Oral History Interview with Richard Kuhlenschmidt, 2014 June 27

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diana Thater Born 1962 in San Francisco

David Zwirner This document was updated September 28, 2019. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Diana Thater Born 1962 in San Francisco. Lives and works in Los Angeles. EDUCATION 1990 M.F.A., Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, California 1984 B.A., Art History, New York University SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Diana Thater, The Watershed, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston 2017-2019 Diana Thater: A Runaway World, The Mistake Room, Los Angeles [itinerary: Borusan Contemporary, Istanbul; Guggenheim Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain] 2017 Diana Thater: The Starry Messenger, Moody Center for the Arts at Rice University, Houston, Texas 2016 Diana Thater, 1301PE, Los Angeles 2015 Beta Space: Diana Thater, San Jose Museum of Art, California Diana Thater: gorillagorillagorilla, Aspen Art Museum, Colorado Diana Thater: Life is a Timed-Based Medium, Hauser & Wirth, London Diana Thater: Science, Fiction, David Zwirner, New York Diana Thater: The Starry Messenger, Galerie Éric Hussenot, Paris Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination, Los Angeles County Museum of Art [itinerary: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago] [catalogue] 2014 Diana Thater: Delphine, Saint-Philibert, Dijon [organized by Fonds régional d’art contemporain Bourgogne, Dijon] 2012 Diana Thater: Chernobyl, David Zwirner, New York Diana Thater: Oo Fifi - Part I and Part II, 1310PE, Los Angeles 2011 Diana Thater: Chernobyl, Hauser & Wirth, London Diana Thater: Chernobyl, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia Diana Thater: Nature Morte, Galerie Hussenot, Paris Diana Thater: Peonies, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio 2010 Diana Thater: Between Science and Magic, David Zwirner, New York Diana Thater: Between Science and Magic, Santa Monica Museum of Art, California [catalogue] Diana Thater: Delphine, Kunstmuseum Stuttgart 2009 Diana Thater: Butterflies and Other People, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, California Diana Thater: Delphine, Kulturkirche St. -

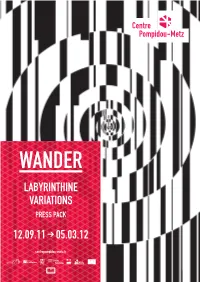

Labyrinthine Variations 12.09.11 → 05.03.12

WANDER LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS PRESS PACK 12.09.11 > 05.03.12 centrepompidou-metz.fr PRESS PACK - WANDER, LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION .................................................... 02 2. THE EXHIBITION E I TH LAByRINTH AS ARCHITECTURE ....................................................................... 03 II SpACE / TImE .......................................................................................................... 03 III THE mENTAL LAByRINTH ........................................................................................ 04 IV mETROpOLIS .......................................................................................................... 05 V KINETIC DISLOCATION ............................................................................................ 06 VI CApTIVE .................................................................................................................. 07 VII INITIATION / ENLIgHTENmENT ................................................................................ 08 VIII ART AS LAByRINTH ................................................................................................ 09 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ..................................................................... 10 4. LINEAgES, LAByRINTHINE DETOURS - WORKS, HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOgICAL ARTEFACTS .................... 12 5.Om C m ISSIONED WORKS ............................................................................. 13 6. EXHIBITION DESIgN ....................................................................................... -

Artists, Critics, Curators Speaker Series

Nasher Sculpture Center Announces Spring 2016 Line-up for 360: Artists, Critics, Curators Speaker Series Monthly speaker series explores topics of modern and contemporary art and design DALLAS, Texas (January 19, 2016) – The Nasher Sculpture Center is pleased to announce the line-up for the spring 2016 season of the Nasher speaker series, 360: Artists, Critics, Curators, which features conversations and lectures on the ever-expanding definition of sculpture and the thinking behind some of the world’s most innovative artwork, architecture, and design. The public is invited to join us for fresh understanding, insights and inspiring ideas. Lectures are free with museum admission: $10 for adults, $7 for seniors, $5 for students, and free for Members. Seating is limited, so reservations are requested. Immediately following the presentation, guests will enjoy a wine reception with RSVP. For information and reservations, email [email protected] or call 214.242.5159. Updates and information are available at www.NasherSculptureCenter.org/360. Monthly Lectures: Ann Veronica Janssens, Exhibition Artist Saturday, January 23, 11:30 am Known primarily as a light artist, Ann Veronica Janssens is interested in “situations of dazzlement… the persistence of vision, vertigo, saturation, speed, and exhaustion”—in other words, how the body responds to certain scientific phenomena and conditions put upon it. Janssens will speak on the opening day of her self-titled exhibition at the Nasher, the first one-person museum show in the United States for the Brussels-based artist. For the exhibition, she will install several sculptural works that allow viewers to encounter shifts in surface, depth, and color, challenging perception and destabilizing their sense of sight and space. -

FEVER DREAMS / / Interview with Andy Fabo

FEVER DREAMS / / Interview with Andy Fabo In a 1981 essay published in October, Benjamin Buchloh described contemporary artists engaged in figuration as “ciphers of regression,” artists whose practices represented a step backwards in the forward march of artistic progress. This prominent art historian, born in Germany and working now as a professor at Harvard, was employed at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD) when he wrote this essay, appointed head of the university press between 1978 and 1983.i Buchloh was in part reacting to the extreme heat of the neo-Expressionist market of the late 1970s and ‘80s, which in many ways mirrored the excesses of Wall Street at the time; New York Times critic Roberta Smith reflects that “The Neo-Expressionists were an instant hit. The phrases ‘art star’ ‘sellout show’ and ‘waiting list’ gained wide usage, sometimes linked to artists you’d barely heard of.”ii Buchloh, like Clement Greenberg had for the modernist generation before him, played an outsized role in the nascent post-modern scene in Canada. However, unlike Greenberg, the rapidly expanding field of artistic production in Canada prevented him from playing the singular role that Greenberg had during his time. Simply put, the proliferation of university studio programs and the coalescing of artistic communities in various urban centres allowed for a multiplicity of practices that had not existed in Canada prior to the 1970s. Fever Dreams, which presents figurative works drawn from the Permanent Collection of the MacLaren Art Centre and dating from 1978 to 2000, highlights a seismic shift from a virtually monolithic focus on abstraction at mid-century to the more pluralistic artistic practices of the latter quarter of the twentieth century. -

With Their Pioneering Museum and All-For-One Approach, the Rubells Are the Art World’S Game Changers

FAMILY AFFAIR With their pioneering museum and all-for-one approach, the Rubells are the art world’s game changers. By Diane Solway Photographs by Rineke Dijkstra In 1981, on their regular rounds of New York’s East Vil- lage galleries and alternative spaces, the collectors Mera and Don Rubell struck up a friendship with a curator they’d met at the Mudd Club, a nexus of downtown cool. His name was Keith Haring, and he organized exhibitions upstairs. One day, in passing, he mentioned he was also an artist. At the time, Don, an obstetrician, and Mera, a teacher, lived on the Upper East Side with their two kids, Jason and Jennifer. Don’s brother Steve had cofounded Studio 54, the hottest disco on the planet, and artists would often refer to Don as “Steve Ru- bell’s brother, a doctor who collects new art with his wife.” The Rubells had begun buying art in 1964, the year they mar- ried, putting aside money each week to pay for it. Their limited funds led them to focus on “talent that hadn’t yet been discovered,” recalls George Condo, whose work they acquired early on. They loved talk- ing to artists, often spending hours in their studios. When they asked Haring if they could visit his, he told them he had nothing ready for them to see. But a few months later, he invited them to his first solo show, at Club 57. Struck by the markings Haring had made over iconic images of Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe, the Rubells asked to buy everything, only to learn that a guy named Jeffrey Deitch, an art ad- viser at Citibank, had arrived just ahead of them and snapped up a piece. -

The Chronicling of Conceptual Art

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2011 Mythic Narratives: The hrC onicling of Conceptual Art Ana A. Iwataki Pitzer College Recommended Citation Iwataki, Ana A., "Mythic Narratives: The hrC onicling of Conceptual Art" (2011). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 1. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/1 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythic Narratives: The Chronicling of Conceptual Art by Ana Iwataki SUBMITTED TO PITZER COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR ARTS Professor Bill Anthes Professor Mark Allen Ciara Ennis April 25, 2011 Contents Acknowledgments iii Introduction: Location, Location, Location: Conceptual Art Past, Present, and Future 1 Chapter One: Artist Biographies and the Mythologized Narrative 14 Chapter Two: The Visible Narrative: Photography and Conceptual Art 32 Chapter Three: Parafictional Narratives: The Art World’s Oral Tradition 54 Conclusion: Beyond Conceptualism: The Capacity of Art’s Chronicle 73 Bibliography 77 ii Acknowledgments I am deeply grateful to my first reader Bill Anthes for being a voice of reason, patience, and guidance throughout this process. He provided early support when I had a different topic, helped me discover what I really wanted to write about, talked me down from panic when I felt behind schedule, reassured me that I knew what I was doing, and pointed me in the right direction when I didn’t. -

Richard Tuttle

RICHARD TUTTLE born 1941, Rahway, New Jersey lives and works in New York, NY and Abiquiú, NM EDUCATION 1963 Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut, BA SELECTED SOLO / TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS (* Indicates a publication) 2022 *What is the Object?, Bard Graduate Center, New York, NY 2021 Nine Stepping Stones, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2020 Stories, I-XX, Galerie Greta Meert, Brussels, Belgium TheStars, Modern Art, London, England 2019 Days, Muses and Stars, Pace Gallery, New York, NY *Basis, 70s Drawings, Pace Gallery, New York, NY Introduction to Practice, M Woods Museum, Beijing, China Double Corners and Colored Wood¸ Pace Gallery, Beijing, China 2018 For Ourselves As Well As For Others, Pace Gallery, Geneva, Switzerland 8 of Hachi, Tomio Koyama Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Intersections: Richard Tuttle. It Seems Like It’s Going To Be, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Thoughts of Trees, Pace Gallery, Seoul, South Korea 2017 100 Epigrams, Pace Prints, New York, NY Light and Color, Kunstmuseum aan Zee, Oostend, Belgium Books, Multiples, Prints, Writings and New Projects, Galerie Christian Lethert, Cologne, Germany The Critical Edge, Pace London, England My Birthday Puzzle, Modern Art, London, England De Hallen Haarlem, Haarlem, Netherlands [email protected] www.davidkordanskygallery.com T: 323.935.3030 F: 323.935.3031 2016 *Both/And Richard Tuttle Print and Cloth, Oklahoma State University Museum of Art, Stillwater, OK *Al Cielo de Noche de Lima / To the Night Sky of Lima, Proyecto AMIL and Museo de Arte de -

Elliott Hundley Bibliography

ELLIOTT HUNDLEY BIBLIOGRAPHY Selected Monographs: 2017 Nawi, Diana, Elliott Hundley: Movement V, published by Bernier/Eliades, and Agra Publications, Athens, Greece, 2017 2011 Bedford, Christopher, Anne Carson, Doug Harvey, and Richard Meyer, Elliott Hundley: The Bacchae, published by Wexner Center for the Arts, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, 2011 [ill.] Selected Catalogues and Publications: 2020 French, Christopher, David Scott Kastan, and David Pagel, Telling Stories: Reframing the Narratives, published by Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, NY, 2020, pp. 116 – 137 [ill., cover] 2015 Heyler, Joanne, ed., The Broad Collection, published by The Broad, Los Angeles, CA, and Prestel, New York, NY, 2015, pp. 329 [ill.] Baker, George, Ann Goldstein, Michael Maltzan, and Shaun Caley Regen, Regen Projects 25, published by Prestel, New York, NY, 2015 Artists in Their Time, published by Istanbul Museum of Modern Art, Istanbul, Turkey, 2015 2013 Lehan, Joanna, Kristen Lubben, and Carol Squiers, A Different Kind of Order: The ICP Triennial, published by the International Center of Photography, New York, NY, and DelMonico Books, New York, NY, 2013, pp. 86 – 89 Janssen, Hans and Bert Kreuk, Transforming the Known: Works from The Bert Kreuk Collection, published by Bert Kreuk and Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, Den Haag, Netherlands, 2013 2012 Tøjner, Poul Erik, Pink Caviar: New Acquisitions 2009-2011, published by Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark, 2012 2011 Doll, Nancy M., Weatherspoon Art Museum: 70 Years of Collecting, published -

Metro Pictures

METRO PICTURES Goldstein, Andrew. “American Gothic: Artist Robert Longo Gets His Revenge,” Man of the World (Fall 2016): Cover, 110-127. 519 WEST 24TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10011 T 212 206 7100 WWW.METROPICTURES.COM [email protected] American Gothic ARTIST ROBERT LONGO GETS HIS REVENGE UNTITLED (ST. LOUIS RAMS/HANDS UP) words by ANDREW GOLDSTEIN photography by BJÖRN WALLANDER 2015, charcoal on mounted paper, 65 x 120 inches opposite page: Artist Robert Longo, photographed in his studio in front of UNTITLED (PENTECOST), his 20-foot-long triptych of the robot from Pacific Rim, New York City, July 2016 The sign on the charcoal-blackened door sell for upward of a million dollars and He began taking night classes at Nassau of Robert Longo’s Little Italy studio reads are championed by people with names Community College, this time studying art SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES, but on a like Leo, Eli, and Dasha. Guardian critic history. “I distinctly remember going from recent Sunday afternoon, the artist presented Jonathan Jones has called his drawing of the kid who sat in the back of the class to being another side of what it means to be a refined, Ferguson police officers holding back black the kid who sat in the front. I really wanted if world-weary, badass. Dressed in black and protesters “the most important artwork to do this,” he says. After a summer visiting drinking a mug of tea—he foreswore alcohol of 2014.” This fall, Longo has a new show the museums of Europe and then acing a and drugs twenty years ago—Longo riffed on opening at Moscow’s Rem Koolhaas-designed battery of art-history tests, Longo transferred his work while giving a tour of his expansive Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, to SUNY Buffalo to pursue a bachelor’s in atelier, his confident gait somewhere between placing his work alongside that of two other fine arts. -

The Artist Interview As a Platform for Negotiating an Artwork's Possible

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The Artist Interview as a Platform for Negotiating an Artwork’s Possible Futures Wielocha, A. Publication date 2018 Document Version Final published version Published in Sztuka i Dokumentacja License CC BY Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wielocha, A. (2018). The Artist Interview as a Platform for Negotiating an Artwork’s Possible Futures. Sztuka i Dokumentacja, 17, 31-45. http://www.journal.doc.art.pl/pdf17/Art_and_Documentation_17_wielocha.pdf General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 Aga WIELOCHA University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam School for Heritage, Memory and Material Culture THE ARTIST INTERVIEW AS A PLATFORM FOR NEGOTIATING AN ARTWORK’S POSSIBLE FUTURES In the 1990s, Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, a chief conservator at the Menil Collection, started to interview artists in order to gather information about collected artworks for the sake of potential future conservation treatment. -

American Art 19 05 2021

INDEX Press release Fact Sheet Photo Sheet Exhibition Walkthrough Exhibition in figures American Art in Florence by Arturo Galansino, Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi Director General, and exhibition curator (excerpt from the essay in the catalog) American Art at the Walker, 1961-2001 by Vincenzo de Bellis, Curator and Associate Director of Programs, Visual Arts, Walker Art Center, and exhibition curator (excerpt from the essay in the catalog) A CLOSER LOOK The word to the artists Famous quotes from a selection of the artists of the exhibition: Mark Rothko, Louise Nevelson, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John Baldessari, Sherrie Levine, Kerry James Marshall, Cindy Sherman, Glenn Ligon, Matthew Barney, Kara Walker From art to society: three itineraries in the exhibition from the American Dream to the role of women and to art becoming political - The American Dream, - Art as a political struggle for identity and rights - The role of women in American art 1961-2001: 40 years of history and stories American Art on Demand Fuorimostra for American Art 1961-2001 List of the works AMERICAN ART 1961–2001 (Firenze, Palazzo Strozzi 28 May-29 August 2021) A major exhibition exploring some of the most important American artists from the 1960s to the 2000s, from Andy Warhol to Kara Walker, in partnership with The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis From 28 May to 29 August 2021 Palazzo Strozzi will present American Art 1961–2001, a major exhibition taking a new perspective on the history of contemporary art in the United States. The exhibition brings together an outstanding selection of more than 80 works by celebrated artists including Andy Warhol, Mark Rothko, Louise Nevelson, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Bruce Nauman, Barbara Kruger, Robert Mapplethorpe, Cindy Sherman, Matthew Barney, Kara Walker and many more, exhibited in Florence through a collaboration with the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. -

Metro Pictures

METRO PICTURES LEAVE CLOSED UPON PREMISES Welcome. We thank you for coming into Metro Pictures today. Please, close this booklet. Place it in your pocket, bag, purse, or hold on to it for later. Experience here. Thank you, and enjoy. METRO PICTURES 519 West 24th Street New York, NY 10011 Tuesday—Saturday, 10 AM—6 PM Or By Appointment T 212–206–7100 [email protected] https://www.metropictures.com Instagram @metro_pictures Twitter @MetroPictures GALLERY INFO GALLERY Metro Pictures was founded in 1980 by Janelle Reiring, formerly of Leo Castelli Gallery, and Helene Winer, formerly of Artists Space, at 169 Mercer Street in New York. The gallery’s inaugural exhibitions featured artists such as Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Louise Lawler, Sherrie Levine, James Welling, Richard Prince, and Walter Robinson – artists who would later be identified by critics and historians as Pictures artists. Many of them were prominently included in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2009 exhibition “The Pictures Generation.” In 1982 the gallery presented the first New York exhibition of Mike Kelley soon followed by shows of John Miller, Jim Shaw, and Gary Simmons – artists who would elaborate ideas proposed by the California conceptual artists with whom they had studied at CalArts. In 1983 the gallery relocated to 150 Greene Street. During this period, René Daniëls and Martin Kippenberger had their first exhibitions outside of Europe at the gallery. Metro Pictures moved to its present location in Chelsea in 1997 and in 2016 1100 Architects renovated the gallery with an award-winning new design. Newer generations of artists have continued to expand the gallery, including Andreas Slominski, Olaf Breuning, André Butzer, Isaac Julien, David Maljkovic, Paulina Olowska, Trevor Paglen, Catherine Sullivan, Sara VanDerBeek, Tris Vonna-Michell, B.