philosophy, Doctors of Public Health, and Doctors of Masters and Certificates -Arts & Sciences Science - Public Health Masters and Certificates - Engineering Doctors of Philosophy - Nursing Bachelors - Engineering Doctors of Musical Arts and Artist Diplomas - Peabody Bachelors - Arts & Sciences Doctors of Education - Education Masters -

Gina PANE: Action Psyché

Gina PANE: Action Psyché 30 May – 22 June 2019 Private view: Wednesday 29 May, 6–8pm “If I open my ‘body’ so that you can see your blood therein, it is for the love of you: the Other.” – Gina PANE, 1973 Gina Pane was instrumental to the development of the international Body Art movement, establishing a unique and corporeal language marked by ritual, symbolism and catharsis. The body, most often the artist’s own physical form, remained at the heart of her artistic practice as a tool of expression and communication until her death in 1990. Coming from the archives of the Galerie Rodolphe Stadler, the Parisian gallery of Pane who were themselves revolutionary in their presentation of avant-garde performance art, her exhibition at Richard Saltoun Gallery celebrates the artist’s pioneering career with a focus on the actions for which she is best known. It provides the most comprehensive display of the artist’s work in London since the Tate’s presentation in 2002. Exploring universal themes such as love, pain, death, spirituality and the metaphorical power of art, Pane sought to reveal and transform the way we have been taught to experience our body in relation to the self and others. She defined the body as “a place of the pain and suffering, of cunning and hope, of despair and illusion.” Her actions strived to reconnect the forces of the subconscious with the collective memory of the human psyche, and the sacred or spiritual. In these highly choreographed events, Pane subjected herself to intense physical and mental trials, which ranged from desperately seeking to drink from a glass of milk whilst tied, breaking the glass and lapping at the shards with her mouth (Action Transfert, 1973); piercing her arm with a neat line of rose thorns (Action Sentimentale, 1973); to methodically cutting her eyelids and stomach with razor blades (Action Psyché, 1974);and boxing with herself in front of a mirror (Action Il Caso no. -

VIPAW Wall Texts

3rd Venice International Performance Art Week, 2016 Ouch – Pain and Performance A screening programme curated by Live Art Development Agency, London “I see pain as an inevitable byproduct of interesting performance.” Dominic Johnson According to Wikipedia ‘pain’ is an “unpleasant feeling often caused by intense or damaging stimuli…(it) motivates the individual to withdraw from damaging situations and to avoid similar experiences in the future.” But for many artists and audiences the opposite is just as true, and pain within the context of performance is a challenging, exhilarating and profound experience. Ouch is a collection of documentation and artists’ films looking at pain and performance. The works are not necessarily performances about pain, but in some way involve or invoke pain in their making or reading or experience - both the pain artists cause themselves within the course of their work, whether intentional or not, and the experiences of audiences as they are invited to inflict pain on artists or are subjected to pain and discomfort themselves. The selected works feature eminent and ground breaking artists from around the world whose practices address provocative issues including the lived experiences of illness, the aging female body, cosmetic surgery, addiction, embodied public protest, animalistic impulses, blood letting, staged fights, acts of self harm and flagellation, and what can happen when you invite audiences to be complicit in performance actions. Ouch featured artists: Marina Abramovic, Ron Athey, Marcel.Li Antunez Roca, Franko B, Wafaa Bilal, Rocio Boliver, Cassils, Bob Flanagan, Regina Jose Galindo, jamie lewis hadley, Nicola Hunter & Ernst Fischer, Oleg Kulik, Martin O’Brien, Kira O’Reilly, ORLAN, Petr Pavlensky. -

FAÇADE: ZONE A: Religion/Family

CHECKLIST for Participant Inc. February 14-April 4, 2021 Curated by Amelia Jones Archival and research assistance by Ana Briz, David Frantz, Hannah Grossman, Dominic Johnson, Maddie Phinney *** UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED ALL ITEMS ARE FROM THE RON ATHEY ARCHIVE*** ***NOTE: photographs are credited where authorship is known*** FAÇADE: Rear projection of “Esoterrorist” text by Genesis P’Orridge, edited and video mapped as a word virus, as projected in the final scene of Ron Athey’s Acephalous Monster, “Cephalophore: Entering the Forest,” 2018-19. Video graphics work by Studio Ouroboros, Berlin. ZONE A: Religion/Family This section of the exhibition features a key work expanding on Ron Athey’s family and religious upbringing as a would-be Pentacostal minister: his 2002 live multimedia performance installation Joyce, which is named after Athey’s mother. It also includes elements from Athey’s archive relating to Joyce—including two costumes from the live performance—and his life within and beyond his fundamentalist origin family (such as unpublished writings from his period of recovery in the 1980s, and the numerous flyers advertising fundamentalist revivals he attended). The section is organized around materials that evoke the mix of religiosity and dysfunctional (sexualized and incestuous) family dynamics Athey experienced as a child and wrote about in some of his autobiographical writings that are included in the catalogue, including Mary Magdalene Footwashing Set (1996), which was included in a group show at Western Project in Los Angeles in 2006 and in the Invisible Exports Gallery “Displaced Person” show in 2012, a former gallery just around the corner from Participant Inc.’s location. -

PDF Portfolio

2 Clunbury Str, London N1 6TT waterside [email protected] contemporary waterside-contemporary.com tel +44 2034170159 Oreet Ashery waterside contemporary Reactivating The Clean and The Unclean, the protagonists of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s revolutionary 1921 play Mystery-Bouffe, Ashery collaboratively produced a collection of ponchos and headgear. These humble forms of dress made from ubiquitous cleaning materials - dish cloths, wipes, dusters – are the uniforms of speculative purists and partisans, exploited labourers and heroes. Adorned with this couture collection, the cast expose themselves to the inevitable risk of becoming objectified fashion icons. Oreet Ashery The Un/Clean (mermaid) 2014 sculpture textile, paper, tape, metal, plaster installation view at waterside contemporary photo: Jack Woodhouse ASH106 waterside contemporary Reactivating The Clean and The Unclean, the protagonists of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s revolutionary 1921 play Mystery-Bouffe, Ashery collaboratively produced a collection of ponchos and headgear. These humble forms of dress made from ubiquitous cleaning materials - dish cloths, wipes, dusters – are the uniforms of speculative purists and partisans, exploited labourers and heroes. Adorned with this couture collection, the cast expose themselves to the inevitable risk of becoming objectified fashion icons. Oreet Ashery The Un/Clean (the world doesn't have to be as you want it to be/ pizza head) 2014 sculpture textile, paper, tape, metal, plaster installation view at waterside contemporary photo: Jack Woodhouse ASH099 waterside contemporary Reactivating The Clean and The Unclean, the protagonists of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s revolutionary 1921 play Mystery-Bouffe, Ashery collaboratively produced a collection of ponchos and headgear. These humble forms of dress made from ubiquitous cleaning materials - dish cloths, wipes, dusters – are the uniforms of speculative purists and partisans, exploited labourers and heroes. -

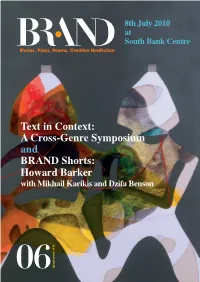

Howard Barker with Mikhail Karikis and Dzifa Benson

8th July 2010 at South Bank Centre Stories, Plays, Poems, Creative NonFiction Text in Context: A Cross-Genre Symposium and BRAND Shorts: Howard Barker with Mikhail Karikis and Dzifa Benson 06 Spring/Summer 2010 Text in Context: A Cross-Genre Symposium July 8th, Function Room, Level 5, Royal Festival Hall, 11am-5pm Programme Events are compered by Cherry Smyth Session 1 11am-12noon Sounding Stories: Anjan Saha, Jay Bernard & William Fontaine Chaired by: Anthony Joseph In the Frame and tablapoetry by Anjan Saha 01 Anjan Saha’s work In the Frame looks at diaspora identities and his tablapoetry brings ancient Indian rhythmic philosophy into present day focus. Poetry & comics by Jay Bernard 02 Jay Bernard will be reading three short poems, about pregnancy, childhood and pre-sexual desire, from two different books: - Your Sign is Cuckoo, Girl (“Kites” & “Eight”) - City State (“A Milken Bud”); accompanied by projections of comic strips. Diary of the Out: spoken word, sound work and 03 music by William Fontaine William Fontaine has crafted Diary of the Out, specially for this symposium, using his knowledge and synthesis of word, music, architecture and the esoteric. It is a short text (which will be expanded as a larger body of work) and soundwork, combining magical realism, non & science fi ction. Session 2 12-1pm Texted Image: Margareta Kern, Uriel Orlow, Oreet Ashery Chaired by: Cherry Smyth On being a guest by Margareta Kern 01 Kern will be discussing her current project ‘Guests’, based on the mass labour migration from the socialist Yugoslavia to West Germany in the late 1960’s. -

Bob Flanagan, Sheree Rose and Masochistic Art During the NEA Controversies

BRING THE PAIN: Bob Flanagan, Sheree Rose and Masochistic Art during the NEA Controversies by LAURA MACDONALD BFA., Concordia University, 2003 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT GF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Art History, Visual Art and Theory UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA SEPTEMBER 2005 © Laura MacDonald, 2005 Abstract Poet, performance/installation artist, self-proclaimed "supermasochist" and life-long Cystic Fibrosis sufferer, Bob Flanagan and his partner, dominatrix and fellow artist Sheree Rose created art derived from their personal explorations of sadomasochistic sex acts and relationships. This work used the lens of S/M practice to deal with issues of illness, death, gender and sex. Throughout most of their 15 year collaboration (late 1980- early 1996) Flanagan and Rose lived and worked in relative obscurity, their work being circulated mainly in small subcultural circles. It was during the years of controversies surrounding the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), roughly 1989 to 1997, that Flanagan and Rose experienced unforeseen professional success and fame, propelling them from underground distribution in L.A. to the international art scene. These controversies arose from objections by various rightwing Christian politicians, individuals and groups who felt that the NEA had misused American tax dollars by awarding grants to artists who created and agencies that displayed "obscene" art. Flanagan and Rose were two such artists. This is a case study of the situation of Flanagan and Rose within these controversies, a situation in which there was opportunity, experimentation and heightened awareness despite (or perhaps because of) heated conflicts between opposing sets of ethics, aesthetics and lifestyle. -

Présence Réelle Et Figurée Du Sang Menstruel Chez Les Artistes Femmes : Les Pouvoirs Médusants De L'auto-Affirmation

Présence réelle et figurée du sang menstruel chez les artistes femmes : les pouvoirs médusants de l’auto-affirmation Emilie Bouvard « Enfin, de bafouillages en exclamations, nous parvînmes auprès du lit de la fille, prostrée, la malade, à la dérive. Je voulus l’examiner mais elle perdait tellement de sang, c’était une telle bouillie qu’on ne pouvait rien voir de son vagin. Des caillots. Çà faisait « glouglou » entre ses jambes comme dans le cou coupé du colonel à la guerre. Je remis le gros coton et remontai sa couverture simplement. (…) Pendant que [la mère] invoquait, provoquait le Ciel et l’Enfer, tonitruait de malheur, je baissais le nez et baissant déconfit je voyais se former sous le lit de la fille une petite flaque de sang, une mince rigole en suintait lentement le long du mur vers la porte. Une goutte du sommier chutait régulièrement. Tac ! tac ! Les serviettes entre ses jambes regorgeaient de rouge. »1 Ce passage du Voyage au bout de la Nuit de Louis-Ferdinand Céline n’évoque pas le sang menstruel mais une hémorragie mortelle suite à un avortement clandestin et dont Bardamu est au Raincy le témoin impuissant. Et pourtant, ce passage peut servir de fil conducteur dans cette étude du sang menstruel dans l’art féministe des années 1960 et 1970. En effet, ce sang qui coule à gros bouillons apparaît à bien des égards comme une version hallucinée et excessive du sang que perd la femme pendant les règles. Il s’agit d’une déperdition passive, incontrôlable, que l’on ne peut que juguler par des cotons et serviettes. -

Oreet Ashery's Party for Freedom

Oreet Ashery Party for Freedom 07.09. - 27.10.2013 Oreet Ashery: Party for Freedom | An Audiovisual Album: Geert Wilders Triptych, 2013, video still The Unfinished Revolution: Oreet Ashery’s Party for Freedom By TJ Demos In ”Geert Wilders Triptych”, track 8 of Oreet extreme-right Partij voor de Vrijheid (Party Ashery’s hour-long video Party for Freedom for Freedom). As such, her moving-image | An Audiovisual Album (2013), a man is work, constituting ten interconnected tracks, shown chasing a woman around the grass, reveals what Fredric Jameson would call the grunting “Geert” as they go. Both are naked “political unconscious” of rightwing political and on all fours. Tracking his female prey in discourse, exposing its underlying “proble- this bizarre tale of sexual experimentation matics of ideology, of the unconscious and and political theatre – “Geert” references of desire, of representation, of history, and Dutch rightwing politician Geert Wilders – of cultural production.”1 the man kicks like a donkey, and eventually succeeds in grabbing her leg and bringing Coming after two years of research, As- her down face-first on the ground, as a dog hery’s video interweaves complex elements looks on and appears miffed by the curio- of experimental performance, nude theatre us display. Reminiscent of the scene of the and political satire, punk music and trash nude chase in The Idiots, Lars von Trier’s aesthetics, in order to deconstruct, via cut- 1998 comedy-drama film in which characters ting parody, the paradoxical ideology that attempt to get in touch with their inner-idiot joins the freedoms of sexual transgression to in a related critical acting-out of European the xenophobic and murderous intolerance libertarianism-become-libertinage, Ashery’s of outsiders. -

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: a Question of the Body and Its Reflections As Gesture

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: A Question of the Body and its Reflections as Gesture. ...material action is painting that has spread beyond the picture surface. The human body, a laid table or a room becomes the picture surface. Time is added to the dimension of the body and space. - "Material Action Manifesto," Otto Muhl, 1964 VIS 2 Winter 2017 When: Thursday: 6:30 p.m. to 8:20p.m. Where: PCYNH 106 Professor: Ricardo Dominguez Email: [email protected] Office Hour: Thursday. 11:00 a.m. to Noon. Room: VAF Studio 551 (2nd Fl. Visual Art Facility) The body-as-gesture has a long history as a site of aesthetic experimentation and reflection. Art-as-gesture has almost always been anchored to the body, the body in time, the body in space and the leftovers of the body This class will focus on the history of these bodies-as-gestures in performance art. An additional objective for the course will focus on the question of documentation in order to understand its relationship to performance as an active frame/framing of reflection. We will look at modernist, contemporary and post-contemporary, contemporary work by Chris Burden, Ulay and Abramovic, Allen Kaprow, Vito Acconci, Coco Fusco, Faith Wilding, Anne Hamilton, William Pope L., Tehching Hsieh, Revered Billy, Nao Bustamante, Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, Adrian Piper, Sophie Calle, Ron Athey, Patty Chang, James Luna, and the work of many other body artists/performance artists. Students will develop 1 performance action a week, for 5 weeks, for a total of 5 gestures/actions (during the first part of the class), individually or in collaboration with other students.