Jack Goldstein in Los Angeles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Michele Leigh Paper : Animated Music

GA2012 – XV Generative Art Conference Michele Leigh Paper : Animated Music: Early Experiments with Generative Art Abstract: This paper will explore the historical underpinnings of early abstract animation, more particularly attempts at visual representations of music. In order to set the stage for a discussion of the animated musical form, I will briefly draw connections to futurist experiments in art, which strove to represent both movement and music (Wassily Kandinsky for instance), as a means of illustrating a more explicit desire in animation to extend the boundaries of the art in terms of materials and/or techniques By highlighting the work of experimental animators like Hans Richter, Oskar Fishinger, and Mary Ellen Bute, this paper will map the historical connection between musical and animation as an early form of generative art. I will unpack the ways in which these filmmakers were creating open texts that challenged the viewer to participate in the creation of meaning and thus functioned as proto-generative art. Topic: Animation Finally, I will discuss the networked visual-music performances of Vibeke Sorenson as an artist who bridges the experimental animation Authors: tradition, started by Richter and Bute, and contemporary generative art Michele Leigh, practices. Department of Cinema & Photography This paper will lay the foundation for our understanding of the Southern Illinois history/histories of generative arts practice. University Carbondale www.siu.edu You can send this abstract with 2 files (.doc and .pdf file) to [email protected] or send them directly to the Chair of GA conferences [email protected] References: [1] Paul Wells, “Understanding Animation,” Routledge, New York, 1998. -

Download a Searchable PDF of This

Jack Goldstein; Distance Equals Control by David SaZZe This essay is offered as a compliment to the exhibition rather than an explication of specific works. The language used in this text is somewhat more general and anecdotal, and more given to metaphoric comparisons than what we have come to expect from art writing. I don't in this essay attempt to dissect a single ' - exemplar work, nor do I spend much time detailing the visual ,+ attributes of the works. This essay attempts instead to give a brief description of an ongoing process: the play of private fan- tasy, which itself grows out of the intersection of psychic necessity (desire)with the culturally available forms in which to voice that necessity (automaticity)becoming linked in a work of art to everyday, public images which then reenter and submerge themselves, via the appropriative nature of our attention, into a clouded pool of personal symbols. This three part process yields a two part result; a sense of control over what one has effected distance from, which is ironically expressed in a sense of anxiety embedded in the image used in a given work, and also a sense of sadness because of the loss one feels for the thing distanced. The result of this process is nostalgia for the present, which is the name given to a complex texture of imagizing in which mediation between extremes (differentiation) leads to a liberated use of symbol rather than more limited narrative notion of emblem. To consider this work at all involves thinking about a way to stand in relation to the use of images both rooted in and somewhat distanced from cultural seeing. -

Diana Thater Born 1962 in San Francisco

David Zwirner This document was updated September 28, 2019. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Diana Thater Born 1962 in San Francisco. Lives and works in Los Angeles. EDUCATION 1990 M.F.A., Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, California 1984 B.A., Art History, New York University SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Diana Thater, The Watershed, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston 2017-2019 Diana Thater: A Runaway World, The Mistake Room, Los Angeles [itinerary: Borusan Contemporary, Istanbul; Guggenheim Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain] 2017 Diana Thater: The Starry Messenger, Moody Center for the Arts at Rice University, Houston, Texas 2016 Diana Thater, 1301PE, Los Angeles 2015 Beta Space: Diana Thater, San Jose Museum of Art, California Diana Thater: gorillagorillagorilla, Aspen Art Museum, Colorado Diana Thater: Life is a Timed-Based Medium, Hauser & Wirth, London Diana Thater: Science, Fiction, David Zwirner, New York Diana Thater: The Starry Messenger, Galerie Éric Hussenot, Paris Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination, Los Angeles County Museum of Art [itinerary: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago] [catalogue] 2014 Diana Thater: Delphine, Saint-Philibert, Dijon [organized by Fonds régional d’art contemporain Bourgogne, Dijon] 2012 Diana Thater: Chernobyl, David Zwirner, New York Diana Thater: Oo Fifi - Part I and Part II, 1310PE, Los Angeles 2011 Diana Thater: Chernobyl, Hauser & Wirth, London Diana Thater: Chernobyl, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia Diana Thater: Nature Morte, Galerie Hussenot, Paris Diana Thater: Peonies, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio 2010 Diana Thater: Between Science and Magic, David Zwirner, New York Diana Thater: Between Science and Magic, Santa Monica Museum of Art, California [catalogue] Diana Thater: Delphine, Kunstmuseum Stuttgart 2009 Diana Thater: Butterflies and Other People, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, California Diana Thater: Delphine, Kulturkirche St. -

Harry Gregson-Williams

HARRY GREGSON-WILLIAMS AWARDS / NOMINATIONS IVOR NOVELLO AWARD NOMINATION (2011) UNSTOPPABLE Best Original Film Score ANNIE AWARD NOMINATION (2010) SHREK FOREVER AFTER Music in a Feature Production ACADEMY OF INTERACTIVE ARTS & METAL GEAR SOLID 4 SCIENCES AWARD (2009) Outstanding Achievement in Original Music INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC CRITICS CALL OF DUTY 4: MODERN WARFARE ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2007) Original Score for a Video Game or Interactive Media* WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWA RD SHREK THE THIRD NOMINATION Best Original Score of the Year (2007) WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWA RD DÉJÀ VU, SHREK THE THIRD, THE NUMBER 23, NOMINATION FLUSHED AWAY Film Composer of the Year (2007) GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA: Best Score Soundtrack Album (2006) THE LION, THE WITCH AND THE WARDROBE GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA: Best Original Score (2005) THE LION, THE WITCH AND THE WARDROBE BAFTA AWARD NOMINATION* Anthony Asquith Award for Achievement in Film SHREK Music (2002) ANNIE AWARD* SHREK Outstanding Achievement for Music Score in an Animated Feature (2001) * shared nomination The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency (818) 260-8500 1 HARRY GREGSON-WILLIAMS MOTION PICTURES EXODUS: GODS AND KINGS Peter Chernin / Mark Huffam / Michael Schaefer, prods. 20 th Century Fox Ridley Scott, dir. BLACKHAT Jon Jashni / Michael Mann / Thomas Tull, prods. Universal Pictures Michael Mann, dir. THE EQUALIZER Todd Black / Jason Blumenthal / Tony Eldridge / Sony Pictures Mace Neufeld / Alex Siskin / Michael Sloan / Steve Tisch / Denzel Washington / Richard Wenk, prods. Antoine Fuqua, dir. THE EAST Ben Howe / Brit Marling / Jocelyn Hayes-Simpson / Fox Michael Costigan, prods. *theme Zal Matmanglij, dir. TOTAL RECALL Toby Jaffe / Neal H. -

SOLO and TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2007 the Stone Age, CANADA, New York, NY Project: Rendition, Momenta Art, Brooklyn, NY

CARRIE MOYER [email protected] SOLO AND TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2007 The Stone Age, CANADA, New York, NY Project: Rendition, Momenta Art, Brooklyn, NY. Collaboration by JC2: Joy Episalla, Joy Garnett, Carrie Moyer, and Carrie Yamaoka Black Gold, rowlandcontemporary, Chicago, IL Black Gold, Hunt Gallery, Mary Baldwin College, Staunton, VA 2006 Carrie Moyer and Diana Puntar, Samson Projects, Boston, MA 2004 Two Women: Carrie Moyer and Sheila Pepe, Palm Beach ICA, Palm Beach, FL (catalog) Sister Resister, Diverseworks, Houston, TX Façade Project, Triple Candie, New York, NY 2003 Chromafesto, CANADA, New York, NY 2002 Hail Comrade!, Debs & Co., New York, NY The Bard Paintings, Gallery @ Green Street, Boston, MA Meat Cloud, Debs & Co., New York, NY Straight to Hell: 10 Years of Dyke Action Machine! Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, CA; Diverseworks, Houston, TX (traveling exhibition with catalog) 2000 God’s Army, Debs & Co., New York, NY GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2007 Don’t Let the Boys Win: Kinke Kooi, Carrie Moyer, and Lara Schnitger, Mills College Art Museum, Oakland, CA Late Liberties, John Connelly Presents, New York, NY. Curator: Augusto Abrizo Shared Women, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), Los Angeles, CA. Curators: Eve Fowler, Emily Roysdon, A.L. Steiner Beauty Is In the Streets, Mason Gross School of the Arts Galleries, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ Affinities: Painting in Abstraction, CCS Galleries, Hessel Museum, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY. Curator: Kate McNamara Absolute Abstraction, Judy Ann Goldman Fine Arts, Boston, MA Hot and Cold: Abstract Prints from the Center Street Studio, Trustman Art Gallery, Simmons College, Boston, MA New Prints/Spring 2007, IPCNY/International Print Center New York, New York, NY. -

Cartographic Perspectives Information Society 1

Number 53, Winterjournal 2006 of the Northcartographic American Cartographic perspectives Information Society 1 cartographic perspectives Number 53, Winter 2006 in this issue Letter from the Editor INTRODUCTION Art and Mapping: An Introduction 4 Denis Cosgrove Dear Members of NACIS, FEATURED ARTICLES Welcome to CP53, the first issue of Map Art 5 Cartographic Perspectives in 2006. I Denis Wood plan to be brief with my column as there is plenty to read on the fol- Interpreting Map Art with a Perspective Learned from 15 lowing pages. This is an important J.M. Blaut issue on Art and Cartography that Dalia Varanka was spearheaded about a year ago by Denis Wood and John Krygier. Art-Machines, Body-Ovens and Map-Recipes: Entries for a 24 It’s importance lies in the fact that Psychogeographic Dictionary nothing like this has ever been kanarinka published in an academic journal. Ever. To punctuate it’s importance, Jake Barton’s Performance Maps: An Essay 41 let me share a view of one of the John Krygier reviewers of this volume: CARTOGRAPHIC TECHNIQUES …publish these articles. Nothing Cartographic Design on Maine’s Appalachian Trail 51 more, nothing less. Publish them. Michael Hermann and Eugene Carpentier III They are exciting. They are interest- ing: they stimulate thought! …They CARTOGRAPHIC COLLECTIONS are the first essays I’ve read (other Illinois Historical Aerial Photography Digital Archive Keeps 56 than exhibition catalogs) that actu- Growing ally try — and succeed — to come to Arlyn Booth and Tom Huber terms with the intersections of maps and art, that replace the old formula REVIEWS of maps in/as art, art in/as maps by Historical Atlas of Central America 58 Reviewed by Mary L. -

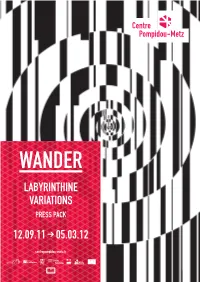

Labyrinthine Variations 12.09.11 → 05.03.12

WANDER LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS PRESS PACK 12.09.11 > 05.03.12 centrepompidou-metz.fr PRESS PACK - WANDER, LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION .................................................... 02 2. THE EXHIBITION E I TH LAByRINTH AS ARCHITECTURE ....................................................................... 03 II SpACE / TImE .......................................................................................................... 03 III THE mENTAL LAByRINTH ........................................................................................ 04 IV mETROpOLIS .......................................................................................................... 05 V KINETIC DISLOCATION ............................................................................................ 06 VI CApTIVE .................................................................................................................. 07 VII INITIATION / ENLIgHTENmENT ................................................................................ 08 VIII ART AS LAByRINTH ................................................................................................ 09 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ..................................................................... 10 4. LINEAgES, LAByRINTHINE DETOURS - WORKS, HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOgICAL ARTEFACTS .................... 12 5.Om C m ISSIONED WORKS ............................................................................. 13 6. EXHIBITION DESIgN ....................................................................................... -

Downloading of Movies, Television Shows and Other Video Programming, Some of Which Charge a Nominal Or No Fee for Access

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2011 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO Commission file number 001-32871 COMCAST CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) PENNSYLVANIA 27-0000798 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) One Comcast Center, Philadelphia, PA 19103-2838 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (215) 286-1700 SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OF THE ACT: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on which Registered Class A Common Stock, $0.01 par value NASDAQ Global Select Market Class A Special Common Stock, $0.01 par value NASDAQ Global Select Market 2.0% Exchangeable Subordinated Debentures due 2029 New York Stock Exchange 5.50% Notes due 2029 New York Stock Exchange 6.625% Notes due 2056 New York Stock Exchange 7.00% Notes due 2055 New York Stock Exchange 8.375% Guaranteed Notes due 2013 New York Stock Exchange 9.455% Guaranteed Notes due 2022 New York Stock Exchange SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(g) OF THE ACT: NONE Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. -

SHIRCORE Jenny

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd JENNY SHIRCORE - Make-Up and Hair Designer 2003 Women in Film Award for Best Technical Achievement Member of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences THE DIG Director: Simon Stone. Producers: Murray Ferguson, Gabrielle Tana and Ellie Wood. Starring: Lily James, Ralph Fiennes and Carey Mulligan. BBC Films. BAFTA Nomination 2021 - Best Make-Up & Hair KINGSMAN: THE GREAT GAME Director: Matthew Vaughn. Producer: Matthew Vaughn. Starring: Ralph Fiennes and Tom Holland. Marv Films / Twentieth Century Fox. THE AERONAUTS Director: Tom Harper. Producers: Tom Harper, David Hoberman and Todd Lieberman. Starring: Felicity Jones and Eddie Redmayne. Amazon Studios. MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS Director: Josie Rourke. Producers: Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner and Debra Hayward. Starring: Margot Robbie, Saoirse Ronan and Joe Alwyn. Focus Features / Working Title Films. Academy Award Nomination 2019 - Best Make-Up & Hairstyling BAFTA Nomination 2019 - Best Make-Up & Hair THE NUTCRACKER & THE FOUR REALMS Director: Lasse Hallström. Producers: Mark Gordon, Larry J. Franco and Lindy Goldstein. Starring: Keira Knightley, Morgan Freeman, Helen Mirren and Misty Copeland. The Walt Disney Studios / The Mark Gordon Company. WILL Director: Shekhar Kapur. Exec. Producers: Alison Owen and Debra Hayward. Starring: Laurie Davidson, Colm Meaney and Mattias Inwood. TNT / Ninth Floor UK Productions. Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 JENNY SHIRCORE Contd … 2 BEAUTY & THE BEAST Director: Bill Condon. Producers: Don Hahn, David Hoberman and Todd Lieberman. Starring: Emma Watson, Dan Stevens, Emma Thompson and Ian McKellen. Disney / Mandeville Films. -

Artists, Critics, Curators Speaker Series

Nasher Sculpture Center Announces Spring 2016 Line-up for 360: Artists, Critics, Curators Speaker Series Monthly speaker series explores topics of modern and contemporary art and design DALLAS, Texas (January 19, 2016) – The Nasher Sculpture Center is pleased to announce the line-up for the spring 2016 season of the Nasher speaker series, 360: Artists, Critics, Curators, which features conversations and lectures on the ever-expanding definition of sculpture and the thinking behind some of the world’s most innovative artwork, architecture, and design. The public is invited to join us for fresh understanding, insights and inspiring ideas. Lectures are free with museum admission: $10 for adults, $7 for seniors, $5 for students, and free for Members. Seating is limited, so reservations are requested. Immediately following the presentation, guests will enjoy a wine reception with RSVP. For information and reservations, email [email protected] or call 214.242.5159. Updates and information are available at www.NasherSculptureCenter.org/360. Monthly Lectures: Ann Veronica Janssens, Exhibition Artist Saturday, January 23, 11:30 am Known primarily as a light artist, Ann Veronica Janssens is interested in “situations of dazzlement… the persistence of vision, vertigo, saturation, speed, and exhaustion”—in other words, how the body responds to certain scientific phenomena and conditions put upon it. Janssens will speak on the opening day of her self-titled exhibition at the Nasher, the first one-person museum show in the United States for the Brussels-based artist. For the exhibition, she will install several sculptural works that allow viewers to encounter shifts in surface, depth, and color, challenging perception and destabilizing their sense of sight and space. -

Gretchen Bender

GRETCHEN BENDER Born 1951, Seaford, Delaware Died 2004 EDUCATION 1973 BFA University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill SELECTED ONE-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2019 So Much Deathless, Red Bull Arts, New York 2017 Living With Pain, Wilkinson Gallery, London 2015 Tate Liverpool; Project Arts Centre, Dublin Total Recall, Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin 2013 Tracking the Thrill, The Kitchen, New York Bunker 259, New York 2012 Tracking the Thrill, The Poor Farm, Little Wolf, Wisconsin 1991 Gretchen Bender: Work 1981-1991, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York; traveled to Alberta College of Art, Calgary; Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art 1990 Donnell Library, New York Dana Arts Center, Colgate University, Hamilton, New York 1989 Meyers/Bloom, Los Angeles Galerie Bebert, Rotterdam 1988 Metro Pictures, New York Museum of Fine Arts, Houston 1987 Total Recall, The Kitchen, New York; Moderna Museet, Stockholm 1986 Nature Morte, New York 1985 Nature Morte, New York 1984 CEPA Gallery, Buffalo 1983 Nature Morte, New York 1982 Change Your Art, Nature Morte, New York SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2020 Bizarre Silks, Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts, etc., Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland Glasgow International 2019 Collection 1970s—Present, Museum of Modern Art, New York (Dumping Core; on view through Spring 2021) 2018 Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston; traveled to University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor Expired Attachment, Mx Gallery, New York Art in Motion. 100 Masterpieces with and through Media.