The Central Rhodopes Region in the Roman Road System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Espaço E Economia, 10 | 2017 Alternative Tourism in Bulgaria – General Characteristics 2

Espaço e Economia Revista brasileira de geografia econômica 10 | 2017 Ano V, número 10 Alternative tourism in Bulgaria – general characteristics Turismo alternativo na Bulgária – características gerais Le tourisme alternatif en Bulgarie : traits générales Turismo alternativo en Bulgaria: características generales. Milen Penerliev Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/espacoeconomia/2921 DOI: 10.4000/espacoeconomia.2921 ISSN: 2317-7837 Publisher Núcleo de Pesquisa Espaço & Economia Electronic reference Milen Penerliev, « Alternative tourism in Bulgaria – general characteristics », Espaço e Economia [Online], 10 | 2017, Online since 17 July 2017, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/espacoeconomia/2921 ; DOI : 10.4000/espacoeconomia.2921 This text was automatically generated on 19 April 2019. © NuPEE Alternative tourism in Bulgaria – general characteristics 1 Alternative tourism in Bulgaria – general characteristics Turismo alternativo na Bulgária – características gerais Le tourisme alternatif en Bulgarie : traits générales Turismo alternativo en Bulgaria: características generales. Milen Penerliev 1 Alternative tourism is a form of tourism which represents an alternative to the conventional mass tourism. Its forms are small-scale, low-density, divided into forms practiced in urban (religious, cultural, business) and rural areas. Alternative tourism is an attempt to preserve, protect and improve the quality of the existing resource base, which is fundamental for tourism itself. Alternative tourism is featured by active encouragement and care for the development of additional andspecific attractions as well the infrastructure, which are based on the local resources, while at the same time aiding the latter. It has an impact on the quality of life in the region, improves the infrastructure and increases the educational and cultural level of the local community. -

ARTICULATA 2009 24 (1/2): 79–108 FAUNISTIK New Records and a New

Deutschen Gesellschaft für Orthopterologie e.V.; download http://www.dgfo-articulata.de/ ARTICULATA 2009 24 (1/2): 79108 FAUNISTIK New records and a new synonym of Orthoptera from Bulgaria Dragan P. Chobanov Abstract After a revision of available Orthoptera collections in Bulgaria, 9 species with one subspecies are added and 15 species and one subspecies are omitted from the list of Bulgarian fauna. A supplement to the description and a diagnosis of Iso- phya pavelii Brunner von Wattenwyl (= Isophya rammei Peshev, syn.n.) is presented. Full reference and distributional data for Bulgaria are given for 31 taxa. Oscillograms and frequency spectra of the songs of Barbitistes constrictus, Isophya pavelii and I. rectipennis are presented. Zusammenfassung Im Rahmen einer Durchsicht der verfügbaren Orthopterensammlungen in Bzlgarien wurden in die Gesamtliste der bulgarischen Fauna insgesamt neun Arten und eine Unterart neu aufgenommen sowie 15 Arten und eine Unterart von der Liste gestrichen. In der vorleigenden Arbeit werden von 31 Taxa die Refe- renz- und Verbreitungsdaten aus Bulgarien aufgelistet. Für Isophya pavelii Brun- ner von Wattenwyl (= Isophya rammei Peshev, syn.n.) erfolgt eine Ergänzung der Artbeschreibung und Differenzialdiagnose. Die Stridulationen von Barbitistes constrictus, Isophya pavelii und Isophya rectipennis werden als Frequenzspek- tren und Oszillogramme dargestellt. Introduction After a nearly 20-years break in the active studies on Orthoptera of Bulgaria, in the last years few works were published (POPOV et al. 2001, CHOBANOV 2003, ANDREEVA 2003, HELLER &LEHMANN 2004, POPOV &CHOBANOV 2004, POPOV 2007, ÇIPLAK et al. 2007) adding new faunistic and taxonomic data on the order in this country. POPOV (2007), incorporating all the published information on Or- thoptera from Bulgaria up to date, including some unpublished data, counted 239 taxa for the country (221 species and 18 subspecies). -

Bulgaria Eco Tours and Village Life

BULGARIA ECO TOURS AND VILLAGE LIFE www.bulgariatravel.org Unique facts about Bulgaria INTRODUCTION To get to know Bulgaria, one has to dive into its authenticity, to taste the product of its nature, to backpack across the country and to gather bouquets of memories and impressions. The variety of The treasure of Bulgarian nature is well preserved Bulgarian nature offers abundant opportunities for engaging outdoor in the national conservation parks. The climate and activities – one can hike around the many eco trails in the National diverse landscape across the country are combined Parks and preservation areas, observe rare animal and bird species or in a unique way. This is one of the many reasons for visit caves and landmarks. the country to have such an animal and plant diversity. Bulgaria has a dense net of eco trails. There are new routes constantly Many rare, endangered and endemic species live in the marked across the mountains, which makes many places of interest Bulgarian conservation parks. Through the territory and landmarks more accessible. of the country passes Via Pontica – the route of the migratory birds from Europe to Africa. The eco-friendly outdoor activities are easily combined with the opportunity to enjoy rural and alternative tours. One can get acquainted with the authentic Bulgarian folklore and can stay in a traditional vintage village house in the regions of Rila, Pirin, The Rodopi For those who love nature, Bulgaria is the Mountains, Strandzha, Stara Planina (the Balkan Range), the Upper place to be. You can appreciate the full Thracian valley, the Danube and the Black Sea Coast regions. -

Turystyka Eko I Wiejska

BUŁGARIA Turystyka eko i wiejska www .bulgariatravel.or g Kilka unikalnych faktów o Bułgarii WSTĘP Aby zapoznać się z Bułgarią, musicie zatopić się w jej autentyczności, posmakować owoców jej przyrody, obejść z plecakiem aby zebrać bukiet wspomnień i uczuć. Różnorodność bułgarskiej przyrody jest Bogactwo bułgarskiej natury jest starannie chronione świetnym warunkiem ku pomyślnemu rozwojowi ekoturystyki – spacery w narodowych parkach przyrodniczych i rezerwatach. w parkach narodowych i rezerwatach po jednej z wielu szlaków eko, Specyficzny klimat i różnorodność rzeźby terenu w kraju obserwowanie ptaków i zwierząt, odwiedziny jaskiń i zabytków i są połączone w wyjątkowy sposób oraz są przyczyną przyrody. wyjątkowo bogatej roślinności i gatunków zwierząt. Bardzo rzadkie gatunki pod ochroną i endemiczne Gęsta sieć szlaków eko obejmuje całą Bułgarię. W kraju nieprzerwalnie zamieszkują bułgarskie rezerwaty. W granicach kraju są znakowane nowe szlaki, które dają dostęp do jeszcze większej liczby przechodzi Via Pontica – szlak przelotów ptaków z zabytków i innych interesujących miejsc. Europy do Afryki. Przyjazne dla środowiska działania turystyczne cudownie komponują się z możliwościami trenowania turystyki wiejskiej i alternatywnejPrzyjazne dla środowiska działania turystyczne cudownie komponują się z możliwościami trenowania turystyki wiejskiej i alternatywnej. Zapoznanie się z autentycznym W Bułgarii miłośnicy przyrody mogą cieszyć bułgarskim folklorem, jak i zakwaterowanie w starych wiejskich domach są się pełnym jej bogactwem dzięki szerokiej możliwe w regionie Riło-Piryńskim, Rodopskim, Strandżańskim, siatce eko szlaków. Przeprowadzają one Staropłanińskim, Trackim, Dunajskim i Czarnomorskim. Wiele wsi już swoich gości przez piękne miejsca i dają przyjmuje gości, a gospodarze organizują różnorodne wydarzenia – jazdy dostęp do wyjątkowych miejsc i zabytków konne, zapoznanie z miejscowym rzemiosłem, spacery do zabytków przyrody. Szlaki są różnorodne pod względem przyrody, wieczory folklorystyczne i rozrywki wśród przyrody. -

Rural Tourism Development, a Prerequisite for the Preservation of Bulgarian Traditions

1 www.esa-conference.ru Rural tourism development, a prerequisite for the preservation of Bulgarian traditions Teodora Rizova, Chief Assist. Ph. D in Social Sciences New Bulgarian University (Sofia, Bulgaria) The village is the place where agricultural production and related employment hold the most weight. It is the cradle of authentic traditions and cultural practices – they are “reserved” for preserving the experience of cultural, linguistic, and, in general – national identity. The village is not a mass tourist destination. It is an alternative to mass tourism and a place, as well as an environ- ment suitable for different forms of specialized tourism – ecological, mountain, adventure, theme tourism, related to cultural-historical heritage, religion, wine, traditions and local cuisine, ethnography, traditional music and crafts (Art. 28 of the Statute of BAAT). In agricultural and social policy of the European Union rural tourism is seen as a form of diversification of activi- ties and increase farmers' incomes. Keywords: rural tourism, traditions, cultural - historical heritage, traditional music and crafts. The work hereby aims to reveal the perspectives available respective region, while indulging the calmness and infor- to preserve the Bulgarian lifestyle and traditions, through the mality of relationships [1]. development of rural tourism and other alternative forms of The rural tourism in Bulgaria is starting to gain popular- tourism. ity not only among Bulgarians, but also among international tourists. More and more foreign visitors combine the holiday Bulgaria is a country with rich biodiversity – over 3,750 in one of our big, famous resorts with a visit to a Bulgarian varieties of higher plants, of which 763 are listed in the Red village. -

Bacillus Bulgaricus' : the Breeding of National Pride

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kingston University Research Repository This is not the Version of Record. For more information on Nancheva, Nevena (2019) 'Bacillus Bulgaricus' : the breeding of national pride. In: Ichijo, Atsuko , Johannes, Venetia and Ranta, Ronald, (eds.) The The emergence of national food : the dynamics of food and nationalism. London, U.K. : Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 61-72. see https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/the-emergence-of-national-food-9781350074132/ Chapter Bacillus Bulgaricus: The Breeding of National Pride Nevena Nancheva, Kingston University London This chapter is a case study of Bulgarian food nationalism with a focus on yogurt (kiselo mlyako), exploring the nationalisation of a staple food which has been produced and consumed in and around the Balkan region for centuries. The chapter references the social construction of yoghurt as a uniquely Bulgarian product, from the 1905 study that discovered the particular subspecies of the lactic acid producing bacteria carrying the national reference (bulgaricus), to the patenting of the product under the Bulgarian National Standard (BDS) since 1971 and its nationally controlled exports. The aim of the chapter is to explore the process of this nationalization, demonstrating that the Bulgarisation of yoghurt is linked to specific economic, political and cultural agendas whose pursuit is impossible unless yoghurt is seen as ethno-nationally authentic. The interrogation of yoghurt's Bulgarian-ness in this chapter engages with the mythical construction of yoghurt as an inherently national product challenging the most prominent ethno-national myths sustaining it: the myth of yoghurt as quintessentially Bulgarian food staple, the myth of yoghurt as ethno-nationally specific to Bulgarian producers, and the myth of yoghurt as representative of Bulgarian-ness and Bulgarian authenticity abroad. -

New Data on the Butterflies of Western Stara Planina Mts (Bulgaria & Serbia) (Lepidoptera, Papilionoidea)

Ecologica Montenegrina 20: 119-162 (2019) This journal is available online at: www.biotaxa.org/em New data on the butterflies of Western Stara Planina Mts (Bulgaria & Serbia) (Lepidoptera, Papilionoidea) MARIO LANGOUROV National Museum of Natural History, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 1 Tsar Osvoboditel Blvd, 1000 Sofia, Bulgaria. E-mail: [email protected] Received 9 January 2019 │ Accepted by V. Pešić: 7 March 2019 │ Published online 9 March 2019. Abstract The paper represents results of surveys carried out in the Western Stara Planina Mts within the last four years in order to improve the knowledge of the butterfly fauna, especially in the Bulgarian part of the mountain. A total of 150 species of Lepidoptera (Papilionoidea) was recorded with comments on their distribution in the Bulgarian part of the studied region. Nineteen species were recorded for the first time in the Bulgarian part of the mountain and one species (Apatura metis) – for the Serbian part. It has been found that the highest butterfly diversity is linked to the largest limestone area in the mountain near Komshtitsa Village where 101 species were observed. Interesting records for some rare or endangered species (Muschampia cribrellum, M. tessellum, Lycaena helle, Kirinia climene, Apatura metis, Nymphalis vaualbum, Melitaea didyma, M. arduinna, M. diamina and Brenthis ino) are discussed in detail. The high conservation value of the studied region proves by the species considered as threatened at the European level, of which seven species are included in the Annexes II and IV of the Habitats Directive, 12 species are listed in the Red Data Book of European butterflies and 26 in the European Red List of Butterflies. -

Preservation of Local Grain Legume Species for Food in Bulgaria

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 72 (2017) 26-33 EISSN 2392-2192 Preservation of local grain legume species for food in Bulgaria Siyka Angelova & Mariya Sabeva Institute of Plant Genetic Resources ”K. Malkov”, 4122 Sadovo, Bulgaria E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT In connection with IPGR participation in various national and international projects during the recent years, investigations have been conducted, in order to create a database of available old plant materials of grain legumes of Bulgarian origin. Different areas throughout Bulgaria with diverse relief, soil and climatic conditions have been visited. From the literature review and collected from previous studies data we identified the specific areas these crops occupy traditionally in the home garden and are sentimentally linked to family traditions. Questionnaires were developed, which intended to complement and update the existing information about location, farmer’s name, number cultivated species, usage, cooking recipes and storage. In this respect, numerous interviews with local people were conducted and were visited community centers, museums, schools and other organizations and institutions. Keywords: Grain legume, local varieties, utilization, variability 1. INTRODUCTION Large set of grain legumes have traditionally been grown in our country (2,3). The National Gene Bank of Bulgaria stores about 9000 specimens of this group. The collections are presented by 10 botanical geniuses and contain diverse plant material. The structure of various collection types includes old varieties and populations; selection lines - donors; mutant forms; wild species; newly selected varieties and commercial ones of Bulgarian origin, Europe and all the world (2-4,12). World Scientific News 72 (2017) 26-33 During the recent years, the efforts of our researchers have been focused on collecting and storage of all materials from native origin, which are supported and used at the Institute for Plant Genetic Resources (IPGR) in Sadovo, Bulgaria (9,12,15). -

Guide to Western Stara Planina the Unknown Natural Wealth Authors: Lora Zhebril Zhivko Momchev

WORKING TOGETHER IN SUPPORT OF SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS GUIDE BG GUIDE TO WESTERN STARA PLANINA THE UNKNOWN NATURAL WEALTH AUTHORS: LORA ZHEBRIL ZHIVKO MOMCHEV EDITOR: VENCI GRADINAROV WWW.BGTEXT.BG GRAPHIC DESIGN: OILARIPI TREKKING ASSOCIATION WWW.OILARIPI.COM FRONT COVER: IVAN VELOV PUBLISHED BY WWF BULGARIA, SOFIA © 2017 WWF BULGARIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ALL MATERIALS IN THIS PUBLICATION ARE SUBJECT TO COPYRIGHT AND CAN BE REPRO- DUCED WITH PERMISSION. ANY REPRODUCTION IN FULL OR IN PART MUST MENTION THE TI- TLE AND CREDIT THE ABOVE-MENTIONED PUBLISHER (WWF BULGARIA) AS THE COPYRIGHT OWNER. THE DESIGNATION OF GEOGRAPHICAL ENTITIES IN THIS REPORT, AND THE PRE- SENTATION OF MATERIAL, DO NOT IMPLY THE EXPRESSION OF ANY OPINION WHATSOEVER ON THE PART OF WWF CONCERNING THE LEGAL STATUS OF ANY COUNTRY, TERRITORY, OR AREA, OR OF ITS AUTHORITIES, OR CONCERNING THE DELIMITATION OF ITS FRONTIERS OR BOUNDARIES. GUIDE TO WESTERN STARA PLANINA THE UNKNOWN NATURAL WEALTH © PLAMEN DIMITROV PLAMEN © THE GUIDEBOOK FOR WESTERN STARA PLANINA WAS DEVELOPED WITHIN THE “FOR THE BALKAN AND THE PEOPLE”PROJECT, AN INITIATIVE OF SIX BULGARIAN AND FOUR SWISS ORGANIZATIONS. IT WILL GIVE YOU A HINT ABOUT SOME REMARKABLE PLACES TO VISIT IN THE AREA AND IT WILL INTRODUCE YOU TO SOME OF THE SIGNIFICANT SUCCESSFUL RESULTS OF THE PROJECT OVER THE PAST FIVE YEARS. IT WILL TELL YOU HOW THE IMPOSSIBLE SOMETIMES BECOMES POSSIBLE AT PLACES WHERE NOBODY EXPECTED. WITH THE HELP OF THE FINANCIAL SUPPORT OF THE BULGARIAN-SWISS COOPERATION PROGRAM AND THE EFFORTS OF ALL THE EXPERTS FROM THE PARTNER ORGANIZATIONS, SEVERAL FARMERS FROM NORTH-WEST BULGARIA MANAGED TO SUCCESSFULLY COM- PLETE ALL PROCEDURES FOR REGISTRATION AS PRODUCERS , COMPLETELY OUT OF THE GREY SECTOR. -

Historia Naturalis Bulgarica

QH178 .9 58 V. 10 1999 HISTORIA NATURALIS BULGARICA & 10 fflSTORIA NATURALIS BULGARICA Volume 10, Sofia, 1999 Bulgarian Academy of Sciences - National Museum of Natural History cm.H.c. ) (cm.H.c. () cm.H.c. cm.H.c. cm.H.c. - . ^1 1000 © - ,^1999 EDITORIAL BOARD U Petar BERON (Editor-in-CMef) cm.H.c. : Alexi POPOV (Secretary) Krassimir KUMANSKI Stoitse ANDREEV 31.12.1999 Zlatozar BOEV 70x100/16 350 Address 10.25 National Museum of Natureil History 6 „" 1, Tsar Osvoboditel Blvd 1000 Sofia ISSN 0205-3640 Historia naturalis bulgarica 10, , 1999 - 60 (.) 6 - 6 (., . .) 13 - (Insecta: Heteroptera) 6 (., pes. .) 35 - - (Coleoptera: Carabidae) .-HI (., . .) 67 - Egira tibori Hreblay, 1994 - (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae: Hadeninae) (., . .) 77 - Tetrao partium (Kretzoi, 1962) (Aves: Tetraonidae) (., . .) 85 - (Aves: Otitidae) (., . .) 97 - Regulus bulgaricus sp. - (Aves: Sylviidae) (., . .) 109 , - ,Pogonu (., . .) 117 , - „ - " (., pes. .) 125 , , , - 1 6 pes. (., .) 133 - (., pes. .) 147 - gecem (.) ^ 34 - (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) (.) 84 - 60 - , 116 (.) , - ,- 124 (1967 1994) (.) - (.) 132 CONTENTS Alexi POPOV - KraSsimir Kumanski at sixty years of age (In Bulgarian) Scientific publications Petar BERON - Biodiversity of the high mountain terrestrial fauna in Bxilgaria (In English, summary in Bulgarian) 13 Michail JOSIFOV - Heteropterous insects in the SandansM-Petrich Kettle, Southwestern Bulgaria (In English, simimary in Bulgeirian) 35 Borislav GUEORGUIEV - Contribution to the study of the ground-beetle fauna (Coleoptera: Carabidae) of the Osogovo -

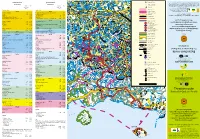

THRACIAN ROUTE Byzantium Route Be Cannot It Circumstances No at and Smolyan of Municipality the from Carried Is Map the of Content The

Regional Center Member”. Negotiated the and Union European the of position official the reflect map this that consider THRACIAN ROUTE Byzantium Route be cannot it circumstances no at and Smolyan of Municipality the from carried is map the of content the by the European Union through the European Fund for Regional Development. The whole responsibility for for responsibility whole The Development. Regional for Fund European the through Union European the by Hour Distribution Hour Distribution co-funded 2007-2013, Greece-Bulgaria cooperation territorial European for Programme the of aid financial Municipal Center the with implementing is which THRABYZHE, ACRONYM: Coast”. Sea Aegean Northern the and Mountains Distance Time Distance Time Rhodopi the in Heritage Cultural Byzantine and “Thracian 7949 project the within created is map “This (with accumu- (with accumu- City Hall Shishkov” “Stoyu tory - lation) lation)Septemvri his of museum Regional - partner Bulgarian Belovo State border Municipality Samothrace - partner Greece Arrival in Chepelare Arrival in Devin Pazardzhik Municipality Smolyan - partner Lead Day One Day One Regional border Chirpan Municipal border Departure from Chepelare 0 km 00:00 h The Byzantium and Bulgarian fortress “Devinsko Gradishte” 05:00 h 2013» - 2007 Bulgaria - Greece Zabardo 27 km 00:32 h The Natural Landmark “Canyon” 02:00 h Plovdiv Highway Cooperation Territorial European for «Programme the for Funding Ancient road 02:00 h Departure from Devin 0 km 00:00 h Project road Natural landmark “The Wonderful Bridges” -

Annexes to Rural Development Programme

ANNEXES TO RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (2007-2013) TABLE OF CONTENTS Annex 1 ...........................................................................................................................................4 Information on the Consultation Process ........................................................................................4 Annex 2 .........................................................................................................................................13 Organisations and Institutions Invited to the Monitoring Committee of the Implementation of the Rural Development Programme 2007-2013 .................................................................................13 Annex 3 .........................................................................................................................................16 Baseline, Output, Result and Impact Indicators............................................................................16 Annex 4 .........................................................................................................................................29 Annexes to the Axis 1 Measures...................................................................................................29 Attachment 1 (Measure 121 Modernisation of Agricultural Holding) .........................................30 List of Newly Introduced Community Standards .........................................................................30 Attachment 1.A. (Measure 121 Modernisation of Agricultural Holding